Hello Everyone,

Situated 330 miles north of the Arctic Circle, Barrow is the northernmost community in the United States. With a population of 4,500, 64% who are of Iñupiat Eskimos descent, it is one of the largest Alaskan settlements for that culture. A one day tour of this village allowed us to better understand this culture combining traditional ways with such elements of modern living as cell phones and the Internet.

GENERAL INFORMATION

The city of Barrow consists of three sections: south, central, and north. The southern section, Barrow, is the oldest and second largest district. Serving as downtown, it contains the airport, Wiley Post/Will Rogers Memorial, the area’s elementary and high schools, restaurants, hotels, the police station, city hall, a Wells Fargo bank, and several houses.

The central area, Browerville, is the largest district. It’s primarily residential but many businesses have moved there in recent years. In addition to homes, it includes the library, post office, middle school, hospital, two grocery stores, a hotel, and two restaurants. It also is home to the Iñupiat Heritage Center.

The north section is the most isolated. It contains Ilisagvik College, an accredited two-year college, whose location was formerly the Naval Arctic Research Lab.

Driving around Barrow, you see dirt roads. Buildings are on concrete footings or pylons in order to let buildings shift due to the permafrost layer on which they are situated. Earl toured Barrow in 1969 and did not see many differences this June. For him, the two major ones were that in 1969 lots of gas pipelines used for heating were above ground. These have now been buried. He saw many large shipping containers around town instead.

Barrow has long winters and long summers. The sun sets on November 18 or 19 and remains below the horizon for about 65 days. It rises again January 22 or 23. As it doesn’t set from the beginning of May until the first of August, Barrow receives more than 90 days of continuous daylight.

If you visit Barrow, you’ll need cold weather clothing since the village has the lowest average temperatures in Alaska. Temperatures remain below freezing from early October through late May. Low wind chills and “white out” conditions from blowing snow are very common. The high temperature is above freezing for only about 120 days. From June through September, highs average 35-47 and lows between 28 and 34. July is the warmest month. Freezing temperatures and snowfall can occur in any month of the year. It was in the 30's and overcast when we were there June 6.

A LITTLE HISTORY

Archeological sites in the area indicate the Iñupiats lived around Barrow as far back as 500 AD. Our tour of the area stopped at Birnirk National Historic Landmark, located two miles north of the airport. Barrow was traditionally called Ukpiaguik. It’s a series of 20 sod dwelling mounds from the Birnirk culture of around 800 AD. These mounds contain the sunken remains of house ruins and cache pits. They were formed over hundreds of years when new homes were constructed atop the ruins of these older structures.

While whales were their primary source of food, they also fished and hunted seals, birds, caribou, and small land mammals.

We learned that the Birnirk tradition was the earliest instance of the current Iñupiat culture in northern Alaska. It lasted from 500 AD to 900 AD. The first archeological exploration was done by a Canadian, Stefansson Vihajalmer, in 1912, Later expeditions occurred in the 1930s and 1950s by Harvard University researchers.

The population at this site was small with only two or three houses lived in during a single occupation. Sod covered their roofs while driftwood and whale bones comprised the walls and roof frames. Thick earthen walls held in the heat from whale lamps. Entryways were sunken tunnels engineered to keep cold air from entering the interior.

Archeologists found artifacts used in home life, hunting, fishing, and travel. A major find was the discovery of the remains of a 1,000-year-old-boat called an umiak. Some of its parts still had decorative ivory inlays and baleen lashing. Other items included various tools, harpoon parts, toboggans, stone lamps for light and heat, and fragments of ceramic containers.

John Barrow of the British Royal Navy discovered Point Barrow when he explored and mapped North America’s Arctic coastline in 1825. It took until the 1850s for European commercial whaling ships to arrive at Barrow and for trade to start between them and the Iñupiats. The whalers brought firearms, ammunition, and alcohol in exchange for furs, ivory, and baleen. In 1884, Barrow’s first shore-based commercial whaling operation was established. Soon afterwards, whalers started coming from the East Coast of the United States,

In 1886, Charles D. Brower became the area’s first white settler. He and his partner opened their own whaling station in 1889 and the Cape Smythe Whaling and Trading Station, Barrow’s first store, in 1893. These and Brower’s home are seen in Barrow today.

The Iñupiat life changed with trade and commerce. Commercial whalers and traders brought western goods but also diseases. This caused the Eskimos to decline in population until Presbyterian mission doctors introduced western medical care. A Presbyterian Church, which we passed on our tour, was built in 1899. The first hospital opened in 1920.

In the last 50 to 100 years, Barrow has undergone major changes. Barrow was incorporated in 1958. Since the North Slope became home to the Arctic’s largest oil reserve, the oil and gas industry has brought new jobs. In 1972, the North Slope Borough was established. It added government and private jobs as well as created roads, water and electrical services, and health and education services for the area.

WILL ROGERS/WILEY POST MEMORIAL

Another stop Barrow tours make is at the memorial dedicated to Will Rogers and Wiley Post on August 15, 1982. It’s located near the Wiley Post-Will Rogers Memorial Airport. At the site is a sign showing the distances from Barrow to such places as Paris and Los Angeles.

While en route to Barrow, on August 15, 1935, Post and Rogers made an unplanned stop at Walakpa Bay, 16 miles south of Barrow. When they resumed their trip, their engine sputtered while taking off from a small tundra lake. Both men were killed when the plane struck the water and flipped. The cause is still unknown.

