Hello Everyone,

When you think of forts during the American Revolution, the Ohio Territory is not an area that comes to mind. Yet, Fort Laurens, near Bolivar, Ohio, existed between 1778 and 1779. It’s the site of the Tomb of the Unknown Patriot of the Revolutionary War. The state also had the largest communal settlement in United States history. That occurred in Zoar, Ohio between the years of 1817 and 1898.

FORT LAURENS

During the summer of 1778, the Americans were succeeding in their struggle for independence from Great Britain. They had recently destroyed General Burgoyne’s entire army at Saratoga. However, west of the Alleghenies, it was a different story. The British had won over to their side all the Native Americans except for many of the Delaware Indians, who claimed neutrality yet supplied the Americans with information. Scattered pioneer settlements were subject to frequent attacks by the British and their Indian allies.

Fort Detroit (now Detroit) was British headquarters where 500 men were stationed. They were commanded by Henry Hamilton. The Indians favored the British because they supplied their needs whether it was blankets or alcohol. They did not like the Americans settling their lands and felt until the French became militarily involved that the British would be victorious.

Since April 10, 1777, Fort Pitt (now Pittsburgh) had been under the command of the American general Edward Hand. That November, a letter was sent by the vice president of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania to the Continental Congress detailing the West’s perils. Congress sent two representatives to a meeting at the fort to discuss the West’s problems, bring the Shawnee and Delaware chiefs to a council on July 23 to cement their friendship, and arrange for an expedition against Fort Detroit.

The Indian council met instead on September 17 with Delaware chiefs in attendance. A treaty was signed that allowed the Americans to cross Delaware lands. The Native Americans would also furnish wheat, corn, warriors, and guides. In exchange, the Americans would erect a fort in Delaware country, maintain the integrity of the Delaware Nation, and propose to Congress to make them a state.

Congress chose to raise two regiments to defend the frontier for a year. Twelve companies were from the Thirteenth Virginia and four from the Eighth Pennsylvania. John Gibson, a noted Indian fighter, was selected to command the Virginians while Colonel John Brodhead would lead the Pennsylvanians. The troops arrived at Fort Pitt on August 10.

General Hand was removed with General Washington appointing General Lachland McIntosh from Georgia. He had been suggested by Henry Laurens, president of the Continental Congress. McIntosh reciprocated by naming the fort after him.

Obtaining supplies and forage for the horses was difficult. Food had been scarce since January 1778 in the Fort Pitt area with residents refusing to bring it to the commissary. This meant food and equipment had to be requisitioned east of the Alleghenies and brought to Fort Pitt by packhorses. With supplies slow in arriving, the expedition against Fort Detroit was deferred. Instead McIntosh assembled 1,500 Continental troops to attack Indian towns on the Sandusky River, located a substantial distance from Detroit.

Before their march to create Fort Laurens, Colonel Brodhead had built a stockade, Fort McIntosh, located 20 miles downriver from Fort Pitt. He had moved most of the militia and continentals there. On October 25, McIntosh arrived only to be faced with delays in receiving supplies.

Finally, on November 4, 1,200 men left Fort McIntosh to head west. On November 7, Captain David Steel heard two shots and found two men from the Thirteenth Virginia had been scalped. The weakness of the packhorses was also discovered that day. Even though their loads were reduced by 100 pounds, they could only travel five miles a day.

On November 11, the weather was so severe that the men didn’t break camp. Groups of 13 men from each line were allowed to hunt. Their stores were improved by the arrival of Lt. Colonel Bowyer’s 69 men escorting packhorses and steers. On the 18th, they arrived on the banks of the Tuscarawas River, the future site of Fort Laurens. There the men would remain until they were allowed to return to Fort McIntosh.

A few days after the fort’s construction began, three companies of men were sent back to Fort McIntosh with all of the packhorses. Their mission was to load the animals with new supplies for the garrison. That meant that the soldiers who remained built a fort by chopping down trees then hauling them long distances strictly by their own manpower. They had no horses, mules, or oxen to assist their efforts. Construction supplies became scarce with no nails to make a sentry box or put doors on the huts. Suffering approximated that of Valley Forge the previous winter.

The fort was a stockade with two gates - one on the river side and one on the opposite side. It had temporary huts for the men. It had no artillery and would fail if large guns were used against it. John Gibson was in charge of the 152 men of the Thirteenth Virginia and 20 men of the Eighth Pennsylvania.

The fort was halfway between the Beaver and Sandusky Rivers and fulfilled the promise of a fort to the Delawares. The problem was it was too far north to provide protection for the Delawares. Its original purpose of a base for raiding Sandusky towns had been dropped. It quickly earned the name “Fort Nonsense.”

Provisions became rapidly exhausted as no more stores had arrived since Bowyer had overtaken the troops. Rations were four ounces of spoiled flour and eight ounces of unfit meat daily.

On January 19, David Zeisberger, a Moravian missionary who had converted many Delawares, warned Fort Laurens that the fort would be besieged about March 2. He warned that the British and their allies were gathering at Detroit and Sandusky.

On January 21, John Clark of the Eighth Pennsylvania brought clothes and whiskey to the soldiers at Fort Laurens. Gibson wrote a letter to Fort Pitt stating conditions at the fort were getting more and more desperate. On his return, Clark and his escort were three miles from the fort when they were ambushed and fired upon. They fired back, rounded up their wounded, and returned to the fort. Two were killed, four wounded, and one missing. The soldier carrying Gibson’s dispatch was taken prisoner. That letter made its way to the British.

At Fort Laurens, the supplies brought by Clark were seriously depleted by the middle of February. The work needed on the fort and the horrible Ohio winter pushed the small garrison to their physical limit. The troops needed food, clothing, and supplies in a hurry.

On February 8, McIntosh ordered Major Richard Taylor to deliver 200 kegs of flour, 50 barrels of beef and pork, whiskey, medicine, and other essentials to Fort Laurens. He never made it. His party returned to Fort Pitt without delivering supplies after receiving a warning about an impending attack.

The party of 180 British, Indians, and American renegades commanded by British captain Henry Bird had left Upper Sandusky and arrived at Fort Laurens totally undetected. They arrived on February 22 and surrounded the fort’s three land sides without being noticed by the defenders.

On February 23, unaware of the siege, Gibson sent a wagoner and 18 men to gather the horses that had strayed from the fort. This party was fired upon and 17 scalped within sight of the fort. Two were taken prisoners. One of which was never heard from again.

That evening the Indians, all in full war dress, made themselves visible. One of the men counted 847. The Indians created a deception where they went behind a knoll and came around without being recognized as repeaters. In actuality, they probably didn’t outnumber the 172 defenders.

Most of the men were terrified of leaving the fort. However, two men slipped out, killed a deer, and brought it back. It was eaten within minutes with many eating it raw. The situation was so desperate that they cooked the dried beef hides and some even roasted and ate their moccasins. Eventually, they were reduced to eating roots and herbs gathered a short distance from the fort.

