Hello Everyone,

Wall, South Dakota is the gateway for investigating Badlands National Park, located about ten miles away. Its 244,000 acres consist of a landscape where colorful pinnacles and spires, massive buttes, and deep gorges were formed over millions of years by erosion and deposition. They are nearly surrounded by Buffalo Gap National Grassland, one of the country’s areas of a mixed-grass prairie. These layered rock formations delight visitors with their bands of color.

The park consists of three sections. It is the northern part that is most commonly explored. It includes the 40-mile Badlands Loop Road with its many overlooks and trailheads. Cedar Pass is the location of the year-round Ben Reifel Visitor Center and the seasonal Cedar Pass Lodge. The other two areas, Stronghold and Palmer Creek units, are located on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. Both of those operate under a cooperative agreement between the Oglala Lakota and the National Park Service. The Stronghold unit does offer a seasonal visitor center.

HOW THE LAND WAS SHAPED

Approximately 69 to 75 million years ago, during the Cretaceous Period, a shallow sea covered the area referred to as the Great Plains. It was home to all kinds of marine life. The bottom of that sea, once a black mud, is now the gray-black sedimentary rock known as Pierre Shale. It has been the source of rich marine fossil finds including clams, crabs, mosasaurs, and extinct cephalopods called baculites. Baculites are described in the Badlands brochure as “a squidlike body with a long cylindrical shell tightly coiled at one end.” Other cephalods found in the Badlands are belemnites and ancient versions of the Nautilus. Ammonites have also been discovered which are closely related to baculites. Among the most common fossils found in the Badlands are turtles.

Eons later, the landscape drastically changed as the Rocky Mountains and Black Hills were built. The climate became warm and humid. As the land under the sea rose, the water retreated and drained away. Exposure to a tropical environment and the weathering process, including chemicals from decaying plants, produced a yellow soil which is seen today at Yellow Mounds.

Between 34 and 37 million years ago, the greyish Chadron Formation was deposited. Instead of the sea, a river flood plain existed. A new layer was added to the plain each time the rivers (similar to today’s inland deltas) flooded. Eventually a lush, subtropical forest covered the land. Fossils found from this period consist of alligators and mammals including a rhinoceros-like mammal called a titanothere, the largest known Badlands fossil. When visiting the Badlands today, to see this Formation, look for low, minimally vegetated, grey or greenish-gray mounds.

The Oligocene Epoch between 23 and 34 million years ago is accountable for the tannish brown Brule Formation. It was during this period that the forests gave way to a savannah when the climate began to dry and cool. Geologists have found bands of sandstone interspersed among layers. These marked the flow of rivers from the Black Hills. These widespread horizontal color bandings are mostly yellow-beige and pinkish-red.

The same forces that shaped the Badlands embedded fossils there millions of years ago. The site contains the world’s richest bed of Oligocene and late Eocene (34 to 37 million years ago) mammal fossils. More than 250 fossils of mammal species have been documented in the Badlands. These have included the three-toed horse, nimravids or false saber-toothed tigers, camels, and the Protoceras, which was built more like a small camel or pronghorn. Males had six horns on their heads and also sported elongated canines. Oreodonts have also been found. These were about the size of a sheep but ran and jumped like today’s domesticated pig. Surprisingly, they were more closely related to camels.

More than a million fossils have been found. With continued erosion, new fossils are constantly being uncovered. It is legal for only paleontologists to remove any of these from the park.

During the Oligocene Epoch, a layer of thick volcanic ash was deposited. This Rockyford Ash marks the boundary between the Brule Formation and the lighter colored Sharps Formation. The Sharps Formation, dating between 28 and 30 million years ago, was deposited by wind and water. In addition, volcanic eruptions to the west of this formation continued to supply ash. It’s the Brule and Sharps formations that form the more rugged peaks and canyons of the Badlands.

Deposition and erosion are continuing today. In many places, the Badlands are eroding at the rate of one inch a year. When the Badlands erode away completely, the area will look like the rest of western South Dakota with rounded prairie hills in the Pierre shale. This erosion has revealed sedimentary layers of different colors: purple (oxidized manganese), yellow (shale), tan and gray (mixture of silt, clay, and ash), red and orange (iron oxides), and white (volcanic ash).

Extending generally from west to east, visitors find a ridge or “wall” 80 miles long that forms the park’s backbone. This formation gave the town of Wall its name.

HUMAN CULTURE

The first inhabitants, the Paleo Indians, who were mammoth hunters, lived in the area during the Ice Age around 11,000 to 12,000 years ago. They were followed by the Arikara Indians, who camped around 1500 A.D. More than 100 archaeological sites have been found with one of the larger sites in the vicinity of Ancient Hunters Overlook. Evidence of charcoal, pot shards, and broken buffalo bones have been discovered. By about 1700 A.D., other tribes moved into the territory. These included the Cheyenne, Kiowa, Pawnee, Crow, and Sioux.

The Sioux since 1670 had been migrating south and westward from the headwaters of the Mississippi River. The Oglala and Brule, tribes of the Sioux nation, arrived around 1775 to occupy the Badlands. It was the Lakotas who named the area “mako sica” or badlands. Although they found this area very difficult to travel through, they became nomadic depending on buffalo for their almost every need. About 150 years ago, the Great Sioux Nation displaced other tribes from the northern prairie.

