Hello Everyone,

After a long trip of more than 4,000 miles, Lewis and Clark finally reached their destination, the Pacific Coast, in 1805. Today travelers can discover the places where these explorers camped and stayed the winter. These include Dismal Nitch, Station Camp, and what is now Cape Discovery State Park in Washington as well as Fort Clatsop and the Salt Works in Oregon.

DISMAL NITCH

In early 1805, the Corps of Discovery was in a desperate state. Their fresh food had run out and their clothes were rotting away. Their goal was to travel as quickly as possible down the Columbia River to meet one of the last trading ships of the season. The plan was to send a set of journals and some collections home as requested by President Jefferson. It also was to provide an opportunity to use an unlimited letter of credit from Jefferson for the goods they needed.

On November 10, the Corps paddled past Grays Point. They spotted the steep, forested shoreline consisting of a series of coves or “nitches” divided from one another by small points of land. They passed Dismal Nitch. As the weather worsened, they sought shelter in a cove upriver.

Rain soaked the group that night and continued at intervals on November 11. On November 12, besides the fierce wind and high waves, they became exposed to thunder, lightning, and hail. Clark described, in his journal that day, the men’s move to Dismal Nitch. He reported for only the second time in the expedition that he feared for his men’s safety.

The rain continued on November 13 and 14. Finally, the storm broke on November 15, allowing the men to move on. Unfortunately, they had missed the trading ship.

For many years, Dismal Nitch had also been the home of many Chinook villages. It included two known summer villages in the vicinity. The Nation was known for its canoe-building prowess and as traders long before the Europeans eyed the region.

The location is 600 feet north/northeast of the eastern end of the present-day Dismal Nitch Safety Rest Area. It’s near the end of the 4.1 mile long Astoria Bridge with a main span that is 1,232 feet long. It’s the longest “continuous truss” bridge in the world. Stop at the parking lot to see great views of the Columbia River, spot an occasional whale, bird watch, or view modern ships gliding by on the river.

STATION CAMP

After the weather improved, the men moved to Station Camp, a Chinook village site called Middle Village, on the west side of Point Ellice. They camped there between November 15 and 25. By the time the Corps reached the site, the Chinooks had moved to their winter camp and the village was unoccupied.

From this site, the men departed to explore the area and have their first view of the Pacific Ocean. Historians called the spot "Station Camp" because the location was Clark's primary survey station for producing a map of the mouth of the Columbia River and the surrounding area. It is regarded as the most detailed and accurate map he made during the entire trip.

It was here that the famous vote was taken which included all Corps members including Sacagawea and Clark’s slave, York. The decision was whether to stay on the north side of the Columbia River (now Washington), move upriver, or move to the south shore of the Columbia River (now Oregon) for the winter before starting their long journey home.

In 2005, archeologists uncovered more than 10,000 artifacts proving the importance of this site as a Chinook trading village. They discovered trade beads, plates, cups, musket balls, arrowheads, Indian fish net weights, and ceremonial items. They found European items dating before and after the Corps of Discovery expedition. Today the park’s site focuses on the Chinook Indian Nation history besides telling the story of the Corps.

CAPE DISAPPOINTMENT STATE PARK

It was at Cape Disappointment that eleven members of the Corps, led by William Clark, succeeded in reaching the Pacific Ocean. Today’s visitors find two lighthouses and the Lewis and Clark Interpretative Center. It also provides 27 miles of ocean beach, hiking trails, and camping. Some of the short hikes follow routes that Clark and the Corps took to explore the beach.

In 1862, Cape Disappointment was armed at the mouth of the Columbia River with smoothbore cannons. The installation became Fort Canby in 1875. Until World War II, the fort continued to be improved. It was turned over to the state in the early 1950s. Gun batteries still exist at the park.

A state of Washington Discover Pass is required for vehicle access to the state park for day use. This can be obtained at the park’s automated pay stations. Cost is $10.

CAPE DISAPPOINTMENT LIGHTHOUSE

The force of the Columbia River created one of the most dangerous bars in the world. It resulted in 234 ships sinking, stranding, or burning near the river’s mouth. It became obvious that a lighthouse was necessary.

When the Cape Disappointment Light was recommended to be built in 1848, it was to be the first of eight constructed on the Pacific Coast. However, constant problems forced delays. Money was not appropriated until 1852. Then on September 8, 1853, the Oriole, which had sailed from Baltimore, waited offshore for eight days for weather conditions to improve. It shipwrecked below the Cape attempting to cross the bar. The 32-man crew was saved. However, the ship and all building supplies for the lighthouse were lost.

After the shipwreck, it took two more years for construction to begin. After the lighthouse was designed and built, another problem occurred. It was found that the first-order Fresnel lens was too large for the tower’s lantern room. This resulted in the tower being dismantled and completely rebuilt wasting another two years.

It took until October 15, 1856 to be lit. By that time, it was the eighth active light on the coast.

In 1871, a double dwelling, located 1,300 feet north of the lighthouse, was built for the keepers. Each side of the duplex had 11 rooms. The principal keeper lived on one side with his assistants residing on the other. That year a new bell house was built as a gun blast from a nearby battery had destroyed the old one.

