Hello Everyone,

Leadville is highly regarded for its historical tourism. Driving the 20- square-mile Route of the Silver Kings and exploring the National Mining Hall of Fame and Museum are worthwhile ways to further discover Leadville’s mining heritage.

ROUTE OF THE SILVER KINGS

The Route of the Silver Kings consists of interconnected roads. It takes a couple of hours to see and covers ghost towns, mines, a smelter, and a power plant. You’ll be driving on public dirt roads, but the mines are on private property, so it’s necessary to respect the “No Trespassing” signs. You aren’t allowed to enter any of the mine shafts or tunnels. Rock collecting and treasure hunting are prohibited. Taking a camera pays off since you will encounter many good photographic opportunities.

To fully enjoy your drive, you can obtain the brochure The Route of the Silver Kings from the Leadville/Lake County Visitor Center located at 809 Harrison Avenue. The brochure has a map that makes the combined two routes easier to follow. The Center is also a great stop to pick up information about other area places to visit.

To reach Stop #1, start your self guided driving tour at Monroe Street and Harrison Avenue. Continuing East, the first route takes you from the first to the fourth point. The second part of your drive starts on 7th Street on Harrison Avenue. It contains the other 10 stops.

Look for the 14 numbered signs, each indicating a point of interest. Be aware that where the brochure indicates mileage, such as 1.1 miles to the power plant, then A.Y. and Minnie mine 2.0 miles on the right, you measure from the beginning of each of the two routes. In this case, you travel to the second point 2.0 miles total. It is not the distance between points. This can be confusing so it’s very important to look for the numbered signs indicating a stop.

Stop #1 is the Harrison Reduction Works. These were one of 17 area smelters operating between 1879 and 1960. At the Harrison, they removed the silver from lead carbonate ore.

Stop #2 are the Yak Tunnel and the Power Plant. A steam powered generating plant existed in the red brick building. It provided electricity for the nearby mines. The four-mile Yak tunnel, built between 1895 and 1923, drained water and transported ore from the mines in the southern part of the district.

Stop #3 are Meyer Guggenheim’s A.Y. and Minnie Mines. They received their name because they were originally discovered by A.Y. Corman and his wife, Minnie. These were the foundation of the Guggenheim fortune. These two mines turned a profit of $2,000 a day and kept that up for a decade. Unfortunately his son, Benjamin, who was watching these mines for his father drowned, at age 46, in the sinking of the Titanic.

Stop #4 is Oro City (a mile northeast of Leadville). It’s where Abe Lee discovered placer gold in 1860, and the site of the single richest, placer gold strike in the entire Pikes Peak rush. In seven years, miners washed ten tons of gold, worth more than $5 million, from California Gulch. Oro City reached a peak population of 10,000. It nearly disappeared when the gold depleted until the silver boom in 1874. By 1890, only 222 people occupied this site. Today no structures remain standing, but you can see foundations and piles of gravel.

Stop #5 is where the town of Adelaide Park existed. The town started to form in 1876, around the Adelaide Mine, and by 1879 had a population of more than 1,000. Later, approximately 2,500 people lived here, and it housed 28 businesses. The town discontinued the post office in 1880. Today, nothing remains except for a few foundations.

Stop #6 is the Mikado or Gallagher Shaft. This mine, in 1887, employed 120 men. The ghosts of three of the five miners killed in the Mikado were supposed to wander in spirit form until the mid 1890's. Many miners quit their job as a result of these haunts. Today, only decaying timbers and the mine dumps remain. It produced lead-zinc sulphide and zinc carbonate at the rate of 150 tons a day.

Stop #7 is Finn Town. It was first settled by miners from England. In the 1890's large numbers of Scandinavians moved to Finn Town. They had stores, saloons, and a sauna.

This is also the location of the head frame of the Robert Emmet Mine. It was a lead-zinc and silver producer. During the miners’ strike of 1896-1897, a battle occurred between the strikers and mine guards here.

The strike closed 90% of the mines when miners sought a pay of $3 a day from the $2.50 they were reduced to during the 1893 Silver Panic. Mine owners, like Tabor, brought in the state militia which didn’t help the situation. Six months later the miners returned to work without a pay increase. The strike ended March 9, 1897. Many of the area mines closed and never reopened because, during the strike, the unpumped water accumulated and had carried large amounts of sand into the shafts sealing the mines.

Also at this stop, you’ll find the site of the Wolftone Mine, one of the Guggenheim properties in the late 1890s. In 1910, Samuel D. Nicholson, the mine manager, found a rich source of zinc. On January 11, 1911, to celebrate, he had an elaborate party for more than 250 people underground.

Sleighs provided the transportation from Tabor’s Grand Hotel to the banquet. As visitors drove by, the other mines, large American flags and mine whistles saluted them.

