Hello Everyone,

Those seeking to tour or photograph lighthouses will find a wealth of them on Oregon’s Coast. Between Bandon and Newport, we found several worth exploring. All provide tours and are on the National Register of Historic Places.

COQUILLE RIVER LIGHTHOUSE

Opposite Bandon, on the Coquille River’s north jetty, visitors find Coquille River Lighthouse with its unique architecture. Its a cylindrical tower attached to the east side of an elongated octagonal room. It had a large trumpet protruding from its western wall. The tower is 47 feet in height from its base, the smallest lighthouse on the Oregon coast.

When the station was completed, a long wooden walkway connected it to the keepers’ duplex located 650 feet away. A barn was situated 150 feet beyond the dwelling.

The need for this lighthouse was discovered in the mid 1800's when many vessels bypassed the area because of the rocks and shifting sands at the river’s entrance. At times, with only three feet of water over the bar, the situation proved so discouraging to captains that they kept their ships away. Maritime traffic was important since Bandon was a hub for shipping between San Francisco and Portland. The primary cargo, besides passengers, was fish and timber.

Since Bandon’s citizens wanted more maritime shipping than an occasional vessel, they lobbied to have the area improved. In 1887, Congress built a jetty on the bar’s south side creating a channel 10 to 12 feet at a high tide. Unfortunately, shoaling continued to cause problems. By 1888, it was evident that a jetty on the northern side of the river entrance and a lighthouse were essential for maritime safety.

In 1891, Congress authorized funds for the construction which started in 1895. On February 29, 1896, the lamp in the fourth-order Fresnel lens was lit for the first time. The fixed white light shone for 28 seconds with an eclipse of two seconds. It was seen for 13 miles. During the snowstorm on March 1, the fog signal was first fired up. However, sometimes due to certain weather conditions, it would fail at sea so it was replaced by a more reliable fog siren in 1910.

Two shipwrecks occurred near this lighthouse. On January 9, 1897, the schooner Moro was stuck on the bar. Even though her cargo of lumber, broom handles, and fish was tossed overboard, the ship could not be freed and became a total loss. The schooner Advance in 1905 rammed the north jetty, completed that year, but the ship was able to be saved.

Having Bandon on the river’s opposite shore eliminated the isolation felt at other Oregon coast lighthouses. The station boat was used to secure supplies and ferry the children to school. A boathouse was built in 1901 to shelter it.

By 1915, the Bureau of Lighthouses proposed moving the light and fog signal to the river’s south side. This met with resistance since ships were used to the lighthouse’s position. The move never occurred.

In September 1936, a massive fire nearly destroyed Bandon. It wiped out all but 16 of the town’s 500 buildings. The lighthouse’s keepers, who were the Langlois and Walters families, provided food and shelter for the homeless. They were the last keepers to serve since in 1939, the Coast Guard decided the lighthouse was no longer needed. It was replaced with an automated beacon at the end of the south jetty with a range of 14 miles. Today, it is still 28 seconds on and two seconds off.

The lighthouse stood abandoned for 24 years until Bullards Beach State Park was created in 1964. The lighthouse grounds were included in the park which assumed responsibility for the lighthouse. In 1976, work started to repair the lighthouse which had fallen into disrepair. Oregon State Parks and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers shared the costs and completed the renovation in 1979 when it reopened to the public. The keepers’ quarters and other outbuildings had deteriorated past the point of repair so they were removed. As part of Bandon's centennial celebration in 1991, a new solar powered light was installed in the tower. More restoration was done in 2007.

Today’s visitors can tour the lighthouse’s boiler room where they can view interpretative signs. It is open mid May through September from 11:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.

The park provides three loops of campsites, 13 yurts, and a horse camp. Boat launch facilities are used during the summer and fall seasons. A path leads along open, grassy fields and lowland forest across a plain to sand dunes. All along the path are views of the Coquille River. There are also 4.5 miles of open beach to explore.

The phone number is (541) 347-2209. The entrance to Bullards Beach State Park is on the west side of Highway 101, just north of the Coquille River Bridge. Park signs lead the way to the lighthouse.

UMPQUA RIVER LIGHTHOUSE

In 1849, the Coast Survey determined that the Umpqua River Lighthouse, located on Winchester Bay south of Reedsport, was to be among the first sixteen sites selected for West Coast lighthouses. An initial appropriation was made by Congress in 1851.

When materials arrived by ship from San Francisco in 1855, construction finally began. Because of the region’s stormy weather and problems with the local Indians, construction went slowly. It was finally finished October 10, 1857 when the third-order Fresnel lens lamp was lit. It was the first lighthouse along the Oregon coast.

The lighthouse design consisted of a Cape Cod duplex with keepers quarters on each side of the 92-foot tower from the center of the gabled roof. It was similar to other lighthouse structures that had been built at Cape Flattery and on Dungeness Spit.

The lighthouse suffered from frequent river flooding. In 1861, a gale with record mountain runoff blasted the light’s foundation. With its footings compromised, the house and tower developed a slight tilt. Another major storm in October 1883 made the situation precarious. The keepers petitioned for the lighthouse to be abandoned. In late 1884, the permission was granted. A week later the lens was removed. While workers were dismantling the iron lantern room, the tower began to shake then fell.