Unfortunately, this 53-foot, brick lighthouse had major shortcomings. The roar of ocean waves sometimes drowned out its fog bell. That was discontinued in 1881. In addition, the light was not visible to those ships approaching from the north. That problem was solved with the building of the North Head lighthouse, located two miles from Cape Disappointment.

Another mishap occurred during the Civil War when fortifications were added to Cape Disappointment. A 15-inch gun discharged in 1865 with its concussion shattering eleven panes of glass in the lighthouse’s lantern room.

The best-known keeper was Captain J. W. “Joel” Munson who worked there from 1865 to 1877. It was Munson who established a lifesaving station at the Cape in 1871. The Coast Guard continues the lifesaving tradition today with its lifeboat station at the Cape. It averages 400 to 500 search and rescues a year and is host command for the Coast Guard’s National Motor Lifeboat School.

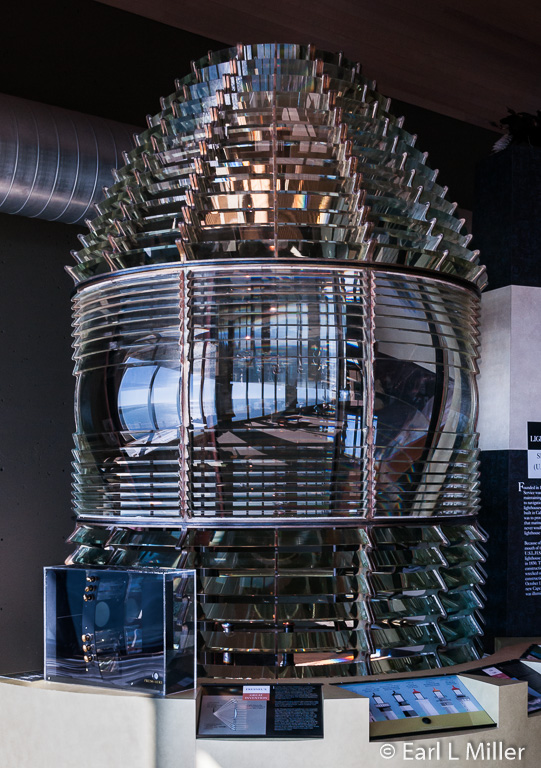

In 1898, a fourth-order lens replaced the first-order lens. The smaller lens had six flash panels, three with ruby shields. It revolved to produce red and white flashes separated by 15 seconds. The first-order lens is now on display at Cape Disappointment’s Lewis and Clark Interpretative Center. The lighthouse’s black band was added in 1930 to distinguish it from North Head Lighthouse.

The lighthouse was electrified in 1937. The Coast Guard wanted to close it in 1956, but didn’t succeed due to the protest of Columbia River pilots. The light, automated in 1973, is still active. Today, the public can explore its grounds. It is the oldest functioning lighthouse on the West Coast. It’s visible from the Lewis and Clark Interpretative Center.

NORTH HEAD LIGHTHOUSE

Located two miles away, the North Head Lighthouse was completed in 1898. It is a 65-foot tower set on a 130-foot cliff directly facing the ocean. Other buildings besides the tower remain on the site. These include two oil houses east of the lighthouse, a keeper’s residence, a duplex for his assistants, a barn, and several outbuildings. This makes it the most intact light station on the Pacific Coast.

North Head’s first-order light had been housed at the Cape Disappointment Light until 1898. In 1937, it was replaced by a fourth-order lens which can now be viewed at the Columbia Maritime Museum in Astoria. Two years later, the lighthouse was electrified. In 1950, two revolving aerobeacons replaced that lens. The last keeper left in July 1961 with the light automated in December of that year. Its signature is a fixed white light.

Known as one of the windiest places in the United States, North Head’s velocities are frequently measured at greater than 100 mph. The U.S. Weather Bureau built a station at North Head between the lighthouse and the keepers’ dwellings in 1902. The station closed in 1955 with the buildings later demolished,

During the first part of the 20th century, the U.S. Army ran a signal station at North Head. The purpose was to communicate weather observations to passing vessels and the batteries at Fort Canby. Personnel residences were located north of the keeper’s dwellings.

When the keepers left, the lighthouse began to fall into disrepair. The Coast Guard restored it in 1984 as well as the keepers’ homes. Washington State Parks took over ownership in October 2012.

North Head Lighthouse is visible from Benson Beach and can also be seen from the first parking lot in the campground. It’s open to the public from 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. daily from May to September 30. Tour admission is $2.50 for adults and free for ages 7-17. Those under age seven are not permitted. Since 2000, the keeper’s duplex and the single-family dwelling are available for overnight stays.

LEWIS AND CLARK INTERPRETATIVE CENTER

The center stands high on the cliffs of Cape Disappointment, 200 feet above the Pacific. You start on the second floor then follow a ramp down to the first floor. What you will see inside are mural-sized timeline panels tracing the Lewis and Clark expedition from St. Louis to the Pacific. As you proceed, you’ll find sketches, paintings, photographs, a few artifacts, and quotes from members of the Corps.

