Hello Everyone,

Located approximately 17 miles from Mount Rushmore, near Custer City, visitors find the largest sculpture on Earth being created on Thunderhead Mountain. It’s the Crazy Horse Memorial® which has been under construction since 1948.

The monument depicts the Oglala Lakota warrior Crazy Horse sitting on a horse and pointing to his lands in the distance. It was commissioned by Henry Standing Bear, a Lakota elder, to be sculpted by Korczak Ziolkowski. When Korczak died in 1982, his wife Ruth headed the project until her death in 2014. The second and third generations of this family now carry on this work. No date has been set for the memorial’s completion.

The Crazy Horse Memorial Foundation®, a nonprofit organization, operates Crazy Horse, supervising its continuing progress. However, it is concerned with more than just this extensive sculpture. Its mission is to protect and preserve the culture, tradition, and living heritage of the North American Indians.

The Foundation’s Indian Museum of North America® and its The Native American Educational and Cultural Center® act as repositories for artifacts, crafts, and arts representing more than 50 tribes. The Indian University of North America® provides courses. In the future, it hopes to open a medical training center for American Indians. All of these are on the monument’s campus in addition to a Welcome Center, the Ziolkowski home, Korczak’s sculptor studio, and various other museums.

CRAZY HORSE

Crazy Horse was not a chief but a highly regarded warrior who was ferocious in battle. He was recognized by his people as a leader committed to preserving the traditions and values of the Lakota way of life.

Before he was thirteen, he stole horses from the Crow Indians and led his first war party before turning twenty. He was instrumental in the 1865-68 war that Oglala chief Red Cloud led against Wyoming’s settlers. In 1867, Crazy Horse played a key role in destroying William J. Fetterman’s brigade at Fort Kearny, Nebraska.

Crazy Horse provided resistance to American encroachment on Lakota lands. In 1873, he attacked a surveying party sent into the Black Hills by General George Armstrong Custer. When all Lakota bands were ordered by the War Department onto reservations in 1876, Crazy Horse again led the fight.

Due to his first wife being Cheyenne, he allied with the Cheyenne. In June 17, 1876, he gathered together a force of 1,200 Oglala and Cheyenne at his village. He turned back General George Crook, who had tried to advance to Sitting Bull’s encampment on the Little Bighorn.

On June 25, 1876, Crazy Horse’s force joined with Sitting Bull to destroy Custer’s Seventh Cavalry at the Battle of Little Bighorn. While Chief Gall and his Hunkpapa warriors charged from the south and east, Crazy Horse’s braves flanked the cavalry from the north and west.

After that battle, Gall and Sitting Bull left for Canada. However, Crazy Horse continued to harass the United States Army. He battled General Nelson Miles during the winter of 1876-77.

When Crazy Horse left the reservation without authorization to take his sick wife to her parents, General Crook arrested him and took him to Fort Robinson, Nebraska on May 5, 1877. Crazy Horse struggled against being taken to a guardhouse. While his arms were held by one of the arresting officers, a soldier ran him through with a bayonet. He died on May 6, 1877.

KORCZAK ZIOLKOWSKI

Visitors to the memorial can learn about Korczak’s story while visiting his log studio-home, workshop, and sculptural galleries at Crazy Horse.

Born in Boston of Polish descent, Korczak became an orphan at the age of one. Throughout his childhood, he was the poster child for mental and physical abuse by his foster parents. He put himself through Rindge Technical School in Cambridge, Massachusetts at the age of 16 then went to work as an apprentice patternmaker in the shipyards. He was enthralled with woodworking and started making beautiful furniture. At age 18, he crafted, from 55 pieces of Santo Domingo mahogany, a grandfather clock which can be seen in his home today.

Korczak never took an art or sculpture lesson. He studied the masters on his own and started working with plaster and clay. His first portrait was a marble tribute to Judge Frederick Pickering Cabot, a famous Boston juvenile judge who had mentored Korczak.

Upon moving to West Hartford, Connecticut, Korczak launched his career doing commissioned sculptures throughout New England and New York. At the 1939 New York World’s Fair, his Carrara marble portrait of Paderewski won first prize by popular vote.

During the summer of 1939, Gutzon Borglum asked Korczak to assist him at Mount Rushmore. Korczak became involved in a feud with Borglum’s son and was fired after a few months.

Because of the Paderewski (famous Polish pianist and patriot) sculpture and his work at Mount Rushmore, Lakota Chief Standing Bear wrote to him asking Korczak to create a memorial to American Indians. In his letter, he wrote, “My fellow chiefs and I would like the white man to know the red man has great heroes, also.”

The two met in 1940 at the Pine Ridge Reservation where Korczak learned about Crazy Horse and why the Indians picked that leader for the mountain carving. Standing Bear was a maternal cousin of Crazy Horse making it culturally appropriate for him to initiate such a memorial to his relative. The Lakota leaders believed it was an omen for Korczak to create the sculpture as he was born on September 6, 31 years to the day that Crazy Horse had died. Another reason was Crazy Horse had told his people that he would return to them in the stone. He often wore a protective stone talisman in his ear. That is shown on Korczak’s later models.

Korczak wanted the Memorial located in the Wyoming Tetons where the rock was better and it would be a distance from Mount Rushmore. Standing Bear wanted the memorial in the Black Hills since it was sacred territory for the Lakotas.

Returning to Connecticut, Korczak spent two years carving his 13-1/2-foot tall Noah Webster statue which he gifted to West Hartford. At age 34, he entered the army to fight in World War II. He was wounded upon landing at Omaha Beach. After the war, he accepted Standing Bear’s offer, turning down the government’s commission to build war memorials in Europe.