After touring the mine and its facilities, only six persons, at a time, rode the cage down to the 1,000 foot level. They were taken along a 75-foot dirt hallway, that was well lit with electric fixtures, to a banquet room - 110 feet long, 25 feet wide, and 10 feet high. Management had removed a total of 220 cubic feet of rock, $150,000 in minerals, to create this room. Colored bulbs projected hues on the rock and dirt walls. Bouquets and flower arrangements decorated two 100-foot tables.

Present at the catered dinner were two men playing bagpipes in tradition with the 152nd Anniversary of Scottish poet, Bobbie Burns. A six-piece orchestra also performed. After the party, the banquet room remained open to citizens, including tours by school children, for several days. On January 29, management removed the decorations and the mine resumed normal operations.

The discovery eventually led to the construction of the Western Zinc Oxide Smelting Company

Stop #8 is the location of wooden cribbing marking the site of the Coronado Mine. On September 21, 1896, the striking miners set the surface buildings on fire. The fire killed three men including a Leadville fireman, who was shot while turning on water to extinguish the flames.

Stop #9 is Fryer Hill, named after George Fryer, who staked the New Discovery claim in 1878. This was the location of three silver producing mines. It was the home of the Little Pittsburg where Horace Tabor grubstaked August Rische and George Hook in 1878 in exchange for one-third interest. It yielded $8,000 a week. Within a year, he sold it for one million dollars.

Another is the Chrysolite Shaft which paid off big for Tabor. It was salted by “Chicken Bill” Lovell with stolen, high grade ore to attract a high price. Tabor purchased it, dug down another 25 feet, and then sold it after it produced $1.5 million dollars. He later sold the mine to others including Marshall Field of Chicago merchandising fame.

The Robert E. Lee Mine produced $3 million by 1882. It was called “The Silver Vault” of Fryer Hill.

Take time at this stop to notice the head frame of the Wright Shaft for the Denver City Mine. Its A-shape was a prominent feature of the tin mine head frames found in Cornwall, England. The shaft runs 320 feet deep.

Stop #10 is Evansville, a small mining camp in 1880, where families of miners employed in nearby mines lived. It reached a peak population of 1,000 in the 1890's but disappeared by the 1930's Depression. You can still spot some of the cabins’ stone foundations.

Stop #11 is the Resurrection Mine No. 2 Shaft which operated until a fire destroyed its surface plant in 1956. Miners extracted lead, zinc, gold, and silver from this 1,000 foot shaft then sent the minerals through the connecting Yak Tunnel to the California Gulch mill. Nearby, you’ll find the tall, modern head frame and other buildings of the Diamond Shaft. Until it closed in 1988, its primary product was gold.

Stop #12 was first called “South Evans” but was later named Stumptown. The settlement began in 1879 with the discovery of lead carbonate ores in the Little Ellen Mine. It was largely abandoned in the late 1930's. You’ll see the remains of several buildings at this stop.

It was primarily a residential town with a few saloons. Houses were small and none had indoor plumbing. Water for cooking and bathing came from the town pump. Margaret “Molly” Brown arrived in the early 1880s and lived in Stumptown for a year, as a young bride, before residing in Leadville.

Stop #13 is the Ibex Mine Complex, consisting of the town of Ibex and five shafts operated by Ibex Mining Company. The number one shaft was known as the Little Johny Mine. It was here that J.J. Brown, Margaret’s husband, the superintendent of all the Ibex properties, devised a way to overcome drainage problems at this site in the early 1890s. He was rewarded with 1/8th of the interest in the mine which had vast quantities of high-grade copper and gold. This accounted for the Browns’ fortune.

If you have a four-wheel drive on your vehicle, then you may want to take in stop #14. You have to travel up a steep hill, not recommended for your normal family car, to the Venir Shaft where gold was produced until the 1940's. We felt that because of its isolation, it was the best preserved area on the route. You will also have excellent views of Turquoise Lake, and Colorado’s tallest mountains, Mt. Elbert and Mt. Massive.

NATIONAL MINING HALL OF FAME AND MUSEUM

Plan on spending a minimum of three to four hours at this 20-room museum, in addition to open areas and hallways, which once housed Leadville’s junior high and then senior high. Opened to the public in 1987, it represents mining from all over the world. It is the only federally-chartered mining museum in the United States and has been touted as the premier showcase of American mining.

It relates mining’s rich history and the role mining plays in our lives today. This is accomplished through extensive ore and mineral specimens, numerous artifacts and displays, photographs, maps, dioramas, tools, and machinery A small gift shop, with a good bookstore, and an art gallery are on the premises.

Let’s take a tour.

