Hello Everyone,

Minuteman Missile Historic Site, located in the South Dakota Badlands, portrays the story of the nuclear arms race between the United States and the Soviet Union and the development of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). Established in 1999 under President Bill Clinton, it is the first national park dedicated exclusively to the Cold War.

Its visitor center has informative exhibits. Visitors can purchase a tour of the launch control facility Delta-01, where officers stayed on alert to launch missiles in case of a nuclear attack. The third site, Delta-09, allows a free self-guided tour of a silo containing a Minuteman II training missile. These were all formerly operated by the 66th Strategic Missile Squadron of the 44th Strategic Missile Wing headquartered at Ellsworth Air Force Base in Rapid City, South Dakota.

The facilities are preserved in their historic state with the same equipment and furnishings they had while operational. The missile is the same size and specifications as the one housed in the silo during the Cold War. These are the only components remaining of what once consisted of 150 Minuteman II missiles and 15 launch control centers covering 13,500 square miles.

A LITTLE HISTORY

The United States held a brief nuclear monopoly after detonating the world’s first atomic bomb in 1945. However, in 1949, the Soviets tested their own atomic bomb. To achieve superiority, President Truman announced the development of the hydrogen bomb in 1952 while the Soviet Union tested their own version in 1953.

The challenge became how to deliver these bombs from the safety of their borders. The Soviet Union made headlines in 1957 when they launched Sputnik, a satellite, into space that circled the globe and passed over the United States four times. The question became what time span it would take for the Soviets to fasten a nuclear warhead to one of these missiles used to launch satellites.

President Eisenhower quickly responded by spending an increased amount on American missile development. The United States Air Force established the Air Research and Development Command and approved contracts with defense industry companies to develop ICBMs.

The team developed the Atlas and Titan simultaneously. Although they could deliver payloads of over 5,000 miles away, the problem was finding the right fuel for these missiles. The liquid fuel composition was very volatile and dangerous particularly for onsite crews maintaining the missiles. It had to be stored outside the missiles in separate containers which meant pressurizing empty missiles with nitrogen gas. If the thin Atlas and Titan walls weren’t pressurized or fueled, they would deflate rather than keep their shape. This required constant maintenance as well as refueling before each liftoff. This could take over an hour for the Atlas and 15 minutes for the Titan.

In addition, launch facilities became vulnerable targets due to the proximity of the missiles to each other and the control center. The first Atlas went on alert in 1959 followed by the Titan in 1962. Taking action became necessary when Eisenhower in 1958 received reports that the Soviets would have as many as 500 missiles capable of reaching the United States by 1961.

The nuclear arms race reached an extremely dangerous level during the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962. At that time, missiles had been discovered on that island nation located ninety miles off the Florida coast. Kennedy learned these missiles could be operational within two weeks, reaching targets well within the United States. It was essential that he reach an agreement with Nikita Khrushchev. Inaction might allow enough Soviet buildup to put our country at risk of a nuclear attack. However, an air strike from the U.S. could result in nuclear war.

Kennedy responded by using a naval blockade of all offensive military equipment being shipped to Cuba and by placing 160 intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) on alert. These carried nuclear warheads and could reach the Soviet Union in 30 minutes. The newest was the Minuteman. Although Khruschev first turned down Kennedy’s demands, he later agreed to remove the missiles from Cuba.

The Minuteman was developed with the first one appearing in South Dakota in 1961. It was solid-fueled, rejecting the fuel problems of earlier missiles and could fly further requiring fewer resources. The missiles, with a range of 7,000 miles, could travel over the North Pole and reach a target in the Soviet Union in less than 30 minutes. It’s 1.2 megaton warhead had the explosiveness of more than a million tons of dynamite.

Originally the Air Force wanted 10,000 Minuteman missiles. Kennedy’s Secretary of Defense brought the number down to 1,000 missiles. By 1959, U.S. overflights had proven there was no missile gap, but the U.S. kept moving forward since it maintained the concept of minimal deterrence. The Minuteman could cause destruction near one mile of the intended target.

A rapid growth continued on both sides of an arms race with the United States expanding to a thousand Minuteman ICBMs, located in the Midwest, to absorb a potential nuclear attack on our weapons, sparing the major population centers of the coasts from attack. It took five years and $300 million to build all the facilities. Eventually, 150 missile sites were on alert in western South Dakota with 15 continuously manned launch control facilities.

They were placed in South Dakota for several reasons. One was because Soviet sea-based missiles could not reach these. Another was increased space allowing for fewer casualties. A third was because we could send these missiles over the North Pole. The fourth was because they were close to interstate highways making it easier to move people and materials.

With the key part of the U.S. defense strategy having these missiles as a deterrent, they remained on alert for over 30 years starting in 1963.The Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START) was signed between the United States and Soviets in 1991. Upon orders from President George W. Bush, certain Minuteman missile units started to shut down. In 1994, the last missiles were removed from South Dakota. In 2020, 400 Minuteman missiles remain on alert in Montana, Wyoming, and North Dakota.

VISITOR CENTER

The Center, completed in 2015, has a movie and extensive displays including several interactive ones. It also has videos providing an understanding of this aspect of American history. Visitors learn the story of the Minuteman missiles, nuclear avoidance, the near misses, and the Cold War. They learn how Americans and the Soviets responded to the threat of war.

The lobby contains staff who are eager to answer questions. During the summer season, South Dakota Department of Tourism travel counselors also answer questions about the park and area attractions. Youngsters can participate in a Junior Ranger program. Adults have their National Park Passport stamped and obtain directions to the launch control facility they have reserved.

Earl was impressed by the 30-minute park movie Beneath the Plains: The Minuteman Missile on Alert. It relays information about its system and role as a nuclear deterrent. After viewing the movie, we then spent about two hours exploring the many well-done exhibits.

The following is a summary of the displays. For a full listing, go to Minuteman Missile National Historic Site's web site.

The lobby exhibit The Nation’s Nuclear Defense provides an introduction to the United State’s strategic land, sea, and air defenses and how Ellsworth Air Force Base and the 44th fit within this scheme. Maps provide an overview of the missile field’s geography and command structure. Its 30 Minutes or Less is a multimedia wall of the polarization that occurred between the East and West.

