Hello Everyone,

As you approach Interstate 80's exit 275, you’ll find a massive structure, in the form of an arch, spanning above all of its lanes. It was designed by a Walt Disney team from Orlando. Known as the Great Platte River Road Archway, it’s one of Nebraska’s best known attractions.

Go inside and you’ll be greeted by 21 life-sized figures, all cast from live models. They are part of more than 20 detailed audiovisual displays relating the history of the Great Platte River Road and 170 years of America’s westward movement.

ARCHWAY ARCHITECTURE

Frank Morrison, who served as Nebraska’s governor from 1961-1967, conceived the idea of the Archway. He wanted to build a memorial dedicated to the pioneers who traveled the Great Platte River Route. Since the idea was to resemble a covered bridge, two towers were erected - one on each side of the road, They serve as the structure’s anchors.

The Archway’s exterior design resembles a Nebraska sunset. Its stainless steel exterior was especially treated using electrically charged acid to create the yellows, oranges, and reds to tie its exterior color to that of the Midwest.

Groundbreaking occurred in 1998. After the entire arch structure was constructed at ground level on the south side of the highway, the arch section was lifted 22.5 feet into the air using hydraulic jacks. Then, it was jacked horizontally onto heavy duty, self-propelled, modular transporters that carried the structure across the highway. The process of lifting the structure onto the transporters took eight days.

It was rolled across I-80 at 10:00 p.m. on the evening of August 16, 1999. By 6:00 a.m. on August 17, the arch segment was in place over concrete abutment walls. It was then welded into place and finishing work began. The museum opened June 9, 2000.

Encompassing 79,000 square feet, the arch spans 308 feet across I-80. The building is topped by a 7-ton aluminum and steel sculpture. Its braided trellis refers to the “braided river”, the Platte. The wings convey a feeling of energy, wind, and sky as well as waves of water and grain.

The arch weighs 1,500 tons and is 116 feet tall from the ground to the tip of the wings of the sculpture on top. Its massive spruce logs in the lobby came from Montana and Canada while the sandstone slate flooring is from Colorado.

FIRST LEVEL OF EXHIBITS

Upon paying admission, at the front desk in the north tower, you will receive a pair of headphones for each member of your party. These are attached to an audio guide. You punch into the unit the corresponding number you’ll spot at various locations as you proceed along the trail. This allows you to hear the stories of people and gain more details about places and historical events that you view. You’ll become totally immersed as you hear sounds, read signs, and watch videos, made to look 3D by their surroundings, as you travel from the mid 1800's through watching today’s cars on the interstate.

Platte River Traders Gift Shop is extensive. It carries Nebraskan and American-made products ranging from clothing and locally made specialty foods to souvenirs. Stuffed animal fans will have an opportunity to purchase the museum’s mascot, Archie the buffalo. Want to search for fossils, minerals, or gemstones? Purchase a bag of mining rough at the gift shop and use the Archway’s new mining sluices to find your treasures. This is also the location to pick up sandwiches, snacks, popcorn, and drinks for the road.

Head to the exhibits upstairs by taking a two-story escalator, the second longest in Nebraska. You will be guided by statues of pioneers pointing the way up as you ascend. Ahead of you is a moving video of settlers following the Great Platte River Road.

You start your experience with a Native American showing a fur trader the path along the North Platte River, circa 1820.

Next you’ll travel to Fort Kearny (spelled differently from the city) established in 1848 near Kearney, Nebraska. It was a supply point for the pioneers as well as freight and Pony Express station. Later in its history, it served to protect workers on the Transcontinental Railroad. Look for the case of artifacts and tools found at the fort. These include ox shoes, bullets, keys, and a daguerreotype photo frame. You will also see a door latch, arrowheads and spearheads, grapeshot, and a cavalry hoof pick.