Visitors are greeted by a sculpture of a single-jack miner. These men drilled ten holes at a time into hard rock to prepare it for blasting. After blasting, the rock was moved back one foot at a time. On the second level, you will see several more sculptures to admire.

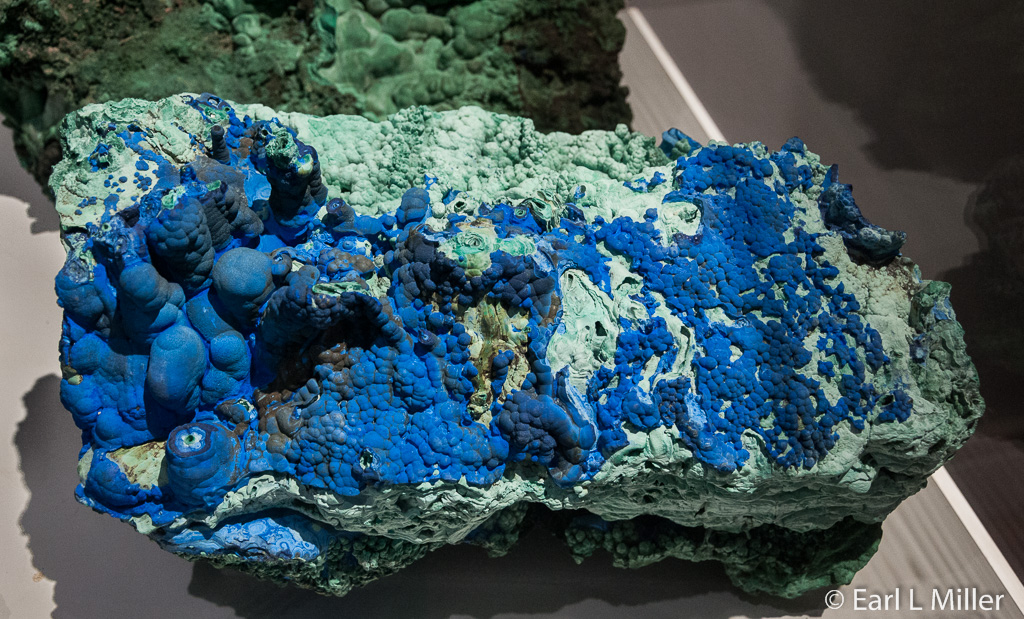

In the Crystal Room, you’ll find a variety of huge mineral specimens from around the world. These include jade, fluoride lead, malachite/azurite, and copper combined with other minerals. They include, in their display, jewelry such as a beautiful turquoise necklace. These were obtained from such places as Italy; the Gouverneur Mining District of New York; and the Tri State area of Missouri, Kansas, and Oklahoma.

Going through the hallway to the second level takes you through two areas. The Florescent Room has a variety of minerals under that type of light. They show up as red, green, and various shades of blues ranging from light to dark.

The other room you’ll pass is a walk through prospector cave. Lining one entire wall is iron pyrite or “fools’ gold” from the Eagle Mine in Gilman, Colorado. The entire opposite wall is quartz from the Idarado Mine near Telluride, Colorado. Some of these large quartz slabs weigh up to 400 pounds.

SECOND LEVEL

On the second level, you’ll find the Expanding Boundaries Exhibit and the Copper Room. Expanding Boundaries contains 11 meteorites from all over the world such as Siberia, the Philippines, Australia, and various United States areas. Take time to watch the video divided into three screens having conversations with each other. The one on the left is an old prospector, the middle has astronaut Harrison Schmitt, and the right one is a young man. These represent the past, present, and future of mining.

The Copper Room has a display on modern mining and reclamation. It contains three large models. These are the Minas de Ravas from Guanajuato, Mexico; Robert E. Lee Mine from Leadville (which you have seen on the driving tour); and Wolverine Mine from Kearsarge, Michigan. They have an exhibit on the 2010 Chilean rescue and a number of copper specimens from the Calumet and Hecla Mine in Calumet, Montana.

One exhibit had been collected by Bill and Lane Peters of Tucson, Arizona. You’ll see several icons and artifacts representing Santa Barbara, patron saint of the miners. These were collected from Germany; Taos and Santa Fe, New Mexico; and Italy.

Also on the second level is the new Hennebach Wing which houses extensive mineral specimens, a collection of miner tools, and a large room called the World of Molybdenum. The Sculpture Gallery contains 11 sculptures dedicated to blacksmiths and western coal.

The Frost Mineral Collection has more than 700 international specimens, all carefully labeled and placed by locales into different enclosed bookshelves. These are broken down into Asia, Africa, South and Central America, Island Nations, Europe, Mexico, Eastern United States and Canada, and the Western United States.

Opposite it is the smaller collection of Victor Hampton. He was a metallurgist/mining engineer who worked in the industry in both the United States and Bolivia.