Once downstairs, you will see exhibits focusing particularly on the Corps of Discovery’s Pacific stay. Some displays are interactive. Visitors can try to pack a canoe, follow a treasure hunt, or find animals with a spotting scope. They can also watch the 16-minute movie titled “Of Dreams and Discovery” which covers the Corps trip.

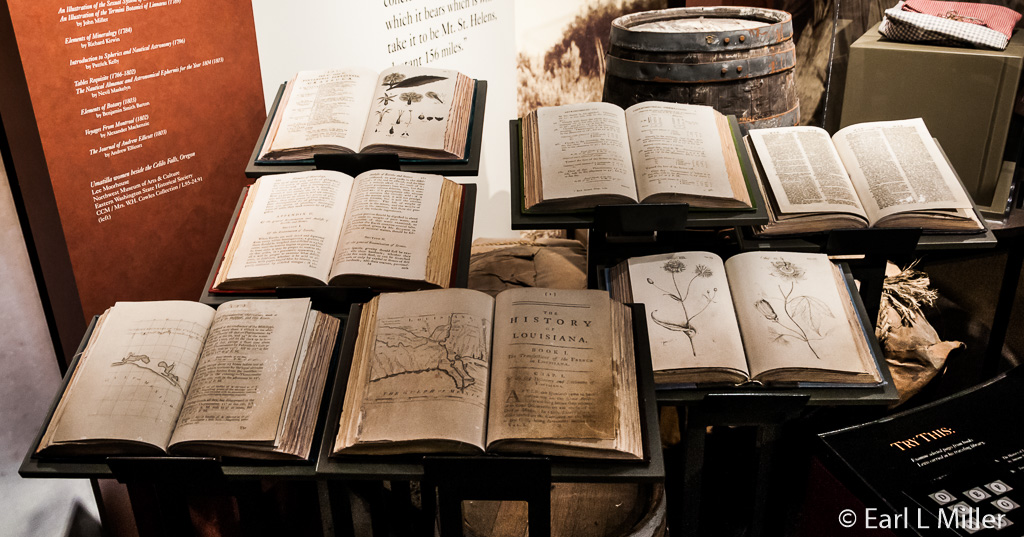

One interesting display was on the seven books that the Corps took with them. They ranged from The Elements of Botany (dated 1803) to Directions for Preserving the Health of Soldiers (dated 1778). A case revealed items the Corps might have used. These included a regiment coat, moccasins, powder horn, leather shoes, sewing kit, and flintlock rifle. Another exhibited the baskets and tools of the Chinooks and explained how they used cedar to build dugouts and homes. One more showed how the mens’ diets changed depending on where they were. It covered their food on the plateau, Bitterroot Mountains, plains, and Colorado River.

I was fascinated by items that had belonged to Patrick Gass, the Corps carpenter. These included the Gass family Bible, a razor box, flask, hatchet, and books. They had been obtained from Gass’s grandson.

A signboard revealed what happened to the Corps members after the expedition. Lewis saw President Jefferson while Clark went to Louisiana. The enlisted men received double pay and 320 acres of land. Lewis and Clark each received double pay and 1600 acres of land. York and Sacagawea received nothing.

On the second floor, you’ll find displays that concentrate on the history of Cape Disappointment after Lewis and Clark. You’ll see exhibits on the two lighthouses including the Fresnel lens and a surfer boat, which I was told is the only one of its kind. Other subjects include the military’s presence including the Coast Guard and the area’s shipwrecks and natural history. The second floor also houses a gift shop and an observation deck with great views of the Pacific and Cape Disappointment Lighthouse.

Hours are April 1 to September 30, 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. daily. From October 1 to March 31, the Center has the same hours but is closed on Mondays and Tuesdays.

While there is handicapped parking nearby, for others it results in a climb from the parking lot. There is supposed to be a shuttle during the summer. In addition to the $10 day use fee, there is an admission charge of $5 per person for ages 18 and older to see this center. It’s $2.50 for ages 7-17. For those ages six and younger, it’s free. I found $20 for two people, which included the parking fee, to be pricey.

FORT CLATSOP

Based on the advice of the Clatsop Indians, the Corps of Discovery decided to move across the Columbia River to what is now near Astoria. Before moving the entire group, Lewis decided to explore the area. He took five men in a scouting party. Clark remained with the other men performing a variety of housekeeping tasks including fixing their clothes from the long journey they had endured.

Finally, Lewis returned and the Corps made the short journey to Lewis’s chosen location. Upon arrival, the men split into three groups. Clark led a party to the Pacific Ocean in search of salt. Lewis divided the others into a hunting party and a group to cut down trees to construct a fort.

It took 3-1/2 weeks to build. On December 23, 1805, the group started moving into the fort. By Christmas night, everyone was inside. It was named Fort Clatsop in honor of the Indians.

The weather was horrible. Of the 106 days spent at the fort, it rained all but twelve. This resulted with the men coming down with a variety of ailments that the captains treated. Clothing rotted and fleas infested the blankets and bedding.