The fort was not captured or surrendered as the enemy failed to press the attack. Before long, most of the Indians drifted back to Coshocton leaving three groups of twenty along the trail to Fort McIntosh to search for a relief party. The siege was finally raised around March 20.

General McIntosh learned of the situation when a Delaware Indian runner reached Fort Pitt on March 3 and advised him of the possibility of the assault by the British and Native Americans. McIntosh advised Colonel David Shepherd of the Virginia militia to be ready with two companies of 63 men to march to Fort Lauren’s relief. He also wrote the Delawares to reaffirm their friendship. Again, the late arrival of provisions and packhorses delayed the expedition until March 19. Five hundred men were rounded up. The relief party made the march in four days.

Upon arrival, the fort’s defenders rushed out and fired their muskets into the air in celebration. The packhorses became frightened, broke from their guides, and bolted into the woods throwing their loads to the ground and scattering their contents. Though the garrison and relief party combed the area for the rest of the day, they recovered only a small part of the supplies.

When McIntosh suggested attacking Sandusky, his officers immediately and unanimously rejected the idea. McIntosh’s dream of attacking Detroit was given up for good. In the spring, he asked for and received a transfer to a command in the Southern colonies.

Colonel Gibson and his garrison of about 150 men of the Thirteenth Virginia were relieved by Major Vernon and 106 men and officers from the Eighth Pennsylvania. McIntosh and his army returned to Fort Pitt.

On May 25, Big Cat, a reliable Delaware, wrote that in four days the British, Wyandots, Shawnees, and Mingoes would lay siege to the fort and destroy it by cannonading. The attack failed to occur when word reached the Indians that Captain John Bowman, lieutenant in the Kentucky militia, had led 300 volunteers to Chillicothe for a resounding “western” victory.

The Indians in Ohio rushed to protect their homes, and Fort Laurens was left alone. When they regained a serious interest in it, the fort had been deserted and the garrison was back at Fort Pitt.

Lieutenant Colonel Richard Campbell of the Thirteenth Virginia took over the post on July 15 with 75 men including a party from the Maryland Regiment. Vernon had been instructed to return all unnecessary stores to Fort Pitt. However, his packhorses were weakened by the heavy loads they had carried westward so they returned with only a few empty bags. On July 16, Campbell was told to vacate the fort as soon as the necessary packhorses to carry all the stores had arrived. He was told not to destroy the fort. Then the Delawares could use it as a shelter from other tribes.

Brodhead warned Ensign John Beck at Fort Laurens on August 1 about two parties of 20 hostile Indians moving in the direction of the Tuscarawas River. His warning did not reach the fort on time, and two soldiers were killed within sight of their comrades at the fort. They were the final two men killed. The troops left Fort Laurens for good on August 2 and arrived at Fort Pitt on August 7.

By the 1830's, the fort had seriously deteriorated due to weather, natural decay, farmers’ plows, and the use of wood from the fort. In 1832, the building of the Ohio & Erie Canal at Fort Laurens substantially destroyed its two eastern bastions. Being a wooden fort, when the wood rotted, it left a footprint on the ground. That is how archeologists found the location of the fort’s buildings and its outline. You can see part of that footprint today.

FORT LAURENS MUSEUM

In 1968, the Ohio Historical Society proposed a bond issue to provide capital improvements to Fort Laurens. It was approved. The dedication of a visitor center took place on May 18, 1974. The circular museum has an auditorium in the center. Its 20-minute video depicts the fort’s history and the building of the visitor center.

The exhibit in the theater room depicts the archeology excavations which occurred in 1972 and 1973. On the bottom level, one can see a clay pipe, metal spoon, flintlock, belt buckle, and primitive tools. The top level of this exhibit represents excavation 100 years from now with a coil, pull tab, and a glass bottle. You will also find a model of the fort in the theater.

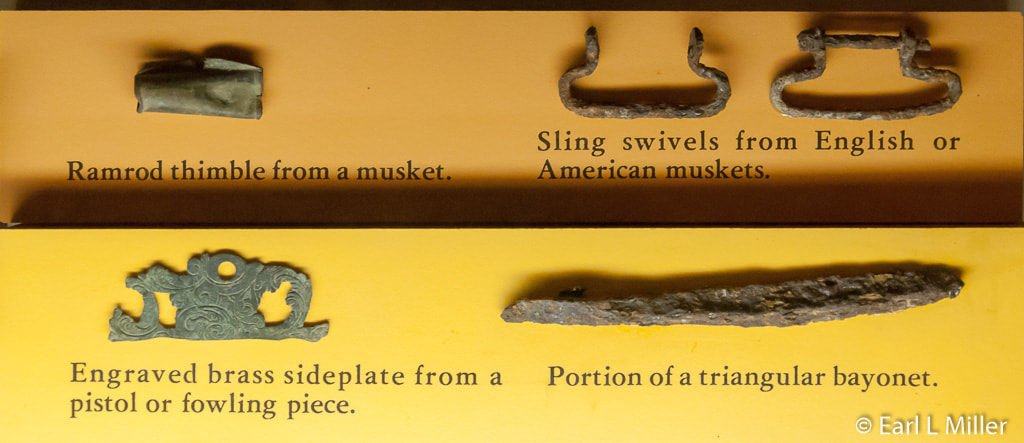

Most of the exhibits are around the theater’s periphery. You will see in some cases many of the excavated objects - an iron kettle, glass bottle, Virginia halfpenny, deer and horse bones, a clay pipe, scissors, gunflints, buttons, and knee and shoe buckles. You’ll probably also spot hand wrought nails and spikes, a Jew’s harp, and some of the chinking they used between logs. In other cases, you’ll see Continental currency and wooden canteens, bayonets, muskets, and a bow and arrow. Dioramas depict soldiers wearing the uniforms of the various regiments.

