Hello Everyone,

Located on the Oregon Coast between Bandon and Gold Beach, you’ll discover the small town of Port Orford. This fishing port and art community is the oldest town on the Oregon Coast and the most westerly in the 48 states.

A visit to this area provides opportunities to tour a lighthouse, a Victorian farmhouse, and a museum at a former lightboat station. You can also view the site where an Indian battle took place and learn about the location where the Japanese infiltrated our coast during World War II.

BATTLE ROCK

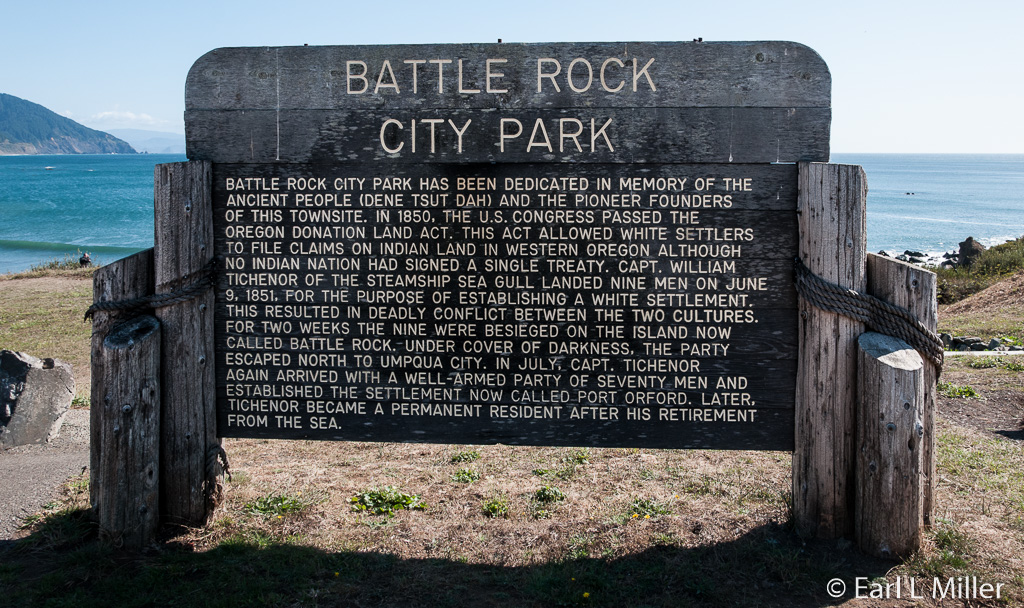

The Tutuni people, an Indian tribe, lived for thousands of years on the Oregon Coast. In 1850, the United States Congress passed the Oregon Donation Land Act. This act enabled white settlers to file claims on Indian land in Western Oregon despite no Indian nation having ever signed a treaty.

On June 9, 1851, Captain William Tichenor of the Steamship Sea Gull arrived from Portland. He left nine men to establish a European settlement with a promise to return in 14 days with men and supplies. The native Quatomah band felt the newcomers were encroaching on their land and reacted with hostilities.

The men, armed with three muskets, two rifles, one pistol, swords, and a signal cannon from the ship, made a rock, at the northern edge of the beach, their defensive camp. The native Indian tribe ordered the settlers off what they considered their beach. When the men didn’t comply, the settlers were attacked by more than 100 warriors. The settlers opened fire from the cannon and repulsed the attack which killed 23 natives and wounded two settlers.

A truce was called when the settlers agreed to leave after 14 days when the ship returned. However, Tichenor failed to show within two weeks as he had promised. His ship had been impounded in San Francisco due to debt.

For two weeks, the besieged settlers didn’t see any of the tribe. However, on the 15th day, an even larger band of Indians attacked. Reports have the number between 100 and 300. In the ensuing battle, the chief was killed. The Quatomahs retreated with their dead leader and set up camp nearby. The settlers fled north during the night, traveling more than a hundred miles, until they reached the Umpqua Valley.

In July 1851, Tichenor did return to the rock with a group of 70 soldiers to establish Port Orford. He became a permanent resident when he retired from the navy.

The rock today is known as Battle Rock at Battle Rock City Park. You can visit the park for outstanding Pacific Ocean views, read the plaque commemorating the activity at this site, and sometimes spot grey whales that congregate in the cove. You can also stop by the park’s visitor center from 9:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. daily to learn more about Port Orford. Directly below the park is a beach that’s good for exploring especially at a low tide.

During the 1850's, miners discovered gold in several places along the Rogue River and the coast. They failed to respect the native dwellings, fishing, or hunting sites. Mining also damaged the streams and fish run. Tensions rapidly increased with fighting started in several places along the Rogue, alternatively by the whites and the natives. In 1855-56, the Rogue River Indian War ended with the surrender of Chief John and his band, who were forced to move to the northern part of Oregon.