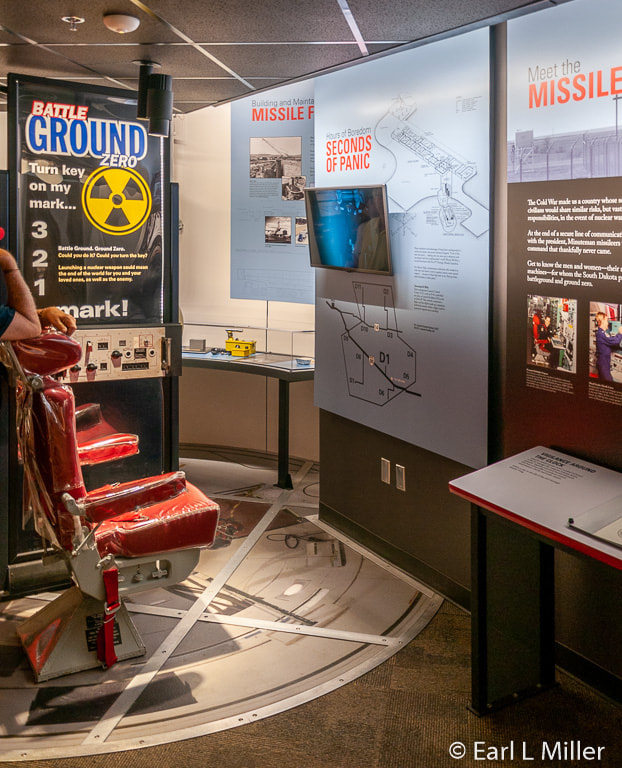

In the section, When the Home Front Becomes the Frontline, learn how the Cold War was a presence in our lives and how it affected our homes and neighborhoods. The Worldwide Delivery in 30 Minutes or Less is a full-size replica of the Delta-01 launch control center blast door complete with Domino’s pizza box art.

Bomb Shelter Basements interprets the popular culture, civil defense strategies, and home front responses during the Cold War. It is done through flipbooks, oral histories, and artifacts. Sit in a recliner taking a moment to peruse primary civil defense documents. Learn about how the civil defense effort involved the interstate and defense highway system. Discover how ranchers and farmers lived with ICBMs in their backyards.

Meet the Missileers explores the lives of the men and women who worked in the launch control centers. You’ll see their photos, memorabilia, uniforms, and snapshots.

Building and Maintaining the Missile Fields connects the Launch Control Facility with the silo that housed the missiles. Look for the circular silo wall with an actual silo cage suspended from the ceiling, a mannequin wearing a missile test uniform, and a graphic of a view into the silo. Exhibits in this section concentrate on the missile technicians. You’ll also learn how missile fields were built and maintained and their imprint on the landscape and rural economy.

We will Bury You looks at the Cold War from the Soviet perspective including their defense and missile systems. See personal photos and read remembrances from Soviet citizens. In this area, you will find a touchable section of the Berlin Wall. Learn about the SS-18 missile which was the Soviet answer to the Minuteman. Look for the slideshow of Soviet Civil Defense posters.

Scale of Destruction/Split Second Decisions interprets the potential destruction of the Nuclear Age and the communication that guided decision making as to whether to launch or not. A push-button LED interactive, Range of Destruction, illustrates the probable damage from 200-kiloton, 500-kiloton, and 1-megaton bombs. Pick up a red phone to listen to the Lines of Communication. It’s an oral history station providing insight into the information and protocol for all military personnel who worked with nuclear weapons. A nearby monitor animates a present-day Minuteman III test launch.

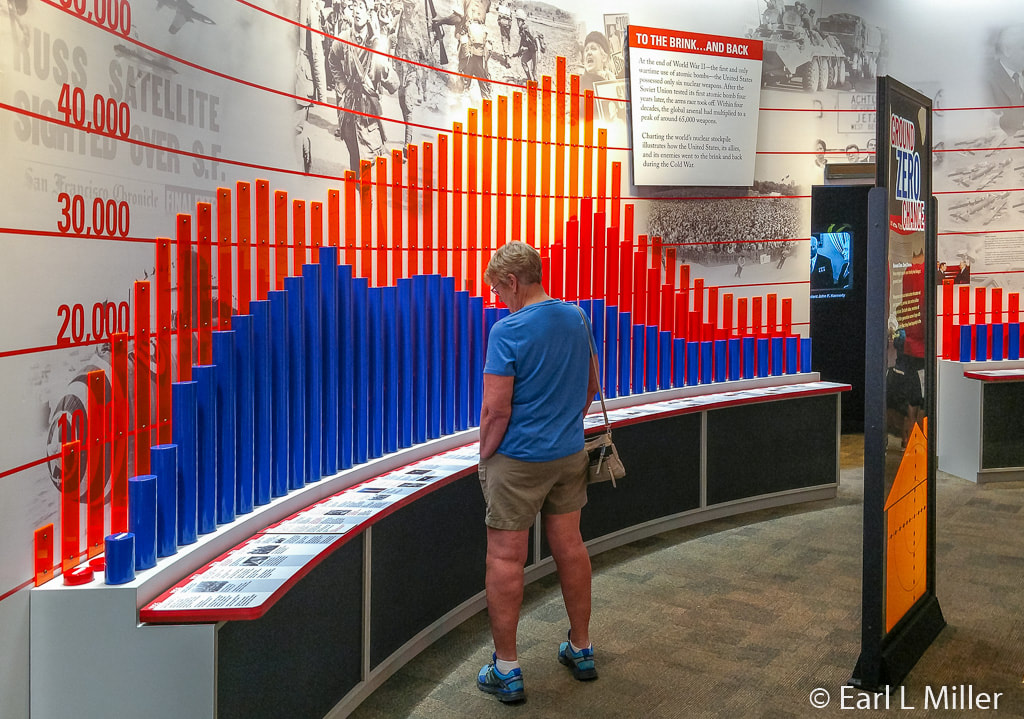

To the Brink and Back contains a backdrop of charts of the growth of the global nuclear stockpile. In 1945, all six warheads were possessed by the United States. They peaked in 1986 to about 65,000 and dwindled in 2009 to about 20,000. The Nuclear Stockpile Sculpture (1945-2010) is a detailed timeline from which to interpret Cold War milestones. This includes wars such as Vietnam and Korea, near misses including six false alarms on both sides, and the journey to arms reduction. View the short film The Big Buildup dramatizing the key moments of nuclear escalation from 1945 through the 1960s. Another details U.S. and Soviet incidents with nuclear weapons through Cold War history.

Build Up/Stand Down looks at the arms reduction with the Minuteman disarming and silo implosions. It speaks about the U.S. and Soviet inspections, the preservation of Delta-01 and Delta-09, and the establishment of the historic site.