Read about the early wagon trains and join one as you proceed further west. The sign “Hitting the Trail” explains that the first emigrant wagon headed west in 1841. At that time, only a handful made the trip. However, in 1843, under the leadership of Marcus Whitman, one thousand men, women, and children made their way to the Pacific Northwest. Thousands of pioneers, mostly farmers seeking fertile soil and long growing seasons in Oregon and California, followed over the next five years.

Another sign is on Indian territory. The Native Americans had lived in the area for centuries. It was the land of the Pawnee, Sioux, and Cheyenne. In the early stages, as the pioneers passed through the West, the Indians would help with food, directions, and occasionally assist the settlers across rivers. Relationships were peaceful with emigrants dying more from drowning at river crossings and accidents with their own guns than because of the Indians.

As you walk along, you’ll spot a woman pushing a wagon while a man walks up front alongside the oxen pulling a Conestoga wagon. You hear the clatter of wagons and hear the occasional cry of a baby. Watch out for the storm ahead as you see lightning and hear thunder. Off to one side, a large video of a field erupts with a herd of stampeding buffaloes.

The site of stampeding buffaloes was one of the most memorable experiences for pioneers. One pioneer estimated that the number of beasts he encountered exceeded two million. The Native Americans considered the animal as a way of life and were dependent on it for rituals, food, clothing, and shelter.

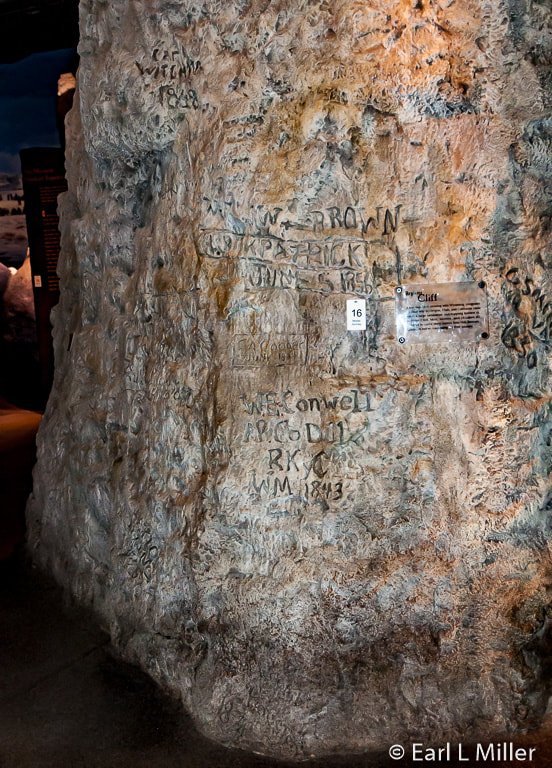

A few days after passing into Wyoming, you’ll pass Register Cliff. Examine it carefully to see the many names and dates inscribed by men, women, and children as they came upon this large sandstone outcropping on their way to Oregon, Utah, and California.

Next to Register Cliff, read the story of how Brigham Young led a band of Mormons to their “New Zion” in Salt Lake City in 1847. You’ll hear horses neighing and wolves howling in the distance. A wolf stands on a hill nearby.

On April 14, 1847, Brigham Young led a well equipped and organized company of 143 men, women, and children across the Great Platte River Road to the Valley of the Great Salt Lake. They had been driven from Illinois and sought a new home free of religious prejudice for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Young declared, “This is the place.” The trip took four months. Over the next 23 years, 80,000 Mormons moved to Utah by foot, horseback, wagon, and handcart.

In 1856, two companies of European Mormons headed across the Great Platte River Route. They ignored advice not to leave Iowa City in late summer. Unable to afford covered wagons, they piled their goods onto handcarts for the 1,400 mile trek to Salt Lake City. Deadly fall blizzards trapped them in Wyoming’s Sweetwater Valley. Young dispatched volunteers from Salt Lake City and rescued more than 800 of the 1,076 immigrants.

The background mural reflects this event showing people trying to survive in deep snow. The scene has several mannequins - a young father, carrying a baby, talking to an elderly woman while a man steers a heavy cart.