Port Orford became a port for mercantile trade and fishing. From here, logs and lumber were shipped to distant ports. Both the fishing and the timber industry declined after some very good years, and the port was sold to Gilbert Gable.

Gable was a leader in the State of Jefferson movement which had several southern Oregon and northern California counties forming a new state. When Gable died in December 1941, the plan died with him. The plan’s demise was assisted by the entrance of the United States into World War II.

CAPE BLANCO LIGHTHOUSE

Cape Blanco juts about 1-1/2 miles into the Pacific Ocean, terminating in a large headland with 200-foot cliffs. Spanish explorers named it because of the chalky white cliffs.

The area was extremely dangerous for shipping with many shipwrecks on rocks around Cape Blanco. Louis Knapp, owner of the town’s Knapp Hotel, was so concerned about the safety of mariners that he kept a lantern burning nightly in the hotel’s large window overlooking the sea. After the lighthouse was built, Knapp shut his lantern down.

In a 1869 report of the Lighthouse Board to Congress, it was stated that if brick could be made at the Cape, instead of brought from San Francisco, one third of the cost for transportation would be saved, and the lighthouse could be built. An agreement was made for someone to make the bricks and be paid $25 per thousand. Eighty thousand were made of fair quality and were accepted. The second batch of bricks weren’t of decent quality and were rejected.

The remainder of the supplies had to come via the ocean. When the first delivery arrived in May 1870, a gale occurred, when the vessel was partially unloaded, which caused a shipwreck and loss of the rest of the cargo. Eventually, the property obtained enough bricks. The circular tower rose to 50 feet and an oil room was attached to its base. A duplex, south of the tower, for the lightkeeper, his two assistants, and their families was constructed in 1870. A second home was completed in 1910.

The lighthouse’s fixed white light from a first-order Henry-Lepaute Fresnel lens was first lit on December 20, 1870. Its purposes were to warn ships away from the reefs which extended from the cape and provide a position fix for navigators. The light could be seen up to 23 miles at sea.

Originally lard-oil lamps were used inside the lens. In 1887, mineral-oil lamps replaced them. In 1890, a detached brick oil house was built to store the volatile fuel.

The station’s first lightkeeper was Harvey B. Burnap. However, the best known were James Langlois and James Hughes who spent their entire careers there, 42 years for Langlois and 37 years for Hughes. Most of this was spent with the men working together. Hughes was the second son of Patrick and Jane Hughes, whose 2,000-acre ranch bordered the lighthouse property. The ranch is located at Blanco State Park, and you can tour the Hughes home.

In 1903, Mabel Bretherton, Oregon’s first woman keeper, was appointed as second assistant at Cape Blanco. On the afternoon of October 19, 1903, in heavy seas and dense fog, the steamer South Portland, bound for San Francisco, struck a reef and sank within a half hour at Cape Blanco. Fourteen passengers, a 25 man crew, and a cargo of wheat were aboard. Captain McIntyre ordered the lifeboats lowered and made sure he was on the first one to leave. Eighteen people perished. McIntyre was found criminally negligent for leaving the ship too soon.

Around 1912, a hood was placed around the lamp inside the Fresnel lens. A clockwork mechanism raised and lowered it to produce a flashing signal - two second eclipse, three second light, two second eclipse, and thirteen second light. In 1925, a radio beacon was placed into commission to help mariners during periods of limited visibility.

The original lens was replaced in 1936 by a second-order revolving lens with eight bull’s-eyes. An electric motor, powered by a generator, rotated the lens. It produced a white flash that was on for 1.8 seconds and off for 18.2 seconds. The motor and lens still operate today.

Between 1967 and 1974, the two keepers’ dwellings were torn down. In March 1980, the station was automated and destaffed. It was off limits to visitors until it opened its doors on April 1, 1986. On April 21, 1993, it was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

The lighthouse is owned by the Coast Guard and managed by the Bureau of Land Management. It holds the record for the longest continuously operated lighthouse in Oregon. It is also the highest above the sea, the most westerly, and the most southern lighthouse in Oregon.

Full time RVers serve as docents at the lighthouse in exchange for a free campsite with hookups at Camp Blanco State Park. They lead visitors, along the 64 iron steps, to the top so they can examine the Fresnel lens up close. Tours are available from April through October, daily except Tuesday, from 10:00 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. Cost is $2 per adult for those ages 16 or older. It’s free for Federal Pass holders and for those under the age of 15. Lighthouse grounds are open only during tour hours.