In 1888, Congress appropriated funds for a new lighthouse at Umpqua River as well as one at Heceta Head. The purpose was to fill in the gap between those at Cape Arago and Yaquina Head so mariners would enter the visible range of a light as they passed from another. The new light was built above the river on a 100-foot high ridge which overlooked the sand dunes on the river’s south side.

The metalwork was completed in March 21, 1892 and the tower on August 30, 1892. In February 1892, the contractor for the dwellings went bankrupt. Their bondsmen were held responsible for the difference between the original contract and the new bid. The head keeper’s double dwelling was finally finished on January 14, 1893.

In January 1893, when the illuminating apparatus and lens were to be installed, the lens’ base was found to be 15 inches short and another $200 would be needed. Funds were finally obtained in August 1894 with the new first-order Fresnel lens turned on December 31. The new tower stood 65 feet tall and had a focal point of 165 feet above sea level.

Red panels mounted on the lens created a light that flashed white twice, then once red, every 15 seconds. Every 70 minutes the keepers would have to wind up the weight that revolved the lens. Except for a brief outage caused by a 1958 fire, and the period between November 1983 and January 1985, when the lens’ mechanism failed and was repaired, the light’s red and white beam has continued to shine. It is currently on 24 hours a day.

In 1934, a generator building was built near the lighthouse, and the station was electrified. All of the buildings, except for the lighthouse, were eventually torn down.

The Douglas County Parks Department took ownership of the lighthouse and grounds in early 2010. In April 2012, the U.S. Coast Guard also gave Douglas County control of the operation and maintenance of Umpqua Lighthouse and its Fresnel lens.

The lighthouse’s location is near Umpqua Lighthouse State Park, about six miles south of Reedsport and one mile west of Highway 101. The park is open daily.

Visitors find a museum housing exhibits on Oregon’s lighthouses and the 1940-60s Coast Guard, as well as a gift shop, in a historic Coast Guard building located about 200 yards from the lighthouse. From here, volunteer docents lead lighthouse tower and grounds tours. These are available daily from May 1 to October 30 from 10:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. The phone number is (541) 271-4631. The museum is free but there is a charge for the tours.

Outside, overlooking the Pacific Ocean, check out the signage on whale watching. Whales have mostly commonly been seen here in May to June and November to December.

HECETA HEAD LIGHTHOUSE

Heceta Head Lighthouse is located at Heceta Head Lighthouse State Scenic Viewpoint on Highway 101 near milepost 178. It’s about 13 miles north of Florence and 13 miles south of Yachats. Its 56-foot tower is situated 205 feet above the ocean. Not only can you tour this lighthouse, but you can stay at the former assistant keepers’ dwelling which is now a bed and breakfast.

In 1889, Congress appropriated $80,000 for the site purchase and construction. Its purpose was to fill an unlit gap between Yaquina Head’s light and one to be built on Umpqua River. By January 1893, work was completed on two oil houses, a barn, and two Queen Anne-style dwellings. One was a home for the head keeper while his two assistants shared a duplex.

Due to a landslide at the tower site requiring additional excavation, the tower was not finished until the following August. The lamps for the first-order Fresnel lens were finally lit March 30, 1894. The light, 205 feet above the sea, flashed white for ten seconds every minute and was visible for 21 miles. It was and still is rated as the strongest light on the Oregon coast.

Reaching Heceta Head was an arduous task. The wagon road to Florence was impassable much of the year and ships could anchor near the lighthouse only in calm seas. Its remoteness led to keepers and their families hunting, fishing, and raising crops to provide for their own food. If keepers needed supplies, a neighbor hitched his Clydesdale team to a wagon for the two-day round trip. The teacher at the nearby one room schoolhouse taught all eight grades to 14 children, nine of which were keepers’ children.

When keeper Clifford Hermann arrived in 1925, the only unfinished part of the Oregon Coast Highway was between Yachats and Florence. The two towns were connected by a narrow and muddy road used mostly by mail carriers who rode horseback. Between 1930 and 1932, crews built the highway connecting the entire area.

Electricity arrived at the lighthouse station in 1934. An electric motor turned the lens while a light bulb replaced the lamp. When the second assistant’s position was eliminated, the Hermanns moved into the duplex and the single dwelling was torn down.

During World War II, the Coast Guard assigned large numbers of personnel to coastal lighthouse stations. At Heceta Head, 75 men moved into barracks and ate at a mess hall where the single dwelling had stood. They patrolled, with a dozen dogs at their sides, the beaches from Florence to Yachats. Above the lighthouse, they built a lookout tower.

On July 20, 1963, the lighthouse became automated. After that date, personnel from Oregon State Parks and the U.S. Forest Service rented the dwelling. The Forest Service eventually acquired all of the property except for the two acres retained by the Coast Guard where the lighthouse and oil houses stood. The dwelling fell into disrepair when the Forest Service failed to have the funds to maintain it.