A sign about Joseph Goldsborough Bruff, one of the California 49ers, is nearby. A West Point graduate and government draftsman, he decided at the age of 44 to lead a company of 66 men to California. He documented his journey with sketches and diaries. His entries recorded the landscape, encounters with other emigrants, and struggles to keep the company together. Like many, he never found gold and attempts to sell his journal went unpublished during his lifetime.

You’ll see a scene of men, using the shelf of a cliff as shelter. One sits. The other two stand around a campfire. Maybe they’re dreaming of becoming rich some day. A donkey stands nearby as you hear the blast of strong winds coming through their site.

Read a sign as to how gold in 1848 was discovered at Sutter’s Mill in California’s American River. This sparked a frenzied migration west. Men from the East Coast boarded any ships they could find to take them to Panama or around South America to San Francisco. Others traveled along the Great Platte River Road. Not too many succeeded in finding their dreams as by 1849, the gold had panned out.

The “Memorials of Passage” sign reminds visitors that as pioneers approached the Rocky Mountains the trail’s rigors took its toll. As the ox teams buckled due to the over packed wagons through snow and mud, pioneers began to lighten their loads. They tossed out food, tools, and family heirlooms along the trail.

Death became a great concern. Accidents and diseases like cholera killed one in 17 who started out. Since it was vital to arrive at their destinations before winter, family members were quickly buried so the wagons could continue on the trail. Native Americans suffered from deadly diseases they caught from the settlers and had their ancient hunting grounds disrupted.

The background mural near the sign depicts several Conestoga wagons rolling across the prairie. A family is saying goodbye to a loved one who has died on the trail. Again, you hear the howl of wolves. It also displays a real wagon that has broken down. Two wheels have fallen off and its canvas is in tatters. Family treasures have been tossed to the ground. You’ll spot a small chest of fine china, a broken organ, an upholstered footstool, and a beautiful clock. Diaries lay scattered about.

You have now reached the crossroads of hundreds of miles of the highest mountains and need to decide which of three routes you will take here. You’ll find an interactive exhibit. Choose wisely which passage you will take after receiving advice at the trail side “post office.” You will learn the results of each. It could be a matter of survival. Sometimes the path was chosen on the flip of a coin.

In the next room, you’ll hear train bells and see a large map of the California, 49ers, Oregon, and Mormon Trails. The sign in the room “The West at Last” mentions that between 1841 and 1866, almost 350,000 men, women, and children made the difficult journey west along the Great Platte River Road finally reaching their destinations. This area has lots of information on those who followed the trails and displays some of their artifacts. It covers such aspects as the Mountain Men, Donner Pass, and Brigham Young’s “This is the Place.”

In 1846, George Donner, an Illinois farmer, led a wagon train of 86 to California. After a series of delays and bad advice, they took an untested shortcut through the Utah territory. Traveling across the High Sierras, in California, early snows trapped the group near Truckee Lake. They pieced together makeshift tents in an attempt to wait out the winter. Supplies became so drastically low that they ate oxen hides, shoe leather, even the family dog. They sent out a party of 15 for help. Only seven made it through to find aid. When they returned, only 47 had survived as many had to resort to cannibalism to stay alive.

Another section in this room is dedicated to “Women of the West.” By 1841, women accompanied almost every wagon train. They unloaded wagons, pitched tents, and yoked the oxen. However, they were also responsible for taking care of the children, washing clothes, baking bread, and recording their experiences in journals.

Narcissa Whitman and Eliza Spalding followed the Road with their husbands in 1836. Their aim was to bring Christianity to Pacific Northwest Indians. They were the first white women to cross the Continental Divide as well as the country.

Bridget “Biddy” Mason was a slave who followed her master to the free state of California in 1851. She drove the last of the 300 wagons while tending to her three daughters and herding livestock along the entire route. She won her family’s freedom in the California courts five years after their arrival. Biddy became a nurse and saved enough money to buy 10 acres of land in what is now downtown Los Angeles. Known because of her kind heart, she spread her fortune feeding the poor, establishing nursing homes, clothing flood victims, and founding a school and a church.