Early French Canadian trappers were the first white men to see the Badlands. They called it “les mauvaises terres a traverser” meaning “Bad land to travel across.” The Jedemiah Smith party traveled through the area in 1823 and was almost stopped by lack of water. Until 1846, there are no known records of travel into the Badlands.

In 1846, Dr. Hiram A. Prout of St. Louis published the first account of a Badlands fossil. It was the lower jaw of a titanothere. Dr. Joseph Leidy, the following year, described a skull of a fossil camel. He later became an authority on Badlands fossils. These two reports aroused the interest of other paleontologists. Prout’s specimen and Leidy’s camel are housed at the Smithsonian.

Edward T. Welsh, who is an interpretative educational ranger for the Badlands, told me, “This was the first time a camel was found in North America, and overall the oldest camel known at the time. Poebrotherium was named in 1847. Leidy would also name the first dinosaur (Hadrosaurus faulki from Haddonfield, New Jersey) in North America. But that wouldn’t happen until 1858.”

By 1869, Dr. Leidy had discovered fossils of approximately 500 oreodonts and many other animals. The Smithsonian Institution, the American Museum of Natural History, and Yale and Princeton Universities sent out teams to excavate fossils for their collections. Welsh added, “Discoveries made by Prout and Leidy make the Badlands the birthplace of paleontology in the American West.”

The South Dakota School of Mines and Technology in Rapid City also collected fossils in the Badlands. Today you can see many of their fossils by visiting the school’s Museum of Geology. (See our December 18, 2019 article). This includes an oreodont, touted by the museum, as pregnant with twins.

Ranching developed by 1890. Unfortunately, the harsh winter weathers, particularly the May blizzard of 1905, killed thousands of cattle. With the Homestead Act of 1862 and the Gold Rush of 1874, homesteaders and miners settled on the land. The Sioux retaliated more and more against the many settlers, culminating with the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868.

With this treaty, the Sioux (Lakota) Indian tribe members were removed from their homes to live at Pine Ridge Reservation. It remains one of their most sacred places. The treaty prohibited settlers or miners from entering the Black Hills without authorization. In return, the Sioux promised to stop their hostilities.

This treaty was broken in 1874 when General George Custer’s expedition into the Black Hills led to the discovery of gold. The metal was discovered on June 30, 1874. Soon miners were swarming into the area. Federal soldiers tried to cordon off the Black Hills but to no avail.

A prophet named Wovoka began organizing “Ghost Dances” on the Stronghold Table in the Badlands. His followers wore “Ghost Shirts," believed to be bulletproof, while performing these dances. The ritual was to restore the area to its pre colonial state. In 1890, the final Ghost Dance took place, A few weeks later, 250 to 300 Lakota were massacred by United States Cavalry at Wounded Knee, 25 miles south. Today the Oglala Lakota nation is the second largest Indian reservation in the United States.

As early as 1909, the South Dakota legislature had petitioned the United States government to establish the Badlands as a national park. A leader on this was South Dakota Senator, and later Governor, Peter Norbeck, who became known for his support for Custer State Park and Mount Rushmore. President Franklin D. Roosevelt proclaimed the establishment of Badlands National Monument on January 25, 1939. The park was established to protect the fossils and the scenery.

In 1976, another federal bill added more than 130,000 acres of the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation to the boundaries of Badlands National Park. These are lands that were used as a bombing and gunnery range during World War II. Undetonated bombs are still being discovered in the area today. On November 10, 1978, under President Jimmy Carter, the Badlands became a national park.

VISITOR CENTER AND LOOP DRIVE

Plan on traveling the 240 Badlands Loop Road’s 40-mile drive. It takes about an hour without stops. Numerous overlooks, where you can pause to admire the scenery, are found. You’ll want to drive this at least twice - once in the daytime and once at sunset to photograph the coloration changes of the rocks and see wildlife. Another great time to see the animals is on an early morning drive.

Stop at the Ben Reifel Visitor Center. It was named after the first American Indian elected to Congress, Ben Reifel. You can start your visit by viewing the park film, Land of Stone and Light which is shown throughout the day. Short videos cover such topics as homesteading and swift foxes.

Rangers staff the Center daily during hours of operation and are pleased to answer visitors’ questions. Ranger-led talks and walks are offered from Memorial Day to Labor Day. Youngsters can become a Junior Ranger. The gift shop is an excellent source for books.

I do not normally suggest books. However, I found Badlands National Park: Official Road Guide to be invaluable. It describes in detail the overlooks and points of interest in all park sections, hikes, roadside plants, and wildlife. It can be purchased at Cedar Lodge or the visitor center. The book costs three dollars.

Be sure to visit the Center’s fossil preparation lab which is open from 9:00 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. daily from the second week in June through the third week in September. After the summer, they put fossils in a collection facility for storage. You can watch paleontologists work on fossils found at various sites around the park. Feel free to ask questions.