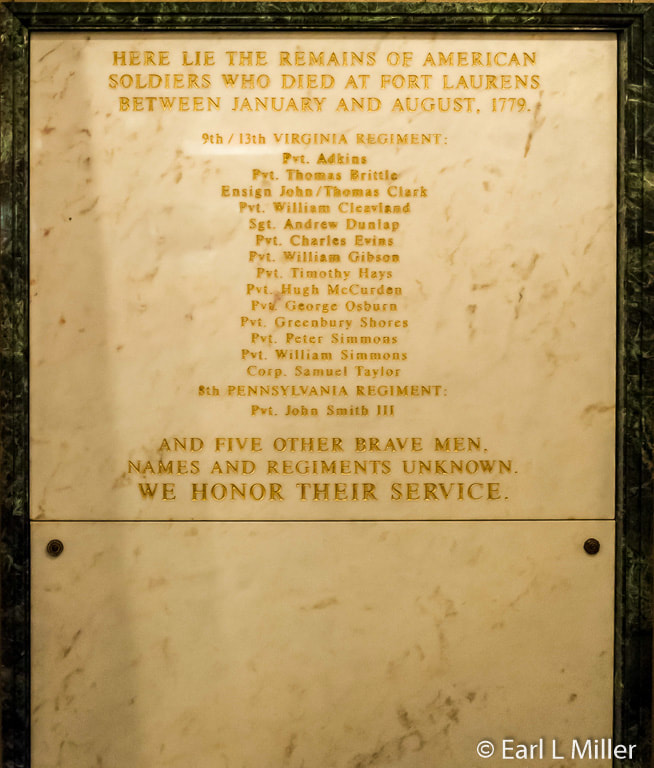

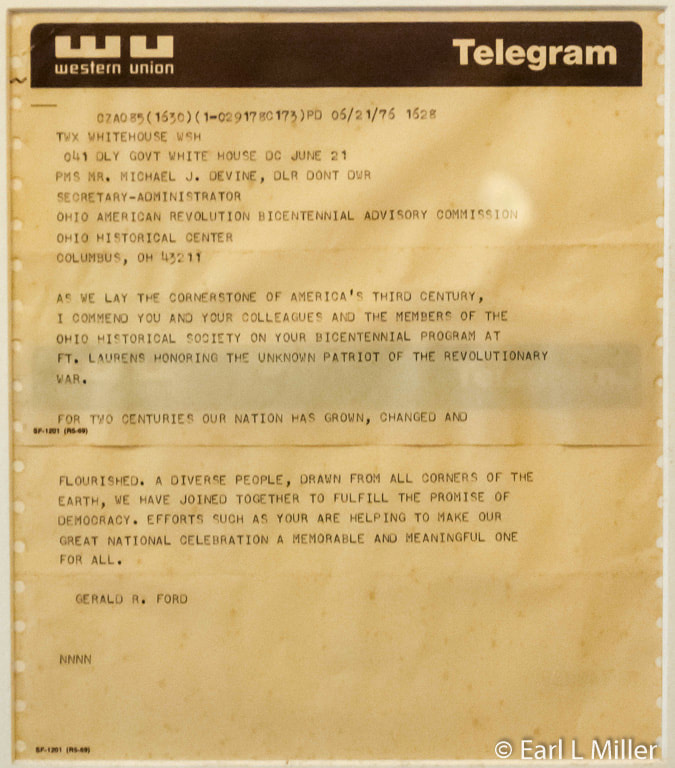

You will see a crypt where 15 known and five unknown soldiers were reinterred. Outside the museum is the Tomb of the Unknown Patriot of the Revolutionary War that was dedicated in 1976. The only other unknown revolutionary soldier is in Philadelphia. The museum displays a telegram from President Ford regarding the crypt’s dedication at Fort Laurens.

DETAILS

Fort Laurens is at 11067 Fort Laurens Road NW, Bolivar, Ohio. The telephone number is (330) 874-2059. Fort Laurens is open on weekends from May through October. Saturday hours are from 11:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. while Sunday hours are from noon to 4:00 p.m. From June to August, they are also open Wednesday through Friday 11:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. In September, it’s Fridays and weekends with the same hours as the other months. Admission is $5 for those 18 years and older and $3 for ages 5-17. Admission is free for active duty families.

ZOAR

Serving as a communal society from 1819 to 1898, Zoar, Ohio holds the record for the longest lasting communal society in the United States. During the middle 1800's, it was a popular stop on the Ohio & Erie Canal. Today its 12 block historic area, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, serves the needs of approximately 170 town residents. Some of the historic buildings are private homes. Others are open from April through October for group and individual tours.

Those who settled Zoar were called Separatists. They emigrated from the kingdom of Württemberg in Southwest Germany where they had suffered persecution with fines, confiscation of their property, and imprisonment because they refused to follow the state run Lutheran religion. Since they didn’t practice baptism or confirmation, celebrate religious holidays except for the Sabbath, and chose not to have a minister, they believed they had to separate from Germany’s religion hence their name.

They didn’t attend a formal church but met in private homes. In Rottenacker, they were forced to house soldiers in their homes at their own expense. Being pacifists, they felt it was intolerable.

Some traveled to America in 1804. In 1807, King Friedrich forbid such emigration and arrested some of the Separatist leaders. The group then stayed underground for the next decade.

In 1817, aided by Quakers from Northern Germany and London, the Separatists from two dozen villages around Stuttgart, Germany, led by Joseph Bimeler, made their way to Antwerp, Belgium. There they boarded the ship, the Vaterlandsliebe, for a four-month journey to America.

European Quakers had advised those in Philadelphia that the group would be arriving. When the American Quakers met the ship, they provided food and lodging and helped the Separatists find jobs. Some became maids or laborers for Quaker families. They also lent the Separatists $16,500 so they could purchase 5,000 acres of land in Ohio. Several members of the group headed to what is now Zoar in 1817 to construct the first buildings. The rest of the Separatists, approximately 200, arrived during the spring of 1818.

They did not have a communal society at first since they planned to individually farm their new Ohio land. However, it proved too difficult since they had old and feeble people, several who were poor, an inadequate labor force, and an unfriendly frontier. Led by Johannes Breymaier, some suggested creating a community where all labor and the resulting wealth would be shared equally among the group’s members. In return, all would be supplied with food, clothing, and shelter. On August 15, 1819, all women aged 18 and older and all men aged 21 and older signed an agreement forming the Society of Separatists of Zoar. The title of all property was held in Bimeler’s name until ten days before his death August 27, 1853. Then he willed it to the Society.

The agreement meant that each member gave up all of his or her money and property including any future inheritance. Those who left the Society didn’t receive any money or property back or payments for the labor they had contributed.

The community became celibate in 1822 enabling the women to work full time. Women now had equal status to men. They could vote in Zoar one hundred years before women did so nationwide. Women in Zoar could hold public office though none of them did. They incorporated under Ohio laws on February 3, 1832 and adopted a constitution on May 14, 1833.

In Zoar, they first met at Joseph Bimeler’s home, a log cabin, that functioned as a meetinghouse. He spoke on religious and secular topics. The service included silent prayers and singing of psalms accompanied by musicians. The center of their beliefs was a quest to be more Christlike and be born again through him. They refused to let ceremonies or the clergy overshadow their relationship with God.

The second Meeting House did not survive. The third is composed of bricks made in Zoar and stone hewn in the Separatists’ quarries. After the Society was dissolved, the church stood silent until the Evangelical Church took it over in 1901. The interior has changed very little and seats one hundred people. It has a pipe organ used for regular services and a bell composed of melted silver dollars mixed with ore. The bell has an unusual sound which still rings every Sunday.

Contractors hired people to build the Ohio & Erie Canal of which a seven-mile segment ran through the Society’s land. The Separatists acquired a contract to construct that portion of the canal and to build three canal locks between Bolivar and Zoar. Men and women provided the labor. The men did the digging while the women carried numerous tubs of heavy soil, sometimes on their heads, away from the dig site. The Separatists received $21,000 in 1828 allowing them to pay off the loan to purchase their land and to end celibacy as soon as 1829.

The Society owned three canal boats. Their use allowed Zoar to market its crops more widely, bring in visitors, and develop an iron industry. Soon after the Ohio & Erie Canal opened, the Separatists built the Canal Tavern, originally named the Canawler’s Inn, which still caters to patrons today. In 1833, they built the Zoar hotel in town to house canal boat passengers.