“This is the Place” sign relates more of the Mormon story. When Brigham Young led his group into the Valley of the Great Salt Lake, he knew he had found the right place. However, many didn’t agree with him since the land was barren and dry.

The sign says: “I want hard times,” he said, “so that every person that does not wish to stay for the sake of his religion will leave.” Young quickly ordered houses constructed, crops planted, and irrigation systems built. Although the Mormons barely survived the first two winters, soon the group prospered with farms, textile mills, and tanneries.

Take time to observe the case with Mormon items: a Mormon odometer, a Nauvoo temple plate, a pioneer jubilee cup, and a Mormon song book. Learn more about the prospectors’ lives as you read about “Early Frisco” and “Boomtown by the Bay.” Note the gold pan and large pick.

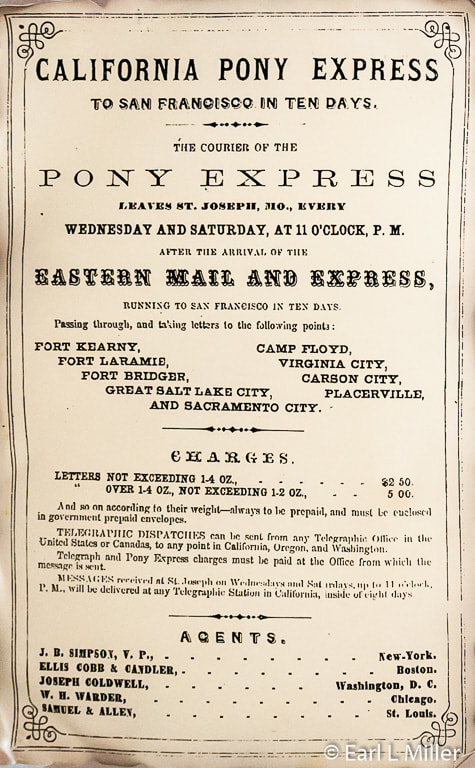

Watch the arrival on the video screen as the Pony Express rider comes quickly toward you to mount another horse and continue his run to deliver mail across the country. To learn more about the Pony Express, go to my article on Ogallala.

Look for the Pawnee scouts and soldier standing together. A sign relates that Major Frank North formed the Pawnee battalion with four companies of scouts led by white officers and Pawnee non-commissioned officers. The scouts guarded the 300-mile Union Pacific stretch from Lexington, Nebraska to Laramie, Wyoming during the summers if 1867 and 1868. The scouts successfully defended the railroad workers in skirmishes against warriors from the camps of Red Cloud (Oglala), Little Crow (Arapaho), Turkey Leg (Cheyenne), and Spotted Tail (Lakota) with the Pawnee losing few if any men.

You will see an Overland stagecoach. It was the way to travel across the country until the Transcontinental Railroad was completed in 1869. It hauled cargo, mail, and passengers for more than a decade across the Great Platte River Road to the West Coast. The fare per person from Fort Kearney to California could cost up to $500. It was an uncomfortable ride with as many as 20 people piled into and on top of the carriage, a vehicle that bounced and rattled over uneven dirt trails. Adding to the difficulties was bad weather and breakdowns. Listen on your audio device to Mark Twain’s account of a cross-country stagecoach trip.

The first transcontinental telegraph was completed on October 24, 1861 eliminating the need for the Pony Express. Operators for telegraph lines often used the former Pony Express stations. You can listen on your audio device as the first message is transmitted to the West coast: the news about the breakout of the Civil War.

SECOND LEVEL EXHIBITS

Go upstairs and you will reach the section on the Transcontinental Railroad. You see flashing lights as you hear the big locomotive roar as a train clanks overhead. One huge mural is a photo of the Golden Spike scene at Promontory Summit. A replica of that spike and a 1939 commemorative Golden Spike cane are in a display case. Another holds a survey compass and rail sections.