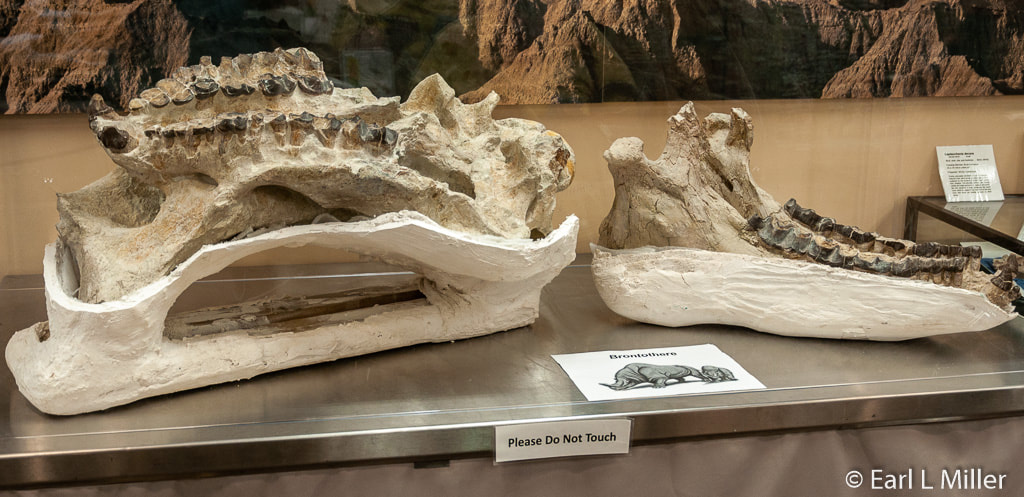

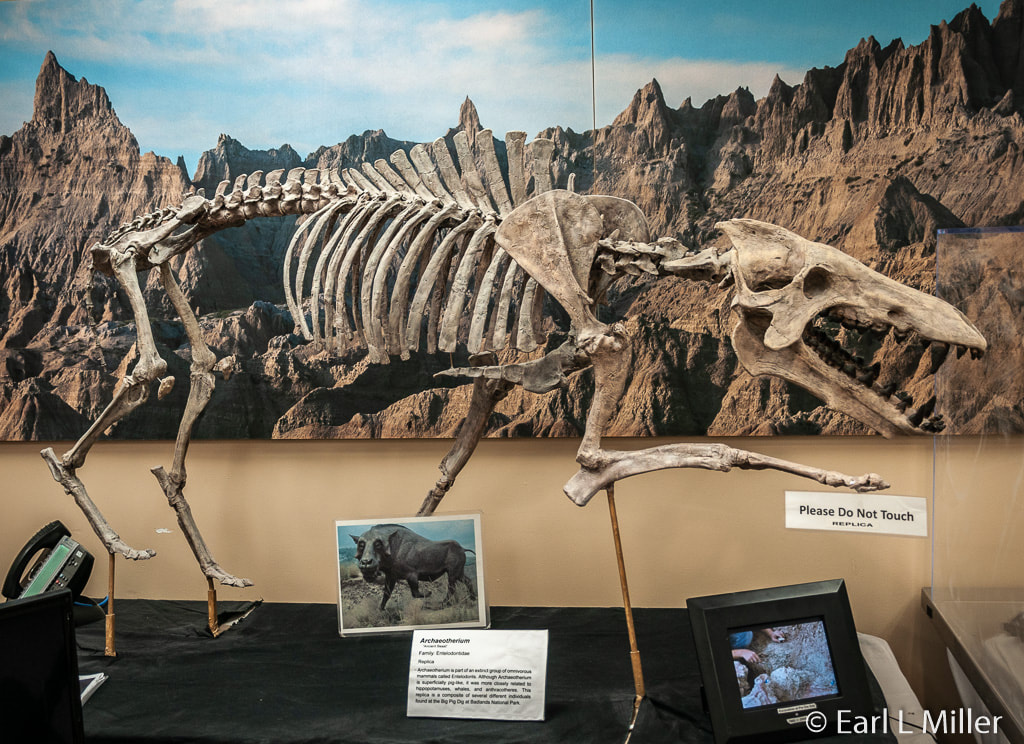

We watched Mary Carpenter, who was working on a Leptomeryx (deer) skull’s bottom jaw. This animal lived 31 million years ago and was related to the mouse deer. We also saw the skull of an original Brontothere, a large hoofed herbivorous animal; the skull of a nimravid; and the skull and replica of the skeleton of an Archaeotherium, a piglike creature. Look for the comparison between modern and fossil tortoises.

She explained that they use microscopes, even on larger fossils, with a magnification of up to 40x. They push the sediment through a fine screen and then wash it. They keep the sediment. Sometimes they find prehistoric scat. They use air pressure to clean the specimens. The pressure per square inch ranges from 10 to 90, depending upon the tool they are using.

VISITOR CENTER EXHIBITS

One exhibit relates erosion in the Badlands a million years ago, 500,000 years ago, and now. A million years ago, rocks washed off the Rocky Mountains and Black Hills transforming the Badlands. Around 500,000 years ago, glacial rivers flowed near the Badlands with the streams eroding rocks. Pinnacles and other formations began to evolve. Now there is constant erosion, and a million years from today, most of the soft rock will have eroded.

There are several dioramas. Jungle on a Seabed covers the shallow sea of the Cretaceous Period. It relates how a jungle sprang up 65 million years ago.

Winter Bison is a scene of bison and wolves. The wolves look like they are getting ready to attack.

Another depicts Death in Drying Grasslands. A hornless rhino in a muddy watering hole attracts an Archeotherium, a large piglike creature more closely related to a hippopotamus or whale. A composite of at least 17 different Archeotheriums was found at the Badlands’ Pig Dig. More than 19,000 specimens of various animals, but primarily rhinos and big pigs, have been recovered from the Pig Dig site during 15 years of excavation.