Each day they hunted for meat, killing more than 130 elk, 20 deer, and many small animals, including fowl, over the course of the winter. They later added whales to their diet. From the hides, the men stitched more than 300 pairs of moccasins. They also prepared elk hide clothing for the journey home and made elk candles to serve as light at the fort.

Lewis spent his time making detailed notes on trees, plants, fish and wildlife. He described more than 30 mammals, birds, and plants formerly not described by science. Clark made maps of the area and updated those of the country through which they had traveled.

The Corps traded for dried fish and root vegetables with the Clatsop and Chinook Indians, who made almost daily trips to the fort. The captains often kept journals about the tribes’ appearances, habits, living conditions, lodges, and abilities as hunters and fishermen.

Lewis and Clark maintained a strict military routine. They posted a sentinel nightly. At sundown daily, they cleared the fort of visitors and locked the gates for the night.

The Corps left on March 23 to return to St. Louis. They ran into resistance with the Clatsops who did not want to trade for canoes. The Corps eventually made a deal for one and found it necessary to steal another since they needed at least two boats to travel.

Lewis gave Fort Clatsop to Coboway, chief of the Clatsops. The Clatsops used the fort as a base for security and other purposes. They did strip away part of the wood. By the middle of the 19th century, because of the region’s heavy rainfall, the original Fort Clatsop had rotted away.

Two replicas have been made of the fort which measured 50 square feet. They were built based on Clark’s journal descriptions and floor plan. It is believed that they were constructed close to if, perhaps, not on where the original fort stood. The first, dated 1955, took 18 months to erect. It lasted until a fire in the enlisted men’s quarters destroyed it during the evening of October 3, 2005. A second one was dedicated March 23, 2006 in a celebration with the Clatsops.

Fort Clatsop is now part of Lewis and Clark National Historical Park. From mid June to Labor Day, you can watch living history as rangers, dressed in buckskins, demonstrate such skills as flintlock gun shooting, hide tanning, and candle making. It’s also the location of free lectures and special events throughout the year. Children can become Junior Rangers.

Inside the Visitor Center, which is open year round, watch short films and two long videos titled “A Clatsop Winter Story” and “A Confluence of Time and Courage.” The first is narrated by a Clatsop woman telling of the Corps experience at Fort Clatsop and the Indian relationships with them. It lasts 22 minutes. The second is a 34-minute video relating the expedition’s entire trip.

Exhibits cover a myriad of subjects. They range from why Jefferson called for the expedition to one on fur trapping. You’ll see the specimens that Lewis and Clark found such as the chickadee and the California condor. Among the other topics covered are fishermen and foragers, the type of tools the Corps carried, firearms, diet, the salt makers camp, and Northwest Coastal Indians.

One large map covers walls plotting the trail’s timeline with quotes from the explorers. Another points out where the various Indian nations were located that they encountered.

Take time to admire the life-size bronze statue, “Arrival,” by Stanley Wanlass. It depicts Lewis with his arms spread, his dog Seaman looking on, a Clatsop Indian showing Clark a flounder, and Clark with a quill pen sketching the fish. It was commissioned for the 175th Lewis and Clark anniversary.

Follow the short path to the fort’s replica. You will see two sparsely furnished buildings inside high walls. The one on the left was for the enlisted men while the one on the right had a room for Lewis and Clark; one for Sacagawea, her husband Toussaint Charboneau, and their infant son; and another for the guards. Stop to admire the statue of Sacagawea on the way to the fort.

The hours at the center are daily 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Admission is $3 for adults, children ages 7-17 $1, under age seven free. The center accepts federal passes.

SALT WORKS

A short trip to Seaside, south of Astoria, allows you to visit the location of the Corps salt works. It’s located 15 miles southwest of Fort Clatsop. Clark was indifferent about salt, but the rest preferred it for flavoring of their food as well as the preservation of meat.

On December 28, 1805, the Captains sent a party of five men to make salt. Using five kettles, they worked constantly boiling 1,400 gallons of seawater to produce this product. To do this, they had to find the following: rocks to build a furnace, wood to burn, and ocean water to boil. For their survival, while doing this, they needed to procure fresh water to drink and game animals for food.

