Hello Everyone,

Across the Astoria Bridge and down river to the Pacific Coast, you’ll find Long Beach. This is the location of three unusual attractions: the Kite Museum, the Pacific Coast Cranberry Museum, and Fort Columbia.

My first impression of Long Beach was that you can actually drive on this beach. As we did, we saw super-sized kites in various shapes being flown. I was most impressed with the ones that looked like Tom out of the Tom and Jerry cartoons and the huge circular ones. We could have sat there all day just staring at this scene. However, it was time to discover more at the World Kite Museum.

WORLD KITE MUSEUM

This two-story museum is devoted strictly to kites and kite flying. It’s a one-of-a-kind on this subject.

In its Hall of Fame downstairs, it pays special tribute to outstanding participants in the art, science, religion, and sport of kites from all over the world. Each inductee has a plaque displayed in the Hall of Fame alcove. Miniature kites significant to the individual’s involvement are on display as is information about each person. Induction takes place each August.

We watched a movie downstairs about flying kites on the beach. It included video from the Washington State International Kite Festival that takes place annually in mid August for a week. Competitions, for ages ranging from children to seniors, occur on the beach. There are events for teams as well as individuals. An example isTeam Rokkaku Battle where one team tries to knock another’s kites out of the sky using their own kites. Posters representing each year of the festival line the museum’s walls downstairs.

Upstairs is where you can view kites. We saw the display “A Kite Junket Through Southeast Asia.” Kites from Japan, China, Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia were on display. By observing the different types of kites, you learn that they are made of different materials, have different decorations, and are flown for different reasons.

Japanese kites came from China in the 7th century as part of religious ceremonies to scare evil spirits or to call the gods down the flying line. They became associated with celebrations and holidays. In this section, the museum shows the short video on the Japanese Shironi Festival about the Japanese passion of making and fighting with kites. At this event, 14 teams using 300 kites battle for five days.

Thai kites, dating from the 13th century, were flown from this Buddhist country as a blessing by priests. Stretched across the kites’ backs were reeds which made a humming sound. It’s common today to fly kites in this country at the start of the monsoon. This is done in tournaments where a match occurs between a large kite, the chula, and several smaller kites, pakapaos. The different kites try to pull each other to their own field’s side.

Like the Thai chulas, many Malaysian kites have upper wings. The jewel like decorations on them and their elaborate tails make them different. A more common type is the layang-layang which doesn’t need directions to make. Any square piece of paper and some supple sticks will do.

The first written account of Chinese kites was how they were used in battles to measure distances and to frighten the enemy at night by using noisemakers on them. With the availability of bamboo, paper, and silk, the Han Dynasty allowed kites to become a universal folk art. In modern times, China has been divided into six main kite regions. Each has its own unique style with more than 300 types of kites.

The first Indonesian kites were made from leaves. Their purpose was to get their fishing lines further out to sea. They were also used to catch large fruit bats. The Indonesians created large kites out of native bamboo and cotton fabric. Later on, they used nylon taffeta. They shaped their kites to resemble birds and animals.

We also saw a wall of kites dedicated to India. Under glass, we saw a display of mini kites.