The diorama Dawn of the Prairie depicts that the land is drier now. A Nimravidae, a false saber toothed cat charges after a herd of Mesohippus, three-toed horses about the size of Collie dogs. They gallop away from the predator. Unconcerned by the commotion, a group of Leptomeryx (deer-like mammals the size of cats) feeds on shrubs and grasses as they move through the grasslands.

Another A Summer Afternoon Nearly Million 40 Years Ago takes place in an ancient forest. A titanothere grazes while alligators prowl and tortoises bask in the sun. A flock of oreodonts (sheep-like herbivores) keep an eye out for nearby predators. The oreodont has been the most common fossil found in the Badlands indicating they used to live in communities.

An interactive, Teeth Tell Tales, has visitors guess whether the teeth came from a carnivore or a herbivore. Examples are an alligator and an oreodont. Look for the Titanothere skull. Several of these species evolved in the Badlands over millions of years. They are distinguished by the size and shape of the protrusions on their skull. A full-grown Titanothere had a brain about the size of a human fist.

Prairie Wilderness describes the mixed grass prairie on the western edge of the park. The sign points out that a lot of the prairie has been lost due to land development and grazing of cattle and sheep. More panels cover those who passed through the area: French explorers, Lewis and Clark, and traders. Additional ones describe how hunters killed mammoths, the Lakota, the contest for the land, and homesteading. Look for the case of Lakota art and beaded items such as moccasins.

ENJOYING THE WILDLIFE

The Badlands are home to the largest mixed grass prairie in the National Park System. It is almost surrounded by Buffalo Gap National Grassland. A variety of wildlife roams this area. One can see bison, pronghorn, mule and whitetail deer, prairie dogs, coyotes, butterflies, turtles, and extensive bird species.

Roberts Prairie Dog Town is located five miles down from the Loop Road on Sage Creek Rim Road. Beware that this is a gravel road.

Named after a family that once homesteaded in the area, it is the largest accessible black-tailed prairie dog town in the park. It’s an ecology where you might see burrowing owls who use the burrows for their nests. Perhaps, you might see a hungry coyote, badger, hawk, or golden eagle looking for its dinner. Black-footed ferrets are nocturnal and can be seen around prairie dog towns at night. Prairie dogs comprise 90 percent of their diet.

We also saw American buffalo known as bison along Sage Road. At one time, 60 million bison roamed the territory. The American Indians depended upon all parts of the animal. With the coming of the railroad and the extent of homesteading, the animals were gone from this landscape by the 1880s. In 1963, they were reintroduced into the Sage Creek basin. Because of the fear of brucellosis, the animals are contained within 64,000 acres to keep them from mingling with cattle instead of being allowed to free-range. However, no bison has tested positive for brucellosis.

As you drive the Loop Road, you are likely to find bighorn sheep. The males have larger horns than the females. They enjoy the steep, rocky terrain because they are mountain climbers. The last known bighorn sheep was shot in the South Unit in 1926. They were reintroduced in 1964 in the Pinnacles and the Sheep Mountain areas. In 1996, they were relocated to the Cedar Pass area near the park headquarters.

If you pause between Big Foot and Dillon Passes, you may find pronghorn grazing in small bands on the open grasslands. This animal is smaller than a deer. It is named for the shape of its horns - one that ends in a short prong while the other is longer with a curved hook. It is the swiftest runner of all North American animals as it can reach speeds up to 55 mph.

A bird you are likely to see is the black-billed magpie which is often spotted around the park’s picnic sites and in front of the Ben Reifel Visitor Center. It is recognizable by its black and white coloring, iridescent green spread through its wings, and its long tail. When it flies, large white patches on its wing are visible.

Turkey vultures are often seen soaring around the Badland’s buttes. They’re about the size of an eagle but have a bald red head and a white bill. They are black or dark brown with white around the edges of their wings.

The Wall area is good for birding. You might spot black-capped chickadees and cedar waxwings. During the summer, cliff swallows migrate from their winter grounds in South America. Golden eagles and prairie falcons nest high on the cliffs and soar over the Badlands year round. Rock pigeons nest on pinnacles and ridges.

DINING AND SLEEPING

The Cedar Pass Lodge, the only lodging and restaurant in the park, is open from late April to the end of October. Hours vary so it is best to check out that information on the Cedar Pass Lodge web site. When you go for a meal, make sure they have your name on their list or the wait can be long. Lodging is at rustic cabins which book up fast so it is necessary to contact the lodge directly for reservations. Their telephone number is (877) 386-4383.

HIKING AND CAMPING

The primitive Sage Creek Campground is located in the North Unit off of the Sage Creek Rim Road. Though open year round, its sites temporarily close after winter storms and spring rains. It offers pit toilets, covered picnic tables, but no water. It is on a first come, first serve basis with a 14-day limit.

At the Cedar Pass Campground, camping costs $22 plus tax for two people, per night, with no hookups. If you want a site with electricity, the fee is $37 plus tax for two people per night. Winter camping fees are $15 plus tax. Ranger talks occur during the summer at the campground amphitheater. It contains cold running water, flush toilets, picnic tables, coin operated showers, and trash containers. A dump station is available for $1 per use. There are 96 sites. You can reserve on the Cedar Pass Lodge site.

