Hello Everyone,

Willamette Heritage Center preserves and interprets the history of the Mid-Willamette Valley through the fourteen buildings on their site. Structures dating from 1841 to 1858 consist of the Jason Lee House, Parsonage, John Boon Home and Pleasant Grove Church. . The Thomas Kay Woolen Mill and its out buildings operated between 1889 and 1962. The National Park Service named the Mill an American Treasure.

It is possible to tour the facility by yourself by obtaining a key and museum guide where you pay your admission fee. However, the best way to see it is with a docent as they provide additional insight into what you are viewing. You will find docents for the mill on Tuesdays through Saturdays and for the Methodist Mission buildings on Wednesdays, Thursdays, and Fridays. In any case, start with viewing the 12-minute video which provides an overall understanding of the Center.

You may spot some living history on the grounds when you visit. It’s the Center’s Teenage Interpretative Program (TIP). Youngsters, ages 14-18, dress in costume and research the roles they play. When we were there, a few young women were demonstrating hand sewing.

METHODIST MISSION TO OREGON

Because of contact with Lewis and Clark, as well as other explorers and traders, the Nez Perce sent four representatives to St. Louis to seek out General William Clark. Their purpose was to learn about the white man’s religion. This was interpreted by the Methodist press in New England as a “Macedonian Cry.”

On June 14, 1833, Jason Lee, a Boston Methodist minister and teacher, was ordained by Bishop Elijah Heading as “Missionary to the Flathead Indians.” Four men accompanied Lee in the company of Captain Nathaniel Wyeth to establish the mission. They arrived at Fort Vancouver on September 15, 1834 and were advised by Hudson Bay’s Chief Factor, John McLoughlin, to settle the mission in the Willamette Valley. There they would find fertile land and the Kalapuya, who had been congenial to traders.

The mission was established at Mission Bottom. Its purpose was to convert the native population to Christianity, provide an education, and teach agriculture. However, problems with flooding and mosquitos were common. After the Great Reinforcement, the third supplemental group of missionaries arrived on the ship Lausanne in 1840, the group moved to Chemeketa Plain. The location later became Salem.

Equipment for the first saw and grist mills arrived on the ship. Homes were established, and the mission eventually grew to include five satellite stations including Tacoma, Washington and Oregon City and The Dalles, Oregon.

Yet, it did not meet with much success. The Kalapuya population, between 1829 and 1833, decreased 90% due to such illnesses as tuberculosis and malaria which they had caught from settlers and traders. Participants averaged only 20 to 40, and 99 percent returned to their old religion. By 1844, the Methodist Mission to Oregon was effectively closed.

JASON LEE HOUSE

This was the first frame structure built in 1841. Four missionary families originally occupied the home with each family having its own apartment. It served a variety of purposes including being headquarters for Methodist Mission operations. It also hosted the early provisional government meetings and served as the second post office and second grocery store. Since there were no banks, bartering was the method of exchange. It was moved to the site in 1965 from its original location north of downtown Salem.

An interesting architectural element was that there were no stairs to the second floor until 1852. A ladder had to be used to enter and exit that level.

Exhibits cover the History of the Methodist Mission to Oregon, Missionaries and Their Family, and Early Education in Oregon Country. You’ll see wallboards in the hall on The Great Reinforcement and the others that followed, their overland journey, and the residents of the Lee House.

In the second room are several notable artifacts. These include Jason Lee’s writing desk and Bible, a high chair built on the ship, and a chair assembled on board the Lausanne. This is the room in which the Lee family lived.

In the last room, you’ll see Kalapuya baskets and ferrier, blacksmith, and shoemaker tools. You’ll also spot other Kalapua artifacts - beaded objects and moccasins. It’s the room to learn about the Indian schools.

Education was a major calling for many of the missionaries. They established the Oregon Institute for the children of Western settlers. When the mission closed, the Indian Manual Training School building was purchased for the Institute which later became Willamette University.

THE PARSONAGE

The Methodist Parsonage, the second frame structure constructed in 1841, housed people who were related to the Indian Manual Training School. It’s believed those classes were held here while the school building was constructed. This was the only building retained by the Methodist Church after the mission was closed. It then served as a parsonage for their minister and as a base for circuit riders, itinerant preachers who served those living in lightly populated towns. It was originally located where the mill’s water tower now stands.