Will Rogers grew up on an Oklahoma ranch as the son of a Cherokee who had fought for the Confederacy. He started on the vaudeville circuit as a trick roper. By the 1920s, he was known for his roles in silent films. In 1922, he started writing syndicated columns for the New York Times. His comments on Americans and their place in the world led to his fame as a humorist. At the time of his death, he was at the height of his popularity as an actor in talkies.

Wiley Post, a fellow Oklahoman, grew up on a farmstead. After an Army stint in World War I, he worked as a roughneck in the Oklahoma oil fields and was arrested for armed robbery. He lost his left eye in an accident at an oil rig, but the payout from his injury provided funds that allowed him to learn to fly and acquire his own airplane. In the mid 1920s, he entered aviation as a parachutist for a flying circus.

Post broke the around-the-world record, of a little less than nine days, in 1931. He later smashed his record by nearly a day in 1933. Working with the Goodrich Company, he developed the first successful forerunner to the modern space suit. This allowed him to do an extensive amount of high altitude flying for which he gained tremendous respect in the aviation field. He won 30-35 top awards for his aviation conquests dealing with time, distance, and altitude.

Rogers and Post became friends in 1931 after Post’s around-the-world-flight. Rogers frequently mentioned Post in his newspaper column. In 1935, Post suggested a flying getaway to Rogers, who jumped at the opportunity. They had set off to explore Alaska and Russia when the accident occurred.

WHO ARE THE ESKIMOS

The Iñupiat Eskimos have always been a hunter and gatherer society living off the region’s sea and land resources. The whale, caribou, and seal have been three major sources of subsistence. The skills needed to hunt these animals have been passed down from generation to generation by the elders.

During late March, the Iñupiats establish tent camps at the edge of the ice, watching for whales from high points on land. The watch is maintained 24 hours a day. Whales pass Point Barrow in April and May on their way to their summer feeding grounds. They return south in late September and early October when this culture conducts a fall hunt. Hunts last as long as whales are in the vicinity. During unsuccessful seasons, seals, birds, and ducks have been sought instead.

When a whale is spotted, a crew of nine or ten people, led by a hunting captain, venture out in an open, sealskin-covered boat called an umiak. Up to five sealskins are used per boat depending on the vessel’s length. The skins last four years at the most. Then they turn black and start to rot.

The harpooner strikes the animal with a toggle-headed harpoon when a whale surfaces. Attached to the harpoon are two or three inflated sealskin floats made from the seals’ bladders. Each has a buoyancy of 200 to 500 pounds making it difficult for the animal to dive. A rawhide line connects the float to the harpoon. The rest of the crew cast floats, attached to the harpoon, quickly over the boat’s side. This marks where the whale is and slows it down from swimming away.

After it becomes exhausted, the animal is killed with a lance with a flint blade. The lancer severs the whale’s tendons controlling its flukes and then probes deeply into its vital organs. The crew retreats as the whale goes into a death flurry. It is then hauled to the beach where it is butchered. Dart guns with explosives and shoulder guns have replaced harpoons and lances in many cases. A number of umiak crews are needed to bring it ashore.

All available community members gather together to butcher the animal with each receiving meat and blubber. It is cut into lengths five to ten feet long and two feet wide.

Barrow has 45 captains, each responsible for their boat and crew. The village is allowed to catch 25 whales a year. Whaling feasts are held at the end of the season. A large celebration, Nalukataq, is held in June with feasts, dances, games, and the blanket toss. It is Barrow's number one attraction.

In 2016, our guide informed us that Barrow had harvested 12 whales and will hunt the rest in October. Meat is only for community consumption and is not allowed to be sold.

An attraction we saw at the coast was the Whale Bone Arch, a monument to the bowhead. This archway is made from a bowhead whale jaw from a creature caught in the 1950's. Sealskin boats surround the arch.

Caribou are usually hunted during the summer near the coast. Sometimes groups of hunters search inland for small migratory herds. In the past, they chased the animals into corrals where the men speared, snared, or shot them with bows and arrows.

During the spring and summer, attention also shifts to walruses and seals. Walruses

are pursued in a powerboat or umiak. Seals lay on top of the ice so are taken by stalking. Rifles have replaced harpoons whenever possible. Fishermen net salmon and whitefish in the rivers. Fish not eaten immediately are dried and stored or frozen in ice cellars to use during the winter. Other animals hunted are Dall sheep, ducks, and birds.

Summer has been the time of year to mine and stack veins of coal for winter fuel. Driftwood is gathered and stored if coal is not available. The Eskimos repair houses and store fresh water ice for later use in cooking and drinking. Storing meats for winter has remained vital.

Winter means the trapping season which concludes in mid March. Polar bear pelts are prized. Eskimos ice fish with lures of metal or ivory. Hunters wait patiently for seals to pop up at breathing holes then harpoon them. The seals are then pulled to the surface and killed.

Eskimos have always used all parts of the animals. They made clothing and obtained building materials from whales, walrus, and caribou. Meat was boiled or roasted. Caribou hides became their clothing, bedding, and tents while bones and antlers were used for tools and framework for shelters. Whale baleen was used to make baskets.