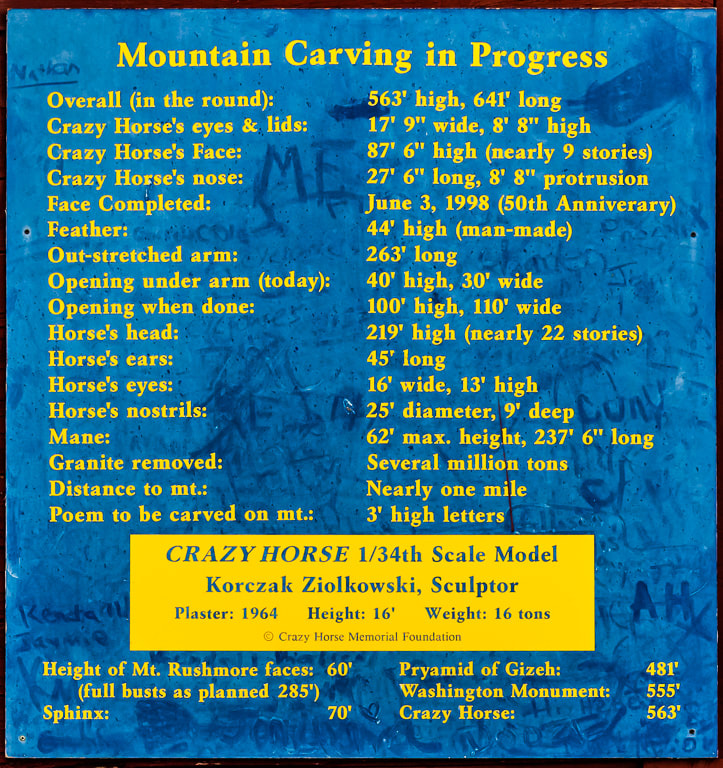

In 1946, the two decided to build the 600-foot memorial on Thunderhead Mountain. Arriving in the Black Hills on May 3, 1947, Korczak and Standing Bear decided in order to relate the story of the Indian people they needed to build the sculpture in the round rather than just the top 100 feet as Korczak had originally proposed. The finished sculpture would be 563 feet high and 641 feet long. To give some perspective, the heads on Mount Rushmore are 60 feet high. They agreed that Crazy Horse represented not one leader but the spirit of all Native Americans.

The memorial was dedicated June 3, 1948 with the first blast on the mountain. Crazy Horse never allowed a photograph of himself so no one knows exactly what he looked like. However, at that blast, Korczak had the opportunity to speak to five of the nine survivors at the Battle of Little Bighorn who knew Crazy Horse. They related information about him.

Korczak pledged, when he accepted the invitation of the Indian leaders, never to accept government financial aid and that the memorial would be a nonprofit educational and cultural humanitarian effort. It would tell the Indian story by collecting and preserving examples of their heritage. Eventually, the Memorial would benefit today’s Native Americans by creating a university.

He never accepted any government aid though offered $10 million on two separate occasions. He believed government would not complete the project or carry out its cultural and educational goals. He pointed out that Mount Rushmore’s presidents were to be full figures instead of just heads. In 1949, the nonprofit Crazy Horse Memorial Foundation® was established to support Korczak’s dream. At Crazy Horse, money was and still is raised through donations, admissions, and the gift shop.

Although he worked on the project for nearly 36 years, Korczak never received any salary. He died October 20, 1982 and is buried in a tomb that he and his sons blasted from a rock outcropping at the mountain’s base.

KORCZAK’S WORK ON CRAZY HORSE

When Korczak arrived at the site, no water, electricity, roads, or buildings existed. Just land and trees. He lived in a tent the first seven months while hand-building roads and a log cabin so he would have a place to live.

Work on the monument was slow and arduous as he labored tirelessly by himself. He used one small jackhammer to drill the holes, powered by an ancient gasoline-fueled compressor through a three-inch pipeline he laid up and across the mountain. He also improvised an aerial cable car to carry his equipment and dynamite.

With the blizzard of 1948-49, he soon learned that winter weather severely handicapped his project. Work at Crazy Horse was limited almost strictly to summers since the equipment would freeze during the winters.

He first worked on the mountain under a mining claim permit. In the early 1950's, the foundation acquired 328 acres around the memorial in a land exchange with the federal government. By logging nearby trees, Korczak installed, with Ruth’s help, a 741-foot staircase along the entire height of the mountain.

Slowly he built roads. In 1956, he installed his first road up the back of the mountain allowing him to put his first bulldozer on top. The next year, he constructed Avenue of the Chiefs, from Highway 16-385 to his studio-home. To supplement income, he operated a lumber mill. It took until 1966/67 to get electricity to the top of the mountain.

In the early 1970s, Korczak concentrated on blocking out the horse’s head. This involved blasting away the entire right side of the mountain. That work continued into the 1980s. Family members were enlisted to do drilling while Korczak did most of the bulldozing. His health problems involving his heart and several disc removals from his back hampered his effort as did limited finances. However, his dedication and determination never faltered.

RUTH ZIOLKOWSKI

Ruth was born Ruth Carolyn Ross on June 26, 1926 in West Hartford, Connecticut. At the age of 15, she was among a group of volunteers who helped raise money for the Noah Webster statue. She arrived in the Black Hills in 1947 as a volunteer on the Crazy Horse Memorial®, and in 1950, she and Korczak married. The Ziolkowski’s had ten children - five boys and five girls.

With so many children, Korczak moved a one-room schoolhouse to Crazy Horse, which several of his youngsters attended under a certified teacher. The boys helped their father on the mountain while the girls assisted in the Visitor Complex. All helped with the lumber mill, dairy farm, and other activities at Crazy Horse. Seven remained involved with the Crazy Horse project when Ruth was CEO.

Ruth oversaw the day-to-day operations in the early years of the Crazy Horse Memorial®. This included the dairy farm and lumber mill which were the only sources of income for the family and the carving. A major task was handling all purchases for Crazy Horse and the Ziolkowskis.

She and Korczak worked closely together. When he painted the outline of Crazy Horse on the mountain in 1951, she used binoculars from a mile away to guide him point to point which direction to draw. He used a four-inch brush and 176 gallons of paint to complete this, hanging on a rope above the treetops. They communicated via an army surplus phone.