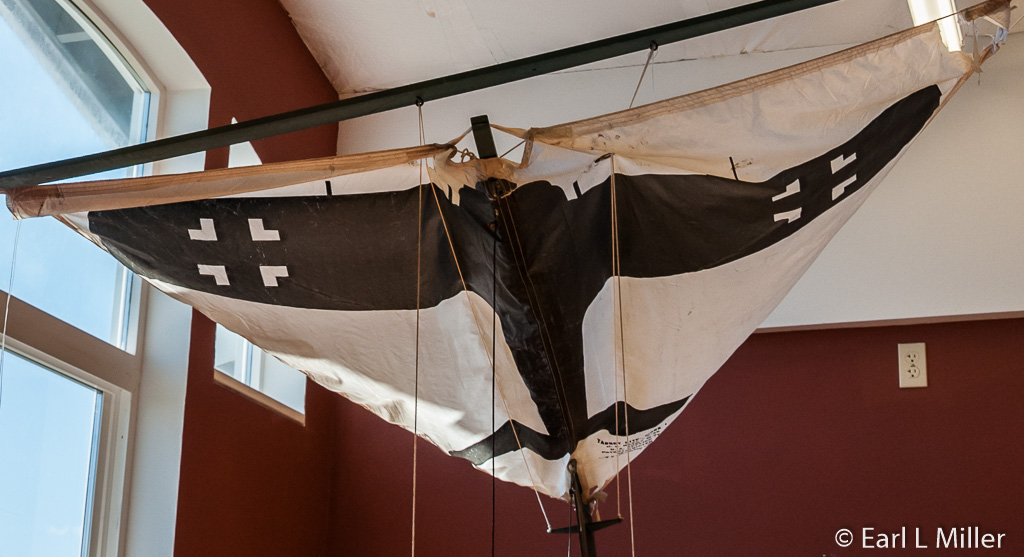

In another room upstairs was the exhibit titled “Kites of World War II.” All of the kites on display were from the 1940's. They included the 13' x 10' barrage kite and two lines’ maneuverable target kites decorated with enemy air planes. World War II uniforms and posters were part of the display.

The Barrage kite was used to protect unarmed merchant vessels carrying cargo across the Atlantic. The wires suspended from the kite were the air equivalent of a minefield. They were capable of shearing off enemy planes’ wings.

One section was on Paul Garber, who invented the target kite. By flying a kite with two lines and a rudder, it could be steered through loops, figure eights, and recoveries. The kite could do acrobatics and dodge bullets as a fighter jet would do.The military used thousands of these kites to train U.S. Army and Navy aircraft gunners. Garber was an emeritus historian for the Smithsonian.

We watched a video on how the military used a kite as a target with an airplane to practice shooting at planes.The kite could be repaired and it allowed the gunner to see the effects of his marksmanship.

Garber also invented a modified three-cell Conyne kite, called the Arctic Mail kite, which was used aboard ships. An airplane flying by, trailing a grapnel, snatched the line of the container, securing it. The containers were used to carry maps, reports, and other documents to and from war headquarters.

The Gibson Girl kite, which received its name due to the “Gibson Girl” shape of its radio transmitter, was also on view. A box kite, aerial wire for the flying line, a hand-cranked generator, and an inflatable raft comprised the small, square package. It was used for sending radio SOS messages.

The museum also supplies material to make a kite. If you don’t know how, staff will be pleased to guide you through the process.

The World Kite Museum is open daily from April through September from 11:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Winter hours are October through March, Friday through Tuesday, from 11:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Admission is adults $5, seniors $4, and children $3. It’s located at 303 Sid Snyder Drive in Long Beach. The telephone number is (360) 642-4020.

PACIFIC COAST CRANBERRY RESEARCH FOUNDATION

While most cranberries in the United States are produced in Massachusetts, they also grow in Wisconsin; New Jersey; Bandon and Seaside, Oregon; and Long Beach Peninsula, Grayland, and Ocean Shores, Washington. Canada, including British Columbia, also grows cranberries. A visit to the Pacific Coast Cranberry Research Foundation in Long Beach provides an excellent overview regarding this berry. You’ll learn its Pacific coast history as well as key phases of its industry from bog preparation and planting to marketing.

Washington State University has conducted research on cranberries on the peninsula since the early 1920's. In 1993, due to funding, the university was forced to close the station. West Coast cranberry growers gathered together to purchase the Station and 40 acres of farmland. WSU continues to support the personnel while the growers farm the bogs.

At the museum, be prepared to read lots of signboards, but you will see some equipment as well. After touring the museum, including its gift shop, head outside to take a walking tour of the farm. This allows for a close-up view of how the crops are planted and cultivated. During October, you can watch the berries being harvested.

ABOUT CRANBERRIES

The first exhibits you’ll see are about the cranberry plant. It’s a low-growing, long-lived evergreen vine that produces runners up to six feet long. The plant starts a 3-6 week flowering period in late May. It reaches maturity 80 days after full bloom. Harvest takes place in late September through early November. Bogs produce in two to four years and can remain productive indefinitely if properly maintained.