Where are We Now, the final display, allows visitors to reflect on what they have seen and enter comments into a journal.

DETAILS

The Visitor Center is located at 1/4 mile north of I-90 exit 131.There is no entrance fee. Winter hours, November 1 through March 31, are as follows: the Center is closed on Sunday and Monday and for five national holidays. From Tuesday through Saturday, the hours are 8:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. During the remainder of the year, the Center is open daily with these same hours. Amenities include restrooms, wi-fi, and a bookstore. The store carries books, educational materials, and interpretative items relating to Minuteman Missile National Historic Site.

DELTA-09

About 15 miles from the visitor center and six miles from the town of Wall, visitors come across a site that looks like it could have been a water well or electric sub station. Instead, this fenced property has a silo that contained a fully operational Minuteman missile with a 1.2 megaton nuclear warhead from 1963 through the early 1990s. It now holds a replica of one of these missiles.

It was one of 150 silos spread across western South Dakota with a total of a thousand deployed nationwide. They were placed in remote locations.

The first Minuteman housed at Delta-09's silo was an IB. It was the second stage in the missile’s development increasing the range of its predecessor, the IA, from 4,300 miles to more than 6,000 miles. The IB, which weighed 65,000 pounds, could travel at speeds in excess of 15,000 mph. Minuteman II’s replaced the IB’s in the early 1970s in Ellsworth’s 44th Missile Wing. They had improved precision and a range of up to 7,500 miles. This meant one could strike effectively almost anywhere on earth. Its capability allowed it to strike within 900 yards of its intended target.

Its 1.2 megaton warhead was the equivalent of 1,200,000 tons of dynamite. It was 66 times stronger than the atomic bomb that devastated Hiroshima, Japan. According to the Minuteman Memorial Historic Site’s web site, “The Minuteman II’s warhead was more powerful than all the bombs the Army Air Force dropped on Europe in their successful bombing campaign that led to American victory in World War II.”

The silo is 12 feet in diameter, 80 feet wide, and made of reinforced concrete with a steel-plate liner. Its door has been welded and fitted with a glass roof. At the site, visitors see such support structures as antennas and a motion sensor.

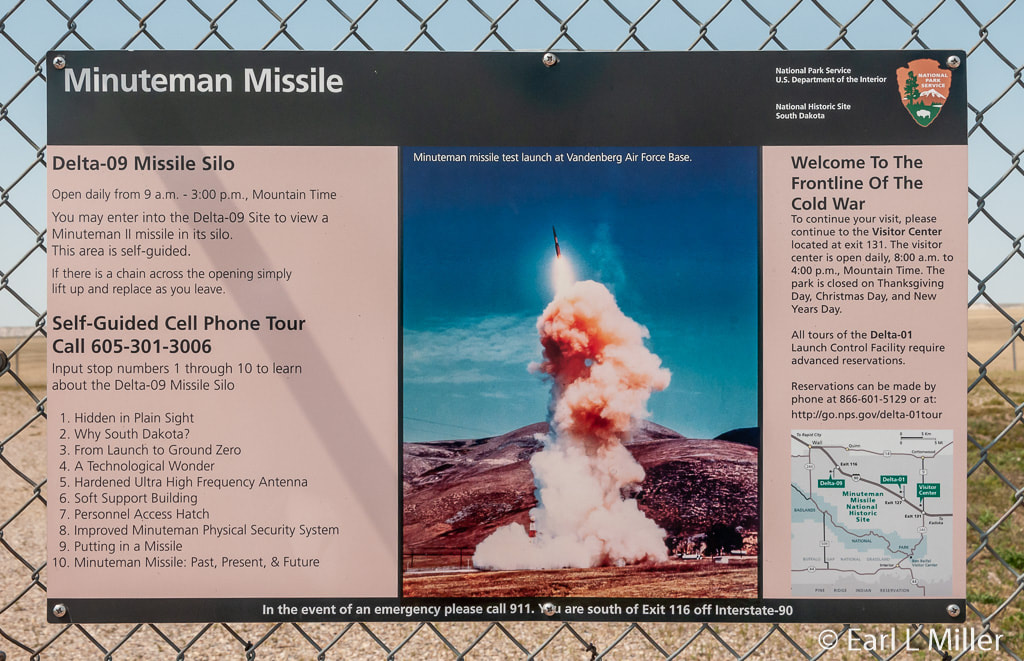

Visitors can take a self-guided cell phone tour of the surface features of the Minuteman Missile silo containing an unarmed missile. By calling, (605) 301-3006, and then selecting numbers one through ten, they’ll learn fascinating historical information about Delta-09. You can do this when you’re not at the site by calling the same phone number.

DETAILS:

It is located on the south side of Exit 116, Interstate 90. There is no entrance fee. It is open daily.

DELTA-01 LAUNCH CONTROL FACILITY

While you can stop at the visitor center and see the missile silo, it is REQUIRED to reserve a tour of the launch control facility up to 90 days in advance. During the summer, tours fill up eight weeks in advance. Reservations can be made on-line or by telephoning (605) 717-7629. Otherwise, you will NOT be able to visit it. The gate to enter D-01 is always kept locked. Guided tours last 45 minutes. They begin and end at the Delta-01 gate and are offered two to five times daily depending upon the season.

Only six people plus the ranger go on the tour at one time. This is because of the 3 foot deep by 5 foot wide elevator taking people to the launch control center and the limited space at the bottom level.

It is stated that people must be able to climb two 15-foot ladders unassisted in case there are elevator problems. These ladders are attached to the wall and very secure. After checking with rangers, I learned that was a very infrequent problem. Children must be at least 4" tall, six years of age, and be able to climb the ladder unassisted.

Rangers also offer an accessible tour that visits the top level and then shows, via a tablet, photos and information about the launch control center downstairs. They do not take the elevator or go to the underground control center. This tour must be reserved at least five days in advance by calling (605) 717-7629. Standard fees apply and the minimum number of participants is two.

On the regular tour, you will first view the topside then take an elevator 31 feet underground to view electronic consoles used by missileers to control ten Minuteman II missiles. You’ll learn how the staff lived and conducted their jobs, what precautions were installed to prevent someone from accidentally launching a missile, and how security was performed.

OUTSIDE

The ranger will first explain to you the variety of communications they used at this launch control center (LCC). They had a high frequency antenna. The ultra high frequency antenna that would communicate with Strategic Air Command aircraft is visible. It looks like a space cone. They also had five ultra low frequency antennas. These viewed the entire earth as an antenna. The Navy used them to communicate with submerged submarines.