You can pay for admission at the gift shop located on the park’s grounds. Be sure to take time to see the store's exhibits on the lighthouse’s history and Native Americans. It is located at 91100 Cape Blanco Road and the telephone number is (541) 332-2207.

HUGHES RANCH

While at Camp Blanco State Park, you can visit the Hughes Ranch, a 1898 Victorian farmhouse, built for pioneers Patrick and Jane Hughes. They lived there with their seven children. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places on November 28, 1980. Free tours are provided from 10:00 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. daily except Tuesdays, April through October.

The Hughes family came from Boston via San Francisco. Starting in 1860, Hughes eventually acquired a thousand acres around Cape Blanco which his sons expanded to 1,800 acres. They raised Holsteins and Jerseys. The family made butter which they shipped to San Francisco as well as provided milk for some of the area cheese. They lived in another home for almost four decades before building the residence you see on the property.

This Queen Anne/Eastlake style home is the only structure left of the ranch and dairy business operated by the Hughes. In 1981, great-grandson Patrick Masterson recalled also seeing a large washhouse and bunkhouse, a small chicken house, a slaughterhouse, a smokehouse, a creamery, and a dairy barn.

The 3,000 square foot, 11-room, two-story home is touted as the best preserved, largely unaltered, late nineteenth century house in the county. While the home always had running water, electricity was added in 1942.

As you approach the house, note an unusual exterior feature. John Lindberg, who built the house, abundantly used variously cut cedar shingles to shape patterns on the exterior walls. On the Hughes house, diamond-shaped patterns were used in the gables and semicircular fish scale and reverse fish scale patterns for the lower walls.

Guests entered the front hall and proceeded to the formal guest parlor decorated in shades of rose. The fireplace in this room reflects the Hughes’ wealth as it has a shallow firebox designed to burn coal rather than the cheaper wood.

It was primarily the men who gathered around the large table in the dining room. The women spent a lot of time in the spacious kitchen which was warmed by a cast iron, wood cook stove. It had a thermostat oven with eight different heat settings. Adjoining the kitchen and dining room is a large pass-thru-pantry with numerous storage bins.

As you visit the home, you’ll also see the men’s parlor and office. Here the men retired at day’s end to catch up on their bookwork and reading. The master bedroom, sewing room, and bath are also located on the first floor. Our docent pointed out that the master bedroom has some of the original wallpaper.

Upstairs, visitors find the other bedrooms and a chapel. John Hughes was a Roman Catholic priest serving a parish in Portland. The altar is original. Furniture throughout the home is period with the only personal belongings being family photos.

The last of the Hughes descendants occupied the ranch house until 1971 when it was acquired by the State of Oregon and incorporated into Cape Blanco State Park.

PORT ORFORD LIFEBOAT STATION

In 1934, a U.S. Coast Guard Lifeboat Station opened in Port Orford. It was constructed on a 280-foot high cliff above Nellie’s Cove and included a house for the officer-in-charge, barracks that also housed operations, a garage, a storage building, a pump house, and a lookout tower. By 1939, a two-bay boathouse and breakwater had been built at the cove. It was manned by an officer in charge and a crew of thirteen men and had two pulling boats (surf boats), and two motor lifeboats.

The “surfmen,” who operated the rescue boats, had to negotiate 532 wood and concrete steps to get from the station to the boathouse. To fuel the lifeboats, crewmen carried five-gallon cans down to the cove, one in each hand, until the tanks were full. In the winter, winds could whip up to 100 miles per hour. The men were responsible for 40 miles of coastline between Cape Blanco and Cape Sebastian.

The station’s crew handled three shipwrecks - in 1936, 1937, and 1941, without any loss of life. It became extremely busy during World War II as personnel increased from 13 to more than 100. Guardsmen patrolled the beaches with dogs. Near Port Orford, Japanese submarine I-25 launched a light aircraft to try and cause fires in the Oregon forests.

In 1970, the lifeboat station was decommissioned and then used by Oregon State University for marine research. Oregon State Parks acquired the station in 1976. The Port Orford Heritage Society worked with the parks department to restore and interpret the site in 1995.

In 1995, the station, with its five remaining buildings, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. These structures are the two-story crew quarters and office building, the officer-in-charge residence, garage, storage building, and pump house.

The boathouse burned down in the late 1970s. However, you can still see its pilings and breakwater structures. Portions of the rail-mounted carriage used to launch the boats into the cove are also visible.

The site opened its museum, formerly the two-story crew quarters and office building, to visitors in 2000. It has exhibits on both floors. The bottom floor has displays on the Japanese fire bombing of Oregon on September 9, 1942, information on various shipwrecks, ship models in one case, and photos of the lifeboat station and the men who worked here. In the “Lifeboat Room,” visitors find a Lyle gun that fired a rope to a boat in distress.