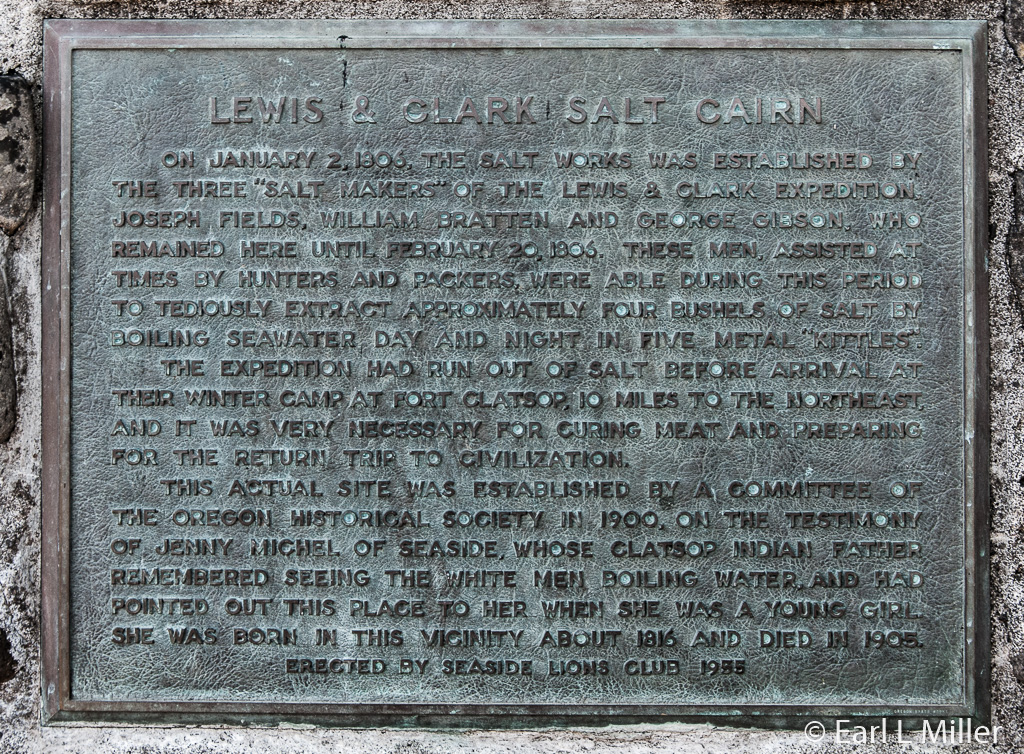

Rocks were in a cairn (oven) shape with one end left open. A fire was placed inside the oven with the five kettles on top. The men prepared approximately four bushels of salt for the return trip home before abandoning the camp on February 20, 1806.

In 1900, the Oregon Historical Society established the site as a memorial to the Corps of Discovery. This was based on the rock pile and the testimony of Jenny Michel, a Clatsop Indian born in 1816. Prior to her death in 1905, she recalled her mother telling her about white men boiling water on that spot. Using sketches from Lewis and Clark’s journals, the Lions Club built a replica of the oven in 1955. The Oregon Historical Society donated the site in 1979 as an addition to Fort Clatsop National Memorial.

During the third weekend of August, costumed reenactors from the Seaside Museum and Historical Society set up camp for 48 hours and make salt around the clock. Children can bring trinkets to “trade” with these modern explorers.

After a long trip of more than 4,000 miles, Lewis and Clark finally reached their destination, the Pacific Coast, in 1805. Today travelers can discover the places where these explorers camped and stayed the winter. These include Dismal Nitch, Station Camp, and what is now Cape Discovery State Park in Washington as well as Fort Clatsop and the Salt Works in Oregon.

DISMAL NITCH

In early 1805, the Corps of Discovery was in a desperate state. Their fresh food had run out and their clothes were rotting away. Their goal was to travel as quickly as possible down the Columbia River to meet one of the last trading ships of the season. The plan was to send a set of journals and some collections home as requested by President Jefferson. It also was to provide an opportunity to use an unlimited letter of credit from Jefferson for the goods they needed.

On November 10, the Corps paddled past Grays Point. They spotted the steep, forested shoreline consisting of a series of coves or “nitches” divided from one another by small points of land. They passed Dismal Nitch. As the weather worsened, they sought shelter in a cove upriver.

Rain soaked the group that night and continued at intervals on November 11. On November 12, besides the fierce wind and high waves, they became exposed to thunder, lightning, and hail. Clark described, in his journal that day, the men’s move to Dismal Nitch. He reported for only the second time in the expedition that he feared for his men’s safety.

The rain continued on November 13 and 14. Finally, the storm broke on November 15, allowing the men to move on. Unfortunately, they had missed the trading ship.

For many years, Dismal Nitch had also been the home of many Chinook villages. It included two known summer villages in the vicinity. The Nation was known for its canoe-building prowess and as traders long before the Europeans eyed the region.

The location is 600 feet north/northeast of the eastern end of the present-day Dismal Nitch Safety Rest Area. It’s near the end of the 4.1 mile long Astoria Bridge with a main span that is 1,232 feet long. It’s the longest “continuous truss” bridge in the world. Stop at the parking lot to see great views of the Columbia River, spot an occasional whale, bird watch, or view modern ships gliding by on the river.

STATION CAMP

After the weather improved, the men moved to Station Camp, a Chinook village site called Middle Village, on the west side of Point Ellice. They camped there between November 15 and 25. By the time the Corps reached the site, the Chinooks had moved to their winter camp and the village was unoccupied.

From this site, the men departed to explore the area and have their first view of the Pacific Ocean. Historians called the spot "Station Camp" because the location was Clark's primary survey station for producing a map of the mouth of the Columbia River and the surrounding area. It is regarded as the most detailed and accurate map he made during the entire trip.

It was here that the famous vote was taken which included all Corps members including Sacagawea and Clark’s slave, York. The decision was whether to stay on the north side of the Columbia River (now Washington), move upriver, or move to the south shore of the Columbia River (now Oregon) for the winter before starting their long journey home.