The canal and towpath the Separatists built is known today as the Towpath Trail. It runs from Cleveland to New Philadelphia and is a multiuse trail. It’s been established by the United States Congress as a National Historic Corridor.

Farming had been their main industry in Germany, and agriculture continued to be the backbone for Zoar. The Society had such abundant crops and livestock that it not only provided for them and the hotel, but surplus was sold to others along the canal. Their main crops were wheat, barley (for beer), oats, corn, and rye. Most of the farmwork was by hand although they did use mechanical reapers and other equipment. All Society members participated in the harvest which was celebrated when the last load of wheat arrived at the granary.

The Society owned mills that ground wheat into flour. Since the mills served nearby farmers, it was another source of income for Zoar.

Dairy cows, beef cattle, and sheep were raised for meat and for sale. The Society’s woolen mills and tannery used the wool and hides. Pigs weren’t initially raised since the Separatists viewed pork as unclean. Each household had its own vegetable and kitchen gardens located near their homes. Potatoes and onions were planted communally for all to share.

Zoar industries were also profitable. They included two iron furnaces, a church, bakery, tin shop, blacksmith shop, cabinetmaker, brewmaster, weaving and sewing houses, a pottery, a tannery, and cider and grain mills, What they could not use themselves, they sold to visitors and to others outside the village. The village also contained a greenhouse, a town hall, a meetinghouse, a hotel, and private and communal residences.

In August 1834, the society was hit by a month long cholera epidemic where 56 people died, nearly one third of the village’s population. Deaths occurred so rapidly that the cabinetmaker could not build coffins fast enough. Because of the number of deaths, a labor shortage occurred that forced the Society to hire outsiders to work in its fields and industries.

After Bimeler died in 1853, Zoar remained economically prosperous. However, the commitment for a communal society began to die in the second half of the 19th century. Many of the original residents had died, and the younger ones did not recall the persecution suffered in Germany. The visitors who stayed at the hotel influenced the Society’s members into thinking they could have a better kind of life that wasn’t communal. In 1898, the remaining members dissolved the society and divided the property among themselves. Zoar continues today as a small town where tours can be obtained of the historic area.

Most of the museum buildings are from the 1800s. The Tin Shop. Wagon Shop, and Blacksmith Shop were reconstructed in the 1970's but are located on the sites of the original structures. The first to open as museums were the Bimeler House in the 1920's and No. 1 House in the 1930's.

TODAY IN ZOAR

The Ohio Historical Society and the Zoar Community Association manage several of Zoar’s public buildings providing interpretative tours and demonstrations. The community holds special events throughout the year ranging from seasonal festivals to ones for students to classes for adults. A complete list of these is available on their web site.

During special events, many demonstrations take place. These include tinsmithing in the Tin Shop where they make objects like candle holders; butter churning or ice cream making in the Dairy; cooking demonstrations in the Kitchen; spinning in the No. 1 House; laundry demonstrations in the Laundry; rug weaving or hooking in the Sewing House; carpentry in the Wagon Shop; and bread, pretzel, or cooking and baking demonstrations in the Bakery.

Zoar also offers many classes throughout the year. Blacksmithing classes run on many Saturdays from April through October. Needlepoint, basic dough, pretzel and watercolor classes are offered multiple times throughout the year. Zoar offers rug weaving classes by appointment and is currently working on providing a basic German course and a basket weaving course in 2018.

Some of the major events are the annual Maifest and a biannual Garden Tour (June 16) which alternates with the Civil War Reenactment (September 21 and 22 next year.) In the past, they have had more than 500 reenactors participate. Ghost tours are held the last two weekends of every October. In July, Kids’ History Camps and Adult History Camps take place at Zoar and their sister attraction, Fort Laurens.

TOUR HIGHLIGHTS

To tour the village’s historic buildings, start at the Zoar Store and Visitor Center. Built across from the hotel in 1833, it served as the business headquarters for the Society, the post office, and a store. Since the Society’s members had no cash, they were able to purchase items from the store based on labor given to the society. Hired help and farmers in the surrounding territory paid cash. An addition at the rear of the store served as a dairy. In 2018, it is a gift shop, information center, and the place to obtain tickets for self guided or guided tours.

On private guided tours, visitors see four to five buildings in a two-hour time period. The standard ones are usually the Town Hall, the No. 1 House, the Garden House, and The Bakery. Guests can request to see other buildings that fit their interests. For regular, self guided tours, visitors also find the Magazine (storehouse) and Bimeler House and Art Gallery open. The Blacksmith Shop is occasionally open on Fridays and Sundays, but always open on Saturdays during self-guided hours and during special events.

Once the hub of community life, the town hall has served as Zoar’s post office and fire department as well as the Saturday night hall. The Society barbershop was located here, and it was where the Zoar band practiced. It now serves as the local government chambers in the lower level and is the home of two museums. One has many artifacts related to Zoar industries ranging from tools to examples of fabric the women sewed. The other is on the Ohio & Erie canal with model canal boats and canal-related objects. Visitors can also watch a short video on Zoar history.

The No. 1 House was built in 1835. It was intended as a residence for the elderly Society members. However, it became the home for Joseph Bimeler’s family as well as the other two Society trustees and their families. Opened as a museum in 1935, it contains Zoar artifacts ranging from clothing and tools to pottery and more. Its dining room, kitchen, and magazine (for dry good storage) are part of the tour.

Visitors also find lots of signage on topics pertaining to Zoar’s communal history. These cover the canal, agriculture, how the society was formed, industry, and tourism. Look for the excellent time line covering events from the Separatists start in Germany to modern times.

You will want to look for the society’s symbol of the seven-pointed star at the ceiling above the stairs. It was designed by Joseph Bimeler. It represents the inner light of Christ and was worn like a badge of honor to proclaim a person’s adherence to the Separatist creed.

The third museum is the Bimeler Museum and Art Gallery dated 1868. It was once the home of William and Lillian Bimeler. In 2013, a flood lifted the building off of its foundation. It reopened in May 2017 and now houses beautiful artwork in several rooms.

We saw a temporary exhibit of paintings and watercolors depicting the village and its surrounding countryside by artists from the Cleveland School of Art. One room was devoted to August Biehle’s artwork. He visited Zoar for almost 40 years. We also viewed paintings by George Adomeit, Tomas Maier, and Joseph Jicha who interpreted Zoar in a more artistic fashion. This museum has no admission.

The Garden House was the home of Simon Beuter, the Society’s gardener, and his family. There is one greenhouse on the property. Covering an acre of ground, the large Norway spruce tree in the garden’s center depicts everlasting life. It is circled by a hedge of Arbor Vitae. Outside the green path circling the hedge are twelve Irish juniper trees representing the twelve apostles. The paths symbolize the different paths to heaven radiating from the garden’s center.

Another tour spot is The Bakery dated 1845. It was known for its bread, buns, and gingerbread. You can still purchase baked goods today from June through September on Friday and Saturday 11:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. and Sunday from noon to 4:00 p.m.