Note: Campgrounds with hookups, though not part of the park, are located in Wall, South Dakota. That is where we stayed.

Hikes vary in length as well as requiring various degrees of fitness and experience. Check with the rangers at Ben Reifel Visitor Center to find which of the eight hikes are suitable for you.

The Fossil Exhibit Trail is a .25 miles long round trip and takes 20 minutes. This fully accessible trail features fossil exhibits.

The Window Trail is another easy .25 miles long round trip taking 20 minutes. It leads to a natural window in the Badlands Wall with a view of an eroded canyon.

The park recommends the following. Carry enough water, two quarts per person per each two-hour hike. Wear sturdy boots or shoes, a hat, and sunglasses. Keep a distance of at least 100 yards from all wildlife you encounter during your hike. Leave rocks, fossils, plants, and animals as you find them.

DETAILS:

The Badlands National Park address is 25216 Ben Reifel Road, Interior, South Dakota 57750. The telephone number is (605) 433-5361. The fee for a private vehicle (all occupants) is $20 for a week. Individuals hiking or biking are charged $10 for seven days while it is $10 for a motorcycle. Entry fees are collected year round. If stations are closed, fees can be paid at an automated fee station in the visitor center. National passes are accepted - senior, access, and military.

The park is open from noon to midnight daily. The Ben Reifel Visitor Center has winter and summer hours. Winter hours are 8:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. From mid-April to mid-May and early September to late October, the hours are 8:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Summer hours are 7:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m.

Wall, South Dakota is the gateway for investigating Badlands National Park, located about ten miles away. Its 244,000 acres consist of a landscape where colorful pinnacles and spires, massive buttes, and deep gorges were formed over millions of years by erosion and deposition. They are nearly surrounded by Buffalo Gap National Grassland, one of the country’s areas of a mixed-grass prairie. These layered rock formations delight visitors with their bands of color.

The park consists of three sections. It is the northern part that is most commonly explored. It includes the 40-mile Badlands Loop Road with its many overlooks and trailheads. Cedar Pass is the location of the year-round Ben Reifel Visitor Center and the seasonal Cedar Pass Lodge. The other two areas, Stronghold and Palmer Creek units, are located on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. Both of those operate under a cooperative agreement between the Oglala Lakota and the National Park Service. The Stronghold unit does offer a seasonal visitor center.

HOW THE LAND WAS SHAPED

Approximately 69 to 75 million years ago, during the Cretaceous Period, a shallow sea covered the area referred to as the Great Plains. It was home to all kinds of marine life. The bottom of that sea, once a black mud, is now the gray-black sedimentary rock known as Pierre Shale. It has been the source of rich marine fossil finds including clams, crabs, mosasaurs, and extinct cephalopods called baculites. Baculites are described in the Badlands brochure as “a squidlike body with a long cylindrical shell tightly coiled at one end.” Other cephalods found in the Badlands are belemnites and ancient versions of the Nautilus. Ammonites have also been discovered which are closely related to baculites. Among the most common fossils found in the Badlands are turtles.

Eons later, the landscape drastically changed as the Rocky Mountains and Black Hills were built. The climate became warm and humid. As the land under the sea rose, the water retreated and drained away. Exposure to a tropical environment and the weathering process, including chemicals from decaying plants, produced a yellow soil which is seen today at Yellow Mounds.

Between 34 and 37 million years ago, the greyish Chadron Formation was deposited. Instead of the sea, a river flood plain existed. A new layer was added to the plain each time the rivers (similar to today’s inland deltas) flooded. Eventually a lush, subtropical forest covered the land. Fossils found from this period consist of alligators and mammals including a rhinoceros-like mammal called a titanothere, the largest known Badlands fossil. When visiting the Badlands today, to see this Formation, look for low, minimally vegetated, grey or greenish-gray mounds.

The Oligocene Epoch between 23 and 34 million years ago is accountable for the tannish brown Brule Formation. It was during this period that the forests gave way to a savannah when the climate began to dry and cool. Geologists have found bands of sandstone interspersed among layers. These marked the flow of rivers from the Black Hills. These widespread horizontal color bandings are mostly yellow-beige and pinkish-red.

The same forces that shaped the Badlands embedded fossils there millions of years ago. The site contains the world’s richest bed of Oligocene and late Eocene (34 to 37 million years ago) mammal fossils. More than 250 fossils of mammal species have been documented in the Badlands. These have included the three-toed horse, nimravids or false saber-toothed tigers, camels, and the Protoceras, which was built more like a small camel or pronghorn. Males had six horns on their heads and also sported elongated canines. Oreodonts have also been found. These were about the size of a sheep but ran and jumped like today’s domesticated pig. Surprisingly, they were more closely related to camels.

More than a million fossils have been found. With continued erosion, new fossils are constantly being uncovered. It is legal for only paleontologists to remove any of these from the park.

During the Oligocene Epoch, a layer of thick volcanic ash was deposited. This Rockyford Ash marks the boundary between the Brule Formation and the lighter colored Sharps Formation. The Sharps Formation, dating between 28 and 30 million years ago, was deposited by wind and water. In addition, volcanic eruptions to the west of this formation continued to supply ash. It’s the Brule and Sharps formations that form the more rugged peaks and canyons of the Badlands.