Hunting using traditional methods and tools occurs today for two reasons. Community activities revolve around the seasonal subsistence cycle, and the price for grocery store food, if available, is outrageous. One web site I saw had the prices from AC Value Store from December 2014. A dozen eggs cost $5.25. Eight ounces of Lay’s potato chips was $9.49. A pound of New York strip steak was $15.99.

Umiaks used for long distance travel are twice as large as hunting umiaks. Up to 40 people can travel in these boats which are about 30 feet long. Basket sleds are used for land travel while flat sleds are used for hauling large skin boats across the ice.

Traditional homes consisted of driftwood, sod, and dirt. They built them partly underground for warmth. Each village had at least one community house where men lived, worked, and held celebrations. At hunting and fishing sites, they lived in skin tents or driftwood lean-tos.

Despite portrayals in movies and magazines, igloos made of stacked ice and snow were never permanent dwellings. Though it’s possible that a northern hunter stranded in a blizzard might have built one as an emergency shelter. Today their houses resemble homes you’ll find in other Alaskan cities made with plywood, vinyl siding, glass windows, and painted in a variety of colors.

It was a tradition for the whole community to bring up the children. Parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles, and big brothers and sisters were involved. Toys provided their earliest education which children received as soon as they started to walk. These included balls made of caribou skin, small bows and arrows, dolls of skin and fur, and wood spinning tops. Later they learned by listening to stories, watching their elders, and practicing life skills on their own. They mastered the skills they needed to survive by the time they became teenagers.

HERITAGE CENTER

The Iñupiat Heritage Center is an affiliated area of New Bedford (Massachusetts) Whaling National Historical Park. Its museum recognizes the contributions of Iñupiats to whaling.

More than 2,000 whaling voyages from New Bedford sailed into the Arctic during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Commercial whaling became a major activity for many Alaskan natives, particularly the Iñupiats. They crewed on the ships, hunted for food for whalers, provided fur clothing, and sheltered many shipwrecked crews.

Another purpose is to promote and perpetuate Iñupiat history, language, and culture. In the 2-1/2 hours we were at the center, besides the museum, we spotted many artifacts and watched a dance performance. We also observed native Alaskans working on skin boats and creating art made of baleen and/or ivory. Their gift shop sells local crafts, jewelry, and clothing.

The dance program provides entertainment for visitors while allowing the Eskimos to tell their stories through different motions. Each dance has its own pattern. It’s a way to remember such personal life experiences as traveling and hunting. Drummers accompany the dancers throughout their performances.

Their dances covered such topics as welcome, working, a duck walk, traveling to the cabin, and a beautiful swan. Other themes were a little old man, playing with water, paddling various boats, and chopping firewood. At the end, the audience was invited to participate in two dances.

Next came a demonstration of the Eskimo yoyo. Its inner part is made from whale baleen while the outer part consists of caribou vertebrae. A whirling toy which created a giant humming sound followed. The program closed with the song “God will Take Care of You.”

The whaling museum covers all aspects of whaling from how hunting is prepared for and conducted by the community to whaling beliefs.

Iñupiats strongly believe in reincarnation and the recycling of spirits from one life to the next. Only if animal spirits are released can they return for future harvest. Whales are revered and respected by these people who thank it for giving its life to them. Hunters are taught that whales know when you have lived a good life and only give themselves to someone worthy of their sacrifice. After the hunt, the whale is treated with the utmost respect by men and women.

We spotted beautiful clothing such as a North Slope, handmade, floral print parka with wolverine fur for ruffs and a black one with wolf fur for ruffs. We also saw a parka made from ground squirrels and ones worn on special occasions.

This area also had boots. Men’s waterproof boots are worn when whaling or for summer hunting. These were made from hairless sealskin and bearded sealskin. Soles were sewed together with caribou sinew then saturated with seal oil to waterproof them.

Another section was on setting up camp. During traditional times, the whaling crew slept outdoors. Wives brought them food daily as it was a taboo to cook where the whale was caught. Today, they use tents with kerosene heaters. They cook, boil their meat, and make hot drinks at the site.

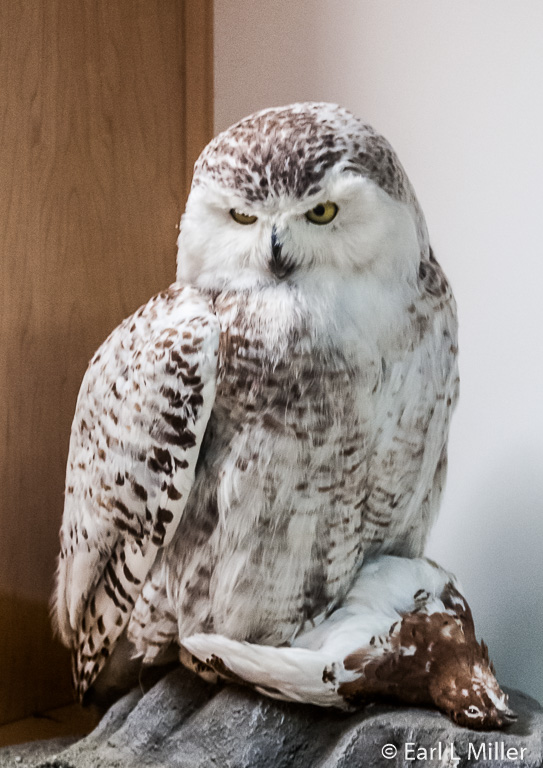

We saw a collection from the Ice Age including tusks from a wooly mammoth. Other artifacts included collections of face masks, moccasins, and migratory birds such as the snowy owl. In the lobby, we viewed a polar bear, more outfits, a 35-foot bowhead life-size whale, and a painting titled “Hunters of the North.”