There are dozens of cranberry varieties. The original primary variety was the McFarlin. Today most bogs have hybrid species - Stevens, Pilgrim, and Grygleski. The Research Station tests new hybrids for disease resistance, yield, and quality to discover the best to grow in the area.

Commercial cranberries must have well-drained soil. The best are peat, sand, or a four to six-inch layer of sand on top of peat. Sanding takes place throughout the year. It improves the insect and disease control while stimulating upright branch density and rooting.

.

Cranberry production requires access to large amounts of water for irrigation, frost and heat protection, and wet harvesting. Temperature above 85 degrees can damage the plants. The plants are sensitive to frost particularly at bud break and blossom times from March through June. Smudge pots have proved to be the best protection against frost.

Most vines require the ammonium form of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium which they receive via fertilizer. Some peat beds require no nitrogen at all. The plants receive liquid fertilizer through the irrigation system and dry with pellets applied via spreaders.

Pruning is required to stimulate the growth of fruit bearing branches. This process trains the vines to grow in one direction. It can be done with a pruning rake or a motorized pruning machine. Dry harvested bogs are pruned and harvested in one operation while wet harvested bogs are pruned three to four months after harvest.

Weeds, diseases, and insects can all harm the cranberry plants. Today’s growers practice integrated pest management. One harmful insect is the Black-headed worm which is found in all states. It feeds on the cranberry buds and fruit. Several diseases affect the plants resulting in decreases in yield. For example, a variety of fruit rots causes the berries to rot while twig blight kills the fruit buds on uprights.

HARVESTING

Wet harvesting is the method used almost exclusively at Long Beach. First, the bog is flooded with water. Then a mechanized beater moves in a circular pattern around the bog to dislodge the berries from the vines. When the berries float to the water’s surface, they are collected by surrounding them with a floating boom. Paddles or rakes are used as the boom grows tighter to push the berries toward a conveyor. The conveyor lifts the berries into totes on the back of a truck. When the totes are filled, they are hauled to a nearby cannery for processing.

Dry harvesting takes place in the Grayland area. Railway tracks cross these bogs so rail cars can aid in collecting picked berries. They are harvested with specially designed picking machines along straight rows, similar to using a lawnmower. A conveyor lifts the berries to the top of the picker, filling burlap bags hanging from between the handles. Workers on self-propelled rail cars collect the bags and haul them to the sorting shed. As bags are emptied into the sorter, vines and leaves are blown away from the berries. A conveyor then lifts the clean berries into totes for transport to the processing plant.

At the museum, you will see a variety of picking scoops. They also have a suction picker that works like a vacuum cleaner to pick the berries off of the vine. It replaced 10-12 manual laborers. Its disadvantage is that it also collected loose vines and other debris that had to be removed later. In addition, the berries were sometimes damaged due to the suction’s high velocity. One picker on display was invented by Julius Furfurd. It added knives that pruned the vines while picking.

PROCESSING AND MARKETING

West Coast cranberry growers produce 20 percent of the nation’s crop. Approximately 200,000 barrels come from Washington, 500,000 from Oregon, and 850,000 from British Columbia. Ocean Spray, a grower-owned cooperative, is the country’s largest handler of cranberries. It maintains collection facilities at several points including Long Beach. While all points receive berries from growers, only Markham, Washington at Grays Harbor has a processing plant.

All fruit is washed upon arrival at the processing plant and vines and other debris are removed from the berries. Most of the wet harvest crop is stored in 1200-pound capacity tote bins and frozen in large commercial freezers. Much of the rest is cooked and processed as sauce for Thanksgiving and Christmas. Dry harvested berries have a longer shelf life. These are packaged and sold as fresh fruit during the fall holiday season.

Juice and sauce are made from frozen berries throughout the year. They’re thawed in a hot water wash then the juice is extracted by crushing the berries. They are then blended with water, sweetened, pasteurized, and bottled. Cranberry juice is often blended with other juice concentrates.

In a second room, you’ll see experimental harvesting equipment. For dry harvesting, you’ll see strippers and vacuum pickers. While for wet harvesting, the museum displays flailers, manual scoops, nets, and hoses. This is also where you’ll see a large section of cranberry glass which was most popular in the 1950s and 1960s. You’ll also read about the cranberry’s history on the west coast.

