Hello Everyone,

A trip to Colorado provides opportunities to gain an understanding of the Ute culture. Our visits to museums in Montrose and Ignacio, stroll around the Ute Learning Garden in Grand Junction, and guided tour of the Ute Mountain Tribal Park in Towaoc, near Cortez, were all worth the effort.

WHO ARE THE UTES?

A thousand years ago, the Ute Indians were indigenous to the Great Basin region lying between the Rocky and the Sierra Nevada Mountains. They consisted of seven nomadic bands (tribal subdivisions) loosely organized into extended family groups from 20 to 100 people. Their survival depended on following the seasons to hunt and gather available plants and animals.

Cooperation and communication between these bands were vital. Bands would congregate for group animal hunts such as antelope or buffalo, pine nut harvests, and the annual Bear Dance.

In the early spring and the late fall, men hunted for large game such as deer, antelope, buffalo, mountain sheep, and elk. The women trapped smaller game animals such as rabbits. They also added grasshoppers and crickets to stews for extra taste and grew tobacco for use in ceremonies.

The Utes didn’t hunt animals just for their meat which was their main source of food. They used the skins for clothing and housing, animal teeth and claws for decoration, and bones for needles.

They gathered roots, pine nuts, wild potatoes and onions, seeds, and fruits. The yucca was especially prized since every part of it was used. In addition to obtaining soap from its roots, they utilized the plant to make baskets, rope, sandals, sleeping mats, and a variety of household items. Leaves were used for needles and paintbrushes. The Utes selected Three Leaf Sumac and willow to weave baskets for food and water storage. They applied pitch to make these baskets watertight.

Late in the fall, family groups started moving from the mountains to sheltered areas for the winter. Since family units lived close together, they acted as a team to acquire more wood for heating and for cooking. This larger number of family units also acted as a defense from enemy tribes.

For winter, they resided in lower elevations. It was the time to rest and gather around evening campfires to exchange stories about their lives. It was also when tools and weapons were repaired and new clothes made for the summer.

Some Utes lived in shelters called wickiups. These had round or cone shapes whose willow frame was covered with brush. Others lived in tepees. These structures had a tall cone shape supported by several poles. Skins of buffalo or other animals covered them. Homes were temporary because the Utes moved with every season to hunt.

For river travel, they built rafts. On land, before they acquired horses, they used dogs pulling travois (a kind of sled) to help them carry their belongings.

Ute women wore long dresses made of deerskin. These were fringed and accessorized with beads, shells, and elk teeth. The men wore breechcloths as well as buckskin shirts and leggings. Both sexes wore their hair loose or in a pair of braids sometimes wrapped with fur. For shoes, they wore moccasins, yucca sandals, or went barefoot. Babies were carried in cradle boards.

Depending on the band, Ute artists became known for their basketry, beadwork, and pottery. Due to their early trading contacts with the Europeans, they obtained glass beads and other items which they incorporated into religious, ceremonial, utilitarian, and warfare artifacts.

They were the only group of Indians to create ceremonial pipes from salmon alabaster and a rare black pipestone. Their pipe styles resemble those of the Great Plains Indians. The Utes have a religious aversion to handling wood from a tree struck by lightning. They believe that thunder beings would strike down any Ute that touched or handled such wood.

Their artistry can be seen in museums throughout Colorado such as the Pioneer Museum in Colorado Springs, Museum of the West in Grand Junction, and the Cortez Cultural Center in Cortez, Colorado. Story telling, consisting of many Ute legends and oral stories, passed from one generation to the next.

When the Spanish explorers arrived during the 1630s in New Mexico, they brought horses with them. The Utes obtained these animals through trade or by theft from Spanish settlements where the horses were abandoned.

The Utes were the first tribe to use horses in their everyday lives. It changed their culture tremendously. It served as their main source of transportation and allowed them to hunt further from their homes for animals such as buffalo. Possessing a horse served as a status symbol and made it possible to engage in wars against other tribes and European and American settlers.

At first, the Utes saw the settlers as friends. When their territory continued to be lessened by various government treaties and by encroachment from white settlers and mining interests, the Utes became more warlike. Over time, the Utes’ lands were reduced 90 percent. In 1873, they lost the land in the gold rich San Juan area. Following the Meeker incident in 1879, they were forced onto reservations.

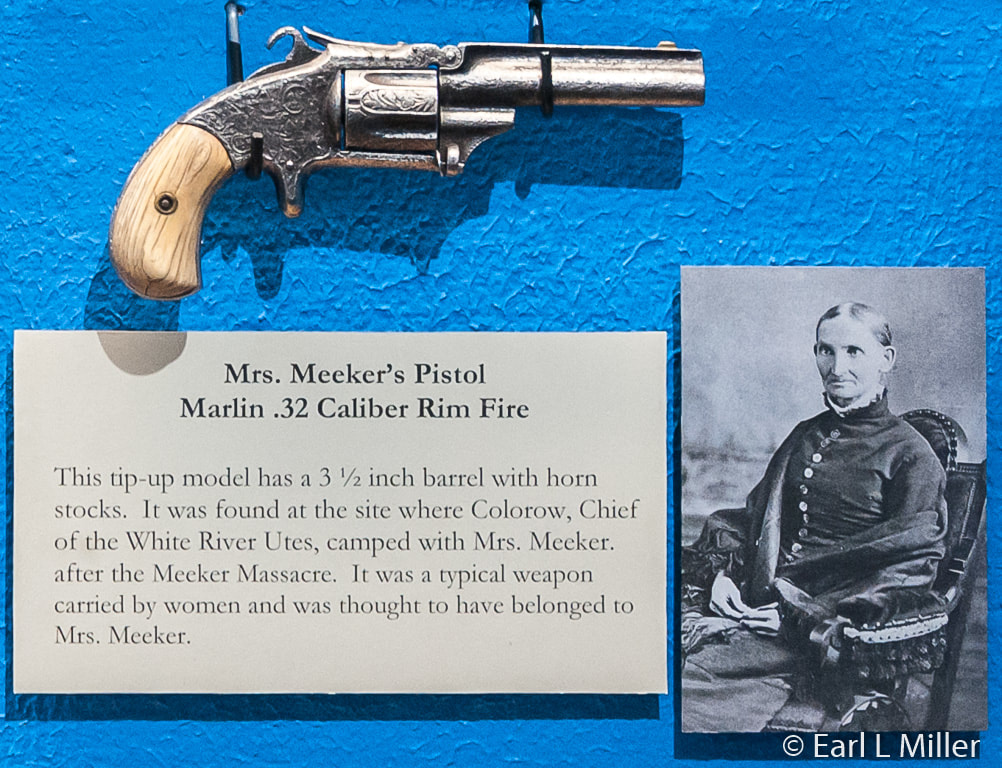

Nathaniel Meeker was an Indian agent who wanted to convert the Utes to becoming subsistence farmers instead of hunters. He was warned that the Utes resented his reforms. Meeker ignored these reports and insisted that a horse racing track be plowed under to change the track and pasture to agricultural land. The Utes considered the order an affront.