In 1970, Lane Community College leased the home for use as classrooms. The College hired caretakers and agreed to do interior repairs in lieu of paying rent. None of the caretakers stayed long until Harry and Anne Tammen arrived in 1973. Under their watch, major changes occurred over four years to return the exterior to its appearance when the first lighthouse keepers moved there. In 1978, the home was listed on the National Historic Register.

Lane College used the assistant lighthouse keepers’ dwelling as classrooms until 1995. That year, the U.S. Forest Service made it into a self-sustaining bed and breakfast. The first floor houses an interpretative center. Tours are given Memorial Day through Labor Day, Thursday through Monday, from 11:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. The phone number is 866-547-3696.

Lighthouse tours are provided daily Memorial Day through Labor Day from 11:00 to 3:00 p.m. In the winter, the hours are 11:00 a.m. to 2:00 p.m. if the weather and staff permit. For information about these tours, call (866) 547-3416

Since 1994, the Oregon Parks Department has owned the lighthouse tower. They did a massive restoration project on it between 2011 and 2013 to return it as it would have appeared in 1894. It now operates as a Private Aid to Navigation. Daily from June through September, from noon to 3:00 on the hour, park volunteers and docents run tours of the outdoor area around the lighthouse and the tower’s ground floor.

The lighthouse, overlooking a beautiful sandy beach, can be reached via a steep half mile trail which begins at the parking area and goes past the bed and breakfast. The Viewpoint also offers caves and tide pools to explore. As part of the Oregon Islands National Wildlife Refuge, it’s home for nesting seabirds, seals, and sea lions. During the spring and early summer, you may also spot migrating whales.

The Viewpoint is a day use area with a parking fee of $5 unless you have an Oregon Parks permit. Note that from the parking lot, the view of the lighthouse is obscured. Drive south to the next overlook and park for a very good view of the lighthouse which allows for photography. We spotted sea lions at this location. A road off Highway 101 leads to the bed and breakfast.

YAQUINA BAY LIGHTHOUSE

The 1871 Yaquina Bay Lighthouse, located at Yaquina Bay State Park, is the oldest structure in Newport. It’s the second-oldest standing lighthouse on the Oregon Coast, the only existing Oregon lighthouse with attached living quarters, and the only historic wood frame Oregon lighthouse still standing. Its beacon, produced by an oil lamp within a fifth order Fresnel lens, shone for only three years, 1871-1874.

In 1870, Congress authorized funding for a lighthouse on Yaquina Bay. The action was taken despite the advice of Colonel R. S. Stockton, Lighthouse Service district engineer. He advocated that a first-order light should be built at Yaquina Head instead of a harbor light on the bay. His advice was ignored, and by the end of October 1871, the new station was finished.

It was a two-story building that included a basement. Chimneys stood near each end of the gabled roof. A three-story tower rose from the building’s rear housing a small, fifth-order Fresnel lens. On November 3, 1871, Charles Peirce, the station’s only keeper, lit the whale oil lamp in the fixed lens. It had a visibility of 12 miles from shore.

The Lighthouse Board reconsidered Stockton’s advice even before the lamp was lit. It decided to construct a new lighthouse on Yaquina Head. In August 1873, a first-order light went into operation there. The new light had a range of 22 miles. The Yaquina Bay light was ordered discontinued and was lit for the last time on October 1, 1874.

Yaquina Bay remained empty for 14 years and fell into disrepair. The station was offered for sale in 1877, but the price offered was too low and the bid was withdrawn. A year later, the roof and outside sheathing were removed to prevent the building from falling apart.

There was talk of reactivating the lighthouse when the railroad arrived at the bay, but this never happened. Instead, small unmanned lanterns were added to assist night bar crossings, and the old lighthouse was officially listed as a “day beacon.”

Several different tenants used the station. From 1888 to 1896, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers used it as a home for John Polhemus, the engineer in charge of the construction of the river’s jetties. From 1906 to 1915, the U.S. Lifesaving Service used the lighthouse as quarters and as lookout. During this period, they built the eight-story steel observation tower that still stands next to the original lighthouse. In 1933, they abandoned the light.

In 1934, the State of Oregon acquired the lighthouse and its surrounding property for public highway, park, and picnic purposes. The Division decided in 1946 the building should be demolished since they were unwilling to make repairs. This led to the formation in 1948 of the Lincoln County Historical Society to save the lighthouse. With the help of the Oregon Historical Society, they were successful. By 1955, the plans for demolition were abandoned.

In 1956, a ceremony dedicated the lighthouse as an important historical landmark. From 1956 to 1974, the lighthouse was leased to the Lincoln County Historical Society as a museum. In 1974, Oregon State Parks initiated a thorough restoration and had it listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The lighthouse opened to the public in 1975.

On December 7, 1996, the Coast Guard relit the station’s light which is visible from six miles out to sea. The Oregon Parks and Recreation Department and the Yaquina Lights Organization jointly maintain this Private Aid to Navigation.

Currently 75,000 free tours are given a year of the structure. The lighthouse, except for the lantern room, is open for tours daily from Memorial Day weekend to September 30 from 11:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Off season hours are noon to 4:00 p.m. From November through February, the lighthouse is closed on Mondays and Tuesdays. Entrance is by donation. The phone numbers are (541) 265-4560 or (541) 265-5679.