Another means of communication was through the hardened intersite cable buried four to eight feet underground. It connected the launch control center to its ten missiles as well as the launch control centers and missiles of the rest of the squadron. It was a distance of over 1,700 miles total length in the Delta flight alone. This meant the missile system could remain secure and fire under any circumstances, even after a nuclear attack. Visitors are able to see and handle a piece of this cable while at Delta-01.

Your guide will point out the Peacekeeper which is a Dodge truck modified by Cadillac Gage with a Cadillac armored body on top. The vehicle would perform random sweeps around the property. It was a very uncomfortable truck which, according to our guide, crews hated. They preferred to take the Dodge regular pickup when the facility manager wasn’t looking.

For recreation, crews would play volleyball, basketball, and horseshoes. Visitors still see the basketball court.

TOPSIDE

The building has been kept as a living museum. The Soviets got to keep one also. However, they lost theirs as it now part of the Ukraine. This U.S. site was still active with missiles on February 21, 1993 and on February 22, 1993, it became a national historic site. The men left everything behind - books, magazines, even garbage in the bedroom garbage cans. If the item was catalogued, since it’s now a national historic site, it can’t be thrown away.

Ten people worked at the LCC. All were based at Ellsworth. Two were missileers who would go through security and then straight down to the control center. They worked 24 hours at a time, 8 times a month. The other eight consisted of a facility manager, a cook, and a 6-person security team. These were on duty for three days then had three days off.

There were seven bedrooms. The facility manager, highest ranking officer, who was in charge of the facility and supervising personnel, had his own. He functioned as the innkeeper. Security personnel had 12 hour shifts with two off duty at a time. They would share their bedrooms. Any repair crews who exceeded 16 hours in a work shift would spend the night at the nearest LCC. The bedroom windows were painted black so the crew could sleep during the day. No one carried any weapons. All arms, such as M-16 and grenade loaders, were locked away.

The cook prepared four meals - breakfast, lunch, dinner, and a midnight snack. In 1985, Ellsworth sent out the first women crews. The cook gave up half of his bedroom so the women could have their own latrine.

Most food was cooked at Ellsworth Air Force Base then frozen and shipped to Delta-01 under guard. It was secured to prevent poisoning and theft so it was locked in the freezer. This site was friends with a nearby farmer who had chickens so the crew always had fresh eggs and omelets. The kitchen is part of the day room with dining at restaurant-style booths.

This is also where men would read books and magazine, play cards, watch television, or lounge on couches. Visitors note the game Battleship and a People magazine from January 1993 when President Bill Clinton was sworn in. All buildings were built the same way so crews decorated them according to their own tastes. Missile crews were never up here. They stayed downstairs.

SECURITY CONTROL CENTER

All missileers came through security. A crew member would use the phone on the fence to relate his codes and verify his credentials to the guard. If the codes didn’t match, that person had to return to Ellsworth which was a 1-1/2 hour drive. If the codes matched, the missileer headed downstairs to hand off to the other team who would then leave.

It was security’s job to make sure the door to the elevator was closed if the blast door to the launch facility was open downstairs. The blast door was only open during crew exchange or when food was picked up.

A motion sensing monitor existed at this facility. If a motion attack occurred, it would turn the lights on downstairs and set off a buzzer. Missileers would call up security who would send two people out in the Peacekeeper. The monitor responded to wind, jackrabbits, birds, bugs, and tumbleweed as well as people who approached the fence. Once, over at the Spearfish launch control facility, two camels from a nearby Passion Play escaped and used the fence as a scratching post. All incidents were immediately checked out.

Missiles ranged from between three to eleven miles away from the launch facility. They were kept at a distance from the launch control center so two facilities would not be hit with a single Soviet rocket.

LAUNCH CONTROL FACILITY

After exploring topside, visitors take an elevator down 31- feet to the actual launch control facility. They’ll arrive downstairs at an area called the atrium where they see the eight-ton blast door that had to be opened from within before an oncoming Missile Combat Crew could enter the launch control center (LCC). Opening it from the outside would take five hours. The door consisted of 3/4 inch steel plate sandwiched with concrete. It was like a bank vault.

Beyond the elevator and the blast door is a “No Lone Zone” which meant no crew member could be here by himself. They had to stay vigilantly in sight of each other. When women arrived in 1985, they did put a curtain in front of the latrine area.

After passing through the blast door, visitors duck through a dim, narrow, four foot tunnel referred to as the “capsule” before reaching the Center. In the console section, one notes that everything is tied down including the mattress and coffee pot. That is because of in case the Center got hit by an incoming rocket, anything not strapped down could become a weapon. The area had heat, air conditioning, and equipment to avoid biological, chemical, and nuclear contamination.