The “Shipwreck Room” contains artifacts from shipwrecks such as the port side running light from the S.S. Phyllis which wrecked in March of 1936. It also has part of the boiler system from the S.S. Willapa, whose 24-man crew was rescued by the station in 1941.

Visitors can view a Type 93 Model 1 Japanese mine detonator and harness from a mine that washed ashore at Nesika Beach, south of Port Orford, during World War II. The Type 93 Model 1 weighed 1,543 pounds and contained 220 pounds of Type 88 high explosives. Navy explosive ordnance disposal personnel detonated the mine, salvaging only those two parts.

The upstairs former crew bedrooms now are multipurpose. One serves as the museum staff’s office. At another, you can see short documentaries on maritime and Coast Guard subjects such as life at the station or oral histories of former Coast Guardsmen.

Three rooms have displays. One room concentrates on the town of Port Orford - its people and pioneers, a pharmacy collection, and the Cape Blanco Airport Diorama. During World War II, this was an auxiliary landing field. A second contains logging tools such as saws, pictures of the dock area, and newspaper articles about the dock. Another is laid out as a Coast Guard crew bedroom.

You can see the 36-foot self-righting motor lifeboat number 36498 on the grounds. Hikers can take the Tower Trail to the site where the observation tower used to be. It was removed in 1970 when the station was decommissioned.

You can also have a GI dog tag made on a vintage machine. Most people don’t know that the dog tag dates to the Civil War. During that war, 42 percent of the Civil War dead remained unidentified. Soldiers, on both sides, pinned a handkerchief or piece of paper with their names and addresses to their uniforms just before battle.

Harper’s Weekly Magazine advertised “Soldier’s Pins” which could be mail ordered made of silver or gold. These pins had inscribed the name and unit designation. Private vendors who followed the troops offered identification discs for sale just before battles.

U. S. Army Regulations in 1913 made identification tags mandatory and by 1917 American combat soldiers wore aluminum discs on chains around their necks. In the Navy, dog tags also go back to World War I.

You can visit this museum at Port Orford Heads State Park from 10:00 a.m. to 3:30 from April through October. It’s open every day but Tuesday. Admission is free. The phone number is (800) 551-6949.

JAPANESE SUBMARINE I-25

Fascinating exhibits at the museum inform visitors through photos and newspaper articles of two Japanese attacks on Oregon. These were the first attacks on the continental United States since the British invasion in 1814.

On September 9, 1942, the Imperial Japanese Navy submarine I-25, loaded with six bombs, surfaced west of Cape Blanco. It launched a small seaplane piloted by Chief Flying Officer Nobuo Fujita. Fujita flew southeast over the Oregon coast then dropped two incendiary bombs on the sides of Mount Emily, 10 miles northeast of Brookings. The rainy weather, which had delayed his mission for a few days, saturated the woods, and allowed the fire to be quickly extinguished.

After the bombing, a U.S. Army A-29 bomber spotted the submarine and attacked the submarine, forcing it to seek refuge on the ocean floor off of Port Orford. The A-29's attack inflicted only minor damage.

Fujita launched another sortie on September 29 using the Cape Blanco Lighthouse as a navigation beacon. After flying east for 90 minutes, Fujita dropped his bombs. He reported seeing flames, but the bombing remained unnoticed in the U.S.

The purpose of the bombings was to start a large forest fire that would weaken the war resolve of the United States and cause panic. The Japanese hoped it would cause the United States Navy to retreat from the Pacific to protect the West Coast.

The I-25 did not use its last two incendiary bombs. It reverted instead to torpedo attacks on American shipping, sinking the freighter SS Camden, the tanker SS Larry Doheny, and the Russian submarine L-16 which it mistook as American.

The I-25 was built by Mitsubishi in Kobe, Japan and was completed in October 1941. It was positioned off of Pearl Harbor during the attack on December 7 but damage to its aircraft prevented it from participating in scouting missions. It was one of seven Japanese submarines configured to carry a seaplane.

This submarine carried a crew of 97 men, including a pilot and crewman for the seaplane housed in a watertight hangar forward of the conning tower. A compressed-air catapult launched the reassembled plane. For its return, it taxied to the submarine and was hoisted aboard.

On September 3, 1943, U.S. Navy warships sank the I-25 approximately 150 miles northeast of Espiritu Santo. It is unknown which American ship sank the I-25 since three destroyers: USS Ellet, USS Patterson, and USS Taylor were involved in the naval engagement that day.