After the track was plowed, Meeker met with a Ute chief. Meeker claimed he had been assaulted by an Indian, driven from his home, and severely injured. Major Thomas Thornburgh, commander of Fort Steele in Wyoming, sent 150 to 200 soldiers. Before they arrived, on September 29, 1879, the Utes attacked the Indian agency killing Meeker and ten male employees. They held some women, including Meeker’s wife and daughter, hostage for 23 days.

Mrs. Meeker’s pistol can be seen today at the Museum of the West in Grand Junction. It was found at the site where Ute chief Colorow camped with her after the incident.

The Utes had no desire to farm. They believed that staying in one place meant starvation. Lacking agrarian skills, their farms collapsed. They turned instead to sheep herding. That did not succeed, for the most part, because of the paucity of pasture lands.

CURRENT SITUATION

Today, although they are viewed as three federally recognized tribes, they are seen by their own people as one group associated with the land for thousands of years. The Ute tribe of the Uintah and Ouray reservation have resided since 1881 at Fort Duchesne in Northeastern Utah, located approximately 150 miles from Salt Lake City. It covers 4.5 million acres and is the second largest Indian reservation in the United States.

The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 and more recent favorable actions in the 1980's resulted in the federal government granting them legal jurisdiction over more than three million acres of reservation lands. Since oil and gas have been discovered on these lands, it's hoped that the living standards will soon improve for this group.

The Southern Ute Indian Reservation is located in southwestern Colorado around Ignacio, not far from Durango. It's claimed that this is the wealthiest of the tribes since their financial assets approach two billion dollars. Their sources of income have been from gambling at their Sky Ute Casino, tourism, oil and gas, real estate leases, and various off-reservation investments.

Some of the Mountain Ute tribe moved in 1897 to the southwestern end of the Southern Ute Reservation near Towaoc. Their land includes small sections in Utah and New Mexico. Their Ute Mountain Tribal Park, the home of many Ancestral Puebloan ruins, abuts Mesa Verde National Park.

Farming and ranching enterprises were started in the 1980's for the Mountain Utes. Our guide, Gerald, at Ute Mountain Tribal Park told us they now grow corn, hay, squash, and pumpkins on an industrial scale.

Every spring, each of the tribes still celebrates the bear’s awakening from its winter’s sleep by dancing. It’s hoped that the bear will lead them to food. It also marks the spring when Mother Nature begins a new cycle, plants blossom, and animals exit their dens after their long hibernation. The dance, performed by couples, lasts for four days. On the final day, the Sundance Chief announces the dates of the Sun Dance. Held in July, this fasting and purification dance ceremony lasts for four days with dancing done by individuals instead of pairs.

Today each Ute tribe has their own government, laws, police, and services. In the past, each Ute band was ruled by a chief, usually chosen by the tribal council. Today, the tribal council is elected by all the tribal members.

UTE MOUNTAIN TRIBAL PARK

The Ute Mountain Tribal Park consists of 125,000 acres set aside to preserve artifacts of the Ancient Puebloan and Ute cultures. It is only seen by guided tour provided by the Mountain Ute tribe. Besides seeing incredible sites, tours include insight into Ute history. While following the guide in your own car is free, the ride in a 15-passenger van costs $14 extra per person.

The park has received acclaim from National Geographic Traveler who selected it as one of “80 world destinations for travel in the 21st century.” It is one of only nine places in the United States to receive this special designation. What makes it different from Mesa Verde are the lack of people and the fact that lots of artifacts have been left undisturbed. The sites have received only minimal stabilization for visitor safety. It's a low impact park.

From March or April, weather depending, through October, a 40-mile round trip, half day tour departs from the Tribal Park Visitor Center. The three-hour tour starts at 9:00 a.m. Visitors view Ancestral Puebloan petroglyphs (engravings in the rocks), Ute wall petroglyphs and pictographs (pictures on the rocks), and surface sites such as granaries and towers. Visitors also find pottery shards, tools, corn cobs, and grinding rocks. The cost is $29 per person with a 50% military discount offered to those with proof of military identification.

Entering the park, we first spotted Chimney Rock which is also known as Jackson’s Butte. William Henry Jackson, one of the West’s premier photographers, hired John Moss as a guide. Moss was the first to see the first cliff dwellings here. Between 1971 and 1976, in conjunction with the state of Colorado, the cliff dwellings had minimal stabilization.

We stopped at several places along the gravel road. Only one was close to the road. The others involved hiking on rough trails on uneven ground. One site, where we skipped the hike, involved climbing a steep mountain path for a close up view of petroglyphs. The park is definitely not ADA accessible. However, even exploration at a few sites is worth the trouble since you depart feeling the park was only recently discovered.

The Ancestral Pueblo people occupied this area from 500 A.D. to 1250 A.D. They lived initially in temporary shelters called pit houses before building cliff dwellings in the 12th and 13th centuries. The caves and overhangs helped lead to these structures’ survivals.

Our first stop was the Red Pottery site in Mancos Canyon, a Puebloan III site between 1100 and 1300 A.D. Here we spotted a kiva which is a ceremonial, round, semi-underground chamber. The Utes believed that creation came from a hole in the ground which is why kivas have holes in their centers. This kiva was part of a village that could have been a major trade center. We spotted pottery shards, basalt hammer stones, and some manos and metates for grinding corn. Our guide told us the red pottery wasn’t native but here because of trade.

At our second stop, we saw petroglyphs which weren’t far from the road. At a distance, stood a tower used for signaling or as a lookout. Next to it was a granary.