In 2005, archeologists uncovered more than 10,000 artifacts proving the importance of this site as a Chinook trading village. They discovered trade beads, plates, cups, musket balls, arrowheads, Indian fish net weights, and ceremonial items. They found European items dating before and after the Corps of Discovery expedition. Today the park’s site focuses on the Chinook Indian Nation history besides telling the story of the Corps.

CAPE DISAPPOINTMENT STATE PARK

It was at Cape Disappointment that eleven members of the Corps, led by William Clark, succeeded in reaching the Pacific Ocean. Today’s visitors find two lighthouses and the Lewis and Clark Interpretative Center. It also provides 27 miles of ocean beach, hiking trails, and camping. Some of the short hikes follow routes that Clark and the Corps took to explore the beach.

In 1862, Cape Disappointment was armed at the mouth of the Columbia River with smoothbore cannons. The installation became Fort Canby in 1875. Until World War II, the fort continued to be improved. It was turned over to the state in the early 1950s. Gun batteries still exist at the park.

A state of Washington Discover Pass is required for vehicle access to the state park for day use. This can be obtained at the park’s automated pay stations. Cost is $10.

CAPE DISAPPOINTMENT LIGHTHOUSE

The force of the Columbia River created one of the most dangerous bars in the world. It resulted in 234 ships sinking, stranding, or burning near the river’s mouth. It became obvious that a lighthouse was necessary.

When the Cape Disappointment Light was recommended to be built in 1848, it was to be the first of eight constructed on the Pacific Coast. However, constant problems forced delays. Money was not appropriated until 1852. Then on September 8, 1853, the Oriole, which had sailed from Baltimore, waited offshore for eight days for weather conditions to improve. It shipwrecked below the Cape attempting to cross the bar. The 32-man crew was saved. However, the ship and all building supplies for the lighthouse were lost.

After the shipwreck, it took two more years for construction to begin. After the lighthouse was designed and built, another problem occurred. It was found that the first-order Fresnel lens was too large for the tower’s lantern room. This resulted in the tower being dismantled and completely rebuilt wasting another two years.

It took until October 15, 1856 to be lit. By that time, it was the eighth active light on the coast.

In 1871, a double dwelling, located 1,300 feet north of the lighthouse, was built for the keepers. Each side of the duplex had 11 rooms. The principal keeper lived on one side with his assistants residing on the other. That year a new bell house was built as a gun blast from a nearby battery had destroyed the old one.

Unfortunately, this 53-foot, brick lighthouse had major shortcomings. The roar of ocean waves sometimes drowned out its fog bell. That was discontinued in 1881. In addition, the light was not visible to those ships approaching from the north. That problem was solved with the building of the North Head lighthouse, located two miles from Cape Disappointment.

Another mishap occurred during the Civil War when fortifications were added to Cape Disappointment. A 15-inch gun discharged in 1865 with its concussion shattering eleven panes of glass in the lighthouse’s lantern room.

The best-known keeper was Captain J. W. “Joel” Munson who worked there from 1865 to 1877. It was Munson who established a lifesaving station at the Cape in 1871. The Coast Guard continues the lifesaving tradition today with its lifeboat station at the Cape. It averages 400 to 500 search and rescues a year and is host command for the Coast Guard’s National Motor Lifeboat School.

In 1898, a fourth-order lens replaced the first-order lens. The smaller lens had six flash panels, three with ruby shields. It revolved to produce red and white flashes separated by 15 seconds. The first-order lens is now on display at Cape Disappointment’s Lewis and Clark Interpretative Center. The lighthouse’s black band was added in 1930 to distinguish it from North Head Lighthouse.

The lighthouse was electrified in 1937. The Coast Guard wanted to close it in 1956, but didn’t succeed due to the protest of Columbia River pilots. The light, automated in 1973, is still active. Today, the public can explore its grounds. It is the oldest functioning lighthouse on the West Coast. It’s visible from the Lewis and Clark Interpretative Center.

NORTH HEAD LIGHTHOUSE

Located two miles away, the North Head Lighthouse was completed in 1898. It is a 65-foot tower set on a 130-foot cliff directly facing the ocean. Other buildings besides the tower remain on the site. These include two oil houses east of the lighthouse, a keeper’s residence, a duplex for his assistants, a barn, and several outbuildings. This makes it the most intact light station on the Pacific Coast.

North Head’s first-order light had been housed at the Cape Disappointment Light until 1898. In 1937, it was replaced by a fourth-order lens which can now be viewed at the Columbia Maritime Museum in Astoria. Two years later, the lighthouse was electrified. In 1950, two revolving aerobeacons replaced that lens. The last keeper left in July 1961 with the light automated in December of that year. Its signature is a fixed white light.

Known as one of the windiest places in the United States, North Head’s velocities are frequently measured at greater than 100 mph. The U.S. Weather Bureau built a station at North Head between the lighthouse and the keepers’ dwellings in 1902. The station closed in 1955 with the buildings later demolished,

During the first part of the 20th century, the U.S. Army ran a signal station at North Head. The purpose was to communicate weather observations to passing vessels and the batteries at Fort Canby. Personnel residences were located north of the keeper’s dwellings.