Fujita continued reconnaissance flying until 1944 when he returned to Japan to train Kamikaze pilots. He remains the only enemy pilot to drop bombs on the continental United States. After the war ended, Fujita opened a hardware store and later worked for a company that made wire.

In 1962, when he visited the city of Brookings, Fujita presented it with his family’s 400-year old samurai sword as a gesture of friendship. Fujita made three more trips to Brookings. He planted trees to mark the spot where he had dropped the bombs. He also donated more than a thousand dollars to the library to purchase books about Japan for children and hosted Brookings Harbor High School students at his home in Japan.

Fujita was an honored guest at the 1990 annual Azalea Festival in Brookings, and the city council declared him an honorary citizen. When he died in 1997, some of his ashes were scattered on Mount Emily.

Located on the Oregon Coast between Bandon and Gold Beach, you’ll discover the small town of Port Orford. This fishing port and art community is the oldest town on the Oregon Coast and the most westerly in the 48 states.

A visit to this area provides opportunities to tour a lighthouse, a Victorian farmhouse, and a museum at a former lightboat station. You can also view the site where an Indian battle took place and learn about the location where the Japanese infiltrated our coast during World War II.

BATTLE ROCK

The Tutuni people, an Indian tribe, lived for thousands of years on the Oregon Coast. In 1850, the United States Congress passed the Oregon Donation Land Act. This act enabled white settlers to file claims on Indian land in Western Oregon despite no Indian nation having ever signed a treaty.

On June 9, 1851, Captain William Tichenor of the Steamship Sea Gull arrived from Portland. He left nine men to establish a European settlement with a promise to return in 14 days with men and supplies. The native Quatomah band felt the newcomers were encroaching on their land and reacted with hostilities.

The men, armed with three muskets, two rifles, one pistol, swords, and a signal cannon from the ship, made a rock, at the northern edge of the beach, their defensive camp. The native Indian tribe ordered the settlers off what they considered their beach. When the men didn’t comply, the settlers were attacked by more than 100 warriors. The settlers opened fire from the cannon and repulsed the attack which killed 23 natives and wounded two settlers.

A truce was called when the settlers agreed to leave after 14 days when the ship returned. However, Tichenor failed to show within two weeks as he had promised. His ship had been impounded in San Francisco due to debt.

For two weeks, the besieged settlers didn’t see any of the tribe. However, on the 15th day, an even larger band of Indians attacked. Reports have the number between 100 and 300. In the ensuing battle, the chief was killed. The Quatomahs retreated with their dead leader and set up camp nearby. The settlers fled north during the night, traveling more than a hundred miles, until they reached the Umpqua Valley.

In July 1851, Tichenor did return to the rock with a group of 70 soldiers to establish Port Orford. He became a permanent resident when he retired from the navy.

The rock today is known as Battle Rock at Battle Rock City Park. You can visit the park for outstanding Pacific Ocean views, read the plaque commemorating the activity at this site, and sometimes spot grey whales that congregate in the cove. You can also stop by the park’s visitor center from 9:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. daily to learn more about Port Orford. Directly below the park is a beach that’s good for exploring especially at a low tide.

During the 1850's, miners discovered gold in several places along the Rogue River and the coast. They failed to respect the native dwellings, fishing, or hunting sites. Mining also damaged the streams and fish run. Tensions rapidly increased with fighting started in several places along the Rogue, alternatively by the whites and the natives. In 1855-56, the Rogue River Indian War ended with the surrender of Chief John and his band, who were forced to move to the northern part of Oregon.

Port Orford became a port for mercantile trade and fishing. From here, logs and lumber were shipped to distant ports. Both the fishing and the timber industry declined after some very good years, and the port was sold to Gilbert Gable.

Gable was a leader in the State of Jefferson movement which had several southern Oregon and northern California counties forming a new state. When Gable died in December 1941, the plan died with him. The plan’s demise was assisted by the entrance of the United States into World War II.

CAPE BLANCO LIGHTHOUSE

Cape Blanco juts about 1-1/2 miles into the Pacific Ocean, terminating in a large headland with 200-foot cliffs. Spanish explorers named it because of the chalky white cliffs.

The area was extremely dangerous for shipping with many shipwrecks on rocks around Cape Blanco. Louis Knapp, owner of the town’s Knapp Hotel, was so concerned about the safety of mariners that he kept a lantern burning nightly in the hotel’s large window overlooking the sea. After the lighthouse was built, Knapp shut his lantern down.

In a 1869 report of the Lighthouse Board to Congress, it was stated that if brick could be made at the Cape, instead of brought from San Francisco, one third of the cost for transportation would be saved, and the lighthouse could be built. An agreement was made for someone to make the bricks and be paid $25 per thousand. Eighty thousand were made of fair quality and were accepted. The second batch of bricks weren’t of decent quality and were rejected.