That year, they prepared three books of comprehensive measurements so the work would continue no matter who was in charge. Ruth became the President and CEO of Crazy Horse when Korczak died. That was a position she maintained until her death.

Korczak had concentrated his efforts on the 219-foot high horse’s head. Ruth changed the focus to the 87.5-foot high face of Crazy Horse. She reasoned that Crazy Horse’s head was half the height of the horse so could show details sooner at a lower cost.

Because of her efforts, starting in 1987, the workers became involved with details as well as new techniques for measuring, drilling, explosives, engineering, and torching. They used the point system to transfer measurements from Korczak’s 1/34th scale model of the memorial to the mountain carving. Computers and a rotating measuring boom aided this effort. They also used a torch as a finish and channeling tool. In 1991, Crazy Horse’s eyes were opened. In June 1998, Crazy Horse’s face was completed and a dedication was held.

Under Ruth’s leadership, focus returned to the horse’s head. In 2007, philanthropist T. Denny Sanford of Sioux Falls, South Dakota announced the largest gift in the Memorial’s history - a $5 million matching challenge. For every dollar given for carving the horse’s head, Sanford has given a dollar. This has made the horse’s head close to completion. When that is done, workers will concentrate on Crazy Horse’s hand and arm.

Besides her role as CEO, Ruth expanded the public facilities. Her improvements include a 300-seat theater, a wing to The Indian Museum of North America®, expansions to the parking lot and viewing veranda, and the addition of gift shops, a restaurant, a library, a laser show, and more. She also added The Native American Educational and Cultural Center® and The Indian University of North America®. Ruth died in May 2014.

Four of the children are still involved. Monique Ziolkowski, Ruth’s daughter, became CEO of the mountain carving. Jadwiga, another daughter, is CEO of everything else. Adam runs the dairy farm while Mark is in charge of the stone quarry. Three of Monique’s nephews also work on projects. The current focus is on Crazy Horse’s left hand and arm, the top of his head, his hairline, and the horse’s mane.

CRAZY HORSE WELCOME CENTER

In front of the Center, you will find the Nature Gates. These are iron gates that Korczak and the Ziolkowski children decorated with the silhouettes of 219 animals (past and present) native to South Dakota.

Start your visit at the center. It’s the place to watch a 22-minute film about Crazy Horse titled Dynamite and Dream. You can also have your questions answered, obtain tickets for the bus tour, and see artifacts and art displayed from the Memorial’s collection.

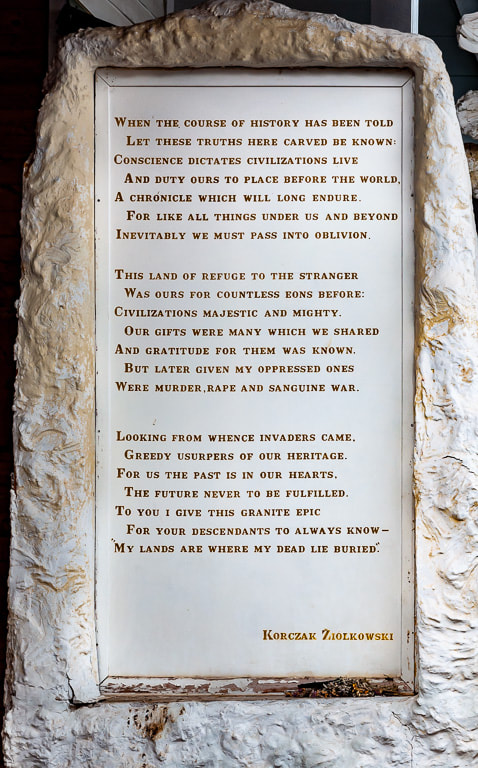

On the patio, note the large white model of what the monument will look like when it is completed. It is 1/34th of the size. Many wonder what Crazy Horse is pointing at with his left hand. He was asked by a cavalry soldier, “Where are your lands now?” Crazy Horse answered, “My lands are where my dead lie buried.”

At the end of the Center nearest the mountain, notice the Wall of Windows. It gives a wonderful view of the carving in progress. The Center adjoins the Indian Museum of North America® and gift shop.

THE INDIAN MUSEUM OF NORTH AMERICA®

You can easily spend an hour examining the art and artifacts displayed here. The collection started in 1965 with a donation by Charles Eder, a Hunkpapa Lakota from Montana. It includes moccasins, garments, hatchets, drums, and beadwork.

The museum collection contains more than 12,000 contemporary and historic items from pre-Columbian to contemporary times representing the diverse cultures, traditions, and heritage of native nations. Tribes are represented from the Alaska Inuits to the Florida Seminoles. Ninety percent of the artifacts have been donated, including many by Native Americans. Contributions to the museum are welcome today.

Some highlights are Chief Henry Standing Bear’s headdress, Korczak’s well-worn hat, and a statue of Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce. You’ll find kachinas, numerous beaded goods of all types, beautiful rugs, Inuit masks, Seminole dolls, and a case of prehistoric figures.

The flags of more than 125 Native American tribes are displayed. Visitors also see a collection of paintings by Andrew Standing Soldier and Hobart Keith portraying life in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Both were residents of the Pine Ridge Reservation. They also have a mannequin of a horse and an erected tipi.

Korczak and his family built the museum during the winter of 1972-73 when they could not work on the mountain due to weather conditions. It reveals his love of wood and natural lighting. The ponderosa pine was harvested and milled at the Memorial. In the early 1980s, Korczak planned new wings. After his death, Ruth, family members, and a small permanent staff added a second wing in 1983-84. This Mountain Museum wing helps explain the work behind the scenes.

THE MOUNTAIN CARVING GALLERY

This gallery depicts the story of how the mountain was carved. Visitors will see a half size replica of the wooden basket Korczak used to haul equipment and tools up the mountain. They’ll also see measuring tools used to carve Crazy Horse’s face, plasters of his face, and a detailed pictorial exhibit showing how his face was sculpted over the years. There are details how the Memorial is proceeding. Displays show how finished surface work is performed, how drilling is done, how feathering occurs, and about the ropes they use.