A roomful of displays is on the Kalapuya’s history. The Kalapuyas were friendly with the settlers who were hungry for land. The treaties of the 1850's forced separate tribes to confederate and move to a certain location. Most of the Kalapuya moved to the Grand Ronde Reservation along with various other Oregon bands where they remained from 1856 to 1954. In 1954, a trust relationship between the federal government and the Tribes of Western Oregon left the Grand Ronde people landless for 30 years. In 1983, Congress restored the trust relationship and recognized the Grand Ronde tribe as a sovereign nation. With the reestablishment of the reservation, the Tribe now works to build a self-sufficient community.

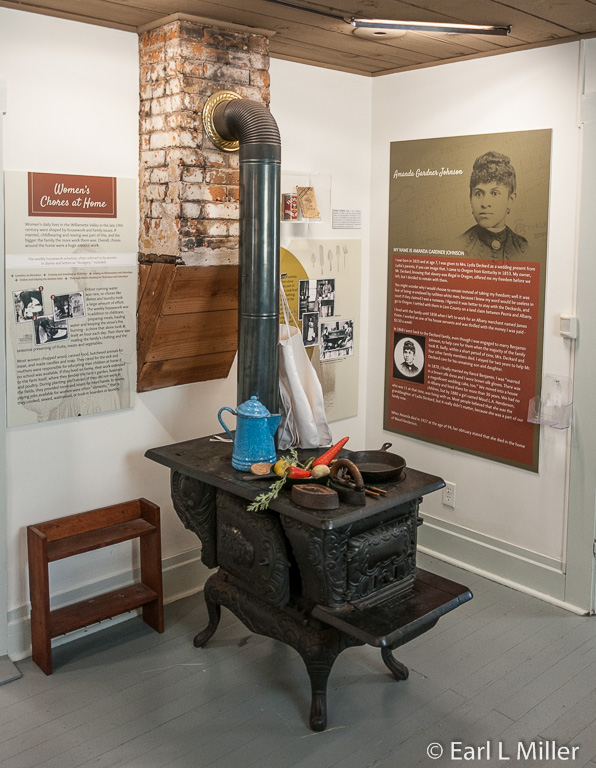

Other exhibits are on Women and Children, Families, and Historic Preservation. You’ll see toys and school desks, an old-fashioned stove and dry sink, and an iron that worked without electricity. You’ll see wallboards on such topics as chores at home, childbirth, and women outside the home.

THE BOON HOUSE

John Boon, a Wesleyan Methodist minister, born in Athens, Ohio, came over the Oregon Trail in 1845. He was involved in several business ventures. Boon was one of 27 organizers of the Pacific Telegraph Company linking Portland to Corvallis. It was Oregon’s first telegraph line. He was also commissioner of the California Railroad Company that incorporated in 1854. Active in politics, he was the last Territorial and first State Treasurer in Oregon.

As a backer for the Willamette Woolen Manufacturing Company, he pushed for the development of the Salem Ditch. It connected Mill Creek to the Santiam River, assuring a strong water supply to power Salem’s various industries. The same mill race that powered the Thomas Kay Woolen Mill is fed by Mill Creek.

This home is the oldest single family house still standing in Salem. It was originally located next to the building known as Boon’s Treasury, built by Boon and his son, and served as Oregon’s first State Treasury.

Exhibits in this house are on The Boon Family, The Oregon Trail, and Early Industry and Agriculture. The Oregon Trail displays cover the idea that people who came to Oregon were from such countries as Germany, Switzerland, and Russia. They were a very diverse group. The exhibit also discusses the idea of Manifest Destiny and the perils of the Oregon Trail such as terrain, accident, and disease.

Early Industry and Agriculture concentrate on the fact that the Willamette Valley became known as an agricultural hub rich with orchards and farms. Marionberries were developed in Marion County and named for the county. The county was named for Francis Marion, an American Revolutionary War military officer.

PLEASANT GROVE PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH

This church dates to 1858. It was called the “Condit Church” for its founding minister, Reverend Phillip Condit, who arrived with his family from Pennsylvania in 1854. Built as a community effort, its doors, windows, sashes, pews, and a pulpit were all handmade by volunteers. Unfortunately, Condit didn’t live to see his church completed.

