Hello Everyone,

Valdez, the terminus of the Trans-Alaska pipeline, has become popular with tourists. If you're headed to this town of around 3,800 in population, take the time to explore its three quality museums. Each has a different slant.

VALDEZ MUSEUM & HISTORICAL ARCHIVE

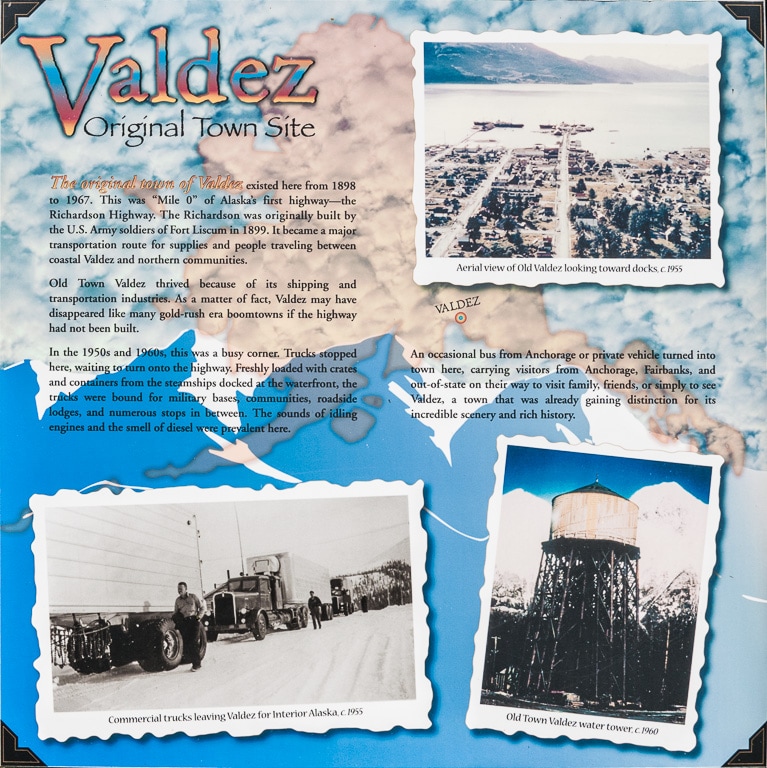

The Valdez Museum (VMHA), whose exhibits cover 12,700 square feet of space, is divided into two buildings which are four blocks apart. The museum on Egan traces the heritage and culture of Valdez, the Copper River Valley, and Prince William Sound from the Native Americans to modern times. It does this through permanent exhibits consisting of artifacts, textiles, photographs, and documents. Its annex at Hazelet relates the story of Old Valdez which was devastated during the 1964 Good Friday earthquake.

Exhibits at Egan tell such stories as native cultures, early exploration, the gold rush, the founding of Valdez, mining, and the Richardson Highway. They also relate the pipeline’s history, the Exxon Valdez oil spill, and the history of Alaskan Bush pilots. On display are two restored turn-of-the-century fire engines and a lighthouse lens from Prince William Sound as well as the recreation of a prospector’s cabin and an early Valdez parlor.

UP FRONT

Near the museum’s entrance are two permanently displayed, fully restored vehicles: an 1886 Gleason & Bailey hand pumper fire engine and a 1907 Ahrens steam water pumper. Adjacent space is usually devoted to a temporary art show of some type.

You’ll also see a Fresnel lens from the Hinchinbrook Lighthouse built in 1910. The light marked the entrance to Prince William Sound and was located 88 miles from Valdez. Due to earthquake damage in the late 1920s, the lighthouse was replaced in 1934. A two- headed aero beacon replaced the lens in 1967. By 1974, the lighthouse beam was fully automated. The lens produced a white flash every five seconds and was seen as far away as 22 miles.

NATIVE CULTURES

The museum has dedicated 600 feet to its Alaska Native Gallery. Through permanent and temporary exhibits, it includes antiquities and contemporary Alaska native artwork. It also interprets the history and culture of those who made Prince William Sound and Copper River Basin. One display covers salmon fishing in the Sound. Be sure to watch the video on the fish wheel and observe the fishing equipment.

While Alaskan natives did not have a permanent home in the area before Valdez’s founding by white settlers, they did use the land for hunting and fishing. Prince William Sound and the Copper River Basin were occupied by several different cultures.