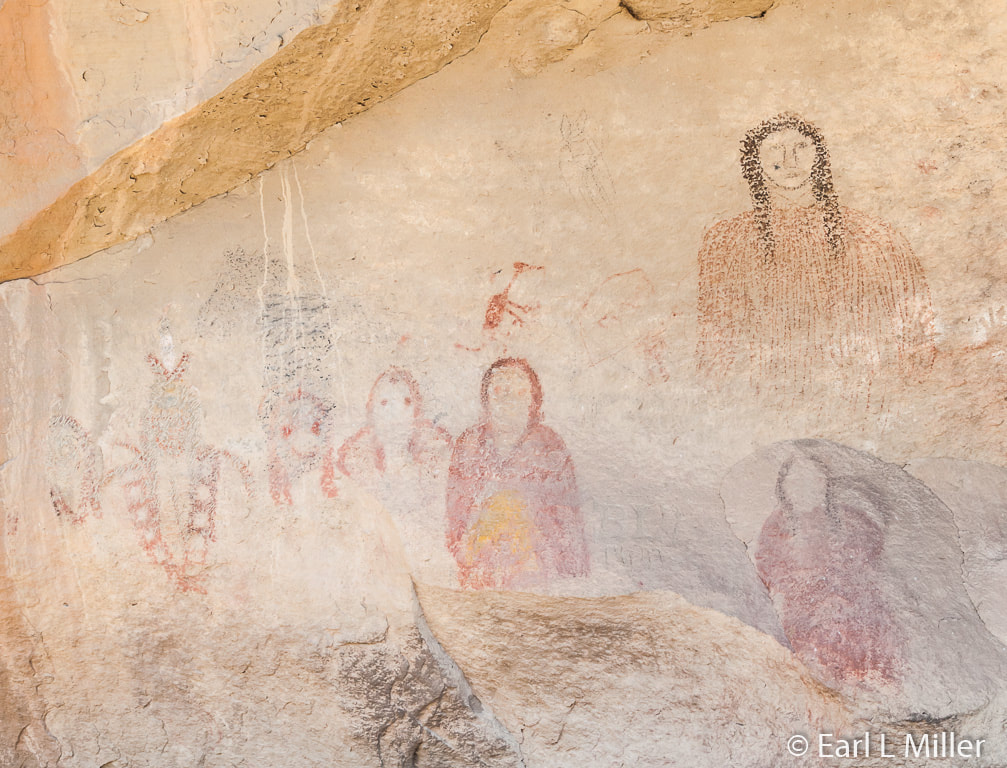

The third site was Chief Jack House’s home site. We walked back to see where he had once resided in his hogan (a five-sided lodge) to see pictographs drawn by him. He also once had sheep and horse corrals. Pictographs covered the wall with paintings of such people as a man on a half breed horse/donkey and some women and children. We also saw those of a horse and buffalo.

House went to Washington, D.C. in 1968 to have the land’s wilderness status removed. He wanted the park to start to earn money. The elders were against the tribal park since they disliked allowing outsiders onto their reservation. The young were for it. After he died, those who had opposed his plan burned down his hogan in 1976. House’s side prevailed. Tours started in 1981.

At the fourth site, we skipped seeing it up close since it involved a steep mountain trail climb on uneven ground. This site called the Spider Woman site consists of a winter solstice marker. It dates to the Basketmaker II era, about 500 A.D. The purpose of the calendar was to show the winter solstice’s exact day by how the shadows fell on the markings. Symbols on the panel represent deities of the Ancestral Pueblo people and tell stories of the cycle of life and creation. Another rock art panel had human figures in a hunting scene. We were told the animal figures on it had been assigned anthropomorphic traits.

The Great Kiva, which hasn’t been excavated, was near it. It is regarded as the largest found. Five more kivas are on top of the bluff called Kiva Point. To see them up close, it was essential to climb the steep mountain trail.

On our return we stopped at two places. The first was a granary that had been used for storage for Anasazi beans. The second was the Sun Field calendar. Upon our return, we went inside the visitor center to admire the Ute pottery.

The full day tour (80 miles round trip) adds four Anasazi cliff dwellings during the afternoon to what we had seen in the morning. To view these dwellings involves scaling four ladders. Three are about 4 feet in height while one is about 8 feet. Viewing up close Eagles Nest, the largest dwelling, requires using an optional 30-foot ladder. The hike to the dwellings is about three miles round trip. Cost for the full tour is $60. A 50% military discount is offered.

Visitors need to bring their own drinks and lunch as food is not available at the visitor center. It’s also advisable to bring an insect repellant, sun screen, a hat, and sturdy hiking shoes. Credit cards are not accepted. Personal photography is allowed.

Reservations are advisable and can be made by calling the Ute Mountain Tribal Park office at (970) 565-9653. It’s located at the junction of highways 160/491, 22 miles south of Cortez.

SOUTHERN UTE MUSEUM

Located in Ignacio, between Durango and Pagosa Springs, you’ll find a 52,000 square foot facility with collections focusing on Ute and Native Southwestern American Indians. Some of the materials are on loan from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian. It also has recorded oral histories and a growing collection of books, films, and photographs. The museum opened in 2008. I thought the building’s architecture was spectacular.

Besides meeting and classrooms, it consists of a permanent gallery providing insight on the tribe’s history and culture from the earliest times to the present. A temporary gallery had changing exhibits on such topics as pumas and mountain lions. The welcome gallery, the Circle of Life Theater, runs a 10-minute film in a 360-degree experience.

Displays include rock art, a replica house and schoolroom, and an exhibit on Utes and their horsemanship including a spring-activated, full-body horse that children can ride. Several, such as ones on farming and migration routes, are interactive. Visitors will also gain insight on the various treaties, how Indian agencies functioned, Ute family members and their roles, and the present culture of the Southern Utes.

Among its 1500 artifacts are ones of baskets, ceremonial dance regalia, other clothing, cradle boards, and paintings. They also show jewelry, belts, hair pieces, flutes, drums, weapons, stone axes, awls, and more. You’ll see a full-size tipi, ceremonial dress, and an exhibit on rodeos. Short videos are on the various traditions and on their different crafts such as beadwork.