A LITTLE HISTORY

Cranberry farming in Southwest Washington dates back to between 1872 and 1877 when four entrepreneurs purchased more than 1600 acres of the peninsula for $1 an acre. One, Anthony Chabot, a Massachusetts visitor, was impressed that the Long Beach Peninsula resembled Cape Cod and that peat soil could be adapted to cranberry cultivation.

The industry built from 1877 until 1900 when it started to stagnate. The East coast filled the markets for the holidays and marketing West Coast berries became expensive due to isolation, high start-up costs for the bogs, and taxes which were frequently higher than profits. Pests brought from the East Coast made farming difficult.

In 1910, syndicates purchased and sold thousands of acres of marshland. However, the increase in farmers and bogs, as well as the problems of the past ten years, made it difficult for the growers who survived. In 1920, J. D. Crowley started research at the Cranberry Research Station. He made recommendations to solve peat, frost, and other problems. Growers did not immediately accept his suggestions, and the Depression did not help matters. The industry was kept alive by a few committed growers.

Cultivation methods over the next 40 years increased product yield and quality. During the 1940's, most growers switched from dry to wet harvesting of the berries.

The industry is strong today with about 235 growers on the West Coast from British Columbia to Oregon. There is a year round demand for cranberry juices, canned goods, and cranberry products. Ninety-nine percent of local growers are part of the Ocean Spray cooperative.

The Pacific Coast Cranberry Museum and Gift Sop is open daily 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. from April through December. Admission is free. It’s located at 2907 Pioneer Road, Long Beach, Washington. The telephone number is (360) 642-5553.

FORT COLUMBIA HISTORICAL STATE PARK

Across the Astoria Bridge on the way to Long Beach, travelers find Fort Columbia Historical State Park. It’s a 593-acre day-use historical park located at the Chinook Point National Historic Landmark on the Columbia River.

It was the home of the Chinook Indians for thousands of years. It was off of this point that Robert Gray anchored and named the river for his ship, Columbia Rediva.

Built between 1896 and 1904, it served as a one of the harbor defenses of the Columbia River until 1947. It was constructed at its location because of the unobstructed view of the Columbia River. At the end of World War II, it was declared surplus and became a state park in 1950.

Today you can still see its 12 wood-frame buildings and four coastal defense batteries including two artillery guns. For recreational use, there are five miles of hiking trails and some unsheltered picnic tables.

An interpretative center focuses on the fort’s history. That is open in July and August from Friday to Sunday from 11:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. To learn more about this park, call Cape Disappointment State Park at (360) 642-3078.

Across the Astoria Bridge and down river to the Pacific Coast, you’ll find Long Beach. This is the location of three unusual attractions: the Kite Museum, the Pacific Coast Cranberry Museum, and Fort Columbia.

My first impression of Long Beach was that you can actually drive on this beach. As we did, we saw super-sized kites in various shapes being flown. I was most impressed with the ones that looked like Tom out of the Tom and Jerry cartoons and the huge circular ones. We could have sat there all day just staring at this scene. However, it was time to discover more at the World Kite Museum.

WORLD KITE MUSEUM

This two-story museum is devoted strictly to kites and kite flying. It’s a one-of-a-kind on this subject.

In its Hall of Fame downstairs, it pays special tribute to outstanding participants in the art, science, religion, and sport of kites from all over the world. Each inductee has a plaque displayed in the Hall of Fame alcove. Miniature kites significant to the individual’s involvement are on display as is information about each person. Induction takes place each August.

We watched a movie downstairs about flying kites on the beach. It included video from the Washington State International Kite Festival that takes place annually in mid August for a week. Competitions, for ages ranging from children to seniors, occur on the beach. There are events for teams as well as individuals. An example isTeam Rokkaku Battle where one team tries to knock another’s kites out of the sky using their own kites. Posters representing each year of the festival line the museum’s walls downstairs.

Upstairs is where you can view kites. We saw the display “A Kite Junket Through Southeast Asia.” Kites from Japan, China, Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia were on display. By observing the different types of kites, you learn that they are made of different materials, have different decorations, and are flown for different reasons.