Representing a meetinghouse-style associated with early country churches, it’s the oldest surviving Presbyterian Church in the Pacific Northwest. It was moved from near Aumsville, 15 miles away, to the Center’s grounds in 1984 and is currently rented out for special events.

THOMAS KAY WOOLEN MILL

During the late 1800's, the Salem area was a vast wool processing area because of the abundance of water and sheep. The mill received strong financial support when it was established in 1889. In just three weeks, the business community raised $20,000 to help secure the mill for Salem. It employed one out of every five non farming workers.

In December 1895, a fire burned the main building to the ground. Within six months, due to community support, it was in operation again. It ran continuously even through the Depression and a strike in 1934. During World War I, World War II, and the Korean War, productivity increased when it supplied blankets and uniforms to the U.S. Army. It closed in 1962 primarily because of competition from synthetic materials such as polyester and because the machines didn’t get upgraded.

The mill was founded by Thomas Lister Kay, who was an immigrant from England, and his wife. He apprenticed in England then worked for Brownsville Woolen Mill, Oregon’s second woolen mill. After becoming a partner in that mill, he sold his interest and started his own company. Three generations of Kays ran it after him.

His daughter, Martha Ann, better known as Fannie, worked at the Brownsville Mill with her father then at his mill. When Thomas Kay Woolen Mill was turned over to her brother, Thomas Benjamin Kay, she and her husband, Charles Bishop, purchased the bankrupt Pendleton Woolen Mill in 1909. It was later managed by their sons, Clarence and Roy. The Bishop family still operates Pendleton today.

TOUR OF THE MILL

By touring the mill, you will learn that the manufacture of woolen products such as blankets, for which it was known, was a complex process involving a number of steps. It wasn’t just spinning and weaving. You’ll also learn it was water power in action as the mill did not use electricity in processing until 1941. The water fell at this mill 12 feet to turn the two turbines, including the one main one.

Your first stop is the Mentzer Machine Shop named for millwright Wayne Mentzer, who served this occupation for sixty years. His work took place in that shop. The moving machinery and tools on display are original to the mill. They were used for everything from making machine parts to repairing structures.

Walk down the stairs and through the shelter and you’ll pass the crown gears. These transferred motion from the vertical turbine to the horizontal shaft that powered all of the main building’s machinery.

Next is the picker building where fleece was picked clean of burrs, grass, feces, and pests. Another type of picking took place as well. Snaps and zippers were cut off then other machines picked wool products to recycle their fibers. This was made into less expensive “shoddy” wool.

During the mill’s operation, dyeing was done in a series of interconnected sheds and buildings. These are gone today, and the dyeing process is portrayed in a mural on the mill building’s south wall. It sometimes took three hours to get the right color. The color went into the mill race.

You will reach the mill building after going through the scouring building which housed machines to scour the dirty wool. The process was very slow because wool becomes felt if agitated too much.

Whether you go with a guide or by yourself, the mill building covers the steps from carding to pressing and final inspection. Each of the steps has wallboards which explain what you will be seeing.

The Weaver’s Guild meets on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Fridays. Take the elevator to the fourth floor to watch them in action. Then take an elevator to the second floor to see carding, spinning, dressing (setting up the loom), weaving, and perching in that order. This is where we found going with a guide was useful since she explained each of the processes and demonstrated parts of the loom.

We learned after weaving, that the fabric was hung on a “perch” for inspection. After imperfections were marked, the cloth was cut and dropped through a trap door. It was then weighed, measured, ticketed, and passed to the burlers and finishers in the mending room below.

The rest of the procedure was done downstairs. The burler’s job was to find and remove knots, bunches, and loose ends. He then marked any “runs” to which menders added needed fabric. The menders rewove the fabric by hand when threads were missing.

At the fulling mills, they used warm water and soap to conduct a controlled shrink so that the material came together. The fabric was washed of all soap and dirt after fulling. Then an extractor, by spinning, squeezed excess water out of the fabric. During the early days, the fabric was stretched out on long racks called “tenterhooks” on the fourth floor. In 1941, a machine dryer was used in a shed attached to the first floor.

Nap or pile on the fabric was raised by using nappers with wire-covered rollers. These replaced the teasels with 2,500 to 4,000 heads that lasted six hours. We learned from our guide that New York and Oregon are the largest two teasel states in the nation. Then the pile was trimmed with a shearing machine.