The remainder of the supplies had to come via the ocean. When the first delivery arrived in May 1870, a gale occurred, when the vessel was partially unloaded, which caused a shipwreck and loss of the rest of the cargo. Eventually, the property obtained enough bricks. The circular tower rose to 50 feet and an oil room was attached to its base. A duplex, south of the tower, for the lightkeeper, his two assistants, and their families was constructed in 1870. A second home was completed in 1910.

The lighthouse’s fixed white light from a first-order Henry-Lepaute Fresnel lens was first lit on December 20, 1870. Its purposes were to warn ships away from the reefs which extended from the cape and provide a position fix for navigators. The light could be seen up to 23 miles at sea.

Originally lard-oil lamps were used inside the lens. In 1887, mineral-oil lamps replaced them. In 1890, a detached brick oil house was built to store the volatile fuel.

The station’s first lightkeeper was Harvey B. Burnap. However, the best known were James Langlois and James Hughes who spent their entire careers there, 42 years for Langlois and 37 years for Hughes. Most of this was spent with the men working together. Hughes was the second son of Patrick and Jane Hughes, whose 2,000-acre ranch bordered the lighthouse property. The ranch is located at Blanco State Park, and you can tour the Hughes home.

In 1903, Mabel Bretherton, Oregon’s first woman keeper, was appointed as second assistant at Cape Blanco. On the afternoon of October 19, 1903, in heavy seas and dense fog, the steamer South Portland, bound for San Francisco, struck a reef and sank within a half hour at Cape Blanco. Fourteen passengers, a 25 man crew, and a cargo of wheat were aboard. Captain McIntyre ordered the lifeboats lowered and made sure he was on the first one to leave. Eighteen people perished. McIntyre was found criminally negligent for leaving the ship too soon.

Around 1912, a hood was placed around the lamp inside the Fresnel lens. A clockwork mechanism raised and lowered it to produce a flashing signal - two second eclipse, three second light, two second eclipse, and thirteen second light. In 1925, a radio beacon was placed into commission to help mariners during periods of limited visibility.

The original lens was replaced in 1936 by a second-order revolving lens with eight bull’s-eyes. An electric motor, powered by a generator, rotated the lens. It produced a white flash that was on for 1.8 seconds and off for 18.2 seconds. The motor and lens still operate today.

Between 1967 and 1974, the two keepers’ dwellings were torn down. In March 1980, the station was automated and destaffed. It was off limits to visitors until it opened its doors on April 1, 1986. On April 21, 1993, it was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

The lighthouse is owned by the Coast Guard and managed by the Bureau of Land Management. It holds the record for the longest continuously operated lighthouse in Oregon. It is also the highest above the sea, the most westerly, and the most southern lighthouse in Oregon.

Full time RVers serve as docents at the lighthouse in exchange for a free campsite with hookups at Camp Blanco State Park. They lead visitors, along the 64 iron steps, to the top so they can examine the Fresnel lens up close. Tours are available from April through October, daily except Tuesday, from 10:00 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. Cost is $2 per adult for those ages 16 or older. It’s free for Federal Pass holders and for those under the age of 15. Lighthouse grounds are open only during tour hours.

You can pay for admission at the gift shop located on the park’s grounds. Be sure to take time to see the store's exhibits on the lighthouse’s history and Native Americans. It is located at 91100 Cape Blanco Road and the telephone number is (541) 332-2207.

HUGHES RANCH

While at Camp Blanco State Park, you can visit the Hughes Ranch, a 1898 Victorian farmhouse, built for pioneers Patrick and Jane Hughes. They lived there with their seven children. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places on November 28, 1980. Free tours are provided from 10:00 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. daily except Tuesdays, April through October.

The Hughes family came from Boston via San Francisco. Starting in 1860, Hughes eventually acquired a thousand acres around Cape Blanco which his sons expanded to 1,800 acres. They raised Holsteins and Jerseys. The family made butter which they shipped to San Francisco as well as provided milk for some of the area cheese. They lived in another home for almost four decades before building the residence you see on the property.

This Queen Anne/Eastlake style home is the only structure left of the ranch and dairy business operated by the Hughes. In 1981, great-grandson Patrick Masterson recalled also seeing a large washhouse and bunkhouse, a small chicken house, a slaughterhouse, a smokehouse, a creamery, and a dairy barn.

The 3,000 square foot, 11-room, two-story home is touted as the best preserved, largely unaltered, late nineteenth century house in the county. While the home always had running water, electricity was added in 1942.