One highlight is the display of the letter Standing Bear wrote Korczak inviting him to create the Memorial. It includes photos of Standing Bear’s visit to Korczak’s home in Connecticut.

ZIOLKOWSKI HOME AND SCULPTOR STUDIO

You can visit the log cabin where Korczak and his family lived. It is still used for family functions. Korczak hand cut trees for the home using log beams that were 70 feet long. A 30-foot skylight into the home enabled him to see the mountain. Ruth did all of the peeling and chinking of the home’s logs.

The cabin is full of antiques from his Hartford, Connecticut residence as well as many of his sculptures. These include a Marie Antoinette mirror, Louis the 16th chairs, and a glass topped table Korczak created from a four legged piano. You will also see portraits of Ruth and Korczak. Among his exhibited sculptures are the Horse’s Head that he carved in nine days, Old Pagen, and the Polish Eagle.

Korczak and Ruth built a workshop and sun room in 1962 which you can tour today. A variety of wood, bronze, marble sculptures and casts are exhibited as well as displays tracing the Memorial’s history. You’ll also see the wooden toolbox that Korczak made when he was 18 years old.

Some unusual items are on display. One is a full-sized, original Concord stagecoach. Korczak acquired it in a trade for some of his work. Drums and costumes hanging in the workshop represent the Noah Webster Fife and Drum Corps. These young people, including his future wife, Ruth Ross, traveled from Connecticut to help with the beginning of the Memorial. You’ll also see a bronze of the carving of Standing Bear that Korczak gave to President John Kennedy in 1962.

In the area titled the Back Porch, you can see a wooden Crazy Horse that Korczak carved in 1952 of Ponderosa Pine. It was an early model for the Memorial where a half inch equaled one foot. You’ll also see photographs of the face from August 1993, July 1994, June 1995, and the Spring of 1998. A diorama depicts what the finished university will look like. Finally, a bin has rocks that have been blasted off the mountain. You are allowed to take some.

THE NATIVE AMERICAN EDUCATIONAL AND CULTURAL CENTER®

The Center is a great place to view Native American Artists in Residence creating handcrafts which they sell. During the summer season, it becomes an active marketplace. Sometimes storytelling, flute playing, song, and dance occur here and on the patio.

Last September when we visited, two craftsmen were displaying their goods. Tracy Harrison, an Oglala Sioux, was making dreamcatchers while Dawn Arkinson, Red Cloud, was making pendant/earring sets. They were receptive to answering questions about their work.

On the Center’s lower level, visitors find prints by frontier photographer Edward Curtis taken around the end of the 19th century. They focus on the American West and Native American peoples.

One wall of the lower level houses the Exhibit of the American Bison. It traces the history of bison from their prehistoric beginnings to their near extinction. It relates the story of those who helped save the remaining bison at the end of the 1800s and the animal’s significance to Native Americans.

THE INDIAN UNIVERSITY OF NORTH AMERICA®

Educational efforts started in 1978 with a single college scholarship of $250. Now the cumulative total awarded to Native American students attending colleges, universities, vocational- technical schools, or tribal colleges in South Dakota exceeds two million. Crazy Horse Memorial® is not involved in the selection process. Funds are distributed and recipients selected by the various schools.

Since 1996, college-level courses have been held in the Native American Educational and Cultural Center® and the Welcome Center. The Indian University of North America® opened June 7, 2010 with the debut of the Student Living and Learning Center. It is a classroom building and residence hall for up to 40 students with apartments for adult mentors. It was made possible by a $2.5 million grant from T. Denny Sanford of Sioux Falls. Muffy and Paul Christen of Huron, South Dakota established a $5 million endowment that pays for the school’s operating costs.

The University is a satellite campus of the University of South Dakota which is in Vermillion, South Dakota. USD ensures academic standards, designs the curriculum, selects the faculty, and recruits the students.

The 10-week program involves college preparation classes and freshman-level courses in algebra, English, speech, history, finance, and American Indian studies. Students can obtain paid internships to fund their share of education and living costs as well as learn new job skills.

They receive an education, books, a computer, and room and board. There are 32 students to a class. As it is only a semester long, it is not a degree program. They earn up to 12 college credits that can be transferred to other schools as they further their education. The program, open to Native Americans and nonnatives, has been completed by about 300.

LAUGHING WATER RESTAURANT

You won’t have to go off campus to find something to eat. This restaurant specializes in Native American dishes as well as comfort food. No reservations are needed and coffee is free.

You might want to try their Native American Taco. It’s homemade Indian fry bread topped with taco meat, refried beans, lettuce, tomatoes, cheese, onions, salsa, and sour cream. Their tatanka stew is made from Black Hills buffalo that’s slow cooked with carrots, sweet peas, green onions, pearl onions, and tomatoes. It’s served with Indian fry bread. For dessert, check out their fry bread topped with a warm berry sauce, cinnamon, or honey.

Look for the knife collection in the dining hall. Senator Ben Nighthorse Campbell made the more than 20 knives that are in the case. He is a Cheyenne-American who was a United States senator from Colorado from 1993 to 2005.

LASER LIGHTS SHOW

From Memorial Day weekend through Native American Day in mid-October, visitors should complete their visit to the Memorial by watching the multimedia laser show “Legends in Light.” It relates the story of Native Americans - their heritage, culture, and contributions. It’s a combination of laser beams, colorful animations, and sound effects choreographed to music displayed on a 500-foot screen. The best place to watch it is from the parking lot. Starting times vary so check at the Welcome Center.

BUS TOUR

A 25-minute bus tour is given to the base of the mountain. Passengers can unload so they can take close-up photographs of the Memorial. Visitors learn the history of the Memorial and have the dairy farm, Korczak’s tomb, and Zeus, the bulldozer he used, pointed out to them. The fee is $4 per person. It’s free for those ages six and under.

SPECIAL EVENTS

Throughout the year, special events take place from night blasts to Native Americans’ Day on the second Monday in October, and Volksmarches in June and September. The next night blast will be September 6 to honor the anniversaries of the 1877 death of Crazy Horse and the 1908 birth of Korczak. The 7th annual fall Volksmarch occurs on September 29. To learn more about these, visit the Memorial’s web site.