OUR TOUR

Several companies offer tours to Barrow ranging from one to several days from mid May through mid September. Northern Alaska Tour Company out of Fairbanks was the booking office for our one day tour. They handled the airline arrangements with Alaska Airline and then coordinated with Top of the World Hotel’s Tundra Tour for our four-hour tour from noon to 4:00 p.m. in Barrow. Meals were not included nor were tips.

It is possible to book Top of the World and the airline on your own. However, if you do this check the airline prices first. Top of the World charges $150 for their portion. We discovered when we checked that the total price would have been higher than the $700 we paid per person. However, I have seen nonrefundable airline prices on line, if booked far in advance, that are much cheaper than $550.

When you book through Northern Alaska Tour Company, your entire payment is required at the time of your reservation. The company applies a $75 charge per person to any change made to the reservations once confirmed including name and date changes. A cancellation fee of $150 per person exists from 30 to 8 days out. Reservations are nonrefundable if cancelled within seven days prior to the tour date. Travel insurance is available.

We had originally planned to fly to Barrow from Fairbanks. However, the cost of the tour is $50 cheaper per person if you fly out of Anchorage. It is also more convenient as you have to fly to Anchorage from Barrow and catch a connecting flight to Fairbanks.

We flew in a 737 that stopped at Dead Horse, located at Prudhoe Bay. The plane was crowded with oil workers going to their job site. Our return flight was direct on a plane where half of the seating area had been converted into a cargo section. It, too, was packed with passengers.

Our guide and a van picked us up at the airport and took us to Top of the World Hotel where we had lunch in their restaurant. Then we loaded into a 25-passenger bus which took us to the Birnirk National Historic Landmark, Whale Arch, and the Wiley Post/Will Rogers Monument.

After our stop at the Iñupiat Heritage Center, we saw the university where former military Quonset buildings from World War II have been converted into classrooms and dormitories. It has 600 students. Driving around the campus, we saw a huge bowhead whale skull. They are up to 75 feet when full grown.

We stopped by the football stadium with its blue turf, then by the Air Force Barrow Radar site. A sign there indicated it was the location of the most northern totem pole in the world. Before returning to the Top of the World Hotel, we stopped by the beach at the Arctic Ocean. When the ice retreats from the shore, you can dip your hands in the ocean. On our visit, the ice was still there so we used the opportunity to walk on it instead.

Our final stop was at Barrow's version of Wal Mart, the Alaska Commercial Company. It's a place to buy everything from clothing to souvenirs and groceries.

Our group waited at the hotel for an hour-and-a-half until it was time to return to the airport. Passing through security was easy, and soon we were on our way back to Anchorage.

We found the tour interesting to learn about the Iñupiat culture. However, due to the high price and length of the tour, four hours, I would not do it a second time. We spent more time on our airline flights than seeing the Iñupiat Heritage Center and viewing the various sites.

Phone number for Northern Alaska Tour Company is (907) 474-8600 and for Tundra Tours at Top of the World Hotel it’s (907) 852-3900.

Situated 330 miles north of the Arctic Circle, Barrow is the northernmost community in the United States. With a population of 4,500, 64% who are of Iñupiat Eskimos descent, it is one of the largest Alaskan settlements for that culture. A one day tour of this village allowed us to better understand this culture combining traditional ways with such elements of modern living as cell phones and the Internet.

GENERAL INFORMATION

The city of Barrow consists of three sections: south, central, and north. The southern section, Barrow, is the oldest and second largest district. Serving as downtown, it contains the airport, Wiley Post/Will Rogers Memorial, the area’s elementary and high schools, restaurants, hotels, the police station, city hall, a Wells Fargo bank, and several houses.

The central area, Browerville, is the largest district. It’s primarily residential but many businesses have moved there in recent years. In addition to homes, it includes the library, post office, middle school, hospital, two grocery stores, a hotel, and two restaurants. It also is home to the Iñupiat Heritage Center.

The north section is the most isolated. It contains Ilisagvik College, an accredited two-year college, whose location was formerly the Naval Arctic Research Lab.

Driving around Barrow, you see dirt roads. Buildings are on concrete footings or pylons in order to let buildings shift due to the permafrost layer on which they are situated. Earl toured Barrow in 1969 and did not see many differences this June. For him, the two major ones were that in 1969 lots of gas pipelines used for heating were above ground. These have now been buried. He saw many large shipping containers around town instead.

Barrow has long winters and long summers. The sun sets on November 18 or 19 and remains below the horizon for about 65 days. It rises again January 22 or 23. As it doesn’t set from the beginning of May until the first of August, Barrow receives more than 90 days of continuous daylight.

If you visit Barrow, you’ll need cold weather clothing since the village has the lowest average temperatures in Alaska. Temperatures remain below freezing from early October through late May. Low wind chills and “white out” conditions from blowing snow are very common. The high temperature is above freezing for only about 120 days. From June through September, highs average 35-47 and lows between 28 and 34. July is the warmest month. Freezing temperatures and snowfall can occur in any month of the year. It was in the 30's and overcast when we were there June 6.