YAQUINA HEAD LIGHTHOUSE

Located about three miles north of Newport, the Yaquina Head Lighthouse’s tower, at 93 feet high, is the tallest on the Oregon Coast. Its first-order Fresnel lens still operates. However, the original oil burning wicks have been replaced with a thousand watt globe. Since 1939, its signal has been two seconds on, two seconds off, two seconds on, 14 seconds off, 24 hours a day. It’s visible 19 miles out to sea.

Congress appropriated funds for the structure in March 1871 with construction starting that fall. Major winter storms caused problems. Two boats, trying to land supplies, overturned and lost their cargo in the rough seas that winter. Other construction supplies were offloaded at Newport then hauled six miles on an almost impassable road.

The lantern and lens arrived during the spring of 1872. Sections of the lens, built in France, were shipped through New York and portaged across Panama. More than 370,000 bricks from San Francisco were laid into the double-walled tower. That October, the keeper’s two-story wooden dwelling and an oil house were completed.

Another delay occurred in 1873 when it was discovered three of the sixteen crates filled with pieces for the lantern room had been lost in transit. New pieces had to be fabricated. Finally, on August 20, 1873, Yaquina Head’s lamp was fit for the first time. In 1923, the station added a one-story keepers’ house.

In 1918, a Signal Corps squadron, logging spruce trees to build World War I airplanes, camped near the lighthouse. Their officers petitioned the Lighthouse Service to allow the troops to visit the station. They were denied since they weren’t on official business and “it would be impractical to make such distinctions in admitting visitors.”

These restrictions were lifted after the war, and in 1924, the keepers reported nearly 10,000 visitors. A year later, regular visitor hours were posted. With more than 400,000 visitors a year, Yaquina Head has become one of the most visited lighthouses on the West Coast.

In 1933, electricity reached the station. The light’s characteristic changed from fixed to flashing. In 1938, the U.S. Coast Guard took over management. They replaced the original two-story dwelling. During World War II, 17 servicemen were stationed at Yaquina Head to keep a lookout for enemy ships.

The light became automated in 1966 allowing the last two Coast Guard keepers to leave the station. Both keepers’ dwellings and all outbuildings were demolished in 1984 leaving only the tower and adjoining workroom.

The Coast Guard closed the tower to the public for many years. In 1993, it became a part of the Yaquina Head Outstanding Natural Area managed by the Bureau of Land Management. It was again closed in 2005 for refurbishment. In July 2006, the lighthouse reopened after being repainted in its original colors of black and white.

This natural area is open year round from dawn to dusk. Several trails are available for hiking leading to views of harbor seals, seabird nesting sites, and tide pools. During the summer, some gray whales feed in shallow waters around the headland.

During the winter season, interpreters give 45-minute lighthouse tours Friday to Tuesday from noon to 4:00 on the hour. Tours are daily, except Wednesdays, during these same times throughout the summer months. Sign up for tours, limited to eight people at a time, takes place at the interpretative center. Cost is by donation.

Be sure to visit the interpretative center. It shows two movies continuously. They are “1930's Oil to Electric” and “Fixed Light to Focusing.” You’ll also find fascinating exhibits on the lighthouse’s history, management. and preservation. In another room, you’ll learn about marine mammals, sea star wasting, and creatures found on the rocky shore such as Acorn barnacles and California mussels. We saw the skull, vertebrae, and jaw bone of a gray whale. An interactive allows visitors to hear the sounds of gray whales, California sea lions, and harbor seals. We also saw a Fresnel light. It’s open 10 a.m. to 4 p.m.

Admission to this natural area is via a daily $7 fee or annual Yaquina Head Pass, an Oregon Pacific Coast Passport, or a National Parks and Federal Recreational Lands Pass. The phone number is (541) 574-3116. It is located about three miles north of Newport on Highway 101.

Those seeking to tour or photograph lighthouses will find a wealth of them on Oregon’s Coast. Between Bandon and Newport, we found several worth exploring. All provide tours and are on the National Register of Historic Places.

COQUILLE RIVER LIGHTHOUSE

Opposite Bandon, on the Coquille River’s north jetty, visitors find Coquille River Lighthouse with its unique architecture. Its a cylindrical tower attached to the east side of an elongated octagonal room. It had a large trumpet protruding from its western wall. The tower is 47 feet in height from its base, the smallest lighthouse on the Oregon coast.

When the station was completed, a long wooden walkway connected it to the keepers’ duplex located 650 feet away. A barn was situated 150 feet beyond the dwelling.

The need for this lighthouse was discovered in the mid 1800's when many vessels bypassed the area because of the rocks and shifting sands at the river’s entrance. At times, with only three feet of water over the bar, the situation proved so discouraging to captains that they kept their ships away. Maritime traffic was important since Bandon was a hub for shipping between San Francisco and Portland. The primary cargo, besides passengers, was fish and timber.