.

DETAILS

The Crazy Horse Memorial® address is 12151 Avenue of the Chiefs, Crazy Horse, South Dakota. Their telephone number is (605) 673-4681. The Memorial is open year- round from 7:00 a.m. to dark. Admission fees are $30 per car for more than two people, $24 for two people in a car, $12 per person, and $7 per person on motorcycle or bicycle. Native Americans, children under the age of six, and military with active-duty ID are admitted free.

Located approximately 17 miles from Mount Rushmore, near Custer City, visitors find the largest sculpture on Earth being created on Thunderhead Mountain. It’s the Crazy Horse Memorial® which has been under construction since 1948.

The monument depicts the Oglala Lakota warrior Crazy Horse sitting on a horse and pointing to his lands in the distance. It was commissioned by Henry Standing Bear, a Lakota elder, to be sculpted by Korczak Ziolkowski. When Korczak died in 1982, his wife Ruth headed the project until her death in 2014. The second and third generations of this family now carry on this work. No date has been set for the memorial’s completion.

The Crazy Horse Memorial Foundation®, a nonprofit organization, operates Crazy Horse, supervising its continuing progress. However, it is concerned with more than just this extensive sculpture. Its mission is to protect and preserve the culture, tradition, and living heritage of the North American Indians.

The Foundation’s Indian Museum of North America® and its The Native American Educational and Cultural Center® act as repositories for artifacts, crafts, and arts representing more than 50 tribes. The Indian University of North America® provides courses. In the future, it hopes to open a medical training center for American Indians. All of these are on the monument’s campus in addition to a Welcome Center, the Ziolkowski home, Korczak’s sculptor studio, and various other museums.

CRAZY HORSE

Crazy Horse was not a chief but a highly regarded warrior who was ferocious in battle. He was recognized by his people as a leader committed to preserving the traditions and values of the Lakota way of life.

Before he was thirteen, he stole horses from the Crow Indians and led his first war party before turning twenty. He was instrumental in the 1865-68 war that Oglala chief Red Cloud led against Wyoming’s settlers. In 1867, Crazy Horse played a key role in destroying William J. Fetterman’s brigade at Fort Kearny, Nebraska.

Crazy Horse provided resistance to American encroachment on Lakota lands. In 1873, he attacked a surveying party sent into the Black Hills by General George Armstrong Custer. When all Lakota bands were ordered by the War Department onto reservations in 1876, Crazy Horse again led the fight.

Due to his first wife being Cheyenne, he allied with the Cheyenne. In June 17, 1876, he gathered together a force of 1,200 Oglala and Cheyenne at his village. He turned back General George Crook, who had tried to advance to Sitting Bull’s encampment on the Little Bighorn.

On June 25, 1876, Crazy Horse’s force joined with Sitting Bull to destroy Custer’s Seventh Cavalry at the Battle of Little Bighorn. While Chief Gall and his Hunkpapa warriors charged from the south and east, Crazy Horse’s braves flanked the cavalry from the north and west.

After that battle, Gall and Sitting Bull left for Canada. However, Crazy Horse continued to harass the United States Army. He battled General Nelson Miles during the winter of 1876-77.

When Crazy Horse left the reservation without authorization to take his sick wife to her parents, General Crook arrested him and took him to Fort Robinson, Nebraska on May 5, 1877. Crazy Horse struggled against being taken to a guardhouse. While his arms were held by one of the arresting officers, a soldier ran him through with a bayonet. He died on May 6, 1877.

KORCZAK ZIOLKOWSKI

Visitors to the memorial can learn about Korczak’s story while visiting his log studio-home, workshop, and sculptural galleries at Crazy Horse.

Born in Boston of Polish descent, Korczak became an orphan at the age of one. Throughout his childhood, he was the poster child for mental and physical abuse by his foster parents. He put himself through Rindge Technical School in Cambridge, Massachusetts at the age of 16 then went to work as an apprentice patternmaker in the shipyards. He was enthralled with woodworking and started making beautiful furniture. At age 18, he crafted, from 55 pieces of Santo Domingo mahogany, a grandfather clock which can be seen in his home today.

Korczak never took an art or sculpture lesson. He studied the masters on his own and started working with plaster and clay. His first portrait was a marble tribute to Judge Frederick Pickering Cabot, a famous Boston juvenile judge who had mentored Korczak.

Upon moving to West Hartford, Connecticut, Korczak launched his career doing commissioned sculptures throughout New England and New York. At the 1939 New York World’s Fair, his Carrara marble portrait of Paderewski won first prize by popular vote.

During the summer of 1939, Gutzon Borglum asked Korczak to assist him at Mount Rushmore. Korczak became involved in a feud with Borglum’s son and was fired after a few months.

Because of the Paderewski (famous Polish pianist and patriot) sculpture and his work at Mount Rushmore, Lakota Chief Standing Bear wrote to him asking Korczak to create a memorial to American Indians. In his letter, he wrote, “My fellow chiefs and I would like the white man to know the red man has great heroes, also.”

The two met in 1940 at the Pine Ridge Reservation where Korczak learned about Crazy Horse and why the Indians picked that leader for the mountain carving. Standing Bear was a maternal cousin of Crazy Horse making it culturally appropriate for him to initiate such a memorial to his relative. The Lakota leaders believed it was an omen for Korczak to create the sculpture as he was born on September 6, 31 years to the day that Crazy Horse had died. Another reason was Crazy Horse had told his people that he would return to them in the stone. He often wore a protective stone talisman in his ear. That is shown on Korczak’s later models.

Korczak wanted the Memorial located in the Wyoming Tetons where the rock was better and it would be a distance from Mount Rushmore. Standing Bear wanted the memorial in the Black Hills since it was sacred territory for the Lakotas.