As you approach the house, note an unusual exterior feature. John Lindberg, who built the house, abundantly used variously cut cedar shingles to shape patterns on the exterior walls. On the Hughes house, diamond-shaped patterns were used in the gables and semicircular fish scale and reverse fish scale patterns for the lower walls.

Guests entered the front hall and proceeded to the formal guest parlor decorated in shades of rose. The fireplace in this room reflects the Hughes’ wealth as it has a shallow firebox designed to burn coal rather than the cheaper wood.

It was primarily the men who gathered around the large table in the dining room. The women spent a lot of time in the spacious kitchen which was warmed by a cast iron, wood cook stove. It had a thermostat oven with eight different heat settings. Adjoining the kitchen and dining room is a large pass-thru-pantry with numerous storage bins.

As you visit the home, you’ll also see the men’s parlor and office. Here the men retired at day’s end to catch up on their bookwork and reading. The master bedroom, sewing room, and bath are also located on the first floor. Our docent pointed out that the master bedroom has some of the original wallpaper.

Upstairs, visitors find the other bedrooms and a chapel. John Hughes was a Roman Catholic priest serving a parish in Portland. The altar is original. Furniture throughout the home is period with the only personal belongings being family photos.

The last of the Hughes descendants occupied the ranch house until 1971 when it was acquired by the State of Oregon and incorporated into Cape Blanco State Park.

PORT ORFORD LIFEBOAT STATION

In 1934, a U.S. Coast Guard Lifeboat Station opened in Port Orford. It was constructed on a 280-foot high cliff above Nellie’s Cove and included a house for the officer-in-charge, barracks that also housed operations, a garage, a storage building, a pump house, and a lookout tower. By 1939, a two-bay boathouse and breakwater had been built at the cove. It was manned by an officer in charge and a crew of thirteen men and had two pulling boats (surf boats), and two motor lifeboats.

The “surfmen,” who operated the rescue boats, had to negotiate 532 wood and concrete steps to get from the station to the boathouse. To fuel the lifeboats, crewmen carried five-gallon cans down to the cove, one in each hand, until the tanks were full. In the winter, winds could whip up to 100 miles per hour. The men were responsible for 40 miles of coastline between Cape Blanco and Cape Sebastian.

The station’s crew handled three shipwrecks - in 1936, 1937, and 1941, without any loss of life. It became extremely busy during World War II as personnel increased from 13 to more than 100. Guardsmen patrolled the beaches with dogs. Near Port Orford, Japanese submarine I-25 launched a light aircraft to try and cause fires in the Oregon forests.

In 1970, the lifeboat station was decommissioned and then used by Oregon State University for marine research. Oregon State Parks acquired the station in 1976. The Port Orford Heritage Society worked with the parks department to restore and interpret the site in 1995.

In 1995, the station, with its five remaining buildings, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. These structures are the two-story crew quarters and office building, the officer-in-charge residence, garage, storage building, and pump house.

The boathouse burned down in the late 1970s. However, you can still see its pilings and breakwater structures. Portions of the rail-mounted carriage used to launch the boats into the cove are also visible.

The site opened its museum, formerly the two-story crew quarters and office building, to visitors in 2000. It has exhibits on both floors. The bottom floor has displays on the Japanese fire bombing of Oregon on September 9, 1942, information on various shipwrecks, ship models in one case, and photos of the lifeboat station and the men who worked here. In the “Lifeboat Room,” visitors find a Lyle gun that fired a rope to a boat in distress.

The “Shipwreck Room” contains artifacts from shipwrecks such as the port side running light from the S.S. Phyllis which wrecked in March of 1936. It also has part of the boiler system from the S.S. Willapa, whose 24-man crew was rescued by the station in 1941.

Visitors can view a Type 93 Model 1 Japanese mine detonator and harness from a mine that washed ashore at Nesika Beach, south of Port Orford, during World War II. The Type 93 Model 1 weighed 1,543 pounds and contained 220 pounds of Type 88 high explosives. Navy explosive ordnance disposal personnel detonated the mine, salvaging only those two parts.

The upstairs former crew bedrooms now are multipurpose. One serves as the museum staff’s office. At another, you can see short documentaries on maritime and Coast Guard subjects such as life at the station or oral histories of former Coast Guardsmen.

Three rooms have displays. One room concentrates on the town of Port Orford - its people and pioneers, a pharmacy collection, and the Cape Blanco Airport Diorama. During World War II, this was an auxiliary landing field. A second contains logging tools such as saws, pictures of the dock area, and newspaper articles about the dock. Another is laid out as a Coast Guard crew bedroom.