The museum holds a variety of classes. These range from tanning animal hides to basket making, painting, sculpting, storytelling, preparing traditional foods, and cooking demonstrations. At their native garden, visitors learn about native plants, composting, medicinal horticulture, harvest feasts, and nutrition.

To read everything, plan on spending a minimum of two hours here. It is located at 503 Ouray Drive in Ignacio. Their telephone number is (970) 563-9583. Admission is free. Hours are daily 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.

UTE INDIAN MUSEUM

In Montrose, Colorado, visitors find a new building housing the Ute Indian Museum. It recently expanded from 4,650 to 8,500 feet. It sits on 8.65 acres of the original 500 acres where Chief Ouray and his wife, Chipeta, lived in the heart of Uncompahgre Ute territory.

Walking the grounds, you’ll discover Chief Ouray memorial park, the crypt of Chipeta, and a native plants garden. The complex also includes picnic areas, sculptures, nine tepees, and the Dominguez and Escalante Monument. They were the Spanish conquistadors who explored the area in 1776. A boardwalk, on one of the walking paths, leads to the Uncompahgre River. Originally built in 1956, the museum and grounds are recognized as a State Historical Monument and are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

During a three-year period, History Colorado (which oversees the Ute Indian Museum and eight other community museums across Colorado) worked with representatives of all three tribes: Mountain Utes, Southern Utes and the Ute Indian Tribe of the Unitah and Ouray Reservation in Utah on developing the building’s design and displays. Exhibits are on all the tribes.

Inside, the interior has been totally redone. It now contains the Montrose Visitor Information Center, gallery space, a large multi purpose room for programs and rentals, and a museum store. Its artifact collection on the Utes is regarded as one of the nation’s most complete. A library holds 1,500 books on their culture.

Exhibits and presentations tie the past to the contemporary. Displays center on the geographic relating various stories of different Ute regions as they pertain to a tribe or individual lives. Walking around we didn’t see any interactives or dioramas. However, we did notice all sorts of Ute items including clothing.

They have buckskin garments including Chief Ouray’s shirt, Chipeta’s dress, Buckskin Charlie’s headdress, and large cases of beadwork and ceremonial dress. They also have Chipeta’s saddle and saddle blankets.

Artwork includes paintings by members of the three Ute tribes and a display of pottery. In the lobby, a layout of many tiles represents beadwork. The museum also has four videos including one of the Bear Dance.

Signs cover a variety of subjects. These range from the family as the Ute center of life to their trade network and life at tribal schools. Others are on treaties with the United States government, how they govern today, the creation story, and housing from wickiups to modern residences with solar hearing. There are separate cases devoted to the Southern Ute and Mountain Ute tribes.

A special ceremony, open only to Utes, occurred June 9, 2017. It consisted of a sunrise service, ribbon cutting, story telling, and a buffalo feast. On June 10, the public grand opening was held. Since that time, interior photos of the exhibits have been permitted. Unfortunately, on our May visit, we weren’t allowed to take interior shots.

It is located at 17253 Chipeta Road, three miles from downtown Montrose, Colorado, on U.S. Highway 550. The telephone number is (970) 249-3098. Hours are Monday through Saturday 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. and on Sundays from 11:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. Admission is $6 for adults, $5 for seniors ages 65 and older, $3.50 for children ages 7-16, and free for those ages six and under. May through Labor Day, children, ages 18 and under, are free. AAA discounts are offered.

THE UTE LEARNING GARDEN

Located in Grand Junction, Colorado, visitors find the 2.5 acre Ute Learning Garden. It’s an ethnobotany teaching garden whose main purpose is providing a living laboratory on native plants and how they were used in ancestral times for food, medicine, and fiber. It also teaches stewardship of natural resources, exhibits life zones representing the ecosystems of Western Colorado, and teaches the public about native landscaping and low water use plants.

The park was created through the cooperative effort of the Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Forest Service, Tri River Colorado State University Extension Service, Colorado Mesa University, and Ute tribe of the Unitah and Ouray Reservation.

In 2008, permission was granted to build the garden adjacent to the CSU facility’s cactus garden and office. The idea was to create a garden to interpret how plants were used by the Native Americans of Western Colorado. It would depict eco-zones representing riparian, desert shrub, pinon-juniper woodlands, oak brush, and alpine.

In 2009, Chelsea Nursery donated many of the native plants. Ute students, under Master Gardener guidance, then planted them. The B.L.M. in conjunction with Tri River placed irrigation pipes, interpretative signs, landscaping, and ramada (shelter type) posts.

They also planted a small garden called the Three Sisters Garden of corn, beans, and squash. The Utes had gardens instead of fields of corn. Manos and metates were left near the garden enabling students to grind their own corn flour and wild seeds.

Starting in 2014, the Ute tribe and a team of Master Gardeners have expanded the garden annually with native plants. New construction has also taken place each year with such additions as a wickiup, a tepee, and informational signs. Master Gardeners continue to maintain the garden. The Utes' elders must approve any improvements before they’re instituted.

On our visit to the garden, we met with Master Gardeners Jan Klahn and Martha Hartung for a very interesting tour. They told us that the Utes believe in thanking the earth with prayer and tobacco offerings as they harvest the various plants. They give offerings at sites where they believe their ancestors prayed or where plants were collected. The Utes also show respect for nature by the wise use and harvesting of plants.

We then learned about some of the garden’s plants. For instance, the pinon pine nuts are high in calories and protein. When a Pinon Jay is seen on a tree eating nuts, it’s time to harvest. A blanket is placed around the tree. It is then shaken so that the nuts fall. How much moisture the tree receives determines the size of the crop. They live well over a hundred years.

The Utes used Skunkbrush to weave their baskets. The plant’s red berries were used to make a lemonade type sour drink which was sometimes a little salty. Greasewood was used for tools and firewood as well as to waterproof baskets.

They used all parts of the Fourwing Saltbrush plant. They added it to corn to increase nutrition and as baking powder. It was used for basketry. The plant could change sexes when it needed to be more bountiful.

The Utes used a lot of plants for medicinal purposes. For instance, Winterfat, besides being good foliage for elk, deer, and horses, was used to dress burns and treat fevers. Greasewood roots were used to treat toothaches.

Spending time walking around the garden, we noticed a very small sweat lodge which the public is not allowed to enter. The Utes heat these with rocks. The experience they have in such a lodge enables them to make a spiritual connection.