Returning to Connecticut, Korczak spent two years carving his 13-1/2-foot tall Noah Webster statue which he gifted to West Hartford. At age 34, he entered the army to fight in World War II. He was wounded upon landing at Omaha Beach. After the war, he accepted Standing Bear’s offer, turning down the government’s commission to build war memorials in Europe.

In 1946, the two decided to build the 600-foot memorial on Thunderhead Mountain. Arriving in the Black Hills on May 3, 1947, Korczak and Standing Bear decided in order to relate the story of the Indian people they needed to build the sculpture in the round rather than just the top 100 feet as Korczak had originally proposed. The finished sculpture would be 563 feet high and 641 feet long. To give some perspective, the heads on Mount Rushmore are 60 feet high. They agreed that Crazy Horse represented not one leader but the spirit of all Native Americans.

The memorial was dedicated June 3, 1948 with the first blast on the mountain. Crazy Horse never allowed a photograph of himself so no one knows exactly what he looked like. However, at that blast, Korczak had the opportunity to speak to five of the nine survivors at the Battle of Little Bighorn who knew Crazy Horse. They related information about him.

Korczak pledged, when he accepted the invitation of the Indian leaders, never to accept government financial aid and that the memorial would be a nonprofit educational and cultural humanitarian effort. It would tell the Indian story by collecting and preserving examples of their heritage. Eventually, the Memorial would benefit today’s Native Americans by creating a university.

He never accepted any government aid though offered $10 million on two separate occasions. He believed government would not complete the project or carry out its cultural and educational goals. He pointed out that Mount Rushmore’s presidents were to be full figures instead of just heads. In 1949, the nonprofit Crazy Horse Memorial Foundation® was established to support Korczak’s dream. At Crazy Horse, money was and still is raised through donations, admissions, and the gift shop.

Although he worked on the project for nearly 36 years, Korczak never received any salary. He died October 20, 1982 and is buried in a tomb that he and his sons blasted from a rock outcropping at the mountain’s base.

KORCZAK’S WORK ON CRAZY HORSE

When Korczak arrived at the site, no water, electricity, roads, or buildings existed. Just land and trees. He lived in a tent the first seven months while hand-building roads and a log cabin so he would have a place to live.

Work on the monument was slow and arduous as he labored tirelessly by himself. He used one small jackhammer to drill the holes, powered by an ancient gasoline-fueled compressor through a three-inch pipeline he laid up and across the mountain. He also improvised an aerial cable car to carry his equipment and dynamite.

With the blizzard of 1948-49, he soon learned that winter weather severely handicapped his project. Work at Crazy Horse was limited almost strictly to summers since the equipment would freeze during the winters.

He first worked on the mountain under a mining claim permit. In the early 1950's, the foundation acquired 328 acres around the memorial in a land exchange with the federal government. By logging nearby trees, Korczak installed, with Ruth’s help, a 741-foot staircase along the entire height of the mountain.

Slowly he built roads. In 1956, he installed his first road up the back of the mountain allowing him to put his first bulldozer on top. The next year, he constructed Avenue of the Chiefs, from Highway 16-385 to his studio-home. To supplement income, he operated a lumber mill. It took until 1966/67 to get electricity to the top of the mountain.

In the early 1970s, Korczak concentrated on blocking out the horse’s head. This involved blasting away the entire right side of the mountain. That work continued into the 1980s. Family members were enlisted to do drilling while Korczak did most of the bulldozing. His health problems involving his heart and several disc removals from his back hampered his effort as did limited finances. However, his dedication and determination never faltered.

RUTH ZIOLKOWSKI

Ruth was born Ruth Carolyn Ross on June 26, 1926 in West Hartford, Connecticut. At the age of 15, she was among a group of volunteers who helped raise money for the Noah Webster statue. She arrived in the Black Hills in 1947 as a volunteer on the Crazy Horse Memorial®, and in 1950, she and Korczak married. The Ziolkowski’s had ten children - five boys and five girls.

With so many children, Korczak moved a one-room schoolhouse to Crazy Horse, which several of his youngsters attended under a certified teacher. The boys helped their father on the mountain while the girls assisted in the Visitor Complex. All helped with the lumber mill, dairy farm, and other activities at Crazy Horse. Seven remained involved with the Crazy Horse project when Ruth was CEO.

Ruth oversaw the day-to-day operations in the early years of the Crazy Horse Memorial®. This included the dairy farm and lumber mill which were the only sources of income for the family and the carving. A major task was handling all purchases for Crazy Horse and the Ziolkowskis.

She and Korczak worked closely together. When he painted the outline of Crazy Horse on the mountain in 1951, she used binoculars from a mile away to guide him point to point which direction to draw. He used a four-inch brush and 176 gallons of paint to complete this, hanging on a rope above the treetops. They communicated via an army surplus phone.

That year, they prepared three books of comprehensive measurements so the work would continue no matter who was in charge. Ruth became the President and CEO of Crazy Horse when Korczak died. That was a position she maintained until her death.

Korczak had concentrated his efforts on the 219-foot high horse’s head. Ruth changed the focus to the 87.5-foot high face of Crazy Horse. She reasoned that Crazy Horse’s head was half the height of the horse so could show details sooner at a lower cost.

Because of her efforts, starting in 1987, the workers became involved with details as well as new techniques for measuring, drilling, explosives, engineering, and torching. They used the point system to transfer measurements from Korczak’s 1/34th scale model of the memorial to the mountain carving. Computers and a rotating measuring boom aided this effort. They also used a torch as a finish and channeling tool. In 1991, Crazy Horse’s eyes were opened. In June 1998, Crazy Horse’s face was completed and a dedication was held.

Under Ruth’s leadership, focus returned to the horse’s head. In 2007, philanthropist T. Denny Sanford of Sioux Falls, South Dakota announced the largest gift in the Memorial’s history - a $5 million matching challenge. For every dollar given for carving the horse’s head, Sanford has given a dollar. This has made the horse’s head close to completion. When that is done, workers will concentrate on Crazy Horse’s hand and arm.