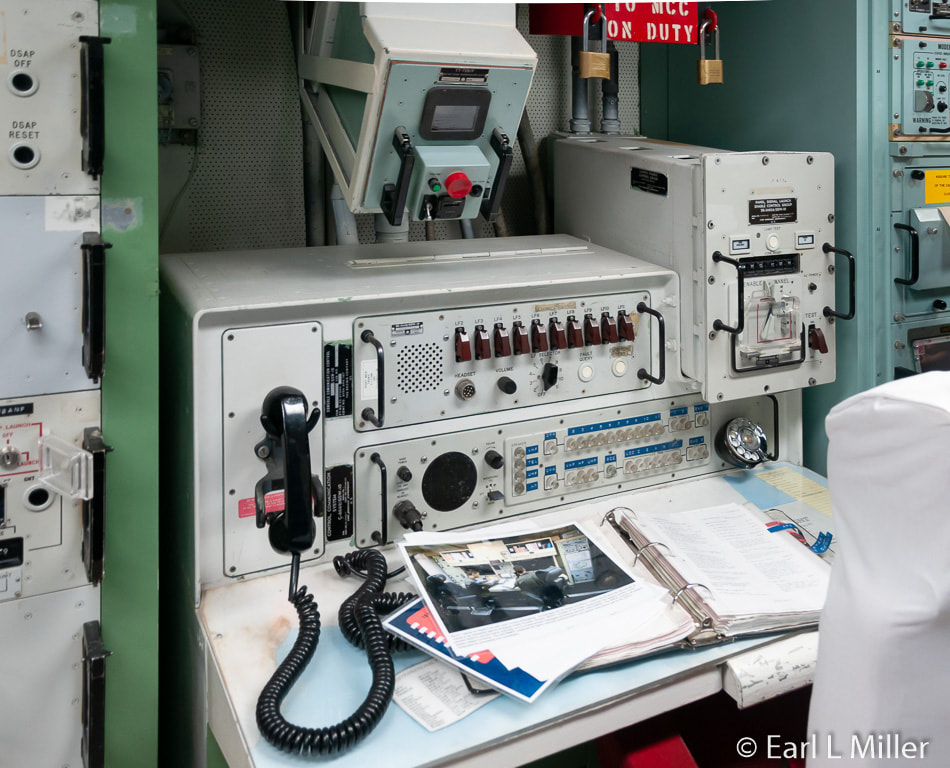

The deputy commander sat in front of a control panel with the necessary communication equipment. The crew commander sat in the capsule’s far end in front of panels displaying the operational and security status of each of ten missile sites. They were responsible for monitoring the equipment and the missile sites, coordinating maintenance and inspections, and performing random Operational Readiness inspections. They also helped the security force upstairs with security. The communication and computer equipment where they worked are on view.

For recreation, they read, watched television, or listened to an AM/FM cassette radio. Some studied for masters’ degrees through a special Air Force educational program. One slept while the other watched the missile systems.

They had a week’s worth of food and water and a week’s worth of air. They had no gas masks, radiation, or chemical suits. The escape hatch for the crew is now closed to the public.

METHOD OF LAUNCHING MISSILE

Only the President of the United States as Commander in Chief of the Armed Services could have given the order to launch a missile in response to enemy attack. A warning would have come from one of two sources: early-warning satellites that detected engine heat of incoming missiles via infrared sensors or ground-based coastal radar capable of detecting submarine-launched missiles. After the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) notified the President, he would have given the command to launch the missiles. The warning orders would have been received on paper via a teletypewriter.

Missileers received the emergency war order with a warble tone coming over speakers in their console. After receiving a coded message giving the command to launch, the missileers would verify the message’s authenticity. From a small, red “Emergency War Order” locked safe, they would remove two launch keys and the launch code. They would then enter the launch code on the enable panel.

Before the keys would activate the launch, confirmation was required from another LCC or from an airborne command center. They would have had a conference call with the other flights. Rotary phones were at the Commander’s and Deputy Commander’s desks.

After the launch was confirmed from another source, they would strap themselves into their two chairs located 12 feet apart. These were harness-equipped aircraft seats fastened to tracks on the floor. The missileers moved along the tracks to the various wall panels and continued to launch. Since the Soviets would have fired first, these officers didn’t want to be knocked out of their chairs before responding with a launch of their own.

The other flight served as backup. They would turn their keys simultaneously verifying a valid launch. Then the two officers at Delta-01 would do a countdown and turn their two keys together. Without this backup, nothing would happen. It took four keys.

The LAUNCH IN PROCESS display on the console would illuminate upon this confirmation. A series of lighted panels existed for each of the ten missiles of Delta flight.

Gas generators would push open the silo’s 80-ton launch doors and the Minuteman would head for its target. As each blasted away, its upper umbilical cord would sever and trigger a MISSILE AWAY light on the commander’s computer control panel. If a launch’s ignition failed, it would also show up on the commander’s console.

DETAILS:

Delta-01 is located on the north side of Exit 127, Interstate 90. The road soon turns to gravel. The LCC is located a half mile on the left.

The cost of the tour is $12 for adults ages 17 and over and $8 for youth ages six to 16. All youth must be accompanied by an adult. To reserve tickets, call (605) 717-7629.

All visitors to Delta-01 can walk up to the large entrance gate and look through the fence into the compound. An exhibit panel provides context to the site. A cell-phone guided tour at the gate is available. By calling, (605) 301-3006, and then selecting numbers 11 through 20, you’ll hear information about this site.

Minuteman Missile Historic Site, located in the South Dakota Badlands, portrays the story of the nuclear arms race between the United States and the Soviet Union and the development of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). Established in 1999 under President Bill Clinton, it is the first national park dedicated exclusively to the Cold War.

Its visitor center has informative exhibits. Visitors can purchase a tour of the launch control facility Delta-01, where officers stayed on alert to launch missiles in case of a nuclear attack. The third site, Delta-09, allows a free self-guided tour of a silo containing a Minuteman II training missile. These were all formerly operated by the 66th Strategic Missile Squadron of the 44th Strategic Missile Wing headquartered at Ellsworth Air Force Base in Rapid City, South Dakota.

The facilities are preserved in their historic state with the same equipment and furnishings they had while operational. The missile is the same size and specifications as the one housed in the silo during the Cold War. These are the only components remaining of what once consisted of 150 Minuteman II missiles and 15 launch control centers covering 13,500 square miles.

A LITTLE HISTORY

The United States held a brief nuclear monopoly after detonating the world’s first atomic bomb in 1945. However, in 1949, the Soviets tested their own atomic bomb. To achieve superiority, President Truman announced the development of the hydrogen bomb in 1952 while the Soviet Union tested their own version in 1953.

The challenge became how to deliver these bombs from the safety of their borders. The Soviet Union made headlines in 1957 when they launched Sputnik, a satellite, into space that circled the globe and passed over the United States four times. The question became what time span it would take for the Soviets to fasten a nuclear warhead to one of these missiles used to launch satellites.

President Eisenhower quickly responded by spending an increased amount on American missile development. The United States Air Force established the Air Research and Development Command and approved contracts with defense industry companies to develop ICBMs.

The team developed the Atlas and Titan simultaneously. Although they could deliver payloads of over 5,000 miles away, the problem was finding the right fuel for these missiles. The liquid fuel composition was very volatile and dangerous particularly for onsite crews maintaining the missiles. It had to be stored outside the missiles in separate containers which meant pressurizing empty missiles with nitrogen gas. If the thin Atlas and Titan walls weren’t pressurized or fueled, they would deflate rather than keep their shape. This required constant maintenance as well as refueling before each liftoff. This could take over an hour for the Atlas and 15 minutes for the Titan.

In addition, launch facilities became vulnerable targets due to the proximity of the missiles to each other and the control center. The first Atlas went on alert in 1959 followed by the Titan in 1962. Taking action became necessary when Eisenhower in 1958 received reports that the Soviets would have as many as 500 missiles capable of reaching the United States by 1961.