Japanese kites came from China in the 7th century as part of religious ceremonies to scare evil spirits or to call the gods down the flying line. They became associated with celebrations and holidays. In this section, the museum shows the short video on the Japanese Shironi Festival about the Japanese passion of making and fighting with kites. At this event, 14 teams using 300 kites battle for five days.

Thai kites, dating from the 13th century, were flown from this Buddhist country as a blessing by priests. Stretched across the kites’ backs were reeds which made a humming sound. It’s common today to fly kites in this country at the start of the monsoon. This is done in tournaments where a match occurs between a large kite, the chula, and several smaller kites, pakapaos. The different kites try to pull each other to their own field’s side.

Like the Thai chulas, many Malaysian kites have upper wings. The jewel like decorations on them and their elaborate tails make them different. A more common type is the layang-layang which doesn’t need directions to make. Any square piece of paper and some supple sticks will do.

The first written account of Chinese kites was how they were used in battles to measure distances and to frighten the enemy at night by using noisemakers on them. With the availability of bamboo, paper, and silk, the Han Dynasty allowed kites to become a universal folk art. In modern times, China has been divided into six main kite regions. Each has its own unique style with more than 300 types of kites.

The first Indonesian kites were made from leaves. Their purpose was to get their fishing lines further out to sea. They were also used to catch large fruit bats. The Indonesians created large kites out of native bamboo and cotton fabric. Later on, they used nylon taffeta. They shaped their kites to resemble birds and animals.

We also saw a wall of kites dedicated to India. Under glass, we saw a display of mini kites.

In another room upstairs was the exhibit titled “Kites of World War II.” All of the kites on display were from the 1940's. They included the 13' x 10' barrage kite and two lines’ maneuverable target kites decorated with enemy air planes. World War II uniforms and posters were part of the display.

The Barrage kite was used to protect unarmed merchant vessels carrying cargo across the Atlantic. The wires suspended from the kite were the air equivalent of a minefield. They were capable of shearing off enemy planes’ wings.

One section was on Paul Garber, who invented the target kite. By flying a kite with two lines and a rudder, it could be steered through loops, figure eights, and recoveries. The kite could do acrobatics and dodge bullets as a fighter jet would do.The military used thousands of these kites to train U.S. Army and Navy aircraft gunners. Garber was an emeritus historian for the Smithsonian.

We watched a video on how the military used a kite as a target with an airplane to practice shooting at planes.The kite could be repaired and it allowed the gunner to see the effects of his marksmanship.

Garber also invented a modified three-cell Conyne kite, called the Arctic Mail kite, which was used aboard ships. An airplane flying by, trailing a grapnel, snatched the line of the container, securing it. The containers were used to carry maps, reports, and other documents to and from war headquarters.

The Gibson Girl kite, which received its name due to the “Gibson Girl” shape of its radio transmitter, was also on view. A box kite, aerial wire for the flying line, a hand-cranked generator, and an inflatable raft comprised the small, square package. It was used for sending radio SOS messages.

The museum also supplies material to make a kite. If you don’t know how, staff will be pleased to guide you through the process.

The World Kite Museum is open daily from April through September from 11:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Winter hours are October through March, Friday through Tuesday, from 11:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Admission is adults $5, seniors $4, and children $3. It’s located at 303 Sid Snyder Drive in Long Beach. The telephone number is (360) 642-4020.

PACIFIC COAST CRANBERRY RESEARCH FOUNDATION

While most cranberries in the United States are produced in Massachusetts, they also grow in Wisconsin; New Jersey; Bandon and Seaside, Oregon; and Long Beach Peninsula, Grayland, and Ocean Shores, Washington. Canada, including British Columbia, also grows cranberries. A visit to the Pacific Coast Cranberry Research Foundation in Long Beach provides an excellent overview regarding this berry. You’ll learn its Pacific coast history as well as key phases of its industry from bog preparation and planting to marketing.