A tepee is also on the grounds which they allow students to enter as long as they do it correctly. Each time, entrance must be first with the left foot. Then they must put their feet together and stop. They need to walk clockwise all the way around the tepee before exiting. This is because the Utes honor the sun and the sun faces east when it rises. By walking this way, they are respecting the sun’s path.

A number of signs are interspersed among the plants. The first relates the purpose of the garden and invites people to follow the trails. Another tells the Ute creation story. Others provide Ute history from their arrival in Colorado through the 1800s. Dates of various removals are given.

The sign “Who Lives Here” tells how everything in nature is interconnected. Plants, animal, and nonliving environmental components interact to form relationships that help all to survive. “Plants in the Desert” describes how the various leaves survive. For example, fuzzy leaves collect dew and rain water.

“The Ground is Alive” mentions that crypto (secret) biotic (living) soil creates a bond between plants and desert soil. The living soil acts like a sponge when thunderstorms occur protecting the land from erosion. Foot trail and tire tracks can last for decades in this soil and start a cycle of erosion that is hard to control. By not stepping on cryptobiotic soil, it keeps plants and animals healthy.

At the Three Sisters Garden, one learns that corn provides structure for the climbing beans. Beans add nitrogen to the soil for other plants. Squash creates a living mulch as it shades the soil, preserving moisture and preventing weeds. They work together to provide carbohydrates, proteins, vitamins, and essential amino acids so most Native American tribes can thrive on a plant-based diet. Some tribes added a fourth sister to aid in pollination. At Ute Learning Garden, they added sunflowers.

“Why Circles,” the last sign we saw, describes why the circle is considered the most important shape in Ute life. Many things are circular such as the seasons, the earth, the sun and moon, birds’ nests, how tepees are set up, and campfire rings.

The Ute Learning Garden is located at 2775 Highway 50 in Grand Junction. For information on classes or to schedule a group tour, call (970) 244-1834. This park has no hours or admission fees so can be visited at any time.

A trip to Colorado provides opportunities to gain an understanding of the Ute culture. Our visits to museums in Montrose and Ignacio, stroll around the Ute Learning Garden in Grand Junction, and guided tour of the Ute Mountain Tribal Park in Towaoc, near Cortez, were all worth the effort.

WHO ARE THE UTES?

A thousand years ago, the Ute Indians were indigenous to the Great Basin region lying between the Rocky and the Sierra Nevada Mountains. They consisted of seven nomadic bands (tribal subdivisions) loosely organized into extended family groups from 20 to 100 people. Their survival depended on following the seasons to hunt and gather available plants and animals.

Cooperation and communication between these bands were vital. Bands would congregate for group animal hunts such as antelope or buffalo, pine nut harvests, and the annual Bear Dance.

In the early spring and the late fall, men hunted for large game such as deer, antelope, buffalo, mountain sheep, and elk. The women trapped smaller game animals such as rabbits. They also added grasshoppers and crickets to stews for extra taste and grew tobacco for use in ceremonies.

The Utes didn’t hunt animals just for their meat which was their main source of food. They used the skins for clothing and housing, animal teeth and claws for decoration, and bones for needles.

They gathered roots, pine nuts, wild potatoes and onions, seeds, and fruits. The yucca was especially prized since every part of it was used. In addition to obtaining soap from its roots, they utilized the plant to make baskets, rope, sandals, sleeping mats, and a variety of household items. Leaves were used for needles and paintbrushes. The Utes selected Three Leaf Sumac and willow to weave baskets for food and water storage. They applied pitch to make these baskets watertight.

Late in the fall, family groups started moving from the mountains to sheltered areas for the winter. Since family units lived close together, they acted as a team to acquire more wood for heating and for cooking. This larger number of family units also acted as a defense from enemy tribes.

For winter, they resided in lower elevations. It was the time to rest and gather around evening campfires to exchange stories about their lives. It was also when tools and weapons were repaired and new clothes made for the summer.

Some Utes lived in shelters called wickiups. These had round or cone shapes whose willow frame was covered with brush. Others lived in tepees. These structures had a tall cone shape supported by several poles. Skins of buffalo or other animals covered them. Homes were temporary because the Utes moved with every season to hunt.

For river travel, they built rafts. On land, before they acquired horses, they used dogs pulling travois (a kind of sled) to help them carry their belongings.

Ute women wore long dresses made of deerskin. These were fringed and accessorized with beads, shells, and elk teeth. The men wore breechcloths as well as buckskin shirts and leggings. Both sexes wore their hair loose or in a pair of braids sometimes wrapped with fur. For shoes, they wore moccasins, yucca sandals, or went barefoot. Babies were carried in cradle boards.

Depending on the band, Ute artists became known for their basketry, beadwork, and pottery. Due to their early trading contacts with the Europeans, they obtained glass beads and other items which they incorporated into religious, ceremonial, utilitarian, and warfare artifacts.

They were the only group of Indians to create ceremonial pipes from salmon alabaster and a rare black pipestone. Their pipe styles resemble those of the Great Plains Indians. The Utes have a religious aversion to handling wood from a tree struck by lightning. They believe that thunder beings would strike down any Ute that touched or handled such wood.

Their artistry can be seen in museums throughout Colorado such as the Pioneer Museum in Colorado Springs, Museum of the West in Grand Junction, and the Cortez Cultural Center in Cortez, Colorado. Story telling, consisting of many Ute legends and oral stories, passed from one generation to the next.

When the Spanish explorers arrived during the 1630s in New Mexico, they brought horses with them. The Utes obtained these animals through trade or by theft from Spanish settlements where the horses were abandoned.

The Utes were the first tribe to use horses in their everyday lives. It changed their culture tremendously. It served as their main source of transportation and allowed them to hunt further from their homes for animals such as buffalo. Possessing a horse served as a status symbol and made it possible to engage in wars against other tribes and European and American settlers.

At first, the Utes saw the settlers as friends. When their territory continued to be lessened by various government treaties and by encroachment from white settlers and mining interests, the Utes became more warlike. Over time, the Utes’ lands were reduced 90 percent. In 1873, they lost the land in the gold rich San Juan area. Following the Meeker incident in 1879, they were forced onto reservations.