Since Bandon’s citizens wanted more maritime shipping than an occasional vessel, they lobbied to have the area improved. In 1887, Congress built a jetty on the bar’s south side creating a channel 10 to 12 feet at a high tide. Unfortunately, shoaling continued to cause problems. By 1888, it was evident that a jetty on the northern side of the river entrance and a lighthouse were essential for maritime safety.

In 1891, Congress authorized funds for the construction which started in 1895. On February 29, 1896, the lamp in the fourth-order Fresnel lens was lit for the first time. The fixed white light shone for 28 seconds with an eclipse of two seconds. It was seen for 13 miles. During the snowstorm on March 1, the fog signal was first fired up. However, sometimes due to certain weather conditions, it would fail at sea so it was replaced by a more reliable fog siren in 1910.

Two shipwrecks occurred near this lighthouse. On January 9, 1897, the schooner Moro was stuck on the bar. Even though her cargo of lumber, broom handles, and fish was tossed overboard, the ship could not be freed and became a total loss. The schooner Advance in 1905 rammed the north jetty, completed that year, but the ship was able to be saved.

Having Bandon on the river’s opposite shore eliminated the isolation felt at other Oregon coast lighthouses. The station boat was used to secure supplies and ferry the children to school. A boathouse was built in 1901 to shelter it.

By 1915, the Bureau of Lighthouses proposed moving the light and fog signal to the river’s south side. This met with resistance since ships were used to the lighthouse’s position. The move never occurred.

In September 1936, a massive fire nearly destroyed Bandon. It wiped out all but 16 of the town’s 500 buildings. The lighthouse’s keepers, who were the Langlois and Walters families, provided food and shelter for the homeless. They were the last keepers to serve since in 1939, the Coast Guard decided the lighthouse was no longer needed. It was replaced with an automated beacon at the end of the south jetty with a range of 14 miles. Today, it is still 28 seconds on and two seconds off.

The lighthouse stood abandoned for 24 years until Bullards Beach State Park was created in 1964. The lighthouse grounds were included in the park which assumed responsibility for the lighthouse. In 1976, work started to repair the lighthouse which had fallen into disrepair. Oregon State Parks and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers shared the costs and completed the renovation in 1979 when it reopened to the public. The keepers’ quarters and other outbuildings had deteriorated past the point of repair so they were removed. As part of Bandon's centennial celebration in 1991, a new solar powered light was installed in the tower. More restoration was done in 2007.

Today’s visitors can tour the lighthouse’s boiler room where they can view interpretative signs. It is open mid May through September from 11:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.

The park provides three loops of campsites, 13 yurts, and a horse camp. Boat launch facilities are used during the summer and fall seasons. A path leads along open, grassy fields and lowland forest across a plain to sand dunes. All along the path are views of the Coquille River. There are also 4.5 miles of open beach to explore.

The phone number is (541) 347-2209. The entrance to Bullards Beach State Park is on the west side of Highway 101, just north of the Coquille River Bridge. Park signs lead the way to the lighthouse.

UMPQUA RIVER LIGHTHOUSE

In 1849, the Coast Survey determined that the Umpqua River Lighthouse, located on Winchester Bay south of Reedsport, was to be among the first sixteen sites selected for West Coast lighthouses. An initial appropriation was made by Congress in 1851.

When materials arrived by ship from San Francisco in 1855, construction finally began. Because of the region’s stormy weather and problems with the local Indians, construction went slowly. It was finally finished October 10, 1857 when the third-order Fresnel lens lamp was lit. It was the first lighthouse along the Oregon coast.

The lighthouse design consisted of a Cape Cod duplex with keepers quarters on each side of the 92-foot tower from the center of the gabled roof. It was similar to other lighthouse structures that had been built at Cape Flattery and on Dungeness Spit.

The lighthouse suffered from frequent river flooding. In 1861, a gale with record mountain runoff blasted the light’s foundation. With its footings compromised, the house and tower developed a slight tilt. Another major storm in October 1883 made the situation precarious. The keepers petitioned for the lighthouse to be abandoned. In late 1884, the permission was granted. A week later the lens was removed. While workers were dismantling the iron lantern room, the tower began to shake then fell.

In 1888, Congress appropriated funds for a new lighthouse at Umpqua River as well as one at Heceta Head. The purpose was to fill in the gap between those at Cape Arago and Yaquina Head so mariners would enter the visible range of a light as they passed from another. The new light was built above the river on a 100-foot high ridge which overlooked the sand dunes on the river’s south side.

The metalwork was completed in March 21, 1892 and the tower on August 30, 1892. In February 1892, the contractor for the dwellings went bankrupt. Their bondsmen were held responsible for the difference between the original contract and the new bid. The head keeper’s double dwelling was finally finished on January 14, 1893.

In January 1893, when the illuminating apparatus and lens were to be installed, the lens’ base was found to be 15 inches short and another $200 would be needed. Funds were finally obtained in August 1894 with the new first-order Fresnel lens turned on December 31. The new tower stood 65 feet tall and had a focal point of 165 feet above sea level.

Red panels mounted on the lens created a light that flashed white twice, then once red, every 15 seconds. Every 70 minutes the keepers would have to wind up the weight that revolved the lens. Except for a brief outage caused by a 1958 fire, and the period between November 1983 and January 1985, when the lens’ mechanism failed and was repaired, the light’s red and white beam has continued to shine. It is currently on 24 hours a day.