A steam press smoothed the fabric giving it a finished look. An inspector looked for any final imperfections. Then the blankets were bound, folded, rolled, weighed, and labeled. Orders were readied for shipping.

DETAILS

The Willamette Heritage Center is located at 1313 Mill Street SE in Salem. Its phone number is (503) 585-7012. Hours are Monday through Saturday 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Access to the grounds is free. Visiting the museum is $7.00 Adults, $6.00 Seniors (65 +), $4.00 Students (with ID), $3.00 Youth (6 - 17) and children under age five free.

Willamette Heritage Center preserves and interprets the history of the Mid-Willamette Valley through the fourteen buildings on their site. Structures dating from 1841 to 1858 consist of the Jason Lee House, Parsonage, John Boon Home and Pleasant Grove Church. . The Thomas Kay Woolen Mill and its out buildings operated between 1889 and 1962. The National Park Service named the Mill an American Treasure.

It is possible to tour the facility by yourself by obtaining a key and museum guide where you pay your admission fee. However, the best way to see it is with a docent as they provide additional insight into what you are viewing. You will find docents for the mill on Tuesdays through Saturdays and for the Methodist Mission buildings on Wednesdays, Thursdays, and Fridays. In any case, start with viewing the 12-minute video which provides an overall understanding of the Center.

You may spot some living history on the grounds when you visit. It’s the Center’s Teenage Interpretative Program (TIP). Youngsters, ages 14-18, dress in costume and research the roles they play. When we were there, a few young women were demonstrating hand sewing.

METHODIST MISSION TO OREGON

Because of contact with Lewis and Clark, as well as other explorers and traders, the Nez Perce sent four representatives to St. Louis to seek out General William Clark. Their purpose was to learn about the white man’s religion. This was interpreted by the Methodist press in New England as a “Macedonian Cry.”

On June 14, 1833, Jason Lee, a Boston Methodist minister and teacher, was ordained by Bishop Elijah Heading as “Missionary to the Flathead Indians.” Four men accompanied Lee in the company of Captain Nathaniel Wyeth to establish the mission. They arrived at Fort Vancouver on September 15, 1834 and were advised by Hudson Bay’s Chief Factor, John McLoughlin, to settle the mission in the Willamette Valley. There they would find fertile land and the Kalapuya, who had been congenial to traders.

The mission was established at Mission Bottom. Its purpose was to convert the native population to Christianity, provide an education, and teach agriculture. However, problems with flooding and mosquitos were common. After the Great Reinforcement, the third supplemental group of missionaries arrived on the ship Lausanne in 1840, the group moved to Chemeketa Plain. The location later became Salem.

Equipment for the first saw and grist mills arrived on the ship. Homes were established, and the mission eventually grew to include five satellite stations including Tacoma, Washington and Oregon City and The Dalles, Oregon.

Yet, it did not meet with much success. The Kalapuya population, between 1829 and 1833, decreased 90% due to such illnesses as tuberculosis and malaria which they had caught from settlers and traders. Participants averaged only 20 to 40, and 99 percent returned to their old religion. By 1844, the Methodist Mission to Oregon was effectively closed.

JASON LEE HOUSE

This was the first frame structure built in 1841. Four missionary families originally occupied the home with each family having its own apartment. It served a variety of purposes including being headquarters for Methodist Mission operations. It also hosted the early provisional government meetings and served as the second post office and second grocery store. Since there were no banks, bartering was the method of exchange. It was moved to the site in 1965 from its original location north of downtown Salem.

An interesting architectural element was that there were no stairs to the second floor until 1852. A ladder had to be used to enter and exit that level.

Exhibits cover the History of the Methodist Mission to Oregon, Missionaries and Their Family, and Early Education in Oregon Country. You’ll see wallboards in the hall on The Great Reinforcement and the others that followed, their overland journey, and the residents of the Lee House.

In the second room are several notable artifacts. These include Jason Lee’s writing desk and Bible, a high chair built on the ship, and a chair assembled on board the Lausanne. This is the room in which the Lee family lived.

In the last room, you’ll see Kalapuya baskets and ferrier, blacksmith, and shoemaker tools. You’ll also spot other Kalapua artifacts - beaded objects and moccasins. It’s the room to learn about the Indian schools.