Nathaniel Meeker was an Indian agent who wanted to convert the Utes to becoming subsistence farmers instead of hunters. He was warned that the Utes resented his reforms. Meeker ignored these reports and insisted that a horse racing track be plowed under to change the track and pasture to agricultural land. The Utes considered the order an affront.

After the track was plowed, Meeker met with a Ute chief. Meeker claimed he had been assaulted by an Indian, driven from his home, and severely injured. Major Thomas Thornburgh, commander of Fort Steele in Wyoming, sent 150 to 200 soldiers. Before they arrived, on September 29, 1879, the Utes attacked the Indian agency killing Meeker and ten male employees. They held some women, including Meeker’s wife and daughter, hostage for 23 days.

Mrs. Meeker’s pistol can be seen today at the Museum of the West in Grand Junction. It was found at the site where Ute chief Colorow camped with her after the incident.

The Utes had no desire to farm. They believed that staying in one place meant starvation. Lacking agrarian skills, their farms collapsed. They turned instead to sheep herding. That did not succeed, for the most part, because of the paucity of pasture lands.

CURRENT SITUATION

Today, although they are viewed as three federally recognized tribes, they are seen by their own people as one group associated with the land for thousands of years. The Ute tribe of the Uintah and Ouray reservation have resided since 1881 at Fort Duchesne in Northeastern Utah, located approximately 150 miles from Salt Lake City. It covers 4.5 million acres and is the second largest Indian reservation in the United States.

The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 and more recent favorable actions in the 1980's resulted in the federal government granting them legal jurisdiction over more than three million acres of reservation lands. Since oil and gas have been discovered on these lands, it's hoped that the living standards will soon improve for this group.

The Southern Ute Indian Reservation is located in southwestern Colorado around Ignacio, not far from Durango. It's claimed that this is the wealthiest of the tribes since their financial assets approach two billion dollars. Their sources of income have been from gambling at their Sky Ute Casino, tourism, oil and gas, real estate leases, and various off-reservation investments.

Some of the Mountain Ute tribe moved in 1897 to the southwestern end of the Southern Ute Reservation near Towaoc. Their land includes small sections in Utah and New Mexico. Their Ute Mountain Tribal Park, the home of many Ancestral Puebloan ruins, abuts Mesa Verde National Park.

Farming and ranching enterprises were started in the 1980's for the Mountain Utes. Our guide, Gerald, at Ute Mountain Tribal Park told us they now grow corn, hay, squash, and pumpkins on an industrial scale.

Every spring, each of the tribes still celebrates the bear’s awakening from its winter’s sleep by dancing. It’s hoped that the bear will lead them to food. It also marks the spring when Mother Nature begins a new cycle, plants blossom, and animals exit their dens after their long hibernation. The dance, performed by couples, lasts for four days. On the final day, the Sundance Chief announces the dates of the Sun Dance. Held in July, this fasting and purification dance ceremony lasts for four days with dancing done by individuals instead of pairs.

Today each Ute tribe has their own government, laws, police, and services. In the past, each Ute band was ruled by a chief, usually chosen by the tribal council. Today, the tribal council is elected by all the tribal members.

UTE MOUNTAIN TRIBAL PARK

The Ute Mountain Tribal Park consists of 125,000 acres set aside to preserve artifacts of the Ancient Puebloan and Ute cultures. It is only seen by guided tour provided by the Mountain Ute tribe. Besides seeing incredible sites, tours include insight into Ute history. While following the guide in your own car is free, the ride in a 15-passenger van costs $14 extra per person.

The park has received acclaim from National Geographic Traveler who selected it as one of “80 world destinations for travel in the 21st century.” It is one of only nine places in the United States to receive this special designation. What makes it different from Mesa Verde are the lack of people and the fact that lots of artifacts have been left undisturbed. The sites have received only minimal stabilization for visitor safety. It's a low impact park.

From March or April, weather depending, through October, a 40-mile round trip, half day tour departs from the Tribal Park Visitor Center. The three-hour tour starts at 9:00 a.m. Visitors view Ancestral Puebloan petroglyphs (engravings in the rocks), Ute wall petroglyphs and pictographs (pictures on the rocks), and surface sites such as granaries and towers. Visitors also find pottery shards, tools, corn cobs, and grinding rocks. The cost is $29 per person with a 50% military discount offered to those with proof of military identification.

Entering the park, we first spotted Chimney Rock which is also known as Jackson’s Butte. William Henry Jackson, one of the West’s premier photographers, hired John Moss as a guide. Moss was the first to see the first cliff dwellings here. Between 1971 and 1976, in conjunction with the state of Colorado, the cliff dwellings had minimal stabilization.

We stopped at several places along the gravel road. Only one was close to the road. The others involved hiking on rough trails on uneven ground. One site, where we skipped the hike, involved climbing a steep mountain path for a close up view of petroglyphs. The park is definitely not ADA accessible. However, even exploration at a few sites is worth the trouble since you depart feeling the park was only recently discovered.

The Ancestral Pueblo people occupied this area from 500 A.D. to 1250 A.D. They lived initially in temporary shelters called pit houses before building cliff dwellings in the 12th and 13th centuries. The caves and overhangs helped lead to these structures’ survivals.

Our first stop was the Red Pottery site in Mancos Canyon, a Puebloan III site between 1100 and 1300 A.D. Here we spotted a kiva which is a ceremonial, round, semi-underground chamber. The Utes believed that creation came from a hole in the ground which is why kivas have holes in their centers. This kiva was part of a village that could have been a major trade center. We spotted pottery shards, basalt hammer stones, and some manos and metates for grinding corn. Our guide told us the red pottery wasn’t native but here because of trade.

At our second stop, we saw petroglyphs which weren’t far from the road. At a distance, stood a tower used for signaling or as a lookout. Next to it was a granary.

The third site was Chief Jack House’s home site. We walked back to see where he had once resided in his hogan (a five-sided lodge) to see pictographs drawn by him. He also once had sheep and horse corrals. Pictographs covered the wall with paintings of such people as a man on a half breed horse/donkey and some women and children. We also saw those of a horse and buffalo.

House went to Washington, D.C. in 1968 to have the land’s wilderness status removed. He wanted the park to start to earn money. The elders were against the tribal park since they disliked allowing outsiders onto their reservation. The young were for it. After he died, those who had opposed his plan burned down his hogan in 1976. House’s side prevailed. Tours started in 1981.