The Zoar Hotel is one of the spots explored during Zoar Ghost Tours. It had 40 sleeping rooms and a very large dining room. It accommodated everyone from beggars to President William McKinley. Known for its food and lodging, it was a hotel until 1953.

To learn about village buildings such as the church, assembly house, and school, take a virtual tour of their web site. Clicking on each of the buildings provides the historical significance of each structure.

There are four places to eat. Canal Street Diner serves casual food. Canal Tavern of Zoar features fine American and German cuisine in the former 1829 Canawler Inn. Firehouse Grille & Pub, in the #23 house, the former home of the town doctor, has casual American dining. Simply Cinnamon is a local deli and café.

The village also offers bed and breakfasts with historical ties. Keeping Room Bed and Breakfast was the former home of Zoar’s treasurer. It was built in 1877. The Cobbler Shop Bed and Breakfast is housed in an historic home full of antiques dating to 1828. The owners run one of four village antique shops. The 1863 Cider Mill is home to Crafting Retreat. The Zoar School Inn Bed & Breakfast was the schoolhouse in 1836 serving that function until 1868.

DETAILS

It is necessary to purchase a wristband at the Zoar store at 198 Main Street to tour the historic buildings. The phone number is (330) 874-3011. Price is $8 for adults (18+) and $4 for a child (ages 5-17.) Zoar is closed from November through March. During the rest of the year, it is open on Saturdays from 11:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. and on Sundays, noon to 4:00 p.m. During the summer season, June through September, it is also open Wednesday through Friday with the hours the same as Saturday’s.

Combination tickets with Fort Laurens are $10 for adults (18+) and $5 for children (ages 5-17). They are available at either Zoar or Fort Laurens. The two tickets must be used the same day. I recommend going to Fort Laurens first for 1-1/2 hours then spending the rest of the day at Zoar.

When you think of forts during the American Revolution, the Ohio Territory is not an area that comes to mind. Yet, Fort Laurens, near Bolivar, Ohio, existed between 1778 and 1779. It’s the site of the Tomb of the Unknown Patriot of the Revolutionary War. The state also had the largest communal settlement in United States history. That occurred in Zoar, Ohio between the years of 1817 and 1898.

FORT LAURENS

During the summer of 1778, the Americans were succeeding in their struggle for independence from Great Britain. They had recently destroyed General Burgoyne’s entire army at Saratoga. However, west of the Alleghenies, it was a different story. The British had won over to their side all the Native Americans except for many of the Delaware Indians, who claimed neutrality yet supplied the Americans with information. Scattered pioneer settlements were subject to frequent attacks by the British and their Indian allies.

Fort Detroit (now Detroit) was British headquarters where 500 men were stationed. They were commanded by Henry Hamilton. The Indians favored the British because they supplied their needs whether it was blankets or alcohol. They did not like the Americans settling their lands and felt until the French became militarily involved that the British would be victorious.

Since April 10, 1777, Fort Pitt (now Pittsburgh) had been under the command of the American general Edward Hand. That November, a letter was sent by the vice president of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania to the Continental Congress detailing the West’s perils. Congress sent two representatives to a meeting at the fort to discuss the West’s problems, bring the Shawnee and Delaware chiefs to a council on July 23 to cement their friendship, and arrange for an expedition against Fort Detroit.

The Indian council met instead on September 17 with Delaware chiefs in attendance. A treaty was signed that allowed the Americans to cross Delaware lands. The Native Americans would also furnish wheat, corn, warriors, and guides. In exchange, the Americans would erect a fort in Delaware country, maintain the integrity of the Delaware Nation, and propose to Congress to make them a state.

Congress chose to raise two regiments to defend the frontier for a year. Twelve companies were from the Thirteenth Virginia and four from the Eighth Pennsylvania. John Gibson, a noted Indian fighter, was selected to command the Virginians while Colonel John Brodhead would lead the Pennsylvanians. The troops arrived at Fort Pitt on August 10.

General Hand was removed with General Washington appointing General Lachland McIntosh from Georgia. He had been suggested by Henry Laurens, president of the Continental Congress. McIntosh reciprocated by naming the fort after him.

Obtaining supplies and forage for the horses was difficult. Food had been scarce since January 1778 in the Fort Pitt area with residents refusing to bring it to the commissary. This meant food and equipment had to be requisitioned east of the Alleghenies and brought to Fort Pitt by packhorses. With supplies slow in arriving, the expedition against Fort Detroit was deferred. Instead McIntosh assembled 1,500 Continental troops to attack Indian towns on the Sandusky River, located a substantial distance from Detroit.

Before their march to create Fort Laurens, Colonel Brodhead had built a stockade, Fort McIntosh, located 20 miles downriver from Fort Pitt. He had moved most of the militia and continentals there. On October 25, McIntosh arrived only to be faced with delays in receiving supplies.

Finally, on November 4, 1,200 men left Fort McIntosh to head west. On November 7, Captain David Steel heard two shots and found two men from the Thirteenth Virginia had been scalped. The weakness of the packhorses was also discovered that day. Even though their loads were reduced by 100 pounds, they could only travel five miles a day.

On November 11, the weather was so severe that the men didn’t break camp. Groups of 13 men from each line were allowed to hunt. Their stores were improved by the arrival of Lt. Colonel Bowyer’s 69 men escorting packhorses and steers. On the 18th, they arrived on the banks of the Tuscarawas River, the future site of Fort Laurens. There the men would remain until they were allowed to return to Fort McIntosh.

A few days after the fort’s construction began, three companies of men were sent back to Fort McIntosh with all of the packhorses. Their mission was to load the animals with new supplies for the garrison. That meant that the soldiers who remained built a fort by chopping down trees then hauling them long distances strictly by their own manpower. They had no horses, mules, or oxen to assist their efforts. Construction supplies became scarce with no nails to make a sentry box or put doors on the huts. Suffering approximated that of Valley Forge the previous winter.

The fort was a stockade with two gates - one on the river side and one on the opposite side. It had temporary huts for the men. It had no artillery and would fail if large guns were used against it. John Gibson was in charge of the 152 men of the Thirteenth Virginia and 20 men of the Eighth Pennsylvania.

The fort was halfway between the Beaver and Sandusky Rivers and fulfilled the promise of a fort to the Delawares. The problem was it was too far north to provide protection for the Delawares. Its original purpose of a base for raiding Sandusky towns had been dropped. It quickly earned the name “Fort Nonsense.”

Provisions became rapidly exhausted as no more stores had arrived since Bowyer had overtaken the troops. Rations were four ounces of spoiled flour and eight ounces of unfit meat daily.

On January 19, David Zeisberger, a Moravian missionary who had converted many Delawares, warned Fort Laurens that the fort would be besieged about March 2. He warned that the British and their allies were gathering at Detroit and Sandusky.

On January 21, John Clark of the Eighth Pennsylvania brought clothes and whiskey to the soldiers at Fort Laurens. Gibson wrote a letter to Fort Pitt stating conditions at the fort were getting more and more desperate. On his return, Clark and his escort were three miles from the fort when they were ambushed and fired upon. They fired back, rounded up their wounded, and returned to the fort. Two were killed, four wounded, and one missing. The soldier carrying Gibson’s dispatch was taken prisoner. That letter made its way to the British.