The nuclear arms race reached an extremely dangerous level during the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962. At that time, missiles had been discovered on that island nation located ninety miles off the Florida coast. Kennedy learned these missiles could be operational within two weeks, reaching targets well within the United States. It was essential that he reach an agreement with Nikita Khrushchev. Inaction might allow enough Soviet buildup to put our country at risk of a nuclear attack. However, an air strike from the U.S. could result in nuclear war.

Kennedy responded by using a naval blockade of all offensive military equipment being shipped to Cuba and by placing 160 intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) on alert. These carried nuclear warheads and could reach the Soviet Union in 30 minutes. The newest was the Minuteman. Although Khruschev first turned down Kennedy’s demands, he later agreed to remove the missiles from Cuba.

The Minuteman was developed with the first one appearing in South Dakota in 1961. It was solid-fueled, rejecting the fuel problems of earlier missiles and could fly further requiring fewer resources. The missiles, with a range of 7,000 miles, could travel over the North Pole and reach a target in the Soviet Union in less than 30 minutes. It’s 1.2 megaton warhead had the explosiveness of more than a million tons of dynamite.

Originally the Air Force wanted 10,000 Minuteman missiles. Kennedy’s Secretary of Defense brought the number down to 1,000 missiles. By 1959, U.S. overflights had proven there was no missile gap, but the U.S. kept moving forward since it maintained the concept of minimal deterrence. The Minuteman could cause destruction near one mile of the intended target.

A rapid growth continued on both sides of an arms race with the United States expanding to a thousand Minuteman ICBMs, located in the Midwest, to absorb a potential nuclear attack on our weapons, sparing the major population centers of the coasts from attack. It took five years and $300 million to build all the facilities. Eventually, 150 missile sites were on alert in western South Dakota with 15 continuously manned launch control facilities.

They were placed in South Dakota for several reasons. One was because Soviet sea-based missiles could not reach these. Another was increased space allowing for fewer casualties. A third was because we could send these missiles over the North Pole. The fourth was because they were close to interstate highways making it easier to move people and materials.

With the key part of the U.S. defense strategy having these missiles as a deterrent, they remained on alert for over 30 years starting in 1963.The Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START) was signed between the United States and Soviets in 1991. Upon orders from President George W. Bush, certain Minuteman missile units started to shut down. In 1994, the last missiles were removed from South Dakota. In 2020, 400 Minuteman missiles remain on alert in Montana, Wyoming, and North Dakota.

VISITOR CENTER

The Center, completed in 2015, has a movie and extensive displays including several interactive ones. It also has videos providing an understanding of this aspect of American history. Visitors learn the story of the Minuteman missiles, nuclear avoidance, the near misses, and the Cold War. They learn how Americans and the Soviets responded to the threat of war.

The lobby contains staff who are eager to answer questions. During the summer season, South Dakota Department of Tourism travel counselors also answer questions about the park and area attractions. Youngsters can participate in a Junior Ranger program. Adults have their National Park Passport stamped and obtain directions to the launch control facility they have reserved.

Earl was impressed by the 30-minute park movie Beneath the Plains: The Minuteman Missile on Alert. It relays information about its system and role as a nuclear deterrent. After viewing the movie, we then spent about two hours exploring the many well-done exhibits.

The following is a summary of the displays. For a full listing, go to Minuteman Missile National Historic Site's web site.

The lobby exhibit The Nation’s Nuclear Defense provides an introduction to the United State’s strategic land, sea, and air defenses and how Ellsworth Air Force Base and the 44th fit within this scheme. Maps provide an overview of the missile field’s geography and command structure. Its 30 Minutes or Less is a multimedia wall of the polarization that occurred between the East and West.

In the section, When the Home Front Becomes the Frontline, learn how the Cold War was a presence in our lives and how it affected our homes and neighborhoods. The Worldwide Delivery in 30 Minutes or Less is a full-size replica of the Delta-01 launch control center blast door complete with Domino’s pizza box art.

Bomb Shelter Basements interprets the popular culture, civil defense strategies, and home front responses during the Cold War. It is done through flipbooks, oral histories, and artifacts. Sit in a recliner taking a moment to peruse primary civil defense documents. Learn about how the civil defense effort involved the interstate and defense highway system. Discover how ranchers and farmers lived with ICBMs in their backyards.

Meet the Missileers explores the lives of the men and women who worked in the launch control centers. You’ll see their photos, memorabilia, uniforms, and snapshots.

Building and Maintaining the Missile Fields connects the Launch Control Facility with the silo that housed the missiles. Look for the circular silo wall with an actual silo cage suspended from the ceiling, a mannequin wearing a missile test uniform, and a graphic of a view into the silo. Exhibits in this section concentrate on the missile technicians. You’ll also learn how missile fields were built and maintained and their imprint on the landscape and rural economy.

We will Bury You looks at the Cold War from the Soviet perspective including their defense and missile systems. See personal photos and read remembrances from Soviet citizens. In this area, you will find a touchable section of the Berlin Wall. Learn about the SS-18 missile which was the Soviet answer to the Minuteman. Look for the slideshow of Soviet Civil Defense posters.

Scale of Destruction/Split Second Decisions interprets the potential destruction of the Nuclear Age and the communication that guided decision making as to whether to launch or not. A push-button LED interactive, Range of Destruction, illustrates the probable damage from 200-kiloton, 500-kiloton, and 1-megaton bombs. Pick up a red phone to listen to the Lines of Communication. It’s an oral history station providing insight into the information and protocol for all military personnel who worked with nuclear weapons. A nearby monitor animates a present-day Minuteman III test launch.

To the Brink and Back contains a backdrop of charts of the growth of the global nuclear stockpile. In 1945, all six warheads were possessed by the United States. They peaked in 1986 to about 65,000 and dwindled in 2009 to about 20,000. The Nuclear Stockpile Sculpture (1945-2010) is a detailed timeline from which to interpret Cold War milestones. This includes wars such as Vietnam and Korea, near misses including six false alarms on both sides, and the journey to arms reduction. View the short film The Big Buildup dramatizing the key moments of nuclear escalation from 1945 through the 1960s. Another details U.S. and Soviet incidents with nuclear weapons through Cold War history.

Build Up/Stand Down looks at the arms reduction with the Minuteman disarming and silo implosions. It speaks about the U.S. and Soviet inspections, the preservation of Delta-01 and Delta-09, and the establishment of the historic site.

Where are We Now, the final display, allows visitors to reflect on what they have seen and enter comments into a journal.