At the fourth site, we skipped seeing it up close since it involved a steep mountain trail climb on uneven ground. This site called the Spider Woman site consists of a winter solstice marker. It dates to the Basketmaker II era, about 500 A.D. The purpose of the calendar was to show the winter solstice’s exact day by how the shadows fell on the markings. Symbols on the panel represent deities of the Ancestral Pueblo people and tell stories of the cycle of life and creation. Another rock art panel had human figures in a hunting scene. We were told the animal figures on it had been assigned anthropomorphic traits.

The Great Kiva, which hasn’t been excavated, was near it. It is regarded as the largest found. Five more kivas are on top of the bluff called Kiva Point. To see them up close, it was essential to climb the steep mountain trail.

On our return we stopped at two places. The first was a granary that had been used for storage for Anasazi beans. The second was the Sun Field calendar. Upon our return, we went inside the visitor center to admire the Ute pottery.

The full day tour (80 miles round trip) adds four Anasazi cliff dwellings during the afternoon to what we had seen in the morning. To view these dwellings involves scaling four ladders. Three are about 4 feet in height while one is about 8 feet. Viewing up close Eagles Nest, the largest dwelling, requires using an optional 30-foot ladder. The hike to the dwellings is about three miles round trip. Cost for the full tour is $60. A 50% military discount is offered.

Visitors need to bring their own drinks and lunch as food is not available at the visitor center. It’s also advisable to bring an insect repellant, sun screen, a hat, and sturdy hiking shoes. Credit cards are not accepted. Personal photography is allowed.

Reservations are advisable and can be made by calling the Ute Mountain Tribal Park office at (970) 565-9653. It’s located at the junction of highways 160/491, 22 miles south of Cortez.

SOUTHERN UTE MUSEUM

Located in Ignacio, between Durango and Pagosa Springs, you’ll find a 52,000 square foot facility with collections focusing on Ute and Native Southwestern American Indians. Some of the materials are on loan from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian. It also has recorded oral histories and a growing collection of books, films, and photographs. The museum opened in 2008. I thought the building’s architecture was spectacular.

Besides meeting and classrooms, it consists of a permanent gallery providing insight on the tribe’s history and culture from the earliest times to the present. A temporary gallery had changing exhibits on such topics as pumas and mountain lions. The welcome gallery, the Circle of Life Theater, runs a 10-minute film in a 360-degree experience.

Displays include rock art, a replica house and schoolroom, and an exhibit on Utes and their horsemanship including a spring-activated, full-body horse that children can ride. Several, such as ones on farming and migration routes, are interactive. Visitors will also gain insight on the various treaties, how Indian agencies functioned, Ute family members and their roles, and the present culture of the Southern Utes.

Among its 1500 artifacts are ones of baskets, ceremonial dance regalia, other clothing, cradle boards, and paintings. They also show jewelry, belts, hair pieces, flutes, drums, weapons, stone axes, awls, and more. You’ll see a full-size tipi, ceremonial dress, and an exhibit on rodeos. Short videos are on the various traditions and on their different crafts such as beadwork.

The museum holds a variety of classes. These range from tanning animal hides to basket making, painting, sculpting, storytelling, preparing traditional foods, and cooking demonstrations. At their native garden, visitors learn about native plants, composting, medicinal horticulture, harvest feasts, and nutrition.

To read everything, plan on spending a minimum of two hours here. It is located at 503 Ouray Drive in Ignacio. Their telephone number is (970) 563-9583. Admission is free. Hours are daily 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.

UTE INDIAN MUSEUM

In Montrose, Colorado, visitors find a new building housing the Ute Indian Museum. It recently expanded from 4,650 to 8,500 feet. It sits on 8.65 acres of the original 500 acres where Chief Ouray and his wife, Chipeta, lived in the heart of Uncompahgre Ute territory.

Walking the grounds, you’ll discover Chief Ouray memorial park, the crypt of Chipeta, and a native plants garden. The complex also includes picnic areas, sculptures, nine tepees, and the Dominguez and Escalante Monument. They were the Spanish conquistadors who explored the area in 1776. A boardwalk, on one of the walking paths, leads to the Uncompahgre River. Originally built in 1956, the museum and grounds are recognized as a State Historical Monument and are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

During a three-year period, History Colorado (which oversees the Ute Indian Museum and eight other community museums across Colorado) worked with representatives of all three tribes: Mountain Utes, Southern Utes and the Ute Indian Tribe of the Unitah and Ouray Reservation in Utah on developing the building’s design and displays. Exhibits are on all the tribes.

Inside, the interior has been totally redone. It now contains the Montrose Visitor Information Center, gallery space, a large multi purpose room for programs and rentals, and a museum store. Its artifact collection on the Utes is regarded as one of the nation’s most complete. A library holds 1,500 books on their culture.

Exhibits and presentations tie the past to the contemporary. Displays center on the geographic relating various stories of different Ute regions as they pertain to a tribe or individual lives. Walking around we didn’t see any interactives or dioramas. However, we did notice all sorts of Ute items including clothing.

They have buckskin garments including Chief Ouray’s shirt, Chipeta’s dress, Buckskin Charlie’s headdress, and large cases of beadwork and ceremonial dress. They also have Chipeta’s saddle and saddle blankets.

Artwork includes paintings by members of the three Ute tribes and a display of pottery. In the lobby, a layout of many tiles represents beadwork. The museum also has four videos including one of the Bear Dance.

Signs cover a variety of subjects. These range from the family as the Ute center of life to their trade network and life at tribal schools. Others are on treaties with the United States government, how they govern today, the creation story, and housing from wickiups to modern residences with solar hearing. There are separate cases devoted to the Southern Ute and Mountain Ute tribes.

A special ceremony, open only to Utes, occurred June 9, 2017. It consisted of a sunrise service, ribbon cutting, story telling, and a buffalo feast. On June 10, the public grand opening was held. Since that time, interior photos of the exhibits have been permitted. Unfortunately, on our May visit, we weren’t allowed to take interior shots.

It is located at 17253 Chipeta Road, three miles from downtown Montrose, Colorado, on U.S. Highway 550. The telephone number is (970) 249-3098. Hours are Monday through Saturday 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. and on Sundays from 11:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. Admission is $6 for adults, $5 for seniors ages 65 and older, $3.50 for children ages 7-16, and free for those ages six and under. May through Labor Day, children, ages 18 and under, are free. AAA discounts are offered.