In 1934, a generator building was built near the lighthouse, and the station was electrified. All of the buildings, except for the lighthouse, were eventually torn down.

The Douglas County Parks Department took ownership of the lighthouse and grounds in early 2010. In April 2012, the U.S. Coast Guard also gave Douglas County control of the operation and maintenance of Umpqua Lighthouse and its Fresnel lens.

The lighthouse’s location is near Umpqua Lighthouse State Park, about six miles south of Reedsport and one mile west of Highway 101. The park is open daily.

Visitors find a museum housing exhibits on Oregon’s lighthouses and the 1940-60s Coast Guard, as well as a gift shop, in a historic Coast Guard building located about 200 yards from the lighthouse. From here, volunteer docents lead lighthouse tower and grounds tours. These are available daily from May 1 to October 30 from 10:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. The phone number is (541) 271-4631. The museum is free but there is a charge for the tours.

Outside, overlooking the Pacific Ocean, check out the signage on whale watching. Whales have mostly commonly been seen here in May to June and November to December.

HECETA HEAD LIGHTHOUSE

Heceta Head Lighthouse is located at Heceta Head Lighthouse State Scenic Viewpoint on Highway 101 near milepost 178. It’s about 13 miles north of Florence and 13 miles south of Yachats. Its 56-foot tower is situated 205 feet above the ocean. Not only can you tour this lighthouse, but you can stay at the former assistant keepers’ dwelling which is now a bed and breakfast.

In 1889, Congress appropriated $80,000 for the site purchase and construction. Its purpose was to fill an unlit gap between Yaquina Head’s light and one to be built on Umpqua River. By January 1893, work was completed on two oil houses, a barn, and two Queen Anne-style dwellings. One was a home for the head keeper while his two assistants shared a duplex.

Due to a landslide at the tower site requiring additional excavation, the tower was not finished until the following August. The lamps for the first-order Fresnel lens were finally lit March 30, 1894. The light, 205 feet above the sea, flashed white for ten seconds every minute and was visible for 21 miles. It was and still is rated as the strongest light on the Oregon coast.

Reaching Heceta Head was an arduous task. The wagon road to Florence was impassable much of the year and ships could anchor near the lighthouse only in calm seas. Its remoteness led to keepers and their families hunting, fishing, and raising crops to provide for their own food. If keepers needed supplies, a neighbor hitched his Clydesdale team to a wagon for the two-day round trip. The teacher at the nearby one room schoolhouse taught all eight grades to 14 children, nine of which were keepers’ children.

When keeper Clifford Hermann arrived in 1925, the only unfinished part of the Oregon Coast Highway was between Yachats and Florence. The two towns were connected by a narrow and muddy road used mostly by mail carriers who rode horseback. Between 1930 and 1932, crews built the highway connecting the entire area.

Electricity arrived at the lighthouse station in 1934. An electric motor turned the lens while a light bulb replaced the lamp. When the second assistant’s position was eliminated, the Hermanns moved into the duplex and the single dwelling was torn down.

During World War II, the Coast Guard assigned large numbers of personnel to coastal lighthouse stations. At Heceta Head, 75 men moved into barracks and ate at a mess hall where the single dwelling had stood. They patrolled, with a dozen dogs at their sides, the beaches from Florence to Yachats. Above the lighthouse, they built a lookout tower.

On July 20, 1963, the lighthouse became automated. After that date, personnel from Oregon State Parks and the U.S. Forest Service rented the dwelling. The Forest Service eventually acquired all of the property except for the two acres retained by the Coast Guard where the lighthouse and oil houses stood. The dwelling fell into disrepair when the Forest Service failed to have the funds to maintain it.

In 1970, Lane Community College leased the home for use as classrooms. The College hired caretakers and agreed to do interior repairs in lieu of paying rent. None of the caretakers stayed long until Harry and Anne Tammen arrived in 1973. Under their watch, major changes occurred over four years to return the exterior to its appearance when the first lighthouse keepers moved there. In 1978, the home was listed on the National Historic Register.

Lane College used the assistant lighthouse keepers’ dwelling as classrooms until 1995. That year, the U.S. Forest Service made it into a self-sustaining bed and breakfast. The first floor houses an interpretative center. Tours are given Memorial Day through Labor Day, Thursday through Monday, from 11:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. The phone number is 866-547-3696.

Lighthouse tours are provided daily Memorial Day through Labor Day from 11:00 to 3:00 p.m. In the winter, the hours are 11:00 a.m. to 2:00 p.m. if the weather and staff permit. For information about these tours, call (866) 547-3416

Since 1994, the Oregon Parks Department has owned the lighthouse tower. They did a massive restoration project on it between 2011 and 2013 to return it as it would have appeared in 1894. It now operates as a Private Aid to Navigation. Daily from June through September, from noon to 3:00 on the hour, park volunteers and docents run tours of the outdoor area around the lighthouse and the tower’s ground floor.