At Fort Laurens, the supplies brought by Clark were seriously depleted by the middle of February. The work needed on the fort and the horrible Ohio winter pushed the small garrison to their physical limit. The troops needed food, clothing, and supplies in a hurry.

On February 8, McIntosh ordered Major Richard Taylor to deliver 200 kegs of flour, 50 barrels of beef and pork, whiskey, medicine, and other essentials to Fort Laurens. He never made it. His party returned to Fort Pitt without delivering supplies after receiving a warning about an impending attack.

The party of 180 British, Indians, and American renegades commanded by British captain Henry Bird had left Upper Sandusky and arrived at Fort Laurens totally undetected. They arrived on February 22 and surrounded the fort’s three land sides without being noticed by the defenders.

On February 23, unaware of the siege, Gibson sent a wagoner and 18 men to gather the horses that had strayed from the fort. This party was fired upon and 17 scalped within sight of the fort. Two were taken prisoners. One of which was never heard from again.

That evening the Indians, all in full war dress, made themselves visible. One of the men counted 847. The Indians created a deception where they went behind a knoll and came around without being recognized as repeaters. In actuality, they probably didn’t outnumber the 172 defenders.

Most of the men were terrified of leaving the fort. However, two men slipped out, killed a deer, and brought it back. It was eaten within minutes with many eating it raw. The situation was so desperate that they cooked the dried beef hides and some even roasted and ate their moccasins. Eventually, they were reduced to eating roots and herbs gathered a short distance from the fort.

The fort was not captured or surrendered as the enemy failed to press the attack. Before long, most of the Indians drifted back to Coshocton leaving three groups of twenty along the trail to Fort McIntosh to search for a relief party. The siege was finally raised around March 20.

General McIntosh learned of the situation when a Delaware Indian runner reached Fort Pitt on March 3 and advised him of the possibility of the assault by the British and Native Americans. McIntosh advised Colonel David Shepherd of the Virginia militia to be ready with two companies of 63 men to march to Fort Lauren’s relief. He also wrote the Delawares to reaffirm their friendship. Again, the late arrival of provisions and packhorses delayed the expedition until March 19. Five hundred men were rounded up. The relief party made the march in four days.

Upon arrival, the fort’s defenders rushed out and fired their muskets into the air in celebration. The packhorses became frightened, broke from their guides, and bolted into the woods throwing their loads to the ground and scattering their contents. Though the garrison and relief party combed the area for the rest of the day, they recovered only a small part of the supplies.

When McIntosh suggested attacking Sandusky, his officers immediately and unanimously rejected the idea. McIntosh’s dream of attacking Detroit was given up for good. In the spring, he asked for and received a transfer to a command in the Southern colonies.

Colonel Gibson and his garrison of about 150 men of the Thirteenth Virginia were relieved by Major Vernon and 106 men and officers from the Eighth Pennsylvania. McIntosh and his army returned to Fort Pitt.

On May 25, Big Cat, a reliable Delaware, wrote that in four days the British, Wyandots, Shawnees, and Mingoes would lay siege to the fort and destroy it by cannonading. The attack failed to occur when word reached the Indians that Captain John Bowman, lieutenant in the Kentucky militia, had led 300 volunteers to Chillicothe for a resounding “western” victory.

The Indians in Ohio rushed to protect their homes, and Fort Laurens was left alone. When they regained a serious interest in it, the fort had been deserted and the garrison was back at Fort Pitt.

Lieutenant Colonel Richard Campbell of the Thirteenth Virginia took over the post on July 15 with 75 men including a party from the Maryland Regiment. Vernon had been instructed to return all unnecessary stores to Fort Pitt. However, his packhorses were weakened by the heavy loads they had carried westward so they returned with only a few empty bags. On July 16, Campbell was told to vacate the fort as soon as the necessary packhorses to carry all the stores had arrived. He was told not to destroy the fort. Then the Delawares could use it as a shelter from other tribes.

Brodhead warned Ensign John Beck at Fort Laurens on August 1 about two parties of 20 hostile Indians moving in the direction of the Tuscarawas River. His warning did not reach the fort on time, and two soldiers were killed within sight of their comrades at the fort. They were the final two men killed. The troops left Fort Laurens for good on August 2 and arrived at Fort Pitt on August 7.

By the 1830's, the fort had seriously deteriorated due to weather, natural decay, farmers’ plows, and the use of wood from the fort. In 1832, the building of the Ohio & Erie Canal at Fort Laurens substantially destroyed its two eastern bastions. Being a wooden fort, when the wood rotted, it left a footprint on the ground. That is how archeologists found the location of the fort’s buildings and its outline. You can see part of that footprint today.

FORT LAURENS MUSEUM

In 1968, the Ohio Historical Society proposed a bond issue to provide capital improvements to Fort Laurens. It was approved. The dedication of a visitor center took place on May 18, 1974. The circular museum has an auditorium in the center. Its 20-minute video depicts the fort’s history and the building of the visitor center.

The exhibit in the theater room depicts the archeology excavations which occurred in 1972 and 1973. On the bottom level, one can see a clay pipe, metal spoon, flintlock, belt buckle, and primitive tools. The top level of this exhibit represents excavation 100 years from now with a coil, pull tab, and a glass bottle. You will also find a model of the fort in the theater.

Most of the exhibits are around the theater’s periphery. You will see in some cases many of the excavated objects - an iron kettle, glass bottle, Virginia halfpenny, deer and horse bones, a clay pipe, scissors, gunflints, buttons, and knee and shoe buckles. You’ll probably also spot hand wrought nails and spikes, a Jew’s harp, and some of the chinking they used between logs. In other cases, you’ll see Continental currency and wooden canteens, bayonets, muskets, and a bow and arrow. Dioramas depict soldiers wearing the uniforms of the various regiments.

You will see a crypt where 15 known and five unknown soldiers were reinterred. Outside the museum is the Tomb of the Unknown Patriot of the Revolutionary War that was dedicated in 1976. The only other unknown revolutionary soldier is in Philadelphia. The museum displays a telegram from President Ford regarding the crypt’s dedication at Fort Laurens.

DETAILS

Fort Laurens is at 11067 Fort Laurens Road NW, Bolivar, Ohio. The telephone number is (330) 874-2059. Fort Laurens is open on weekends from May through October. Saturday hours are from 11:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. while Sunday hours are from noon to 4:00 p.m. From June to August, they are also open Wednesday through Friday 11:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. In September, it’s Fridays and weekends with the same hours as the other months. Admission is $5 for those 18 years and older and $3 for ages 5-17. Admission is free for active duty families.

ZOAR

Serving as a communal society from 1819 to 1898, Zoar, Ohio holds the record for the longest lasting communal society in the United States. During the middle 1800's, it was a popular stop on the Ohio & Erie Canal. Today its 12 block historic area, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, serves the needs of approximately 170 town residents. Some of the historic buildings are private homes. Others are open from April through October for group and individual tours.