A LITTLE HISTORY

Archeological sites in the area indicate the Iñupiats lived around Barrow as far back as 500 AD. Our tour of the area stopped at Birnirk National Historic Landmark, located two miles north of the airport. Barrow was traditionally called Ukpiaguik. It’s a series of 20 sod dwelling mounds from the Birnirk culture of around 800 AD. These mounds contain the sunken remains of house ruins and cache pits. They were formed over hundreds of years when new homes were constructed atop the ruins of these older structures.

While whales were their primary source of food, they also fished and hunted seals, birds, caribou, and small land mammals.

We learned that the Birnirk tradition was the earliest instance of the current Iñupiat culture in northern Alaska. It lasted from 500 AD to 900 AD. The first archeological exploration was done by a Canadian, Stefansson Vihajalmer, in 1912, Later expeditions occurred in the 1930s and 1950s by Harvard University researchers.

The population at this site was small with only two or three houses lived in during a single occupation. Sod covered their roofs while driftwood and whale bones comprised the walls and roof frames. Thick earthen walls held in the heat from whale lamps. Entryways were sunken tunnels engineered to keep cold air from entering the interior.

Archeologists found artifacts used in home life, hunting, fishing, and travel. A major find was the discovery of the remains of a 1,000-year-old-boat called an umiak. Some of its parts still had decorative ivory inlays and baleen lashing. Other items included various tools, harpoon parts, toboggans, stone lamps for light and heat, and fragments of ceramic containers.

John Barrow of the British Royal Navy discovered Point Barrow when he explored and mapped North America’s Arctic coastline in 1825. It took until the 1850s for European commercial whaling ships to arrive at Barrow and for trade to start between them and the Iñupiats. The whalers brought firearms, ammunition, and alcohol in exchange for furs, ivory, and baleen. In 1884, Barrow’s first shore-based commercial whaling operation was established. Soon afterwards, whalers started coming from the East Coast of the United States,

In 1886, Charles D. Brower became the area’s first white settler. He and his partner opened their own whaling station in 1889 and the Cape Smythe Whaling and Trading Station, Barrow’s first store, in 1893. These and Brower’s home are seen in Barrow today.

The Iñupiat life changed with trade and commerce. Commercial whalers and traders brought western goods but also diseases. This caused the Eskimos to decline in population until Presbyterian mission doctors introduced western medical care. A Presbyterian Church, which we passed on our tour, was built in 1899. The first hospital opened in 1920.

In the last 50 to 100 years, Barrow has undergone major changes. Barrow was incorporated in 1958. Since the North Slope became home to the Arctic’s largest oil reserve, the oil and gas industry has brought new jobs. In 1972, the North Slope Borough was established. It added government and private jobs as well as created roads, water and electrical services, and health and education services for the area.

WILL ROGERS/WILEY POST MEMORIAL

Another stop Barrow tours make is at the memorial dedicated to Will Rogers and Wiley Post on August 15, 1982. It’s located near the Wiley Post-Will Rogers Memorial Airport. At the site is a sign showing the distances from Barrow to such places as Paris and Los Angeles.

While en route to Barrow, on August 15, 1935, Post and Rogers made an unplanned stop at Walakpa Bay, 16 miles south of Barrow. When they resumed their trip, their engine sputtered while taking off from a small tundra lake. Both men were killed when the plane struck the water and flipped. The cause is still unknown.

Will Rogers grew up on an Oklahoma ranch as the son of a Cherokee who had fought for the Confederacy. He started on the vaudeville circuit as a trick roper. By the 1920s, he was known for his roles in silent films. In 1922, he started writing syndicated columns for the New York Times. His comments on Americans and their place in the world led to his fame as a humorist. At the time of his death, he was at the height of his popularity as an actor in talkies.

Wiley Post, a fellow Oklahoman, grew up on a farmstead. After an Army stint in World War I, he worked as a roughneck in the Oklahoma oil fields and was arrested for armed robbery. He lost his left eye in an accident at an oil rig, but the payout from his injury provided funds that allowed him to learn to fly and acquire his own airplane. In the mid 1920s, he entered aviation as a parachutist for a flying circus.

Post broke the around-the-world record, of a little less than nine days, in 1931. He later smashed his record by nearly a day in 1933. Working with the Goodrich Company, he developed the first successful forerunner to the modern space suit. This allowed him to do an extensive amount of high altitude flying for which he gained tremendous respect in the aviation field. He won 30-35 top awards for his aviation conquests dealing with time, distance, and altitude.

Rogers and Post became friends in 1931 after Post’s around-the-world-flight. Rogers frequently mentioned Post in his newspaper column. In 1935, Post suggested a flying getaway to Rogers, who jumped at the opportunity. They had set off to explore Alaska and Russia when the accident occurred.

WHO ARE THE ESKIMOS

The Iñupiat Eskimos have always been a hunter and gatherer society living off the region’s sea and land resources. The whale, caribou, and seal have been three major sources of subsistence. The skills needed to hunt these animals have been passed down from generation to generation by the elders.