Read “Race for Riches” about the race between the Central Pacific and Union Pacific Railroads after President Lincoln signed the Pacific Railroad Act in 1862. The act promised loans and land grants for each mile of railroad built across the United States. The Union Pacific started in Omaha while the Central Pacific was built from Sacramento. It took six years of labor before they linked at Promontory Summit in Utah.

“The Iron Road” details that thousands of Chinese workers for the Central Pacific blasted through the granite ridges of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. Civil War veterans and Irish immigrants employed by the Union Pacific faced attacks from Native Americans. Other obstacles were blizzards during the winter and searing summer heat.

Notice the large sign advertising the route from Omaha to San Francisco touting the benefits of Pullman’s Palace sleeping cars. Another ad acknowledges the death of the Conestoga wagon and the pleasures of taking a train.

Five days after the Golden Spike was celebrated at Promontory Summit, the Union Pacific Railroad began regular service to the West. This brought an almost immediate end to covered wagons along the Great Platte River Route since trains were faster and more economical. Pioneers lined up for cross country tickets that cost $50 to go between Omaha and Sacramento in a week.

Many of the Union Pacific passengers headed to the West’s interior rather than California. There the Union Pacific was attracting tens of thousands of immigrants by selling land it had acquired during the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad. The price was $2.75 an acre. Soon small towns sprang up along the rail lines. For ranchers, miners, farmers, and merchants, the Union Pacific was an economic lifeline.

Your next stop is the Lincoln Highway, also known as United States Route 30, the nation’s first transcontinental road. It was established in 1912 by Carl Fisher, who also founded the Indianapolis Speedway. His goal was to complete the coast-to-coast highway in time for the 1915 Panama Pacific Exposition in San Francisco. After much fund raising and support from New York to California, the 3,389 mile road was dedicated in October 1913. It followed the Great Platte River Road.

Against a backdrop of a campground and cabins, you’ll observe a Model T in the middle of a scene which includes Kozy Kabins. A grandfather and his grandson sit around a campfire near a tent and folding chairs. A classic Oldsmobile is next to them.

While promoting the highway, the Lincoln Highway Association originally recommended that billboards be banned from roadsides. The United States Rubber Company billboards got around this by erecting “historical bulletins” in 30 different locations along the route.

The Archway displays one of these In the shape of a book. It says “United States Tires are Good Tires.” It reminds automobile passengers that the historical bulletins bring you interesting facts about the places you visit. They are pleasant reminders of Royal Cords. The company put out a brochure listing the location of these bulletins.

Below the billboard, you’ll find fascinating information on the states through which the Lincoln Highway ran. Did you know that many communities along the route raised money to help construction of “seedling miles?” These funds replaced the dirt road with mile-long sections of concrete roadway. To aid in navigation of the highway’s twists and turns, crews placed red, blue, and white porcelain markers along the route. The Lincoln Highway was called the Main Street of America for two reasons. It tied countless cities and towns together and seemed to link the country together along a common “Main Street.”

You’ll also learn that the Lincoln Highway allowed exploration by car, increasing popular tourism dramatically. Motorists now flocked to resorts, state parks, and summer cottages to take their vacations. Undiscovered towns in the East, Midwest, and West became stopping points where tourist attractions sprang up and vacationers learned about local food and culture.

Many toured the country by day. At night, they camped by the side of the road or at campgrounds set up by towns to attract tourists. Some enterprises offered private campsites with fresh water and hot showers. Other conveniences like hot meals and small cabins were added later.

Look to your right. You’ll find a drive-in complete with speakers with a screen playing a newsreel about the rise of the American highway system. A driver watches from a 1962 Cadillac Coupe D’Ville.