At the room’s rear, you’ll find the Molybdenum Car - a 1923 Wills Sainte Claire. It was the first to use moly steel in the construction of its two camshafts, crank shaft, connecting rods, timing gears, front axle, wheel spindles, and more. It used chrome (moly combined with nickel.)

The World of Molybdenum Exhibit is extensive. Highlights are the three time lines on the room’s walls of Climax Mine history, moly industry, and national events from 1879 to 1982. You’ll learn such facts as moly was first found in 1879 but not identified until 1895. By 1926, the Climax produced 75% of the world’s moly output. It was first an underground mine which switched to limited open pit mining in 1948. By 1972, it was a full scale, open pit mine. In 1982, production ended at the Climax for the first time. This was due to a flood of competition and new technology enabled copper mines to get moly from waste. The Climax reopened in 2012. Climax was once a company town, and information is provided on that as well.

On this level, you’ll also find the Lighting Exhibit. This has a display of candles, oil lamps, carbide lamps, safety lamps, and electric lamps. The exhibit also contains a variety of drills with several examples of each type. There is an explanation of how the lamps and drills worked.

The castle made entirely out of minerals caught my attention. Don Miller, of Leadville, started building it in 1964 and finished this project in 1984. Near it, you’ll find obsidian, gold, iron, pyrites, and quartz on display, as well as photos of the Climax Mine.

HEAD FOR LEVELS 3 AND 4.

In this level’s foyer, you’ll see a model railroad. Unfortunately I did not view it working. It also has a case on mining exploration ranging from compasses and micrometers, which measure the magnetic field, to samples of different types of drilling cores.

Turn right to visit the fourth level starting with the Diorama Room. Hank Gentch of Englewood, Colorado carved 27 dioramas as “An Adventure to History”. These cover the history of Colorado mining from the discovery of gold by George Andrew Jackson in Idaho Springs through hydraulic and hard rock mining. Each, with the exception of two which are untitled, provides a detailed explanation of what you are seeing.

Follow the exit to the replica of the Hard Rock Mine which you can walk through. It’s quite extensive and shows how an underground mine operated. It has pipes and hoses from actual mines, an assay and blacksmith shop, a hoist house, depictions of miners drilling, and a bell system. Don’t be surprised to hear “Fire in the Hole.”

The Gold Rush Room features gold specimens from each of the 17 states which experienced major gold discoveries and prospecting booms. A highlight is the 24-ounce gold nugget retrieved from the Little Johny Mine. Exhibits are on placer mining and how to pan for gold.

You’ll learn the differences between pyrite and gold. Pyrite is found in cubes; gold is irregularly shaped. Pyrite is brighter and whiter than gold and also less dense and harder than gold. Pyrite is used in solar panel, paper production, batteries, radios, and jewelry.

Next to it is the Leadville Room which houses a case with different types of silver and objects produced from this mineral such as a pair of silver knitted gloves and a one ounce silver bar. The room also contains photographs of Leadville and a map of the Leadville Mining District.

Across from the Leadville Room is the Scale Room. Besides scales, you’ll see different types of decorated axes and canes used at ceremonial events and parades. This room also contains different drafting and mine surveying instruments.

Walk down the ramp and you’ll be on the third level. It contains the walk through Coal Mine dramatizing the history of coal mining.

Nearby, you’ll spot the exhibit about the famous Colorado Yule Marble Quarry in the Marble Room. Rock from this Marble, Colorado quarry was used to construct the Lincoln Memorial in 1916 and for the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at Arlington National Cemetery in 1931.

The most extensive displays on this level are in the area Minerals in Our Lives and the Magic of Minerals. Explanations show how minerals are used in space, building materials, and cosmetics. Some exhibit headings are Borax; Mining and Computers; Energy Sources - oil, shale, coal; and Health and Household Goods. For example, computer manufacturing requires 66 minerals.

Interactive displays of a home kitchen and office point out all the different items, including foods, requiring minerals. For example, broccoli receives potassium and phosphorous from fertilizers. Bread uses gypsum, soda ash, and titanium dioxide. The powder you see when you unwrap a stick of gum comes from limestone.

Another section is on how the Bureau of Land Management works with mining companies to help preplan mine layouts to reduce the environmental impact and then how the BLM monitors reclamation. You’ll learn about the mineral and energy resources found on U.S. forest lands.