Deposition and erosion are continuing today. In many places, the Badlands are eroding at the rate of one inch a year. When the Badlands erode away completely, the area will look like the rest of western South Dakota with rounded prairie hills in the Pierre shale. This erosion has revealed sedimentary layers of different colors: purple (oxidized manganese), yellow (shale), tan and gray (mixture of silt, clay, and ash), red and orange (iron oxides), and white (volcanic ash).

Extending generally from west to east, visitors find a ridge or “wall” 80 miles long that forms the park’s backbone. This formation gave the town of Wall its name.

HUMAN CULTURE

The first inhabitants, the Paleo Indians, who were mammoth hunters, lived in the area during the Ice Age around 11,000 to 12,000 years ago. They were followed by the Arikara Indians, who camped around 1500 A.D. More than 100 archaeological sites have been found with one of the larger sites in the vicinity of Ancient Hunters Overlook. Evidence of charcoal, pot shards, and broken buffalo bones have been discovered. By about 1700 A.D., other tribes moved into the territory. These included the Cheyenne, Kiowa, Pawnee, Crow, and Sioux.

The Sioux since 1670 had been migrating south and westward from the headwaters of the Mississippi River. The Oglala and Brule, tribes of the Sioux nation, arrived around 1775 to occupy the Badlands. It was the Lakotas who named the area “mako sica” or badlands. Although they found this area very difficult to travel through, they became nomadic depending on buffalo for their almost every need. About 150 years ago, the Great Sioux Nation displaced other tribes from the northern prairie.

Early French Canadian trappers were the first white men to see the Badlands. They called it “les mauvaises terres a traverser” meaning “Bad land to travel across.” The Jedemiah Smith party traveled through the area in 1823 and was almost stopped by lack of water. Until 1846, there are no known records of travel into the Badlands.

In 1846, Dr. Hiram A. Prout of St. Louis published the first account of a Badlands fossil. It was the lower jaw of a titanothere. Dr. Joseph Leidy, the following year, described a skull of a fossil camel. He later became an authority on Badlands fossils. These two reports aroused the interest of other paleontologists. Prout’s specimen and Leidy’s camel are housed at the Smithsonian.

Edward T. Welsh, who is an interpretative educational ranger for the Badlands, told me, “This was the first time a camel was found in North America, and overall the oldest camel known at the time. Poebrotherium was named in 1847. Leidy would also name the first dinosaur (Hadrosaurus faulki from Haddonfield, New Jersey) in North America. But that wouldn’t happen until 1858.”

By 1869, Dr. Leidy had discovered fossils of approximately 500 oreodonts and many other animals. The Smithsonian Institution, the American Museum of Natural History, and Yale and Princeton Universities sent out teams to excavate fossils for their collections. Welsh added, “Discoveries made by Prout and Leidy make the Badlands the birthplace of paleontology in the American West.”

The South Dakota School of Mines and Technology in Rapid City also collected fossils in the Badlands. Today you can see many of their fossils by visiting the school’s Museum of Geology. (See our December 18, 2019 article). This includes an oreodont, touted by the museum, as pregnant with twins.

Ranching developed by 1890. Unfortunately, the harsh winter weathers, particularly the May blizzard of 1905, killed thousands of cattle. With the Homestead Act of 1862 and the Gold Rush of 1874, homesteaders and miners settled on the land. The Sioux retaliated more and more against the many settlers, culminating with the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868.

With this treaty, the Sioux (Lakota) Indian tribe members were removed from their homes to live at Pine Ridge Reservation. It remains one of their most sacred places. The treaty prohibited settlers or miners from entering the Black Hills without authorization. In return, the Sioux promised to stop their hostilities.

This treaty was broken in 1874 when General George Custer’s expedition into the Black Hills led to the discovery of gold. The metal was discovered on June 30, 1874. Soon miners were swarming into the area. Federal soldiers tried to cordon off the Black Hills but to no avail.

A prophet named Wovoka began organizing “Ghost Dances” on the Stronghold Table in the Badlands. His followers wore “Ghost Shirts," believed to be bulletproof, while performing these dances. The ritual was to restore the area to its pre colonial state. In 1890, the final Ghost Dance took place, A few weeks later, 250 to 300 Lakota were massacred by United States Cavalry at Wounded Knee, 25 miles south. Today the Oglala Lakota nation is the second largest Indian reservation in the United States.

As early as 1909, the South Dakota legislature had petitioned the United States government to establish the Badlands as a national park. A leader on this was South Dakota Senator, and later Governor, Peter Norbeck, who became known for his support for Custer State Park and Mount Rushmore. President Franklin D. Roosevelt proclaimed the establishment of Badlands National Monument on January 25, 1939. The park was established to protect the fossils and the scenery.

In 1976, another federal bill added more than 130,000 acres of the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation to the boundaries of Badlands National Park. These are lands that were used as a bombing and gunnery range during World War II. Undetonated bombs are still being discovered in the area today. On November 10, 1978, under President Jimmy Carter, the Badlands became a national park.

VISITOR CENTER AND LOOP DRIVE

Plan on traveling the 240 Badlands Loop Road’s 40-mile drive. It takes about an hour without stops. Numerous overlooks, where you can pause to admire the scenery, are found. You’ll want to drive this at least twice - once in the daytime and once at sunset to photograph the coloration changes of the rocks and see wildlife. Another great time to see the animals is on an early morning drive.