Washington State University has conducted research on cranberries on the peninsula since the early 1920's. In 1993, due to funding, the university was forced to close the station. West Coast cranberry growers gathered together to purchase the Station and 40 acres of farmland. WSU continues to support the personnel while the growers farm the bogs.

At the museum, be prepared to read lots of signboards, but you will see some equipment as well. After touring the museum, including its gift shop, head outside to take a walking tour of the farm. This allows for a close-up view of how the crops are planted and cultivated. During October, you can watch the berries being harvested.

ABOUT CRANBERRIES

The first exhibits you’ll see are about the cranberry plant. It’s a low-growing, long-lived evergreen vine that produces runners up to six feet long. The plant starts a 3-6 week flowering period in late May. It reaches maturity 80 days after full bloom. Harvest takes place in late September through early November. Bogs produce in two to four years and can remain productive indefinitely if properly maintained.

There are dozens of cranberry varieties. The original primary variety was the McFarlin. Today most bogs have hybrid species - Stevens, Pilgrim, and Grygleski. The Research Station tests new hybrids for disease resistance, yield, and quality to discover the best to grow in the area.

Commercial cranberries must have well-drained soil. The best are peat, sand, or a four to six-inch layer of sand on top of peat. Sanding takes place throughout the year. It improves the insect and disease control while stimulating upright branch density and rooting.

.

Cranberry production requires access to large amounts of water for irrigation, frost and heat protection, and wet harvesting. Temperature above 85 degrees can damage the plants. The plants are sensitive to frost particularly at bud break and blossom times from March through June. Smudge pots have proved to be the best protection against frost.

Most vines require the ammonium form of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium which they receive via fertilizer. Some peat beds require no nitrogen at all. The plants receive liquid fertilizer through the irrigation system and dry with pellets applied via spreaders.

Pruning is required to stimulate the growth of fruit bearing branches. This process trains the vines to grow in one direction. It can be done with a pruning rake or a motorized pruning machine. Dry harvested bogs are pruned and harvested in one operation while wet harvested bogs are pruned three to four months after harvest.

Weeds, diseases, and insects can all harm the cranberry plants. Today’s growers practice integrated pest management. One harmful insect is the Black-headed worm which is found in all states. It feeds on the cranberry buds and fruit. Several diseases affect the plants resulting in decreases in yield. For example, a variety of fruit rots causes the berries to rot while twig blight kills the fruit buds on uprights.

HARVESTING

Wet harvesting is the method used almost exclusively at Long Beach. First, the bog is flooded with water. Then a mechanized beater moves in a circular pattern around the bog to dislodge the berries from the vines. When the berries float to the water’s surface, they are collected by surrounding them with a floating boom. Paddles or rakes are used as the boom grows tighter to push the berries toward a conveyor. The conveyor lifts the berries into totes on the back of a truck. When the totes are filled, they are hauled to a nearby cannery for processing.

Dry harvesting takes place in the Grayland area. Railway tracks cross these bogs so rail cars can aid in collecting picked berries. They are harvested with specially designed picking machines along straight rows, similar to using a lawnmower. A conveyor lifts the berries to the top of the picker, filling burlap bags hanging from between the handles. Workers on self-propelled rail cars collect the bags and haul them to the sorting shed. As bags are emptied into the sorter, vines and leaves are blown away from the berries. A conveyor then lifts the clean berries into totes for transport to the processing plant.

At the museum, you will see a variety of picking scoops. They also have a suction picker that works like a vacuum cleaner to pick the berries off of the vine. It replaced 10-12 manual laborers. Its disadvantage is that it also collected loose vines and other debris that had to be removed later. In addition, the berries were sometimes damaged due to the suction’s high velocity. One picker on display was invented by Julius Furfurd. It added knives that pruned the vines while picking.

PROCESSING AND MARKETING

West Coast cranberry growers produce 20 percent of the nation’s crop. Approximately 200,000 barrels come from Washington, 500,000 from Oregon, and 850,000 from British Columbia. Ocean Spray, a grower-owned cooperative, is the country’s largest handler of cranberries. It maintains collection facilities at several points including Long Beach. While all points receive berries from growers, only Markham, Washington at Grays Harbor has a processing plant.