Those who settled Zoar were called Separatists. They emigrated from the kingdom of Württemberg in Southwest Germany where they had suffered persecution with fines, confiscation of their property, and imprisonment because they refused to follow the state run Lutheran religion. Since they didn’t practice baptism or confirmation, celebrate religious holidays except for the Sabbath, and chose not to have a minister, they believed they had to separate from Germany’s religion hence their name.

They didn’t attend a formal church but met in private homes. In Rottenacker, they were forced to house soldiers in their homes at their own expense. Being pacifists, they felt it was intolerable.

Some traveled to America in 1804. In 1807, King Friedrich forbid such emigration and arrested some of the Separatist leaders. The group then stayed underground for the next decade.

In 1817, aided by Quakers from Northern Germany and London, the Separatists from two dozen villages around Stuttgart, Germany, led by Joseph Bimeler, made their way to Antwerp, Belgium. There they boarded the ship, the Vaterlandsliebe, for a four-month journey to America.

European Quakers had advised those in Philadelphia that the group would be arriving. When the American Quakers met the ship, they provided food and lodging and helped the Separatists find jobs. Some became maids or laborers for Quaker families. They also lent the Separatists $16,500 so they could purchase 5,000 acres of land in Ohio. Several members of the group headed to what is now Zoar in 1817 to construct the first buildings. The rest of the Separatists, approximately 200, arrived during the spring of 1818.

They did not have a communal society at first since they planned to individually farm their new Ohio land. However, it proved too difficult since they had old and feeble people, several who were poor, an inadequate labor force, and an unfriendly frontier. Led by Johannes Breymaier, some suggested creating a community where all labor and the resulting wealth would be shared equally among the group’s members. In return, all would be supplied with food, clothing, and shelter. On August 15, 1819, all women aged 18 and older and all men aged 21 and older signed an agreement forming the Society of Separatists of Zoar. The title of all property was held in Bimeler’s name until ten days before his death August 27, 1853. Then he willed it to the Society.

The agreement meant that each member gave up all of his or her money and property including any future inheritance. Those who left the Society didn’t receive any money or property back or payments for the labor they had contributed.

The community became celibate in 1822 enabling the women to work full time. Women now had equal status to men. They could vote in Zoar one hundred years before women did so nationwide. Women in Zoar could hold public office though none of them did. They incorporated under Ohio laws on February 3, 1832 and adopted a constitution on May 14, 1833.

In Zoar, they first met at Joseph Bimeler’s home, a log cabin, that functioned as a meetinghouse. He spoke on religious and secular topics. The service included silent prayers and singing of psalms accompanied by musicians. The center of their beliefs was a quest to be more Christlike and be born again through him. They refused to let ceremonies or the clergy overshadow their relationship with God.

The second Meeting House did not survive. The third is composed of bricks made in Zoar and stone hewn in the Separatists’ quarries. After the Society was dissolved, the church stood silent until the Evangelical Church took it over in 1901. The interior has changed very little and seats one hundred people. It has a pipe organ used for regular services and a bell composed of melted silver dollars mixed with ore. The bell has an unusual sound which still rings every Sunday.

Contractors hired people to build the Ohio & Erie Canal of which a seven-mile segment ran through the Society’s land. The Separatists acquired a contract to construct that portion of the canal and to build three canal locks between Bolivar and Zoar. Men and women provided the labor. The men did the digging while the women carried numerous tubs of heavy soil, sometimes on their heads, away from the dig site. The Separatists received $21,000 in 1828 allowing them to pay off the loan to purchase their land and to end celibacy as soon as 1829.

The Society owned three canal boats. Their use allowed Zoar to market its crops more widely, bring in visitors, and develop an iron industry. Soon after the Ohio & Erie Canal opened, the Separatists built the Canal Tavern, originally named the Canawler’s Inn, which still caters to patrons today. In 1833, they built the Zoar hotel in town to house canal boat passengers.

The canal and towpath the Separatists built is known today as the Towpath Trail. It runs from Cleveland to New Philadelphia and is a multiuse trail. It’s been established by the United States Congress as a National Historic Corridor.

Farming had been their main industry in Germany, and agriculture continued to be the backbone for Zoar. The Society had such abundant crops and livestock that it not only provided for them and the hotel, but surplus was sold to others along the canal. Their main crops were wheat, barley (for beer), oats, corn, and rye. Most of the farmwork was by hand although they did use mechanical reapers and other equipment. All Society members participated in the harvest which was celebrated when the last load of wheat arrived at the granary.

The Society owned mills that ground wheat into flour. Since the mills served nearby farmers, it was another source of income for Zoar.

Dairy cows, beef cattle, and sheep were raised for meat and for sale. The Society’s woolen mills and tannery used the wool and hides. Pigs weren’t initially raised since the Separatists viewed pork as unclean. Each household had its own vegetable and kitchen gardens located near their homes. Potatoes and onions were planted communally for all to share.

Zoar industries were also profitable. They included two iron furnaces, a church, bakery, tin shop, blacksmith shop, cabinetmaker, brewmaster, weaving and sewing houses, a pottery, a tannery, and cider and grain mills, What they could not use themselves, they sold to visitors and to others outside the village. The village also contained a greenhouse, a town hall, a meetinghouse, a hotel, and private and communal residences.

In August 1834, the society was hit by a month long cholera epidemic where 56 people died, nearly one third of the village’s population. Deaths occurred so rapidly that the cabinetmaker could not build coffins fast enough. Because of the number of deaths, a labor shortage occurred that forced the Society to hire outsiders to work in its fields and industries.

After Bimeler died in 1853, Zoar remained economically prosperous. However, the commitment for a communal society began to die in the second half of the 19th century. Many of the original residents had died, and the younger ones did not recall the persecution suffered in Germany. The visitors who stayed at the hotel influenced the Society’s members into thinking they could have a better kind of life that wasn’t communal. In 1898, the remaining members dissolved the society and divided the property among themselves. Zoar continues today as a small town where tours can be obtained of the historic area.

Most of the museum buildings are from the 1800s. The Tin Shop. Wagon Shop, and Blacksmith Shop were reconstructed in the 1970's but are located on the sites of the original structures. The first to open as museums were the Bimeler House in the 1920's and No. 1 House in the 1930's.

TODAY IN ZOAR

The Ohio Historical Society and the Zoar Community Association manage several of Zoar’s public buildings providing interpretative tours and demonstrations. The community holds special events throughout the year ranging from seasonal festivals to ones for students to classes for adults. A complete list of these is available on their web site.

During special events, many demonstrations take place. These include tinsmithing in the Tin Shop where they make objects like candle holders; butter churning or ice cream making in the Dairy; cooking demonstrations in the Kitchen; spinning in the No. 1 House; laundry demonstrations in the Laundry; rug weaving or hooking in the Sewing House; carpentry in the Wagon Shop; and bread, pretzel, or cooking and baking demonstrations in the Bakery.