One group is the Ahtna, an Athabascan tribe who prefer to call themselves “Copper River Natives.” That is because Ahtna refers to a specific region. The Eyaks also live in the Copper River Delta. Although they have their own distinct language and culture, they have often associated with such Northwest Coast tribes as the Tlingit and Ahtna through trade. The Alutilq refer to themselves as Sugpiaq and live around Prince William Sound and the Alaska Peninsula. They are a maritime people sharing cultural traits with the Aleut and Yup’iks.

EXPLORATION

Alaska became a prime spot for exploration in the 18th century. By 1785, the Russians had established a foothold in Prince William Sound by constructing a trading post on Hinchinbrook Island. Spain and England sent explorers and established commercial ventures of their own to secure their claims. The Spanish explorer Fidalgo named Valdez in 1790 after the Spanish naval officer Antonio Valdés y Fernández Bazán. Italy, Denmark, France, and Germany participated by sending seamen and scientists as part of these expeditions.

Until 1867, when the United States purchased Alaska from Russia, the U.S. failed to explore the territory. It was after the Alaska Commercial Company took over the Russian America Company’s holdings that American prospectors, trappers, fishermen, and military personnel settled the coastal regions. In the 1880s, the United States government started reconnaissance missions to the Alaskan interior.

GOLD RUSH

While prospectors had previously traveled the Calced Trail, White Pass Trail, or gone by boat via the Yukon River to St. Michael’s, others preferred a shorter route to the Alaskan interior. The Pacific Steam Whaling Company, who operated a cannery at Orca Bay (modern Cordova) and a small trading post at Port Valdez, saw an opportunity for financial gain by bringing prospectors north. They advertised an “All-America Route” running from Valdez to the interior via the Valdez Glacier and Klutina River.

Although it was a scam to lure prospectors off the Klondike Gold Rush, newspapers and outfitters heralded this announcement. Unfortunately, the glacier trail was twice as long and steep as reported. Crossing was treacherous and ended in a land where gold was not easily discovered. Many men died, including a number from scurvy, attempting the crossing.

In 1898, more than 4,000 prospectors crossed the Valdez Glacier at the head of Port Valdez. Their destinations ranged from the Klondike gold fields in the Yukon to Alaska’s Copper River area. All came via Valdez to use this “All-America Route.”

The first arrivals found Valdez consisted of a few tents. Since no towns or camps had been established, the miners set up a series of temporary camps where they stopped for meals and shelter along their journey. After they reached the interior, they set up a few small villages with Copper Venter being the largest. Most returned to Valdez via the same route in the fall. By March 1898, Valdez had a tent city of 700 to 900 inhabitants.

In this museum section, you’ll see samples of gold and quartz and a collection of miners’ tools.

MINING and TRAVERSING THE GLACIER

The Valdez Museum’s mining exhibit includes artifacts from hard rock and placer mining. Take time to view the 1920's interior of the miner’s cabin. The display, refurbished in 2011, has “A Scent of Gold,” an interactive scratch and sniff booklet. If you scratch the stickers you can smell gunpowder, a wood stove, and tanned leather. The cabin’s exterior has three-dimensional models describing the methods of cabin construction. Visitors will also see a touchable display of pelts.

Very few prospectors were successful. By 1910, hard-rock mining run by corporations eclipsed panning for gold along the river beds. One was the Cliff Gold Mining Company which ran the Cliff Mine off the glacier moraine of Shoup Glacier. The mine operated until 1942. Towns sprang up in Prince William Sound such as McCarthy, a company town serving Kennecott Mining Company in the Wrangell Mountains.

Placer mining did continue. Prospectors’ cabins can still be found in the backwoods along the Copper River Basin today.

P.S. HUNT

Hunt was a gold rush prospector who came to Valdez in 1898. He started a commercial photography business in 1901. Like others, he shot portraits, but he also photographed every gathering, ship, business, and residence. In all, he took thousands of photographs of Valdez during the entire period he lived there before leaving to work on the Alaska Railroad in 1916.

Because of Hunt, Valdez has almost a complete visual history of the first 20 years of its existence. Since his shots are dated and captioned, his subjects have been identified. You can see several of his photographs at the museum.