Stop at the Ben Reifel Visitor Center. It was named after the first American Indian elected to Congress, Ben Reifel. You can start your visit by viewing the park film, Land of Stone and Light which is shown throughout the day. Short videos cover such topics as homesteading and swift foxes.

Rangers staff the Center daily during hours of operation and are pleased to answer visitors’ questions. Ranger-led talks and walks are offered from Memorial Day to Labor Day. Youngsters can become a Junior Ranger. The gift shop is an excellent source for books.

I do not normally suggest books. However, I found Badlands National Park: Official Road Guide to be invaluable. It describes in detail the overlooks and points of interest in all park sections, hikes, roadside plants, and wildlife. It can be purchased at Cedar Lodge or the visitor center. The book costs three dollars.

Be sure to visit the Center’s fossil preparation lab which is open from 9:00 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. daily from the second week in June through the third week in September. After the summer, they put fossils in a collection facility for storage. You can watch paleontologists work on fossils found at various sites around the park. Feel free to ask questions.

We watched Mary Carpenter, who was working on a Leptomeryx (deer) skull’s bottom jaw. This animal lived 31 million years ago and was related to the mouse deer. We also saw the skull of an original Brontothere, a large hoofed herbivorous animal; the skull of a nimravid; and the skull and replica of the skeleton of an Archaeotherium, a piglike creature. Look for the comparison between modern and fossil tortoises.

She explained that they use microscopes, even on larger fossils, with a magnification of up to 40x. They push the sediment through a fine screen and then wash it. They keep the sediment. Sometimes they find prehistoric scat. They use air pressure to clean the specimens. The pressure per square inch ranges from 10 to 90, depending upon the tool they are using.

VISITOR CENTER EXHIBITS

One exhibit relates erosion in the Badlands a million years ago, 500,000 years ago, and now. A million years ago, rocks washed off the Rocky Mountains and Black Hills transforming the Badlands. Around 500,000 years ago, glacial rivers flowed near the Badlands with the streams eroding rocks. Pinnacles and other formations began to evolve. Now there is constant erosion, and a million years from today, most of the soft rock will have eroded.

There are several dioramas. Jungle on a Seabed covers the shallow sea of the Cretaceous Period. It relates how a jungle sprang up 65 million years ago.

Winter Bison is a scene of bison and wolves. The wolves look like they are getting ready to attack.

Another depicts Death in Drying Grasslands. A hornless rhino in a muddy watering hole attracts an Archeotherium, a large piglike creature more closely related to a hippopotamus or whale. A composite of at least 17 different Archeotheriums was found at the Badlands’ Pig Dig. More than 19,000 specimens of various animals, but primarily rhinos and big pigs, have been recovered from the Pig Dig site during 15 years of excavation.

The diorama Dawn of the Prairie depicts that the land is drier now. A Nimravidae, a false saber toothed cat charges after a herd of Mesohippus, three-toed horses about the size of Collie dogs. They gallop away from the predator. Unconcerned by the commotion, a group of Leptomeryx (deer-like mammals the size of cats) feeds on shrubs and grasses as they move through the grasslands.

Another A Summer Afternoon Nearly Million 40 Years Ago takes place in an ancient forest. A titanothere grazes while alligators prowl and tortoises bask in the sun. A flock of oreodonts (sheep-like herbivores) keep an eye out for nearby predators. The oreodont has been the most common fossil found in the Badlands indicating they used to live in communities.

An interactive, Teeth Tell Tales, has visitors guess whether the teeth came from a carnivore or a herbivore. Examples are an alligator and an oreodont. Look for the Titanothere skull. Several of these species evolved in the Badlands over millions of years. They are distinguished by the size and shape of the protrusions on their skull. A full-grown Titanothere had a brain about the size of a human fist.

Prairie Wilderness describes the mixed grass prairie on the western edge of the park. The sign points out that a lot of the prairie has been lost due to land development and grazing of cattle and sheep. More panels cover those who passed through the area: French explorers, Lewis and Clark, and traders. Additional ones describe how hunters killed mammoths, the Lakota, the contest for the land, and homesteading. Look for the case of Lakota art and beaded items such as moccasins.

ENJOYING THE WILDLIFE

The Badlands are home to the largest mixed grass prairie in the National Park System. It is almost surrounded by Buffalo Gap National Grassland. A variety of wildlife roams this area. One can see bison, pronghorn, mule and whitetail deer, prairie dogs, coyotes, butterflies, turtles, and extensive bird species.

Roberts Prairie Dog Town is located five miles down from the Loop Road on Sage Creek Rim Road. Beware that this is a gravel road.

Named after a family that once homesteaded in the area, it is the largest accessible black-tailed prairie dog town in the park. It’s an ecology where you might see burrowing owls who use the burrows for their nests. Perhaps, you might see a hungry coyote, badger, hawk, or golden eagle looking for its dinner. Black-footed ferrets are nocturnal and can be seen around prairie dog towns at night. Prairie dogs comprise 90 percent of their diet.

We also saw American buffalo known as bison along Sage Road. At one time, 60 million bison roamed the territory. The American Indians depended upon all parts of the animal. With the coming of the railroad and the extent of homesteading, the animals were gone from this landscape by the 1880s. In 1963, they were reintroduced into the Sage Creek basin. Because of the fear of brucellosis, the animals are contained within 64,000 acres to keep them from mingling with cattle instead of being allowed to free-range. However, no bison has tested positive for brucellosis.