The lighthouse, overlooking a beautiful sandy beach, can be reached via a steep half mile trail which begins at the parking area and goes past the bed and breakfast. The Viewpoint also offers caves and tide pools to explore. As part of the Oregon Islands National Wildlife Refuge, it’s home for nesting seabirds, seals, and sea lions. During the spring and early summer, you may also spot migrating whales.

The Viewpoint is a day use area with a parking fee of $5 unless you have an Oregon Parks permit. Note that from the parking lot, the view of the lighthouse is obscured. Drive south to the next overlook and park for a very good view of the lighthouse which allows for photography. We spotted sea lions at this location. A road off Highway 101 leads to the bed and breakfast.

YAQUINA BAY LIGHTHOUSE

The 1871 Yaquina Bay Lighthouse, located at Yaquina Bay State Park, is the oldest structure in Newport. It’s the second-oldest standing lighthouse on the Oregon Coast, the only existing Oregon lighthouse with attached living quarters, and the only historic wood frame Oregon lighthouse still standing. Its beacon, produced by an oil lamp within a fifth order Fresnel lens, shone for only three years, 1871-1874.

In 1870, Congress authorized funding for a lighthouse on Yaquina Bay. The action was taken despite the advice of Colonel R. S. Stockton, Lighthouse Service district engineer. He advocated that a first-order light should be built at Yaquina Head instead of a harbor light on the bay. His advice was ignored, and by the end of October 1871, the new station was finished.

It was a two-story building that included a basement. Chimneys stood near each end of the gabled roof. A three-story tower rose from the building’s rear housing a small, fifth-order Fresnel lens. On November 3, 1871, Charles Peirce, the station’s only keeper, lit the whale oil lamp in the fixed lens. It had a visibility of 12 miles from shore.

The Lighthouse Board reconsidered Stockton’s advice even before the lamp was lit. It decided to construct a new lighthouse on Yaquina Head. In August 1873, a first-order light went into operation there. The new light had a range of 22 miles. The Yaquina Bay light was ordered discontinued and was lit for the last time on October 1, 1874.

Yaquina Bay remained empty for 14 years and fell into disrepair. The station was offered for sale in 1877, but the price offered was too low and the bid was withdrawn. A year later, the roof and outside sheathing were removed to prevent the building from falling apart.

There was talk of reactivating the lighthouse when the railroad arrived at the bay, but this never happened. Instead, small unmanned lanterns were added to assist night bar crossings, and the old lighthouse was officially listed as a “day beacon.”

Several different tenants used the station. From 1888 to 1896, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers used it as a home for John Polhemus, the engineer in charge of the construction of the river’s jetties. From 1906 to 1915, the U.S. Lifesaving Service used the lighthouse as quarters and as lookout. During this period, they built the eight-story steel observation tower that still stands next to the original lighthouse. In 1933, they abandoned the light.

In 1934, the State of Oregon acquired the lighthouse and its surrounding property for public highway, park, and picnic purposes. The Division decided in 1946 the building should be demolished since they were unwilling to make repairs. This led to the formation in 1948 of the Lincoln County Historical Society to save the lighthouse. With the help of the Oregon Historical Society, they were successful. By 1955, the plans for demolition were abandoned.

In 1956, a ceremony dedicated the lighthouse as an important historical landmark. From 1956 to 1974, the lighthouse was leased to the Lincoln County Historical Society as a museum. In 1974, Oregon State Parks initiated a thorough restoration and had it listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The lighthouse opened to the public in 1975.

On December 7, 1996, the Coast Guard relit the station’s light which is visible from six miles out to sea. The Oregon Parks and Recreation Department and the Yaquina Lights Organization jointly maintain this Private Aid to Navigation.

Currently 75,000 free tours are given a year of the structure. The lighthouse, except for the lantern room, is open for tours daily from Memorial Day weekend to September 30 from 11:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Off season hours are noon to 4:00 p.m. From November through February, the lighthouse is closed on Mondays and Tuesdays. Entrance is by donation. The phone numbers are (541) 265-4560 or (541) 265-5679.

YAQUINA HEAD LIGHTHOUSE

Located about three miles north of Newport, the Yaquina Head Lighthouse’s tower, at 93 feet high, is the tallest on the Oregon Coast. Its first-order Fresnel lens still operates. However, the original oil burning wicks have been replaced with a thousand watt globe. Since 1939, its signal has been two seconds on, two seconds off, two seconds on, 14 seconds off, 24 hours a day. It’s visible 19 miles out to sea.

Congress appropriated funds for the structure in March 1871 with construction starting that fall. Major winter storms caused problems. Two boats, trying to land supplies, overturned and lost their cargo in the rough seas that winter. Other construction supplies were offloaded at Newport then hauled six miles on an almost impassable road.

The lantern and lens arrived during the spring of 1872. Sections of the lens, built in France, were shipped through New York and portaged across Panama. More than 370,000 bricks from San Francisco were laid into the double-walled tower. That October, the keeper’s two-story wooden dwelling and an oil house were completed.

Another delay occurred in 1873 when it was discovered three of the sixteen crates filled with pieces for the lantern room had been lost in transit. New pieces had to be fabricated. Finally, on August 20, 1873, Yaquina Head’s lamp was fit for the first time. In 1923, the station added a one-story keepers’ house.