Education was a major calling for many of the missionaries. They established the Oregon Institute for the children of Western settlers. When the mission closed, the Indian Manual Training School building was purchased for the Institute which later became Willamette University.

THE PARSONAGE

The Methodist Parsonage, the second frame structure constructed in 1841, housed people who were related to the Indian Manual Training School. It’s believed those classes were held here while the school building was constructed. This was the only building retained by the Methodist Church after the mission was closed. It then served as a parsonage for their minister and as a base for circuit riders, itinerant preachers who served those living in lightly populated towns. It was originally located where the mill’s water tower now stands.

A roomful of displays is on the Kalapuya’s history. The Kalapuyas were friendly with the settlers who were hungry for land. The treaties of the 1850's forced separate tribes to confederate and move to a certain location. Most of the Kalapuya moved to the Grand Ronde Reservation along with various other Oregon bands where they remained from 1856 to 1954. In 1954, a trust relationship between the federal government and the Tribes of Western Oregon left the Grand Ronde people landless for 30 years. In 1983, Congress restored the trust relationship and recognized the Grand Ronde tribe as a sovereign nation. With the reestablishment of the reservation, the Tribe now works to build a self-sufficient community.

Other exhibits are on Women and Children, Families, and Historic Preservation. You’ll see toys and school desks, an old-fashioned stove and dry sink, and an iron that worked without electricity. You’ll see wallboards on such topics as chores at home, childbirth, and women outside the home.

THE BOON HOUSE

John Boon, a Wesleyan Methodist minister, born in Athens, Ohio, came over the Oregon Trail in 1845. He was involved in several business ventures. Boon was one of 27 organizers of the Pacific Telegraph Company linking Portland to Corvallis. It was Oregon’s first telegraph line. He was also commissioner of the California Railroad Company that incorporated in 1854. Active in politics, he was the last Territorial and first State Treasurer in Oregon.

As a backer for the Willamette Woolen Manufacturing Company, he pushed for the development of the Salem Ditch. It connected Mill Creek to the Santiam River, assuring a strong water supply to power Salem’s various industries. The same mill race that powered the Thomas Kay Woolen Mill is fed by Mill Creek.

This home is the oldest single family house still standing in Salem. It was originally located next to the building known as Boon’s Treasury, built by Boon and his son, and served as Oregon’s first State Treasury.

Exhibits in this house are on The Boon Family, The Oregon Trail, and Early Industry and Agriculture. The Oregon Trail displays cover the idea that people who came to Oregon were from such countries as Germany, Switzerland, and Russia. They were a very diverse group. The exhibit also discusses the idea of Manifest Destiny and the perils of the Oregon Trail such as terrain, accident, and disease.

Early Industry and Agriculture concentrate on the fact that the Willamette Valley became known as an agricultural hub rich with orchards and farms. Marionberries were developed in Marion County and named for the county. The county was named for Francis Marion, an American Revolutionary War military officer.

PLEASANT GROVE PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH

This church dates to 1858. It was called the “Condit Church” for its founding minister, Reverend Phillip Condit, who arrived with his family from Pennsylvania in 1854. Built as a community effort, its doors, windows, sashes, pews, and a pulpit were all handmade by volunteers. Unfortunately, Condit didn’t live to see his church completed.

Representing a meetinghouse-style associated with early country churches, it’s the oldest surviving Presbyterian Church in the Pacific Northwest. It was moved from near Aumsville, 15 miles away, to the Center’s grounds in 1984 and is currently rented out for special events.

THOMAS KAY WOOLEN MILL

During the late 1800's, the Salem area was a vast wool processing area because of the abundance of water and sheep. The mill received strong financial support when it was established in 1889. In just three weeks, the business community raised $20,000 to help secure the mill for Salem. It employed one out of every five non farming workers.

In December 1895, a fire burned the main building to the ground. Within six months, due to community support, it was in operation again. It ran continuously even through the Depression and a strike in 1934. During World War I, World War II, and the Korean War, productivity increased when it supplied blankets and uniforms to the U.S. Army. It closed in 1962 primarily because of competition from synthetic materials such as polyester and because the machines didn’t get upgraded.

The mill was founded by Thomas Lister Kay, who was an immigrant from England, and his wife. He apprenticed in England then worked for Brownsville Woolen Mill, Oregon’s second woolen mill. After becoming a partner in that mill, he sold his interest and started his own company. Three generations of Kays ran it after him.