When the keepers left, the lighthouse began to fall into disrepair. The Coast Guard restored it in 1984 as well as the keepers’ homes. Washington State Parks took over ownership in October 2012.

North Head Lighthouse is visible from Benson Beach and can also be seen from the first parking lot in the campground. It’s open to the public from 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. daily from May to September 30. Tour admission is $2.50 for adults and free for ages 7-17. Those under age seven are not permitted. Since 2000, the keeper’s duplex and the single-family dwelling are available for overnight stays.

LEWIS AND CLARK INTERPRETATIVE CENTER

The center stands high on the cliffs of Cape Disappointment, 200 feet above the Pacific. You start on the second floor then follow a ramp down to the first floor. What you will see inside are mural-sized timeline panels tracing the Lewis and Clark expedition from St. Louis to the Pacific. As you proceed, you’ll find sketches, paintings, photographs, a few artifacts, and quotes from members of the Corps.

Once downstairs, you will see exhibits focusing particularly on the Corps of Discovery’s Pacific stay. Some displays are interactive. Visitors can try to pack a canoe, follow a treasure hunt, or find animals with a spotting scope. They can also watch the 16-minute movie titled “Of Dreams and Discovery” which covers the Corps trip.

One interesting display was on the seven books that the Corps took with them. They ranged from The Elements of Botany (dated 1803) to Directions for Preserving the Health of Soldiers (dated 1778). A case revealed items the Corps might have used. These included a regiment coat, moccasins, powder horn, leather shoes, sewing kit, and flintlock rifle. Another exhibited the baskets and tools of the Chinooks and explained how they used cedar to build dugouts and homes. One more showed how the mens’ diets changed depending on where they were. It covered their food on the plateau, Bitterroot Mountains, plains, and Colorado River.

I was fascinated by items that had belonged to Patrick Gass, the Corps carpenter. These included the Gass family Bible, a razor box, flask, hatchet, and books. They had been obtained from Gass’s grandson.

A signboard revealed what happened to the Corps members after the expedition. Lewis saw President Jefferson while Clark went to Louisiana. The enlisted men received double pay and 320 acres of land. Lewis and Clark each received double pay and 1600 acres of land. York and Sacagawea received nothing.

On the second floor, you’ll find displays that concentrate on the history of Cape Disappointment after Lewis and Clark. You’ll see exhibits on the two lighthouses including the Fresnel lens and a surfer boat, which I was told is the only one of its kind. Other subjects include the military’s presence including the Coast Guard and the area’s shipwrecks and natural history. The second floor also houses a gift shop and an observation deck with great views of the Pacific and Cape Disappointment Lighthouse.

Hours are April 1 to September 30, 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. daily. From October 1 to March 31, the Center has the same hours but is closed on Mondays and Tuesdays.

While there is handicapped parking nearby, for others it results in a climb from the parking lot. There is supposed to be a shuttle during the summer. In addition to the $10 day use fee, there is an admission charge of $5 per person for ages 18 and older to see this center. It’s $2.50 for ages 7-17. For those ages six and younger, it’s free. I found $20 for two people, which included the parking fee, to be pricey.

FORT CLATSOP

Based on the advice of the Clatsop Indians, the Corps of Discovery decided to move across the Columbia River to what is now near Astoria. Before moving the entire group, Lewis decided to explore the area. He took five men in a scouting party. Clark remained with the other men performing a variety of housekeeping tasks including fixing their clothes from the long journey they had endured.

Finally, Lewis returned and the Corps made the short journey to Lewis’s chosen location. Upon arrival, the men split into three groups. Clark led a party to the Pacific Ocean in search of salt. Lewis divided the others into a hunting party and a group to cut down trees to construct a fort.

It took 3-1/2 weeks to build. On December 23, 1805, the group started moving into the fort. By Christmas night, everyone was inside. It was named Fort Clatsop in honor of the Indians.

The weather was horrible. Of the 106 days spent at the fort, it rained all but twelve. This resulted with the men coming down with a variety of ailments that the captains treated. Clothing rotted and fleas infested the blankets and bedding.

Each day they hunted for meat, killing more than 130 elk, 20 deer, and many small animals, including fowl, over the course of the winter. They later added whales to their diet. From the hides, the men stitched more than 300 pairs of moccasins. They also prepared elk hide clothing for the journey home and made elk candles to serve as light at the fort.

Lewis spent his time making detailed notes on trees, plants, fish and wildlife. He described more than 30 mammals, birds, and plants formerly not described by science. Clark made maps of the area and updated those of the country through which they had traveled.

The Corps traded for dried fish and root vegetables with the Clatsop and Chinook Indians, who made almost daily trips to the fort. The captains often kept journals about the tribes’ appearances, habits, living conditions, lodges, and abilities as hunters and fishermen.

Lewis and Clark maintained a strict military routine. They posted a sentinel nightly. At sundown daily, they cleared the fort of visitors and locked the gates for the night.