In 1918, a Signal Corps squadron, logging spruce trees to build World War I airplanes, camped near the lighthouse. Their officers petitioned the Lighthouse Service to allow the troops to visit the station. They were denied since they weren’t on official business and “it would be impractical to make such distinctions in admitting visitors.”

These restrictions were lifted after the war, and in 1924, the keepers reported nearly 10,000 visitors. A year later, regular visitor hours were posted. With more than 400,000 visitors a year, Yaquina Head has become one of the most visited lighthouses on the West Coast.

In 1933, electricity reached the station. The light’s characteristic changed from fixed to flashing. In 1938, the U.S. Coast Guard took over management. They replaced the original two-story dwelling. During World War II, 17 servicemen were stationed at Yaquina Head to keep a lookout for enemy ships.

The light became automated in 1966 allowing the last two Coast Guard keepers to leave the station. Both keepers’ dwellings and all outbuildings were demolished in 1984 leaving only the tower and adjoining workroom.

The Coast Guard closed the tower to the public for many years. In 1993, it became a part of the Yaquina Head Outstanding Natural Area managed by the Bureau of Land Management. It was again closed in 2005 for refurbishment. In July 2006, the lighthouse reopened after being repainted in its original colors of black and white.

This natural area is open year round from dawn to dusk. Several trails are available for hiking leading to views of harbor seals, seabird nesting sites, and tide pools. During the summer, some gray whales feed in shallow waters around the headland.

During the winter season, interpreters give 45-minute lighthouse tours Friday to Tuesday from noon to 4:00 on the hour. Tours are daily, except Wednesdays, during these same times throughout the summer months. Sign up for tours, limited to eight people at a time, takes place at the interpretative center. Cost is by donation.

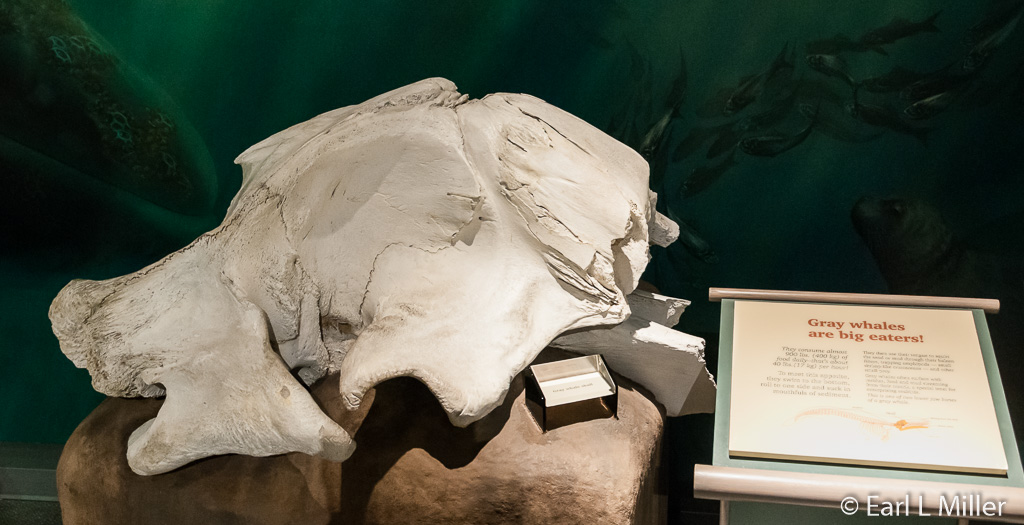

Be sure to visit the interpretative center. It shows two movies continuously. They are “1930's Oil to Electric” and “Fixed Light to Focusing.” You’ll also find fascinating exhibits on the lighthouse’s history, management. and preservation. In another room, you’ll learn about marine mammals, sea star wasting, and creatures found on the rocky shore such as Acorn barnacles and California mussels. We saw the skull, vertebrae, and jaw bone of a gray whale. An interactive allows visitors to hear the sounds of gray whales, California sea lions, and harbor seals. We also saw a Fresnel light. It’s open 10 a.m. to 4 p.m.

Admission to this natural area is via a daily $7 fee or annual Yaquina Head Pass, an Oregon Pacific Coast Passport, or a National Parks and Federal Recreational Lands Pass. The phone number is (541) 574-3116. It is located about three miles north of Newport on Highway 101.

Coquille River Lighthouse as Seen From the Southern Jetty

Coquille River Lighthouse Close Up

Area Around Coquille River Lighthouse

Umpqua River Lighthouse

Heceta Head Bed and Breakfast - View From Parking Lot

View of Heceta Head Lighthouse from Beach

Heceta Head Lighthouse View from Overlook

Yaquina Bay Lighthouse with Coast Guard Observation Tower

Yaquina Head Lighthouse

Yaquina Head

Interpretation Center at Yaquina Head Outstanding Natural Area

Display on Lighthouse at Interpretation Center

Natural History Display at Interpretation Center

Gray Whale Skull

Gray Whale Vertebrae

Gray Whale Jaw

Fresnel Lens