LEVEL 5 - HALL OF FAME

The National Hall of Fame is chartered by Congress. It provides biographies on those who shaped the nation through mining Consideration is given to prospectors, miners, mining leaders, engineers, teachers, financiers, inventors, journalists, geologists, even a president, Herbert Hoover. New inductees are selected annually. As of September, 2014, the Hall of Fame had 227 inductees. Each has their own engraved photo and biography. To learn about those listed go to the following link: http://www.mininghalloffame.org/inductees

National Mining Hall of Fame and Museum is one of the few attractions open year round in Leadville. It’s located at 120 West 9th Street and the phone number is (719) 486-1229. Summer hours (May 11 to November 16) are 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. daily. The hours are the same during the rest of the year, but the museum is closed on Mondays. Admission is adults $9, seniors (65+) $7, teens $7, and children ages 6-12 $4. There is no admission fee for children under the age of three. Combination tickets are available with the Matchless Mine. The museum offers discounts for members of the AAA, AARP, and the military.

DID YOU KNOW

At 14,440 and 14,421 feet respectively, Mt. Elbert and Mt. Massive are the two highest peaks in Colorado and the highest peaks in the Rocky Mountains.

Leadville is highly regarded for its historical tourism. Driving the 20- square-mile Route of the Silver Kings and exploring the National Mining Hall of Fame and Museum are worthwhile ways to further discover Leadville’s mining heritage.

ROUTE OF THE SILVER KINGS

The Route of the Silver Kings consists of interconnected roads. It takes a couple of hours to see and covers ghost towns, mines, a smelter, and a power plant. You’ll be driving on public dirt roads, but the mines are on private property, so it’s necessary to respect the “No Trespassing” signs. You aren’t allowed to enter any of the mine shafts or tunnels. Rock collecting and treasure hunting are prohibited. Taking a camera pays off since you will encounter many good photographic opportunities.

To fully enjoy your drive, you can obtain the brochure The Route of the Silver Kings from the Leadville/Lake County Visitor Center located at 809 Harrison Avenue. The brochure has a map that makes the combined two routes easier to follow. The Center is also a great stop to pick up information about other area places to visit.

To reach Stop #1, start your self guided driving tour at Monroe Street and Harrison Avenue. Continuing East, the first route takes you from the first to the fourth point. The second part of your drive starts on 7th Street on Harrison Avenue. It contains the other 10 stops.

Look for the 14 numbered signs, each indicating a point of interest. Be aware that where the brochure indicates mileage, such as 1.1 miles to the power plant, then A.Y. and Minnie mine 2.0 miles on the right, you measure from the beginning of each of the two routes. In this case, you travel to the second point 2.0 miles total. It is not the distance between points. This can be confusing so it’s very important to look for the numbered signs indicating a stop.

Stop #1 is the Harrison Reduction Works. These were one of 17 area smelters operating between 1879 and 1960. At the Harrison, they removed the silver from lead carbonate ore.

Stop #2 are the Yak Tunnel and the Power Plant. A steam powered generating plant existed in the red brick building. It provided electricity for the nearby mines. The four-mile Yak tunnel, built between 1895 and 1923, drained water and transported ore from the mines in the southern part of the district.

Stop #3 are Meyer Guggenheim’s A.Y. and Minnie Mines. They received their name because they were originally discovered by A.Y. Corman and his wife, Minnie. These were the foundation of the Guggenheim fortune. These two mines turned a profit of $2,000 a day and kept that up for a decade. Unfortunately his son, Benjamin, who was watching these mines for his father drowned, at age 46, in the sinking of the Titanic.

Stop #4 is Oro City (a mile northeast of Leadville). It’s where Abe Lee discovered placer gold in 1860, and the site of the single richest, placer gold strike in the entire Pikes Peak rush. In seven years, miners washed ten tons of gold, worth more than $5 million, from California Gulch. Oro City reached a peak population of 10,000. It nearly disappeared when the gold depleted until the silver boom in 1874. By 1890, only 222 people occupied this site. Today no structures remain standing, but you can see foundations and piles of gravel.

Stop #5 is where the town of Adelaide Park existed. The town started to form in 1876, around the Adelaide Mine, and by 1879 had a population of more than 1,000. Later, approximately 2,500 people lived here, and it housed 28 businesses. The town discontinued the post office in 1880. Today, nothing remains except for a few foundations.

Stop #6 is the Mikado or Gallagher Shaft. This mine, in 1887, employed 120 men. The ghosts of three of the five miners killed in the Mikado were supposed to wander in spirit form until the mid 1890's. Many miners quit their job as a result of these haunts. Today, only decaying timbers and the mine dumps remain. It produced lead-zinc sulphide and zinc carbonate at the rate of 150 tons a day.

Stop #7 is Finn Town. It was first settled by miners from England. In the 1890's large numbers of Scandinavians moved to Finn Town. They had stores, saloons, and a sauna.

This is also the location of the head frame of the Robert Emmet Mine. It was a lead-zinc and silver producer. During the miners’ strike of 1896-1897, a battle occurred between the strikers and mine guards here.