Zoar also offers many classes throughout the year. Blacksmithing classes run on many Saturdays from April through October. Needlepoint, basic dough, pretzel and watercolor classes are offered multiple times throughout the year. Zoar offers rug weaving classes by appointment and is currently working on providing a basic German course and a basket weaving course in 2018.

Some of the major events are the annual Maifest and a biannual Garden Tour (June 16) which alternates with the Civil War Reenactment (September 21 and 22 next year.) In the past, they have had more than 500 reenactors participate. Ghost tours are held the last two weekends of every October. In July, Kids’ History Camps and Adult History Camps take place at Zoar and their sister attraction, Fort Laurens.

TOUR HIGHLIGHTS

To tour the village’s historic buildings, start at the Zoar Store and Visitor Center. Built across from the hotel in 1833, it served as the business headquarters for the Society, the post office, and a store. Since the Society’s members had no cash, they were able to purchase items from the store based on labor given to the society. Hired help and farmers in the surrounding territory paid cash. An addition at the rear of the store served as a dairy. In 2018, it is a gift shop, information center, and the place to obtain tickets for self guided or guided tours.

On private guided tours, visitors see four to five buildings in a two-hour time period. The standard ones are usually the Town Hall, the No. 1 House, the Garden House, and The Bakery. Guests can request to see other buildings that fit their interests. For regular, self guided tours, visitors also find the Magazine (storehouse) and Bimeler House and Art Gallery open. The Blacksmith Shop is occasionally open on Fridays and Sundays, but always open on Saturdays during self-guided hours and during special events.

Once the hub of community life, the town hall has served as Zoar’s post office and fire department as well as the Saturday night hall. The Society barbershop was located here, and it was where the Zoar band practiced. It now serves as the local government chambers in the lower level and is the home of two museums. One has many artifacts related to Zoar industries ranging from tools to examples of fabric the women sewed. The other is on the Ohio & Erie canal with model canal boats and canal-related objects. Visitors can also watch a short video on Zoar history.

The No. 1 House was built in 1835. It was intended as a residence for the elderly Society members. However, it became the home for Joseph Bimeler’s family as well as the other two Society trustees and their families. Opened as a museum in 1935, it contains Zoar artifacts ranging from clothing and tools to pottery and more. Its dining room, kitchen, and magazine (for dry good storage) are part of the tour.

Visitors also find lots of signage on topics pertaining to Zoar’s communal history. These cover the canal, agriculture, how the society was formed, industry, and tourism. Look for the excellent time line covering events from the Separatists start in Germany to modern times.

You will want to look for the society’s symbol of the seven-pointed star at the ceiling above the stairs. It was designed by Joseph Bimeler. It represents the inner light of Christ and was worn like a badge of honor to proclaim a person’s adherence to the Separatist creed.

The third museum is the Bimeler Museum and Art Gallery dated 1868. It was once the home of William and Lillian Bimeler. In 2013, a flood lifted the building off of its foundation. It reopened in May 2017 and now houses beautiful artwork in several rooms.

We saw a temporary exhibit of paintings and watercolors depicting the village and its surrounding countryside by artists from the Cleveland School of Art. One room was devoted to August Biehle’s artwork. He visited Zoar for almost 40 years. We also viewed paintings by George Adomeit, Tomas Maier, and Joseph Jicha who interpreted Zoar in a more artistic fashion. This museum has no admission.

The Garden House was the home of Simon Beuter, the Society’s gardener, and his family. There is one greenhouse on the property. Covering an acre of ground, the large Norway spruce tree in the garden’s center depicts everlasting life. It is circled by a hedge of Arbor Vitae. Outside the green path circling the hedge are twelve Irish juniper trees representing the twelve apostles. The paths symbolize the different paths to heaven radiating from the garden’s center.

Another tour spot is The Bakery dated 1845. It was known for its bread, buns, and gingerbread. You can still purchase baked goods today from June through September on Friday and Saturday 11:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. and Sunday from noon to 4:00 p.m.

The Zoar Hotel is one of the spots explored during Zoar Ghost Tours. It had 40 sleeping rooms and a very large dining room. It accommodated everyone from beggars to President William McKinley. Known for its food and lodging, it was a hotel until 1953.

To learn about village buildings such as the church, assembly house, and school, take a virtual tour of their web site. Clicking on each of the buildings provides the historical significance of each structure.

There are four places to eat. Canal Street Diner serves casual food. Canal Tavern of Zoar features fine American and German cuisine in the former 1829 Canawler Inn. Firehouse Grille & Pub, in the #23 house, the former home of the town doctor, has casual American dining. Simply Cinnamon is a local deli and café.

The village also offers bed and breakfasts with historical ties. Keeping Room Bed and Breakfast was the former home of Zoar’s treasurer. It was built in 1877. The Cobbler Shop Bed and Breakfast is housed in an historic home full of antiques dating to 1828. The owners run one of four village antique shops. The 1863 Cider Mill is home to Crafting Retreat. The Zoar School Inn Bed & Breakfast was the schoolhouse in 1836 serving that function until 1868.

DETAILS

It is necessary to purchase a wristband at the Zoar store at 198 Main Street to tour the historic buildings. The phone number is (330) 874-3011. Price is $8 for adults (18+) and $4 for a child (ages 5-17.) Zoar is closed from November through March. During the rest of the year, it is open on Saturdays from 11:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. and on Sundays, noon to 4:00 p.m. During the summer season, June through September, it is also open Wednesday through Friday with the hours the same as Saturday’s.

Combination tickets with Fort Laurens are $10 for adults (18+) and $5 for children (ages 5-17). They are available at either Zoar or Fort Laurens. The two tickets must be used the same day. I recommend going to Fort Laurens first for 1-1/2 hours then spending the rest of the day at Zoar.

Visitors Center at Fort Laurens

Fort Foundation Circling the Tree

Excavations Display Inside the Theater

Model of Fort Laurens Inside the Theater

Some Excavated Items

Crypt of Soldiers Who Died at Fort Laurens

Soldier of the Eighth Pennsylvania

Soldiers at the Fort Member of the Thirteenth Virginia in Navy with Gold

Telegram from President Ford

Tomb of the Unknown Patriot of the Revolutionary War

Zoar Store

Zoar Store Interior

Town Hall

Diana Culler, a Guide at the Town Hall

#1 House, Now a Museum

Joseph Bimeler's Hat and Boots

Items Made in Zoar's Iron Industry

Zoar Emblem Found in the Ceiling of #1 House

Bruce Barth, the Guide at #1 House

Rear of #1 House

Bimeler Museum and Art Gallery

Interior of Bimeler Museum and Art Gallery

Fireplace; First House, c. 1940 by August Biehle

Plowing Near Zoar c. 1936 by George Adomeit

Part of Their Beautiful Garden

Bimeler's Cabin, the Oldest Building at Zoar

The Assembly House - Where The Leaders Met to Plan the Days Activities

The Third Meetinghouse, Now a Evangelical Church

Zoar Schoolhouse

Zoar Hotel

The Canal Tavern

The Cobbler Shop Bed and Breakfast

The Zoar School Inn Bed and Breakfast