You can see the 36-foot self-righting motor lifeboat number 36498 on the grounds. Hikers can take the Tower Trail to the site where the observation tower used to be. It was removed in 1970 when the station was decommissioned.

You can also have a GI dog tag made on a vintage machine. Most people don’t know that the dog tag dates to the Civil War. During that war, 42 percent of the Civil War dead remained unidentified. Soldiers, on both sides, pinned a handkerchief or piece of paper with their names and addresses to their uniforms just before battle.

Harper’s Weekly Magazine advertised “Soldier’s Pins” which could be mail ordered made of silver or gold. These pins had inscribed the name and unit designation. Private vendors who followed the troops offered identification discs for sale just before battles.

U. S. Army Regulations in 1913 made identification tags mandatory and by 1917 American combat soldiers wore aluminum discs on chains around their necks. In the Navy, dog tags also go back to World War I.

You can visit this museum at Port Orford Heads State Park from 10:00 a.m. to 3:30 from April through October. It’s open every day but Tuesday. Admission is free. The phone number is (800) 551-6949.

JAPANESE SUBMARINE I-25

Fascinating exhibits at the museum inform visitors through photos and newspaper articles of two Japanese attacks on Oregon. These were the first attacks on the continental United States since the British invasion in 1814.

On September 9, 1942, the Imperial Japanese Navy submarine I-25, loaded with six bombs, surfaced west of Cape Blanco. It launched a small seaplane piloted by Chief Flying Officer Nobuo Fujita. Fujita flew southeast over the Oregon coast then dropped two incendiary bombs on the sides of Mount Emily, 10 miles northeast of Brookings. The rainy weather, which had delayed his mission for a few days, saturated the woods, and allowed the fire to be quickly extinguished.

After the bombing, a U.S. Army A-29 bomber spotted the submarine and attacked the submarine, forcing it to seek refuge on the ocean floor off of Port Orford. The A-29's attack inflicted only minor damage.

Fujita launched another sortie on September 29 using the Cape Blanco Lighthouse as a navigation beacon. After flying east for 90 minutes, Fujita dropped his bombs. He reported seeing flames, but the bombing remained unnoticed in the U.S.

The purpose of the bombings was to start a large forest fire that would weaken the war resolve of the United States and cause panic. The Japanese hoped it would cause the United States Navy to retreat from the Pacific to protect the West Coast.

The I-25 did not use its last two incendiary bombs. It reverted instead to torpedo attacks on American shipping, sinking the freighter SS Camden, the tanker SS Larry Doheny, and the Russian submarine L-16 which it mistook as American.

The I-25 was built by Mitsubishi in Kobe, Japan and was completed in October 1941. It was positioned off of Pearl Harbor during the attack on December 7 but damage to its aircraft prevented it from participating in scouting missions. It was one of seven Japanese submarines configured to carry a seaplane.

This submarine carried a crew of 97 men, including a pilot and crewman for the seaplane housed in a watertight hangar forward of the conning tower. A compressed-air catapult launched the reassembled plane. For its return, it taxied to the submarine and was hoisted aboard.

On September 3, 1943, U.S. Navy warships sank the I-25 approximately 150 miles northeast of Espiritu Santo. It is unknown which American ship sank the I-25 since three destroyers: USS Ellet, USS Patterson, and USS Taylor were involved in the naval engagement that day.

Fujita continued reconnaissance flying until 1944 when he returned to Japan to train Kamikaze pilots. He remains the only enemy pilot to drop bombs on the continental United States. After the war ended, Fujita opened a hardware store and later worked for a company that made wire.

In 1962, when he visited the city of Brookings, Fujita presented it with his family’s 400-year old samurai sword as a gesture of friendship. Fujita made three more trips to Brookings. He planted trees to mark the spot where he had dropped the bombs. He also donated more than a thousand dollars to the library to purchase books about Japan for children and hosted Brookings Harbor High School students at his home in Japan.

Fujita was an honored guest at the 1990 annual Azalea Festival in Brookings, and the city council declared him an honorary citizen. When he died in 1997, some of his ashes were scattered on Mount Emily.

Sign about the Indian battle at Battle Rock

View from Battle Rock City Park

Cape Blanco Lighthouse

Interior of Cape Blanco Lighthouse

Stairway to Top of Cape Blanco Lighthouse

View from Cape Blanco Lighthouse

Hughes Ranch House

Formal Guest Parlor of Hughes Home

Kitchen of Hughes Home

Port Orford Lifeboat Station Museum

Detonator and Harness from Type 93 Model 1 Japanese Mine

Model of I-25 submarine

Layout of Crew Bedroom

Officer-in-Charge Residence

Self-Righting Motor Lifeboat Number 36498