The strike closed 90% of the mines when miners sought a pay of $3 a day from the $2.50 they were reduced to during the 1893 Silver Panic. Mine owners, like Tabor, brought in the state militia which didn’t help the situation. Six months later the miners returned to work without a pay increase. The strike ended March 9, 1897. Many of the area mines closed and never reopened because, during the strike, the unpumped water accumulated and had carried large amounts of sand into the shafts sealing the mines.

Also at this stop, you’ll find the site of the Wolftone Mine, one of the Guggenheim properties in the late 1890s. In 1910, Samuel D. Nicholson, the mine manager, found a rich source of zinc. On January 11, 1911, to celebrate, he had an elaborate party for more than 250 people underground.

Sleighs provided the transportation from Tabor’s Grand Hotel to the banquet. As visitors drove by, the other mines, large American flags and mine whistles saluted them.

After touring the mine and its facilities, only six persons, at a time, rode the cage down to the 1,000 foot level. They were taken along a 75-foot dirt hallway, that was well lit with electric fixtures, to a banquet room - 110 feet long, 25 feet wide, and 10 feet high. Management had removed a total of 220 cubic feet of rock, $150,000 in minerals, to create this room. Colored bulbs projected hues on the rock and dirt walls. Bouquets and flower arrangements decorated two 100-foot tables.

Present at the catered dinner were two men playing bagpipes in tradition with the 152nd Anniversary of Scottish poet, Bobbie Burns. A six-piece orchestra also performed. After the party, the banquet room remained open to citizens, including tours by school children, for several days. On January 29, management removed the decorations and the mine resumed normal operations.

The discovery eventually led to the construction of the Western Zinc Oxide Smelting Company

Stop #8 is the location of wooden cribbing marking the site of the Coronado Mine. On September 21, 1896, the striking miners set the surface buildings on fire. The fire killed three men including a Leadville fireman, who was shot while turning on water to extinguish the flames.

Stop #9 is Fryer Hill, named after George Fryer, who staked the New Discovery claim in 1878. This was the location of three silver producing mines. It was the home of the Little Pittsburg where Horace Tabor grubstaked August Rische and George Hook in 1878 in exchange for one-third interest. It yielded $8,000 a week. Within a year, he sold it for one million dollars.

Another is the Chrysolite Shaft which paid off big for Tabor. It was salted by “Chicken Bill” Lovell with stolen, high grade ore to attract a high price. Tabor purchased it, dug down another 25 feet, and then sold it after it produced $1.5 million dollars. He later sold the mine to others including Marshall Field of Chicago merchandising fame.

The Robert E. Lee Mine produced $3 million by 1882. It was called “The Silver Vault” of Fryer Hill.

Take time at this stop to notice the head frame of the Wright Shaft for the Denver City Mine. Its A-shape was a prominent feature of the tin mine head frames found in Cornwall, England. The shaft runs 320 feet deep.

Stop #10 is Evansville, a small mining camp in 1880, where families of miners employed in nearby mines lived. It reached a peak population of 1,000 in the 1890's but disappeared by the 1930's Depression. You can still spot some of the cabins’ stone foundations.

Stop #11 is the Resurrection Mine No. 2 Shaft which operated until a fire destroyed its surface plant in 1956. Miners extracted lead, zinc, gold, and silver from this 1,000 foot shaft then sent the minerals through the connecting Yak Tunnel to the California Gulch mill. Nearby, you’ll find the tall, modern head frame and other buildings of the Diamond Shaft. Until it closed in 1988, its primary product was gold.

Stop #12 was first called “South Evans” but was later named Stumptown. The settlement began in 1879 with the discovery of lead carbonate ores in the Little Ellen Mine. It was largely abandoned in the late 1930's. You’ll see the remains of several buildings at this stop.

It was primarily a residential town with a few saloons. Houses were small and none had indoor plumbing. Water for cooking and bathing came from the town pump. Margaret “Molly” Brown arrived in the early 1880s and lived in Stumptown for a year, as a young bride, before residing in Leadville.

Stop #13 is the Ibex Mine Complex, consisting of the town of Ibex and five shafts operated by Ibex Mining Company. The number one shaft was known as the Little Johny Mine. It was here that J.J. Brown, Margaret’s husband, the superintendent of all the Ibex properties, devised a way to overcome drainage problems at this site in the early 1890s. He was rewarded with 1/8th of the interest in the mine which had vast quantities of high-grade copper and gold. This accounted for the Browns’ fortune.

If you have a four-wheel drive on your vehicle, then you may want to take in stop #14. You have to travel up a steep hill, not recommended for your normal family car, to the Venir Shaft where gold was produced until the 1940's. We felt that because of its isolation, it was the best preserved area on the route. You will also have excellent views of Turquoise Lake, and Colorado’s tallest mountains, Mt. Elbert and Mt. Massive.