DETAILS

The Visitor Center is located at 1/4 mile north of I-90 exit 131.There is no entrance fee. Winter hours, November 1 through March 31, are as follows: the Center is closed on Sunday and Monday and for five national holidays. From Tuesday through Saturday, the hours are 8:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. During the remainder of the year, the Center is open daily with these same hours. Amenities include restrooms, wi-fi, and a bookstore. The store carries books, educational materials, and interpretative items relating to Minuteman Missile National Historic Site.

DELTA-09

About 15 miles from the visitor center and six miles from the town of Wall, visitors come across a site that looks like it could have been a water well or electric sub station. Instead, this fenced property has a silo that contained a fully operational Minuteman missile with a 1.2 megaton nuclear warhead from 1963 through the early 1990s. It now holds a replica of one of these missiles.

It was one of 150 silos spread across western South Dakota with a total of a thousand deployed nationwide. They were placed in remote locations.

The first Minuteman housed at Delta-09's silo was an IB. It was the second stage in the missile’s development increasing the range of its predecessor, the IA, from 4,300 miles to more than 6,000 miles. The IB, which weighed 65,000 pounds, could travel at speeds in excess of 15,000 mph. Minuteman II’s replaced the IB’s in the early 1970s in Ellsworth’s 44th Missile Wing. They had improved precision and a range of up to 7,500 miles. This meant one could strike effectively almost anywhere on earth. Its capability allowed it to strike within 900 yards of its intended target.

Its 1.2 megaton warhead was the equivalent of 1,200,000 tons of dynamite. It was 66 times stronger than the atomic bomb that devastated Hiroshima, Japan. According to the Minuteman Memorial Historic Site’s web site, “The Minuteman II’s warhead was more powerful than all the bombs the Army Air Force dropped on Europe in their successful bombing campaign that led to American victory in World War II.”

The silo is 12 feet in diameter, 80 feet wide, and made of reinforced concrete with a steel-plate liner. Its door has been welded and fitted with a glass roof. At the site, visitors see such support structures as antennas and a motion sensor.

Visitors can take a self-guided cell phone tour of the surface features of the Minuteman Missile silo containing an unarmed missile. By calling, (605) 301-3006, and then selecting numbers one through ten, they’ll learn fascinating historical information about Delta-09. You can do this when you’re not at the site by calling the same phone number.

DETAILS:

It is located on the south side of Exit 116, Interstate 90. There is no entrance fee. It is open daily.

DELTA-01 LAUNCH CONTROL FACILITY

While you can stop at the visitor center and see the missile silo, it is REQUIRED to reserve a tour of the launch control facility up to 90 days in advance. During the summer, tours fill up eight weeks in advance. Reservations can be made on-line or by telephoning (605) 717-7629. Otherwise, you will NOT be able to visit it. The gate to enter D-01 is always kept locked. Guided tours last 45 minutes. They begin and end at the Delta-01 gate and are offered two to five times daily depending upon the season.

Only six people plus the ranger go on the tour at one time. This is because of the 3 foot deep by 5 foot wide elevator taking people to the launch control center and the limited space at the bottom level.

It is stated that people must be able to climb two 15-foot ladders unassisted in case there are elevator problems. These ladders are attached to the wall and very secure. After checking with rangers, I learned that was a very infrequent problem. Children must be at least 4" tall, six years of age, and be able to climb the ladder unassisted.

Rangers also offer an accessible tour that visits the top level and then shows, via a tablet, photos and information about the launch control center downstairs. They do not take the elevator or go to the underground control center. This tour must be reserved at least five days in advance by calling (605) 717-7629. Standard fees apply and the minimum number of participants is two.

On the regular tour, you will first view the topside then take an elevator 31 feet underground to view electronic consoles used by missileers to control ten Minuteman II missiles. You’ll learn how the staff lived and conducted their jobs, what precautions were installed to prevent someone from accidentally launching a missile, and how security was performed.

OUTSIDE

The ranger will first explain to you the variety of communications they used at this launch control center (LCC). They had a high frequency antenna. The ultra high frequency antenna that would communicate with Strategic Air Command aircraft is visible. It looks like a space cone. They also had five ultra low frequency antennas. These viewed the entire earth as an antenna. The Navy used them to communicate with submerged submarines.

Another means of communication was through the hardened intersite cable buried four to eight feet underground. It connected the launch control center to its ten missiles as well as the launch control centers and missiles of the rest of the squadron. It was a distance of over 1,700 miles total length in the Delta flight alone. This meant the missile system could remain secure and fire under any circumstances, even after a nuclear attack. Visitors are able to see and handle a piece of this cable while at Delta-01.

Your guide will point out the Peacekeeper which is a Dodge truck modified by Cadillac Gage with a Cadillac armored body on top. The vehicle would perform random sweeps around the property. It was a very uncomfortable truck which, according to our guide, crews hated. They preferred to take the Dodge regular pickup when the facility manager wasn’t looking.

For recreation, crews would play volleyball, basketball, and horseshoes. Visitors still see the basketball court.

TOPSIDE

The building has been kept as a living museum. The Soviets got to keep one also. However, they lost theirs as it now part of the Ukraine. This U.S. site was still active with missiles on February 21, 1993 and on February 22, 1993, it became a national historic site. The men left everything behind - books, magazines, even garbage in the bedroom garbage cans. If the item was catalogued, since it’s now a national historic site, it can’t be thrown away.

Ten people worked at the LCC. All were based at Ellsworth. Two were missileers who would go through security and then straight down to the control center. They worked 24 hours at a time, 8 times a month. The other eight consisted of a facility manager, a cook, and a 6-person security team. These were on duty for three days then had three days off.

There were seven bedrooms. The facility manager, highest ranking officer, who was in charge of the facility and supervising personnel, had his own. He functioned as the innkeeper. Security personnel had 12 hour shifts with two off duty at a time. They would share their bedrooms. Any repair crews who exceeded 16 hours in a work shift would spend the night at the nearest LCC. The bedroom windows were painted black so the crew could sleep during the day. No one carried any weapons. All arms, such as M-16 and grenade loaders, were locked away.

The cook prepared four meals - breakfast, lunch, dinner, and a midnight snack. In 1985, Ellsworth sent out the first women crews. The cook gave up half of his bedroom so the women could have their own latrine.

Most food was cooked at Ellsworth Air Force Base then frozen and shipped to Delta-01 under guard. It was secured to prevent poisoning and theft so it was locked in the freezer. This site was friends with a nearby farmer who had chickens so the crew always had fresh eggs and omelets. The kitchen is part of the day room with dining at restaurant-style booths.