THE UTE LEARNING GARDEN

Located in Grand Junction, Colorado, visitors find the 2.5 acre Ute Learning Garden. It’s an ethnobotany teaching garden whose main purpose is providing a living laboratory on native plants and how they were used in ancestral times for food, medicine, and fiber. It also teaches stewardship of natural resources, exhibits life zones representing the ecosystems of Western Colorado, and teaches the public about native landscaping and low water use plants.

The park was created through the cooperative effort of the Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Forest Service, Tri River Colorado State University Extension Service, Colorado Mesa University, and Ute tribe of the Unitah and Ouray Reservation.

In 2008, permission was granted to build the garden adjacent to the CSU facility’s cactus garden and office. The idea was to create a garden to interpret how plants were used by the Native Americans of Western Colorado. It would depict eco-zones representing riparian, desert shrub, pinon-juniper woodlands, oak brush, and alpine.

In 2009, Chelsea Nursery donated many of the native plants. Ute students, under Master Gardener guidance, then planted them. The B.L.M. in conjunction with Tri River placed irrigation pipes, interpretative signs, landscaping, and ramada (shelter type) posts.

They also planted a small garden called the Three Sisters Garden of corn, beans, and squash. The Utes had gardens instead of fields of corn. Manos and metates were left near the garden enabling students to grind their own corn flour and wild seeds.

Starting in 2014, the Ute tribe and a team of Master Gardeners have expanded the garden annually with native plants. New construction has also taken place each year with such additions as a wickiup, a tepee, and informational signs. Master Gardeners continue to maintain the garden. The Utes' elders must approve any improvements before they’re instituted.

On our visit to the garden, we met with Master Gardeners Jan Klahn and Martha Hartung for a very interesting tour. They told us that the Utes believe in thanking the earth with prayer and tobacco offerings as they harvest the various plants. They give offerings at sites where they believe their ancestors prayed or where plants were collected. The Utes also show respect for nature by the wise use and harvesting of plants.

We then learned about some of the garden’s plants. For instance, the pinon pine nuts are high in calories and protein. When a Pinon Jay is seen on a tree eating nuts, it’s time to harvest. A blanket is placed around the tree. It is then shaken so that the nuts fall. How much moisture the tree receives determines the size of the crop. They live well over a hundred years.

The Utes used Skunkbrush to weave their baskets. The plant’s red berries were used to make a lemonade type sour drink which was sometimes a little salty. Greasewood was used for tools and firewood as well as to waterproof baskets.

They used all parts of the Fourwing Saltbrush plant. They added it to corn to increase nutrition and as baking powder. It was used for basketry. The plant could change sexes when it needed to be more bountiful.

The Utes used a lot of plants for medicinal purposes. For instance, Winterfat, besides being good foliage for elk, deer, and horses, was used to dress burns and treat fevers. Greasewood roots were used to treat toothaches.

Spending time walking around the garden, we noticed a very small sweat lodge which the public is not allowed to enter. The Utes heat these with rocks. The experience they have in such a lodge enables them to make a spiritual connection.

A tepee is also on the grounds which they allow students to enter as long as they do it correctly. Each time, entrance must be first with the left foot. Then they must put their feet together and stop. They need to walk clockwise all the way around the tepee before exiting. This is because the Utes honor the sun and the sun faces east when it rises. By walking this way, they are respecting the sun’s path.

A number of signs are interspersed among the plants. The first relates the purpose of the garden and invites people to follow the trails. Another tells the Ute creation story. Others provide Ute history from their arrival in Colorado through the 1800s. Dates of various removals are given.

The sign “Who Lives Here” tells how everything in nature is interconnected. Plants, animal, and nonliving environmental components interact to form relationships that help all to survive. “Plants in the Desert” describes how the various leaves survive. For example, fuzzy leaves collect dew and rain water.

“The Ground is Alive” mentions that crypto (secret) biotic (living) soil creates a bond between plants and desert soil. The living soil acts like a sponge when thunderstorms occur protecting the land from erosion. Foot trail and tire tracks can last for decades in this soil and start a cycle of erosion that is hard to control. By not stepping on cryptobiotic soil, it keeps plants and animals healthy.

At the Three Sisters Garden, one learns that corn provides structure for the climbing beans. Beans add nitrogen to the soil for other plants. Squash creates a living mulch as it shades the soil, preserving moisture and preventing weeds. They work together to provide carbohydrates, proteins, vitamins, and essential amino acids so most Native American tribes can thrive on a plant-based diet. Some tribes added a fourth sister to aid in pollination. At Ute Learning Garden, they added sunflowers.

“Why Circles,” the last sign we saw, describes why the circle is considered the most important shape in Ute life. Many things are circular such as the seasons, the earth, the sun and moon, birds’ nests, how tepees are set up, and campfire rings.

The Ute Learning Garden is located at 2775 Highway 50 in Grand Junction. For information on classes or to schedule a group tour, call (970) 244-1834. This park has no hours or admission fees so can be visited at any time.

Mrs. Meeker's Pistol at Museum of the West

Our Guide, Gerald Ketchum Explaining One of the Pottery Shards

Red Mano with Pottery Shards

More of the Pottery Shards

Petroglyphs at Our Second Stop

More Petroglyphs at the Second Stop

Pictographs by Chief Jack House at Third Stop

More Pictographs by Chief Jack House

Gerald Pointing Out Spider Woman Site

Wall Loaded with Petroglyphs at Spider Woman Site

Cliff Dwelling Used for Storage

Exterior of Southern Ute Museum

Rock Art at Southern Ute Museum

Tepee at Southern Ute Museum

Women's Garments Displayed at Southern Ute Museum

Men's Garments at Southern Ute Museum

Horsemanship Display at Southern Ute Museum

Typical House Display at Southern Ute Museum

Ute Indian Museum at Montrose

Entrance to Ute Learning Garden

Pinyon Pines at Ute Learning Garden

Skunkbrush at the Ute Learning Garden

Tepee Frames at Ute Learning Garden

Yucca at Ute Learning Garden

Ramada at Ute Learning Garden

Ecological Circles at Ute Learning Garden