As you drive the Loop Road, you are likely to find bighorn sheep. The males have larger horns than the females. They enjoy the steep, rocky terrain because they are mountain climbers. The last known bighorn sheep was shot in the South Unit in 1926. They were reintroduced in 1964 in the Pinnacles and the Sheep Mountain areas. In 1996, they were relocated to the Cedar Pass area near the park headquarters.

If you pause between Big Foot and Dillon Passes, you may find pronghorn grazing in small bands on the open grasslands. This animal is smaller than a deer. It is named for the shape of its horns - one that ends in a short prong while the other is longer with a curved hook. It is the swiftest runner of all North American animals as it can reach speeds up to 55 mph.

A bird you are likely to see is the black-billed magpie which is often spotted around the park’s picnic sites and in front of the Ben Reifel Visitor Center. It is recognizable by its black and white coloring, iridescent green spread through its wings, and its long tail. When it flies, large white patches on its wing are visible.

Turkey vultures are often seen soaring around the Badland’s buttes. They’re about the size of an eagle but have a bald red head and a white bill. They are black or dark brown with white around the edges of their wings.

The Wall area is good for birding. You might spot black-capped chickadees and cedar waxwings. During the summer, cliff swallows migrate from their winter grounds in South America. Golden eagles and prairie falcons nest high on the cliffs and soar over the Badlands year round. Rock pigeons nest on pinnacles and ridges.

DINING AND SLEEPING

The Cedar Pass Lodge, the only lodging and restaurant in the park, is open from late April to the end of October. Hours vary so it is best to check out that information on the Cedar Pass Lodge web site. When you go for a meal, make sure they have your name on their list or the wait can be long. Lodging is at rustic cabins which book up fast so it is necessary to contact the lodge directly for reservations. Their telephone number is (877) 386-4383.

HIKING AND CAMPING

The primitive Sage Creek Campground is located in the North Unit off of the Sage Creek Rim Road. Though open year round, its sites temporarily close after winter storms and spring rains. It offers pit toilets, covered picnic tables, but no water. It is on a first come, first serve basis with a 14-day limit.

At the Cedar Pass Campground, camping costs $22 plus tax for two people, per night, with no hookups. If you want a site with electricity, the fee is $37 plus tax for two people per night. Winter camping fees are $15 plus tax. Ranger talks occur during the summer at the campground amphitheater. It contains cold running water, flush toilets, picnic tables, coin operated showers, and trash containers. A dump station is available for $1 per use. There are 96 sites. You can reserve on the Cedar Pass Lodge site.

Note: Campgrounds with hookups, though not part of the park, are located in Wall, South Dakota. That is where we stayed.

Hikes vary in length as well as requiring various degrees of fitness and experience. Check with the rangers at Ben Reifel Visitor Center to find which of the eight hikes are suitable for you.

The Fossil Exhibit Trail is a .25 miles long round trip and takes 20 minutes. This fully accessible trail features fossil exhibits.

The Window Trail is another easy .25 miles long round trip taking 20 minutes. It leads to a natural window in the Badlands Wall with a view of an eroded canyon.

The park recommends the following. Carry enough water, two quarts per person per each two-hour hike. Wear sturdy boots or shoes, a hat, and sunglasses. Keep a distance of at least 100 yards from all wildlife you encounter during your hike. Leave rocks, fossils, plants, and animals as you find them.

DETAILS:

The Badlands National Park address is 25216 Ben Reifel Road, Interior, South Dakota 57750. The telephone number is (605) 433-5361. The fee for a private vehicle (all occupants) is $20 for a week. Individuals hiking or biking are charged $10 for seven days while it is $10 for a motorcycle. Entry fees are collected year round. If stations are closed, fees can be paid at an automated fee station in the visitor center. National passes are accepted - senior, access, and military.

The park is open from noon to midnight daily. The Ben Reifel Visitor Center has winter and summer hours. Winter hours are 8:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. From mid-April to mid-May and early September to late October, the hours are 8:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Summer hours are 7:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m.

Badlands Entrance Sign and View of the Wall

Driving Along Loop Road

Another Drive Along Loop Road

A View of The Yellow Mounds

Hiking in the Yellow Mounds Area

A Close Up of the Yellow Mounds

Saddle Pass Trail

Big Badlands Overlook from a Distance

Big Badlands Overlook

A Panoramic View of the Badlands from Big Badlands Overlook

Big Badlands Overlook Looking Towards the Grasslands

White River Valley Overlook

Panorama Point Overlook

One of the Hikes Near Window Trail

The Ruggedness of Peaks

Panorama of the Badlands

Another View of the Badlands

RVers Love the Badlands - Cedar Pass Behind It

Badlands at Sunset - Conata Basin Overlook

The Wall Opposite the Ben Reifel Visitor Center

Ben Reifel Visitor Center

Brontothere Skull and Jaw

Archaeotherium

Paleontology Work

Modern and Fossil Tortoises

Winter Bison

Death in Drying Grasslands

Mesohippus

A Summer Afternoon Nearly 40 Million Years Ago

Roberts Prairie Dog Town

Prairie Dog Atop His Mound

Bighorn Sheep