This is also where men would read books and magazine, play cards, watch television, or lounge on couches. Visitors note the game Battleship and a People magazine from January 1993 when President Bill Clinton was sworn in. All buildings were built the same way so crews decorated them according to their own tastes. Missile crews were never up here. They stayed downstairs.

SECURITY CONTROL CENTER

All missileers came through security. A crew member would use the phone on the fence to relate his codes and verify his credentials to the guard. If the codes didn’t match, that person had to return to Ellsworth which was a 1-1/2 hour drive. If the codes matched, the missileer headed downstairs to hand off to the other team who would then leave.

It was security’s job to make sure the door to the elevator was closed if the blast door to the launch facility was open downstairs. The blast door was only open during crew exchange or when food was picked up.

A motion sensing monitor existed at this facility. If a motion attack occurred, it would turn the lights on downstairs and set off a buzzer. Missileers would call up security who would send two people out in the Peacekeeper. The monitor responded to wind, jackrabbits, birds, bugs, and tumbleweed as well as people who approached the fence. Once, over at the Spearfish launch control facility, two camels from a nearby Passion Play escaped and used the fence as a scratching post. All incidents were immediately checked out.

Missiles ranged from between three to eleven miles away from the launch facility. They were kept at a distance from the launch control center so two facilities would not be hit with a single Soviet rocket.

LAUNCH CONTROL FACILITY

After exploring topside, visitors take an elevator down 31- feet to the actual launch control facility. They’ll arrive downstairs at an area called the atrium where they see the eight-ton blast door that had to be opened from within before an oncoming Missile Combat Crew could enter the launch control center (LCC). Opening it from the outside would take five hours. The door consisted of 3/4 inch steel plate sandwiched with concrete. It was like a bank vault.

Beyond the elevator and the blast door is a “No Lone Zone” which meant no crew member could be here by himself. They had to stay vigilantly in sight of each other. When women arrived in 1985, they did put a curtain in front of the latrine area.

After passing through the blast door, visitors duck through a dim, narrow, four foot tunnel referred to as the “capsule” before reaching the Center. In the console section, one notes that everything is tied down including the mattress and coffee pot. That is because of in case the Center got hit by an incoming rocket, anything not strapped down could become a weapon. The area had heat, air conditioning, and equipment to avoid biological, chemical, and nuclear contamination.

The deputy commander sat in front of a control panel with the necessary communication equipment. The crew commander sat in the capsule’s far end in front of panels displaying the operational and security status of each of ten missile sites. They were responsible for monitoring the equipment and the missile sites, coordinating maintenance and inspections, and performing random Operational Readiness inspections. They also helped the security force upstairs with security. The communication and computer equipment where they worked are on view.

For recreation, they read, watched television, or listened to an AM/FM cassette radio. Some studied for masters’ degrees through a special Air Force educational program. One slept while the other watched the missile systems.

They had a week’s worth of food and water and a week’s worth of air. They had no gas masks, radiation, or chemical suits. The escape hatch for the crew is now closed to the public.

METHOD OF LAUNCHING MISSILE

Only the President of the United States as Commander in Chief of the Armed Services could have given the order to launch a missile in response to enemy attack. A warning would have come from one of two sources: early-warning satellites that detected engine heat of incoming missiles via infrared sensors or ground-based coastal radar capable of detecting submarine-launched missiles. After the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) notified the President, he would have given the command to launch the missiles. The warning orders would have been received on paper via a teletypewriter.

Missileers received the emergency war order with a warble tone coming over speakers in their console. After receiving a coded message giving the command to launch, the missileers would verify the message’s authenticity. From a small, red “Emergency War Order” locked safe, they would remove two launch keys and the launch code. They would then enter the launch code on the enable panel.

Before the keys would activate the launch, confirmation was required from another LCC or from an airborne command center. They would have had a conference call with the other flights. Rotary phones were at the Commander’s and Deputy Commander’s desks.

After the launch was confirmed from another source, they would strap themselves into their two chairs located 12 feet apart. These were harness-equipped aircraft seats fastened to tracks on the floor. The missileers moved along the tracks to the various wall panels and continued to launch. Since the Soviets would have fired first, these officers didn’t want to be knocked out of their chairs before responding with a launch of their own.

The other flight served as backup. They would turn their keys simultaneously verifying a valid launch. Then the two officers at Delta-01 would do a countdown and turn their two keys together. Without this backup, nothing would happen. It took four keys.

The LAUNCH IN PROCESS display on the console would illuminate upon this confirmation. A series of lighted panels existed for each of the ten missiles of Delta flight.

Gas generators would push open the silo’s 80-ton launch doors and the Minuteman would head for its target. As each blasted away, its upper umbilical cord would sever and trigger a MISSILE AWAY light on the commander’s computer control panel. If a launch’s ignition failed, it would also show up on the commander’s console.

DETAILS:

Delta-01 is located on the north side of Exit 127, Interstate 90. The road soon turns to gravel. The LCC is located a half mile on the left.

The cost of the tour is $12 for adults ages 17 and over and $8 for youth ages six to 16. All youth must be accompanied by an adult. To reserve tickets, call (605) 717-7629.

All visitors to Delta-01 can walk up to the large entrance gate and look through the fence into the compound. An exhibit panel provides context to the site. A cell-phone guided tour at the gate is available. By calling, (605) 301-3006, and then selecting numbers 11 through 20, you’ll hear information about this site.

Approaching the Visitor Center of Minuteman Missile National Historic Site

Security Sign at the Visitor Center That Would Have Been at the Missile Launch Control Center

Some of the Cold War Exhibits at Minuteman Missile Historic Site Visitor Center

Building and Maintaining the Missile Fields

Sign at Delta-09 Giving Instructions for a Self Guided Tour

Approaching the Delta-09 Missile Silo

Close Up View of Delta-09 Missile Silo

Looking at the Replica of a Minuteman Missile

Waiting to Tour Delta-01, the Launch Control Center - Shows the Communication Antennas

View of the Living Quarters and Garage of Delta-01

Facility Manager's Bedroom and Office

One of Delta-01's Bedrooms

Dining Area at Delta-01

Recreation Area at Delta-01

Security Area

Elevator Between Topside and the Below Ground Launch Control Facility

Blast Door and the "Capsule"

Domino Sign on the Other Side of the Blast Door

Overall View of the Launch Control Facility

Our Guide Al Pointing Out the "Emergency War Order" Locked Safe

Nan Listening to Our Guide Explain the Launch Control Facility

Console for the Deputy Commander

Where the Crew Commander Sat