Besides her role as CEO, Ruth expanded the public facilities. Her improvements include a 300-seat theater, a wing to The Indian Museum of North America®, expansions to the parking lot and viewing veranda, and the addition of gift shops, a restaurant, a library, a laser show, and more. She also added The Native American Educational and Cultural Center® and The Indian University of North America®. Ruth died in May 2014.

Four of the children are still involved. Monique Ziolkowski, Ruth’s daughter, became CEO of the mountain carving. Jadwiga, another daughter, is CEO of everything else. Adam runs the dairy farm while Mark is in charge of the stone quarry. Three of Monique’s nephews also work on projects. The current focus is on Crazy Horse’s left hand and arm, the top of his head, his hairline, and the horse’s mane.

CRAZY HORSE WELCOME CENTER

In front of the Center, you will find the Nature Gates. These are iron gates that Korczak and the Ziolkowski children decorated with the silhouettes of 219 animals (past and present) native to South Dakota.

Start your visit at the center. It’s the place to watch a 22-minute film about Crazy Horse titled Dynamite and Dream. You can also have your questions answered, obtain tickets for the bus tour, and see artifacts and art displayed from the Memorial’s collection.

On the patio, note the large white model of what the monument will look like when it is completed. It is 1/34th of the size. Many wonder what Crazy Horse is pointing at with his left hand. He was asked by a cavalry soldier, “Where are your lands now?” Crazy Horse answered, “My lands are where my dead lie buried.”

At the end of the Center nearest the mountain, notice the Wall of Windows. It gives a wonderful view of the carving in progress. The Center adjoins the Indian Museum of North America® and gift shop.

THE INDIAN MUSEUM OF NORTH AMERICA®

You can easily spend an hour examining the art and artifacts displayed here. The collection started in 1965 with a donation by Charles Eder, a Hunkpapa Lakota from Montana. It includes moccasins, garments, hatchets, drums, and beadwork.

The museum collection contains more than 12,000 contemporary and historic items from pre-Columbian to contemporary times representing the diverse cultures, traditions, and heritage of native nations. Tribes are represented from the Alaska Inuits to the Florida Seminoles. Ninety percent of the artifacts have been donated, including many by Native Americans. Contributions to the museum are welcome today.

Some highlights are Chief Henry Standing Bear’s headdress, Korczak’s well-worn hat, and a statue of Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce. You’ll find kachinas, numerous beaded goods of all types, beautiful rugs, Inuit masks, Seminole dolls, and a case of prehistoric figures.

The flags of more than 125 Native American tribes are displayed. Visitors also see a collection of paintings by Andrew Standing Soldier and Hobart Keith portraying life in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Both were residents of the Pine Ridge Reservation. They also have a mannequin of a horse and an erected tipi.

Korczak and his family built the museum during the winter of 1972-73 when they could not work on the mountain due to weather conditions. It reveals his love of wood and natural lighting. The ponderosa pine was harvested and milled at the Memorial. In the early 1980s, Korczak planned new wings. After his death, Ruth, family members, and a small permanent staff added a second wing in 1983-84. This Mountain Museum wing helps explain the work behind the scenes.

THE MOUNTAIN CARVING GALLERY

This gallery depicts the story of how the mountain was carved. Visitors will see a half size replica of the wooden basket Korczak used to haul equipment and tools up the mountain. They’ll also see measuring tools used to carve Crazy Horse’s face, plasters of his face, and a detailed pictorial exhibit showing how his face was sculpted over the years. There are details how the Memorial is proceeding. Displays show how finished surface work is performed, how drilling is done, how feathering occurs, and about the ropes they use.

One highlight is the display of the letter Standing Bear wrote Korczak inviting him to create the Memorial. It includes photos of Standing Bear’s visit to Korczak’s home in Connecticut.

ZIOLKOWSKI HOME AND SCULPTOR STUDIO

You can visit the log cabin where Korczak and his family lived. It is still used for family functions. Korczak hand cut trees for the home using log beams that were 70 feet long. A 30-foot skylight into the home enabled him to see the mountain. Ruth did all of the peeling and chinking of the home’s logs.

The cabin is full of antiques from his Hartford, Connecticut residence as well as many of his sculptures. These include a Marie Antoinette mirror, Louis the 16th chairs, and a glass topped table Korczak created from a four legged piano. You will also see portraits of Ruth and Korczak. Among his exhibited sculptures are the Horse’s Head that he carved in nine days, Old Pagen, and the Polish Eagle.

Korczak and Ruth built a workshop and sun room in 1962 which you can tour today. A variety of wood, bronze, marble sculptures and casts are exhibited as well as displays tracing the Memorial’s history. You’ll also see the wooden toolbox that Korczak made when he was 18 years old.

Some unusual items are on display. One is a full-sized, original Concord stagecoach. Korczak acquired it in a trade for some of his work. Drums and costumes hanging in the workshop represent the Noah Webster Fife and Drum Corps. These young people, including his future wife, Ruth Ross, traveled from Connecticut to help with the beginning of the Memorial. You’ll also see a bronze of the carving of Standing Bear that Korczak gave to President John Kennedy in 1962.

In the area titled the Back Porch, you can see a wooden Crazy Horse that Korczak carved in 1952 of Ponderosa Pine. It was an early model for the Memorial where a half inch equaled one foot. You’ll also see photographs of the face from August 1993, July 1994, June 1995, and the Spring of 1998. A diorama depicts what the finished university will look like. Finally, a bin has rocks that have been blasted off the mountain. You are allowed to take some.

THE NATIVE AMERICAN EDUCATIONAL AND CULTURAL CENTER®

The Center is a great place to view Native American Artists in Residence creating handcrafts which they sell. During the summer season, it becomes an active marketplace. Sometimes storytelling, flute playing, song, and dance occur here and on the patio.

Last September when we visited, two craftsmen were displaying their goods. Tracy Harrison, an Oglala Sioux, was making dreamcatchers while Dawn Arkinson, Red Cloud, was making pendant/earring sets. They were receptive to answering questions about their work.