All fruit is washed upon arrival at the processing plant and vines and other debris are removed from the berries. Most of the wet harvest crop is stored in 1200-pound capacity tote bins and frozen in large commercial freezers. Much of the rest is cooked and processed as sauce for Thanksgiving and Christmas. Dry harvested berries have a longer shelf life. These are packaged and sold as fresh fruit during the fall holiday season.

Juice and sauce are made from frozen berries throughout the year. They’re thawed in a hot water wash then the juice is extracted by crushing the berries. They are then blended with water, sweetened, pasteurized, and bottled. Cranberry juice is often blended with other juice concentrates.

In a second room, you’ll see experimental harvesting equipment. For dry harvesting, you’ll see strippers and vacuum pickers. While for wet harvesting, the museum displays flailers, manual scoops, nets, and hoses. This is also where you’ll see a large section of cranberry glass which was most popular in the 1950s and 1960s. You’ll also read about the cranberry’s history on the west coast.

A LITTLE HISTORY

Cranberry farming in Southwest Washington dates back to between 1872 and 1877 when four entrepreneurs purchased more than 1600 acres of the peninsula for $1 an acre. One, Anthony Chabot, a Massachusetts visitor, was impressed that the Long Beach Peninsula resembled Cape Cod and that peat soil could be adapted to cranberry cultivation.

The industry built from 1877 until 1900 when it started to stagnate. The East coast filled the markets for the holidays and marketing West Coast berries became expensive due to isolation, high start-up costs for the bogs, and taxes which were frequently higher than profits. Pests brought from the East Coast made farming difficult.

In 1910, syndicates purchased and sold thousands of acres of marshland. However, the increase in farmers and bogs, as well as the problems of the past ten years, made it difficult for the growers who survived. In 1920, J. D. Crowley started research at the Cranberry Research Station. He made recommendations to solve peat, frost, and other problems. Growers did not immediately accept his suggestions, and the Depression did not help matters. The industry was kept alive by a few committed growers.

Cultivation methods over the next 40 years increased product yield and quality. During the 1940's, most growers switched from dry to wet harvesting of the berries.

The industry is strong today with about 235 growers on the West Coast from British Columbia to Oregon. There is a year round demand for cranberry juices, canned goods, and cranberry products. Ninety-nine percent of local growers are part of the Ocean Spray cooperative.

The Pacific Coast Cranberry Museum and Gift Sop is open daily 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. from April through December. Admission is free. It’s located at 2907 Pioneer Road, Long Beach, Washington. The telephone number is (360) 642-5553.

FORT COLUMBIA HISTORICAL STATE PARK

Across the Astoria Bridge on the way to Long Beach, travelers find Fort Columbia Historical State Park. It’s a 593-acre day-use historical park located at the Chinook Point National Historic Landmark on the Columbia River.

It was the home of the Chinook Indians for thousands of years. It was off of this point that Robert Gray anchored and named the river for his ship, Columbia Rediva.

Built between 1896 and 1904, it served as a one of the harbor defenses of the Columbia River until 1947. It was constructed at its location because of the unobstructed view of the Columbia River. At the end of World War II, it was declared surplus and became a state park in 1950.

Today you can still see its 12 wood-frame buildings and four coastal defense batteries including two artillery guns. For recreational use, there are five miles of hiking trails and some unsheltered picnic tables.

An interpretative center focuses on the fort’s history. That is open in July and August from Friday to Sunday from 11:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. To learn more about this park, call Cape Disappointment State Park at (360) 642-3078.

Kite flying at Long Beach

Better View of Circular Kites

Flying Different Types of Kites

Tuxedo Cat Kites

The Kite Museum

Malaysian Kite

Chinese Dragon Kites

Chinese Kite "The Monkey King"

Calcutta Fighting Kites

Earl Showing the Size of the Miniature Kite

Barrage Kite

Target Kite

Arctic Mail Kite

Gibson Girl Kite

Cranberry Museum

Hayden Separator and Screening Equipment

Suction Picker

Cranberry Crusher and Sorter

Cranberry Bog at Pacific Cranberry Research Station

Cranberries in Bog

Fort Columbia

Fort Columbia Battery