Nearby is the Interstate 80 Roadside Café, a diner complete with bright red booths and a waitress, typical of that period, wearing unique sunglasses and pouring coffee. One background mural outside the diner is of Yellowstone National Park. Another is a giant map of the Great Platte River Road. Inside is a mural by Kenneth B. Gore featuring the portraits of many of the people who worked on the development of the Archway.

Discover how President Eisenhower passed the Federal Highway Act in 1956. That legislation provided funds for the construction of the interstate highway system. In 1974, Nebraska was the first state to complete construction of all of its mainline I-80 highway components. I-80 traces the Great Platte River Route and the old Lincoln Highway from New York to San Francisco tying together 11 states.

At the Roadside Café, look through the window with fixed radar guns at I-80 traffic below. According to Archway’s director Mark Foradori, that is many people’s favorite stop in the museum.

You should allow a minimum of one hour to see all the sights and hear all the sounds of the Archway. If you’re touring the state during June through August, you may also want to stop at the Nebraska Tourist Information Center near where you enter the Archway.

WHAT YOU SEE OUTSIDE

Several attractions are associated with the Archway that are outside the structure. One is the fort-like maze called the TrailBlaze Maze covering 4,000 square feet. The goal is to see who can wind around twisting turns to get to the four corners of the maze the fastest. This is a free seasonal attraction, open Memorial Day through Labor Day, which attracts children.

It’s easy to note the variety of sculptures you will find on the Archway campus. One that draws attention is the giant bison sculpted by Gary Ginther.

The Archway’s Pratt truss bridge leads to their picnic shelter, sod house, and bike/hike trail. The Canton Bridge Company of Canton, Ohio, a city on the Lincoln Highway, fabricated it in 1914. Its original home was across the Elkhorn River in Pierce, Nebraska. In 2005, it was installed at the Archway.

The replica sod house, built in 2006, reveals what life was like for Nebraska’s first pioneers. Since trees were scarce, they lived in sod homes, often built near the river. This enabled the settlers to trade with travelers who followed the trails along the riverbanks. It is open year round.

You may want to feed the fish or try your luck catching them in the Archway’s lake. Catch and release is strongly recommended. Species range from bluegill, largemouth bass, and small mouth bass to yellow perch, carp, and more. You can use people powered or electric motor boats on the lake, but gasoline powered boats and swimming are banned. Lake access is admission free.

The hike/bike trails allow you to explore the wooded area just north of the Archway. The 4.1 mile trail leads south to Fort Kearney while the 8.2 mile trail leads north to Kearney’s Cottonmill Park.

DETAILS

The Archway is located at Exit 275 on I-80. The telephone number is (308) 237-1000. Hours are Memorial Day through Labor Day Monday-Saturday 9:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. and on Sunday from noon to 6:00 p.m. Labor Day through Memorial Day, the hours are Monday-Saturday 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. and Sunday noon to 5:00 p.m. It’s closed on New Year’s Day, Thanksgiving, Christmas Eve, Christmas Day, and Easter.

Admission to the historical exhibit is Adults (13+) $12, Seniors (62+) $11, Ages 6-12 $6, Ages 5 and under free. Tax is added to all admissions. Parking is free with room for cars and RVs.

Great Platte River Road Archway Over I-80 at Kearney, Nebraska

Entrance to the Archway

Greeter at the Archway

Nebraska's Second Longest Escalator

Fort Kearny

Pushing a Wagon - Part of Women's Tasks Along the Trail

Driving the Oxen Team

Rock Cliff

Mormon Winter Scene

Pioneer Campfire Scene

Saying Goodbye to a Loved One and a Fallen Wagon

Pony Express Sign

Soldier Meeting with Two Pawnees at the Time of Building the Transcontinental Railroad

Traveling by Stagecoach

Part of Lincoln Highway Exhibit

Note: United States Tires Billboard

Note: United States Tires Billboard

Camping Scene with Model T

Kozy Kabins Camping Scene Along Lincoln Highway

Classic Oldsmobile Alongside Lincoln Highway Marker

Lincoln Highway Roadside Cafe

Waitress at Roadside Cafe