During late March, the Iñupiats establish tent camps at the edge of the ice, watching for whales from high points on land. The watch is maintained 24 hours a day. Whales pass Point Barrow in April and May on their way to their summer feeding grounds. They return south in late September and early October when this culture conducts a fall hunt. Hunts last as long as whales are in the vicinity. During unsuccessful seasons, seals, birds, and ducks have been sought instead.

When a whale is spotted, a crew of nine or ten people, led by a hunting captain, venture out in an open, sealskin-covered boat called an umiak. Up to five sealskins are used per boat depending on the vessel’s length. The skins last four years at the most. Then they turn black and start to rot.

The harpooner strikes the animal with a toggle-headed harpoon when a whale surfaces. Attached to the harpoon are two or three inflated sealskin floats made from the seals’ bladders. Each has a buoyancy of 200 to 500 pounds making it difficult for the animal to dive. A rawhide line connects the float to the harpoon. The rest of the crew cast floats, attached to the harpoon, quickly over the boat’s side. This marks where the whale is and slows it down from swimming away.

After it becomes exhausted, the animal is killed with a lance with a flint blade. The lancer severs the whale’s tendons controlling its flukes and then probes deeply into its vital organs. The crew retreats as the whale goes into a death flurry. It is then hauled to the beach where it is butchered. Dart guns with explosives and shoulder guns have replaced harpoons and lances in many cases. A number of umiak crews are needed to bring it ashore.

All available community members gather together to butcher the animal with each receiving meat and blubber. It is cut into lengths five to ten feet long and two feet wide.

Barrow has 45 captains, each responsible for their boat and crew. The village is allowed to catch 25 whales a year. Whaling feasts are held at the end of the season. A large celebration, Nalukataq, is held in June with feasts, dances, games, and the blanket toss. It is Barrow's number one attraction.

In 2016, our guide informed us that Barrow had harvested 12 whales and will hunt the rest in October. Meat is only for community consumption and is not allowed to be sold.

An attraction we saw at the coast was the Whale Bone Arch, a monument to the bowhead. This archway is made from a bowhead whale jaw from a creature caught in the 1950's. Sealskin boats surround the arch.

Caribou are usually hunted during the summer near the coast. Sometimes groups of hunters search inland for small migratory herds. In the past, they chased the animals into corrals where the men speared, snared, or shot them with bows and arrows.

During the spring and summer, attention also shifts to walruses and seals. Walruses

are pursued in a powerboat or umiak. Seals lay on top of the ice so are taken by stalking. Rifles have replaced harpoons whenever possible. Fishermen net salmon and whitefish in the rivers. Fish not eaten immediately are dried and stored or frozen in ice cellars to use during the winter. Other animals hunted are Dall sheep, ducks, and birds.

Summer has been the time of year to mine and stack veins of coal for winter fuel. Driftwood is gathered and stored if coal is not available. The Eskimos repair houses and store fresh water ice for later use in cooking and drinking. Storing meats for winter has remained vital.

Winter means the trapping season which concludes in mid March. Polar bear pelts are prized. Eskimos ice fish with lures of metal or ivory. Hunters wait patiently for seals to pop up at breathing holes then harpoon them. The seals are then pulled to the surface and killed.

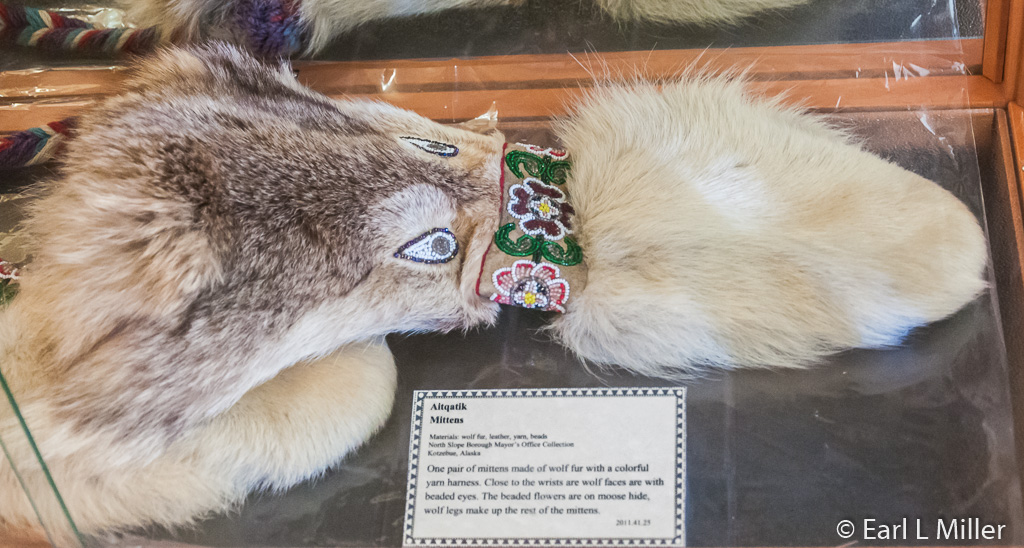

Eskimos have always used all parts of the animals. They made clothing and obtained building materials from whales, walrus, and caribou. Meat was boiled or roasted. Caribou hides became their clothing, bedding, and tents while bones and antlers were used for tools and framework for shelters. Whale baleen was used to make baskets.