On the Center’s lower level, visitors find prints by frontier photographer Edward Curtis taken around the end of the 19th century. They focus on the American West and Native American peoples.

One wall of the lower level houses the Exhibit of the American Bison. It traces the history of bison from their prehistoric beginnings to their near extinction. It relates the story of those who helped save the remaining bison at the end of the 1800s and the animal’s significance to Native Americans.

THE INDIAN UNIVERSITY OF NORTH AMERICA®

Educational efforts started in 1978 with a single college scholarship of $250. Now the cumulative total awarded to Native American students attending colleges, universities, vocational- technical schools, or tribal colleges in South Dakota exceeds two million. Crazy Horse Memorial® is not involved in the selection process. Funds are distributed and recipients selected by the various schools.

Since 1996, college-level courses have been held in the Native American Educational and Cultural Center® and the Welcome Center. The Indian University of North America® opened June 7, 2010 with the debut of the Student Living and Learning Center. It is a classroom building and residence hall for up to 40 students with apartments for adult mentors. It was made possible by a $2.5 million grant from T. Denny Sanford of Sioux Falls. Muffy and Paul Christen of Huron, South Dakota established a $5 million endowment that pays for the school’s operating costs.

The University is a satellite campus of the University of South Dakota which is in Vermillion, South Dakota. USD ensures academic standards, designs the curriculum, selects the faculty, and recruits the students.

The 10-week program involves college preparation classes and freshman-level courses in algebra, English, speech, history, finance, and American Indian studies. Students can obtain paid internships to fund their share of education and living costs as well as learn new job skills.

They receive an education, books, a computer, and room and board. There are 32 students to a class. As it is only a semester long, it is not a degree program. They earn up to 12 college credits that can be transferred to other schools as they further their education. The program, open to Native Americans and nonnatives, has been completed by about 300.

LAUGHING WATER RESTAURANT

You won’t have to go off campus to find something to eat. This restaurant specializes in Native American dishes as well as comfort food. No reservations are needed and coffee is free.

You might want to try their Native American Taco. It’s homemade Indian fry bread topped with taco meat, refried beans, lettuce, tomatoes, cheese, onions, salsa, and sour cream. Their tatanka stew is made from Black Hills buffalo that’s slow cooked with carrots, sweet peas, green onions, pearl onions, and tomatoes. It’s served with Indian fry bread. For dessert, check out their fry bread topped with a warm berry sauce, cinnamon, or honey.

Look for the knife collection in the dining hall. Senator Ben Nighthorse Campbell made the more than 20 knives that are in the case. He is a Cheyenne-American who was a United States senator from Colorado from 1993 to 2005.

LASER LIGHTS SHOW

From Memorial Day weekend through Native American Day in mid-October, visitors should complete their visit to the Memorial by watching the multimedia laser show “Legends in Light.” It relates the story of Native Americans - their heritage, culture, and contributions. It’s a combination of laser beams, colorful animations, and sound effects choreographed to music displayed on a 500-foot screen. The best place to watch it is from the parking lot. Starting times vary so check at the Welcome Center.

BUS TOUR

A 25-minute bus tour is given to the base of the mountain. Passengers can unload so they can take close-up photographs of the Memorial. Visitors learn the history of the Memorial and have the dairy farm, Korczak’s tomb, and Zeus, the bulldozer he used, pointed out to them. The fee is $4 per person. It’s free for those ages six and under.

SPECIAL EVENTS

Throughout the year, special events take place from night blasts to Native Americans’ Day on the second Monday in October, and Volksmarches in June and September. The next night blast will be September 6 to honor the anniversaries of the 1877 death of Crazy Horse and the 1908 birth of Korczak. The 7th annual fall Volksmarch occurs on September 29. To learn more about these, visit the Memorial’s web site.

.

DETAILS

The Crazy Horse Memorial® address is 12151 Avenue of the Chiefs, Crazy Horse, South Dakota. Their telephone number is (605) 673-4681. The Memorial is open year- round from 7:00 a.m. to dark. Admission fees are $30 per car for more than two people, $24 for two people in a car, $12 per person, and $7 per person on motorcycle or bicycle. Native Americans, children under the age of six, and military with active-duty ID are admitted free.

Crazy Horse from on Top of Mountain - 1995

Working on Crazy Horse Memorial - 2018

Crazy Horse Memorial - Close Up 1995

Crazy Horse Memorial - Close Up 2018

Shot of Whole Mountain - 2018

The Nature Gate in Front of the Welcome Center

Crazy Horse Memorial Welcome Center

Sign Near the Model Giving Statistics About the Memorial

1/34th Size Model of Crazy Horse, Looking Towards the Real Memorial

The Model on the Patio Draws Much Admiration

Sign on the Model

Laughing Water Restaurant

We Met in 2018 With Zita Ziolkowski, Korczak's Daughter, CEO of All but the Carving at Crazy Horse Memorial

Native American Performer on the Patio

Kwatiutl Nation Art - Typical of What You See in Alaska

Seminole Dolls

Horse Covered With Beaded Artwork in the Center of One of the Galleries

Beaded Pipe Bag, Moccasins, and Headband

Kachina Dolls

Chief Standing Bear's Headdress

Korczak's Well Worn Hat

Statue and Portraits of Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce

Drills in the Mountain Carving Gallery

Original Compressor Korczak Used Can Still Be Seen at the Memorial

Interior of Ruth and Korzcak's Home

Portrait of Korczak Ziolokowski

Portrait of Ruth Ziolkowski in Her Home

We Met Ruth Zolkowski in 1995

Korczak's Sculptor's Studio and Workshop

Some of Korczak's Many Sculptures

The Self Portrait Korzcak Sculpted

Original Concord Stagecoach That Korczak Acquired in a Trade for Some of His Work

Corps Volunteers Helped with the Beginning of the Memorial

Wooden Crazy Horse Korczak Carved from Pine in 1952 - Found on the Back Porch

You Find Native American Artists Like Dawn Arkinson Selling Her Handmade Pendant and Earring Sets

Crazy Horse Memorial Lit Up at Night