His daughter, Martha Ann, better known as Fannie, worked at the Brownsville Mill with her father then at his mill. When Thomas Kay Woolen Mill was turned over to her brother, Thomas Benjamin Kay, she and her husband, Charles Bishop, purchased the bankrupt Pendleton Woolen Mill in 1909. It was later managed by their sons, Clarence and Roy. The Bishop family still operates Pendleton today.

TOUR OF THE MILL

By touring the mill, you will learn that the manufacture of woolen products such as blankets, for which it was known, was a complex process involving a number of steps. It wasn’t just spinning and weaving. You’ll also learn it was water power in action as the mill did not use electricity in processing until 1941. The water fell at this mill 12 feet to turn the two turbines, including the one main one.

Your first stop is the Mentzer Machine Shop named for millwright Wayne Mentzer, who served this occupation for sixty years. His work took place in that shop. The moving machinery and tools on display are original to the mill. They were used for everything from making machine parts to repairing structures.

Walk down the stairs and through the shelter and you’ll pass the crown gears. These transferred motion from the vertical turbine to the horizontal shaft that powered all of the main building’s machinery.

Next is the picker building where fleece was picked clean of burrs, grass, feces, and pests. Another type of picking took place as well. Snaps and zippers were cut off then other machines picked wool products to recycle their fibers. This was made into less expensive “shoddy” wool.

During the mill’s operation, dyeing was done in a series of interconnected sheds and buildings. These are gone today, and the dyeing process is portrayed in a mural on the mill building’s south wall. It sometimes took three hours to get the right color. The color went into the mill race.

You will reach the mill building after going through the scouring building which housed machines to scour the dirty wool. The process was very slow because wool becomes felt if agitated too much.

Whether you go with a guide or by yourself, the mill building covers the steps from carding to pressing and final inspection. Each of the steps has wallboards which explain what you will be seeing.

The Weaver’s Guild meets on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Fridays. Take the elevator to the fourth floor to watch them in action. Then take an elevator to the second floor to see carding, spinning, dressing (setting up the loom), weaving, and perching in that order. This is where we found going with a guide was useful since she explained each of the processes and demonstrated parts of the loom.

We learned after weaving, that the fabric was hung on a “perch” for inspection. After imperfections were marked, the cloth was cut and dropped through a trap door. It was then weighed, measured, ticketed, and passed to the burlers and finishers in the mending room below.

The rest of the procedure was done downstairs. The burler’s job was to find and remove knots, bunches, and loose ends. He then marked any “runs” to which menders added needed fabric. The menders rewove the fabric by hand when threads were missing.

At the fulling mills, they used warm water and soap to conduct a controlled shrink so that the material came together. The fabric was washed of all soap and dirt after fulling. Then an extractor, by spinning, squeezed excess water out of the fabric. During the early days, the fabric was stretched out on long racks called “tenterhooks” on the fourth floor. In 1941, a machine dryer was used in a shed attached to the first floor.

Nap or pile on the fabric was raised by using nappers with wire-covered rollers. These replaced the teasels with 2,500 to 4,000 heads that lasted six hours. We learned from our guide that New York and Oregon are the largest two teasel states in the nation. Then the pile was trimmed with a shearing machine.

A steam press smoothed the fabric giving it a finished look. An inspector looked for any final imperfections. Then the blankets were bound, folded, rolled, weighed, and labeled. Orders were readied for shipping.

DETAILS

The Willamette Heritage Center is located at 1313 Mill Street SE in Salem. Its phone number is (503) 585-7012. Hours are Monday through Saturday 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Access to the grounds is free. Visiting the museum is $7.00 Adults, $6.00 Seniors (65 +), $4.00 Students (with ID), $3.00 Youth (6 - 17) and children under age five free.

Entrance Building at Willamette Heritage Center

Jason Lee

Jason Lee House, Youngsters from TIP

Jason Lee Apartment

Jason Lee's Writing Desk and Bible

Blacksmithing Tools at Jason Lee House

The Parsonage

School Desks at the Parsonage

Stove at Parsonage

The Boon House

Pleasant Grove Presbyterian Church

Carding Machine

Work by Salem Fiberarts Guild

Weaver's Guild in Action

Carding Machine

Spooling Machine

Automatic Loom

Thomas Kay Mill Building

Dye House