NATIONAL MINING HALL OF FAME AND MUSEUM

Plan on spending a minimum of three to four hours at this 20-room museum, in addition to open areas and hallways, which once housed Leadville’s junior high and then senior high. Opened to the public in 1987, it represents mining from all over the world. It is the only federally-chartered mining museum in the United States and has been touted as the premier showcase of American mining.

It relates mining’s rich history and the role mining plays in our lives today. This is accomplished through extensive ore and mineral specimens, numerous artifacts and displays, photographs, maps, dioramas, tools, and machinery A small gift shop, with a good bookstore, and an art gallery are on the premises.

Let’s take a tour.

Visitors are greeted by a sculpture of a single-jack miner. These men drilled ten holes at a time into hard rock to prepare it for blasting. After blasting, the rock was moved back one foot at a time. On the second level, you will see several more sculptures to admire.

In the Crystal Room, you’ll find a variety of huge mineral specimens from around the world. These include jade, fluoride lead, malachite/azurite, and copper combined with other minerals. They include, in their display, jewelry such as a beautiful turquoise necklace. These were obtained from such places as Italy; the Gouverneur Mining District of New York; and the Tri State area of Missouri, Kansas, and Oklahoma.

Going through the hallway to the second level takes you through two areas. The Florescent Room has a variety of minerals under that type of light. They show up as red, green, and various shades of blues ranging from light to dark.

The other room you’ll pass is a walk through prospector cave. Lining one entire wall is iron pyrite or “fools’ gold” from the Eagle Mine in Gilman, Colorado. The entire opposite wall is quartz from the Idarado Mine near Telluride, Colorado. Some of these large quartz slabs weigh up to 400 pounds.

SECOND LEVEL

On the second level, you’ll find the Expanding Boundaries Exhibit and the Copper Room. Expanding Boundaries contains 11 meteorites from all over the world such as Siberia, the Philippines, Australia, and various United States areas. Take time to watch the video divided into three screens having conversations with each other. The one on the left is an old prospector, the middle has astronaut Harrison Schmitt, and the right one is a young man. These represent the past, present, and future of mining.

The Copper Room has a display on modern mining and reclamation. It contains three large models. These are the Minas de Ravas from Guanajuato, Mexico; Robert E. Lee Mine from Leadville (which you have seen on the driving tour); and Wolverine Mine from Kearsarge, Michigan. They have an exhibit on the 2010 Chilean rescue and a number of copper specimens from the Calumet and Hecla Mine in Calumet, Montana.

One exhibit had been collected by Bill and Lane Peters of Tucson, Arizona. You’ll see several icons and artifacts representing Santa Barbara, patron saint of the miners. These were collected from Germany; Taos and Santa Fe, New Mexico; and Italy.

Also on the second level is the new Hennebach Wing which houses extensive mineral specimens, a collection of miner tools, and a large room called the World of Molybdenum. The Sculpture Gallery contains 11 sculptures dedicated to blacksmiths and western coal.

The Frost Mineral Collection has more than 700 international specimens, all carefully labeled and placed by locales into different enclosed bookshelves. These are broken down into Asia, Africa, South and Central America, Island Nations, Europe, Mexico, Eastern United States and Canada, and the Western United States.

Opposite it is the smaller collection of Victor Hampton. He was a metallurgist/mining engineer who worked in the industry in both the United States and Bolivia.

At the room’s rear, you’ll find the Molybdenum Car - a 1923 Wills Sainte Claire. It was the first to use moly steel in the construction of its two camshafts, crank shaft, connecting rods, timing gears, front axle, wheel spindles, and more. It used chrome (moly combined with nickel.)

The World of Molybdenum Exhibit is extensive. Highlights are the three time lines on the room’s walls of Climax Mine history, moly industry, and national events from 1879 to 1982. You’ll learn such facts as moly was first found in 1879 but not identified until 1895. By 1926, the Climax produced 75% of the world’s moly output. It was first an underground mine which switched to limited open pit mining in 1948. By 1972, it was a full scale, open pit mine. In 1982, production ended at the Climax for the first time. This was due to a flood of competition and new technology enabled copper mines to get moly from waste. The Climax reopened in 2012. Climax was once a company town, and information is provided on that as well.

On this level, you’ll also find the Lighting Exhibit. This has a display of candles, oil lamps, carbide lamps, safety lamps, and electric lamps. The exhibit also contains a variety of drills with several examples of each type. There is an explanation of how the lamps and drills worked.

The castle made entirely out of minerals caught my attention. Don Miller, of Leadville, started building it in 1964 and finished this project in 1984. Near it, you’ll find obsidian, gold, iron, pyrites, and quartz on display, as well as photos of the Climax Mine.