Hunting using traditional methods and tools occurs today for two reasons. Community activities revolve around the seasonal subsistence cycle, and the price for grocery store food, if available, is outrageous. One web site I saw had the prices from AC Value Store from December 2014. A dozen eggs cost $5.25. Eight ounces of Lay’s potato chips was $9.49. A pound of New York strip steak was $15.99.

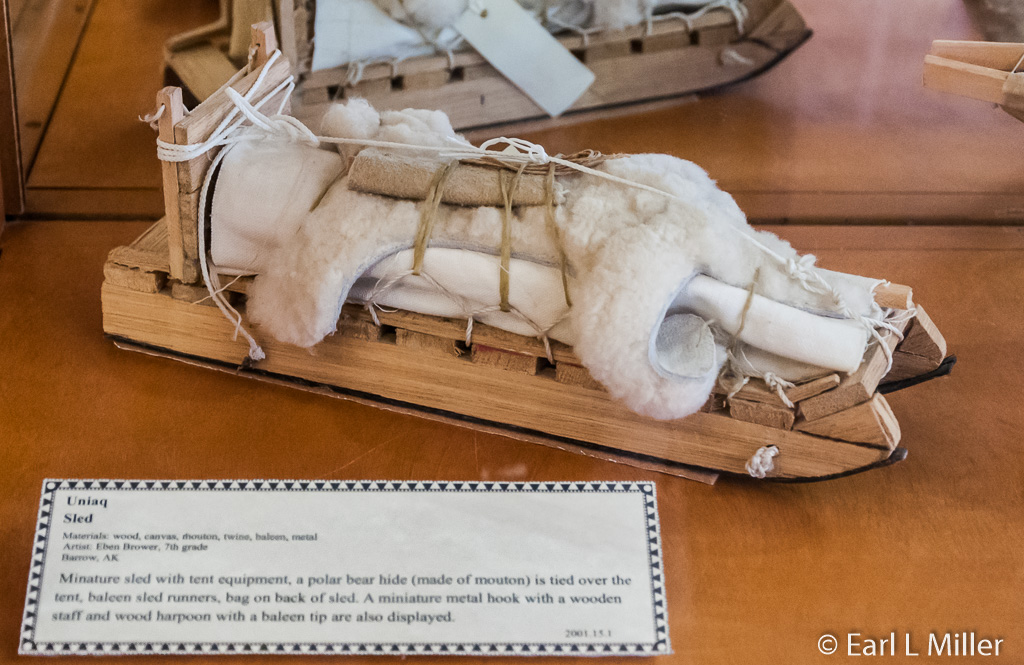

Umiaks used for long distance travel are twice as large as hunting umiaks. Up to 40 people can travel in these boats which are about 30 feet long. Basket sleds are used for land travel while flat sleds are used for hauling large skin boats across the ice.

Traditional homes consisted of driftwood, sod, and dirt. They built them partly underground for warmth. Each village had at least one community house where men lived, worked, and held celebrations. At hunting and fishing sites, they lived in skin tents or driftwood lean-tos.

Despite portrayals in movies and magazines, igloos made of stacked ice and snow were never permanent dwellings. Though it’s possible that a northern hunter stranded in a blizzard might have built one as an emergency shelter. Today their houses resemble homes you’ll find in other Alaskan cities made with plywood, vinyl siding, glass windows, and painted in a variety of colors.

It was a tradition for the whole community to bring up the children. Parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles, and big brothers and sisters were involved. Toys provided their earliest education which children received as soon as they started to walk. These included balls made of caribou skin, small bows and arrows, dolls of skin and fur, and wood spinning tops. Later they learned by listening to stories, watching their elders, and practicing life skills on their own. They mastered the skills they needed to survive by the time they became teenagers.

HERITAGE CENTER

The Iñupiat Heritage Center is an affiliated area of New Bedford (Massachusetts) Whaling National Historical Park. Its museum recognizes the contributions of Iñupiats to whaling.

More than 2,000 whaling voyages from New Bedford sailed into the Arctic during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Commercial whaling became a major activity for many Alaskan natives, particularly the Iñupiats. They crewed on the ships, hunted for food for whalers, provided fur clothing, and sheltered many shipwrecked crews.

Another purpose is to promote and perpetuate Iñupiat history, language, and culture. In the 2-1/2 hours we were at the center, besides the museum, we spotted many artifacts and watched a dance performance. We also observed native Alaskans working on skin boats and creating art made of baleen and/or ivory. Their gift shop sells local crafts, jewelry, and clothing.

The dance program provides entertainment for visitors while allowing the Eskimos to tell their stories through different motions. Each dance has its own pattern. It’s a way to remember such personal life experiences as traveling and hunting. Drummers accompany the dancers throughout their performances.

Their dances covered such topics as welcome, working, a duck walk, traveling to the cabin, and a beautiful swan. Other themes were a little old man, playing with water, paddling various boats, and chopping firewood. At the end, the audience was invited to participate in two dances.

Next came a demonstration of the Eskimo yoyo. Its inner part is made from whale baleen while the outer part consists of caribou vertebrae. A whirling toy which created a giant humming sound followed. The program closed with the song “God will Take Care of You.”

The whaling museum covers all aspects of whaling from how hunting is prepared for and conducted by the community to whaling beliefs.