The Corps left on March 23 to return to St. Louis. They ran into resistance with the Clatsops who did not want to trade for canoes. The Corps eventually made a deal for one and found it necessary to steal another since they needed at least two boats to travel.

Lewis gave Fort Clatsop to Coboway, chief of the Clatsops. The Clatsops used the fort as a base for security and other purposes. They did strip away part of the wood. By the middle of the 19th century, because of the region’s heavy rainfall, the original Fort Clatsop had rotted away.

Two replicas have been made of the fort which measured 50 square feet. They were built based on Clark’s journal descriptions and floor plan. It is believed that they were constructed close to if, perhaps, not on where the original fort stood. The first, dated 1955, took 18 months to erect. It lasted until a fire in the enlisted men’s quarters destroyed it during the evening of October 3, 2005. A second one was dedicated March 23, 2006 in a celebration with the Clatsops.

Fort Clatsop is now part of Lewis and Clark National Historical Park. From mid June to Labor Day, you can watch living history as rangers, dressed in buckskins, demonstrate such skills as flintlock gun shooting, hide tanning, and candle making. It’s also the location of free lectures and special events throughout the year. Children can become Junior Rangers.

Inside the Visitor Center, which is open year round, watch short films and two long videos titled “A Clatsop Winter Story” and “A Confluence of Time and Courage.” The first is narrated by a Clatsop woman telling of the Corps experience at Fort Clatsop and the Indian relationships with them. It lasts 22 minutes. The second is a 34-minute video relating the expedition’s entire trip.

Exhibits cover a myriad of subjects. They range from why Jefferson called for the expedition to one on fur trapping. You’ll see the specimens that Lewis and Clark found such as the chickadee and the California condor. Among the other topics covered are fishermen and foragers, the type of tools the Corps carried, firearms, diet, the salt makers camp, and Northwest Coastal Indians.

One large map covers walls plotting the trail’s timeline with quotes from the explorers. Another points out where the various Indian nations were located that they encountered.

Take time to admire the life-size bronze statue, “Arrival,” by Stanley Wanlass. It depicts Lewis with his arms spread, his dog Seaman looking on, a Clatsop Indian showing Clark a flounder, and Clark with a quill pen sketching the fish. It was commissioned for the 175th Lewis and Clark anniversary.

Follow the short path to the fort’s replica. You will see two sparsely furnished buildings inside high walls. The one on the left was for the enlisted men while the one on the right had a room for Lewis and Clark; one for Sacagawea, her husband Toussaint Charboneau, and their infant son; and another for the guards. Stop to admire the statue of Sacagawea on the way to the fort.

The hours at the center are daily 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Admission is $3 for adults, children ages 7-17 $1, under age seven free. The center accepts federal passes.

SALT WORKS

A short trip to Seaside, south of Astoria, allows you to visit the location of the Corps salt works. It’s located 15 miles southwest of Fort Clatsop. Clark was indifferent about salt, but the rest preferred it for flavoring of their food as well as the preservation of meat.

On December 28, 1805, the Captains sent a party of five men to make salt. Using five kettles, they worked constantly boiling 1,400 gallons of seawater to produce this product. To do this, they had to find the following: rocks to build a furnace, wood to burn, and ocean water to boil. For their survival, while doing this, they needed to procure fresh water to drink and game animals for food.

Rocks were in a cairn (oven) shape with one end left open. A fire was placed inside the oven with the five kettles on top. The men prepared approximately four bushels of salt for the return trip home before abandoning the camp on February 20, 1806.

In 1900, the Oregon Historical Society established the site as a memorial to the Corps of Discovery. This was based on the rock pile and the testimony of Jenny Michel, a Clatsop Indian born in 1816. Prior to her death in 1905, she recalled her mother telling her about white men boiling water on that spot. Using sketches from Lewis and Clark’s journals, the Lions Club built a replica of the oven in 1955. The Oregon Historical Society donated the site in 1979 as an addition to Fort Clatsop National Memorial.

During the third weekend of August, costumed reenactors from the Seaside Museum and Historical Society set up camp for 48 hours and make salt around the clock. Children can bring trinkets to “trade” with these modern explorers.

Cape Disappointment Lighthouse

North Head Lighthouse

Lewis and Clark Interpretative Center

Seven Books Taken on Lewis and Clark Expedition

Puget Sound Area Indian Baskets

Cedar Bark Canoe

Fresnel Lens Used in Both Lighthouses

Coast Guard Surfer Boat

Fort Clatsop Visitor Center

Interior of Fort Clatsop Visitor Center

Specimens Lewis and Clark Reported On

"Arrival" by Stanley Wanlass

Statue of Sacagawea and Her Infant Son, Jean Baptiste

Replica of Fort Clatsop

Enlisted Mens' Quarters at Fort Clatsop

Interior of Enlisted Mens' Quarters at Fort Clatsop

Quarters for Guards, Lewis and Clark, and the Charboneau Family

Lewis and Clark Salt Works at Seaside

Sign About Lewis and Clark Salt Works at Seaside