HEAD FOR LEVELS 3 AND 4.

In this level’s foyer, you’ll see a model railroad. Unfortunately I did not view it working. It also has a case on mining exploration ranging from compasses and micrometers, which measure the magnetic field, to samples of different types of drilling cores.

Turn right to visit the fourth level starting with the Diorama Room. Hank Gentch of Englewood, Colorado carved 27 dioramas as “An Adventure to History”. These cover the history of Colorado mining from the discovery of gold by George Andrew Jackson in Idaho Springs through hydraulic and hard rock mining. Each, with the exception of two which are untitled, provides a detailed explanation of what you are seeing.

Follow the exit to the replica of the Hard Rock Mine which you can walk through. It’s quite extensive and shows how an underground mine operated. It has pipes and hoses from actual mines, an assay and blacksmith shop, a hoist house, depictions of miners drilling, and a bell system. Don’t be surprised to hear “Fire in the Hole.”

The Gold Rush Room features gold specimens from each of the 17 states which experienced major gold discoveries and prospecting booms. A highlight is the 24-ounce gold nugget retrieved from the Little Johny Mine. Exhibits are on placer mining and how to pan for gold.

You’ll learn the differences between pyrite and gold. Pyrite is found in cubes; gold is irregularly shaped. Pyrite is brighter and whiter than gold and also less dense and harder than gold. Pyrite is used in solar panel, paper production, batteries, radios, and jewelry.

Next to it is the Leadville Room which houses a case with different types of silver and objects produced from this mineral such as a pair of silver knitted gloves and a one ounce silver bar. The room also contains photographs of Leadville and a map of the Leadville Mining District.

Across from the Leadville Room is the Scale Room. Besides scales, you’ll see different types of decorated axes and canes used at ceremonial events and parades. This room also contains different drafting and mine surveying instruments.

Walk down the ramp and you’ll be on the third level. It contains the walk through Coal Mine dramatizing the history of coal mining.

Nearby, you’ll spot the exhibit about the famous Colorado Yule Marble Quarry in the Marble Room. Rock from this Marble, Colorado quarry was used to construct the Lincoln Memorial in 1916 and for the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at Arlington National Cemetery in 1931.

The most extensive displays on this level are in the area Minerals in Our Lives and the Magic of Minerals. Explanations show how minerals are used in space, building materials, and cosmetics. Some exhibit headings are Borax; Mining and Computers; Energy Sources - oil, shale, coal; and Health and Household Goods. For example, computer manufacturing requires 66 minerals.

Interactive displays of a home kitchen and office point out all the different items, including foods, requiring minerals. For example, broccoli receives potassium and phosphorous from fertilizers. Bread uses gypsum, soda ash, and titanium dioxide. The powder you see when you unwrap a stick of gum comes from limestone.

Another section is on how the Bureau of Land Management works with mining companies to help preplan mine layouts to reduce the environmental impact and then how the BLM monitors reclamation. You’ll learn about the mineral and energy resources found on U.S. forest lands.

LEVEL 5 - HALL OF FAME

The National Hall of Fame is chartered by Congress. It provides biographies on those who shaped the nation through mining Consideration is given to prospectors, miners, mining leaders, engineers, teachers, financiers, inventors, journalists, geologists, even a president, Herbert Hoover. New inductees are selected annually. As of September, 2014, the Hall of Fame had 227 inductees. Each has their own engraved photo and biography. To learn about those listed go to the following link: http://www.mininghalloffame.org/inductees

National Mining Hall of Fame and Museum is one of the few attractions open year round in Leadville. It’s located at 120 West 9th Street and the phone number is (719) 486-1229. Summer hours (May 11 to November 16) are 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. daily. The hours are the same during the rest of the year, but the museum is closed on Mondays. Admission is adults $9, seniors (65+) $7, teens $7, and children ages 6-12 $4. There is no admission fee for children under the age of three. Combination tickets are available with the Matchless Mine. The museum offers discounts for members of the AAA, AARP, and the military.

DID YOU KNOW

At 14,440 and 14,421 feet respectively, Mt. Elbert and Mt. Massive are the two highest peaks in Colorado and the highest peaks in the Rocky Mountains.

The Yak Tunnel & Power Plant

A.Y. and Minnie Mines

The Robert Emmet Mine

Finn Town

The Diamond Shaft

Stumptown

Stumptown

Ibex Mine Complex

Ibex Mine Complex

Venir Shaft

Venir Shaft

National Mining Hall of Fame and Museum

Single Jack Miner sculpted by Lori Atz at National Mining Hall of Fame and Museum

Malachite/Azurite

Amethyst Geode

Model of Robert E. Lee Mine

Don Miller's Mineral Castle

The World of Molybdenum Exhibit

Walk Through Hard Rock Mine