Iñupiats strongly believe in reincarnation and the recycling of spirits from one life to the next. Only if animal spirits are released can they return for future harvest. Whales are revered and respected by these people who thank it for giving its life to them. Hunters are taught that whales know when you have lived a good life and only give themselves to someone worthy of their sacrifice. After the hunt, the whale is treated with the utmost respect by men and women.

We spotted beautiful clothing such as a North Slope, handmade, floral print parka with wolverine fur for ruffs and a black one with wolf fur for ruffs. We also saw a parka made from ground squirrels and ones worn on special occasions.

This area also had boots. Men’s waterproof boots are worn when whaling or for summer hunting. These were made from hairless sealskin and bearded sealskin. Soles were sewed together with caribou sinew then saturated with seal oil to waterproof them.

Another section was on setting up camp. During traditional times, the whaling crew slept outdoors. Wives brought them food daily as it was a taboo to cook where the whale was caught. Today, they use tents with kerosene heaters. They cook, boil their meat, and make hot drinks at the site.

We saw a collection from the Ice Age including tusks from a wooly mammoth. Other artifacts included collections of face masks, moccasins, and migratory birds such as the snowy owl. In the lobby, we viewed a polar bear, more outfits, a 35-foot bowhead life-size whale, and a painting titled “Hunters of the North.”

OUR TOUR

Several companies offer tours to Barrow ranging from one to several days from mid May through mid September. Northern Alaska Tour Company out of Fairbanks was the booking office for our one day tour. They handled the airline arrangements with Alaska Airline and then coordinated with Top of the World Hotel’s Tundra Tour for our four-hour tour from noon to 4:00 p.m. in Barrow. Meals were not included nor were tips.

It is possible to book Top of the World and the airline on your own. However, if you do this check the airline prices first. Top of the World charges $150 for their portion. We discovered when we checked that the total price would have been higher than the $700 we paid per person. However, I have seen nonrefundable airline prices on line, if booked far in advance, that are much cheaper than $550.

When you book through Northern Alaska Tour Company, your entire payment is required at the time of your reservation. The company applies a $75 charge per person to any change made to the reservations once confirmed including name and date changes. A cancellation fee of $150 per person exists from 30 to 8 days out. Reservations are nonrefundable if cancelled within seven days prior to the tour date. Travel insurance is available.

We had originally planned to fly to Barrow from Fairbanks. However, the cost of the tour is $50 cheaper per person if you fly out of Anchorage. It is also more convenient as you have to fly to Anchorage from Barrow and catch a connecting flight to Fairbanks.

We flew in a 737 that stopped at Dead Horse, located at Prudhoe Bay. The plane was crowded with oil workers going to their job site. Our return flight was direct on a plane where half of the seating area had been converted into a cargo section. It, too, was packed with passengers.

Our guide and a van picked us up at the airport and took us to Top of the World Hotel where we had lunch in their restaurant. Then we loaded into a 25-passenger bus which took us to the Birnirk National Historic Landmark, Whale Arch, and the Wiley Post/Will Rogers Monument.

After our stop at the Iñupiat Heritage Center, we saw the university where former military Quonset buildings from World War II have been converted into classrooms and dormitories. It has 600 students. Driving around the campus, we saw a huge bowhead whale skull. They are up to 75 feet when full grown.

We stopped by the football stadium with its blue turf, then by the Air Force Barrow Radar site. A sign there indicated it was the location of the most northern totem pole in the world. Before returning to the Top of the World Hotel, we stopped by the beach at the Arctic Ocean. When the ice retreats from the shore, you can dip your hands in the ocean. On our visit, the ice was still there so we used the opportunity to walk on it instead.

Our final stop was at Barrow's version of Wal Mart, the Alaska Commercial Company. It's a place to buy everything from clothing to souvenirs and groceries.

Our group waited at the hotel for an hour-and-a-half until it was time to return to the airport. Passing through security was easy, and soon we were on our way back to Anchorage.

We found the tour interesting to learn about the Iñupiat culture. However, due to the high price and length of the tour, four hours, I would not do it a second time. We spent more time on our airline flights than seeing the Iñupiat Heritage Center and viewing the various sites.

Phone number for Northern Alaska Tour Company is (907) 474-8600 and for Tundra Tours at Top of the World Hotel it’s (907) 852-3900.

Our Plane at Barrow Airport

Typical Modern Houses in Barrow

Street Scene of Barrow

Barrow Tribal Court

Previously Used Gas Pipeline

Sealskin Canoe

Bower Street Along the Arctic Ocean

Our Bus in Barrow

Birnirk National Historic Landmark

From the Dirt Streets of Barrow You Can Get to Anywhere

Will Rogers/Wiley Post Memorial

Whale Bone Arch at the Arctic Ocean Shore

Location of Dance Performances and a Wonderful Whaling Museum

35-Foot Whale at Center

Iñupiat Dancers

Inviting the Audience to Join the Dancers

Tent Used by Whalers

Flat Sled

Uniaq Sled

Woman's Parka with Wolverine Fur for Ruffs

Man's Parka and Waterproof Boots

Iñupiat Mask

Snowy Owl

Iñupiat Fur Boots

Mittens

Ilisagvik College

Bowhead Whale Skull on Junior College Campus

Northernmost Totem Pole in the World at Air Force Radar Site

Walking on Ice at the Arctic Ocean Shore

Alaska Commercial Company, Barrow's Version of Wal Mart