RAILROADS

From 1901 to 1909, the possibility of a railroad formation caused great interest in Valdez. Two railroads competed against each other. The Copper River & Northwestern Railway carved its route through Keystone Canyon. Backed by the Guggenheim and Morgan families, they had the means to do it. Alaska Home Railway organized by H. D. Reynolds vowed to build a locally-sponsored railroad.

On September 25, 1907, a shootout occurred between the two companies with one death and several injuries. That event ended Valdez’s hope of being the railroad link from the tidewater to the Kennecott Copper Mine. The Guggenheims selected Cordova instead. The mine was one of the richest copper ore deposits on the continent.

PARLOR

After the Gold Rush, Valdez’s population dropped from 7,000 in the 1910's to around 1,000 in 1920. Valdezans still took pride in their home adding such amenities as electricity, telephones, and radios. A parlor was a common feature with many containing a piano. You can see a replica of such a parlor at the museum.

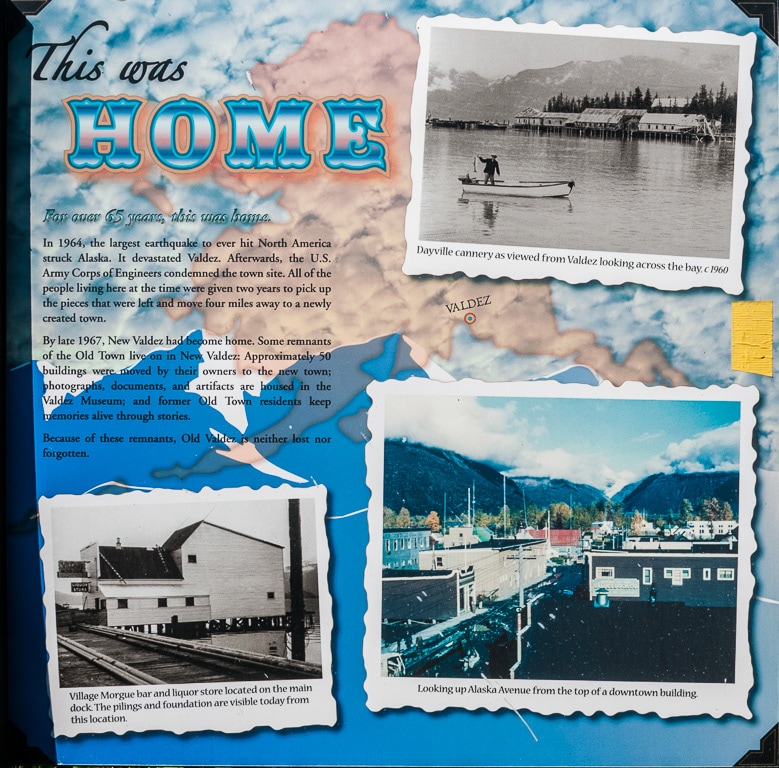

VALDEZ TRAIL - RICHARDSON HIGHWAY

Before the Richardson Trail, all trails traversed parts of Canada. The U. S. Army sought an alternative route to Alaska’s interior which was an "All America Trail." By 1901, they constructed a 5-foot wide horse pack trail to the Yukon’s Eagle City. Named for Major Wilds Preston Richardson, first president of the Alaska Board of Road Commissioners, it became known as the “Richardson Trail.” With the trail leading through Keystone Canyon and Thompson Pass, the transport of supplies, mail, and people became easier between Valdez and Fairbanks.

In 1916, the Alaska Board of Road Commissioners surfaced the road with gravel and also re-graded it providing improved access for vehicles. However, it wasn’t suitable for private drivers until the late 1920s. This two-lane highway, known as the Richardson Highway, runs today 371 miles from Valdez to Fairbanks.

This museum section also covers early tourism. Food, lodging, and transportation services were offered at the turn of the century. By the 1920's, residents had businesses catering to tourists. It took two days to travel from Fairbanks to Valdez.

FORT LISCUM

In 1890, Adam Swan established a small trading post which he called Swanport. It was the jumping off place for prospectors who headed across the Valdez Glacier. Fort Liscum, a military reservation, was established east of Swanport in 1900.

During the 1930's, Andrew and Oma Belle Day bought the army facilities and named it Dayville. They established a farm, fish cannery, sawmill, one room school, and general store. In 1969, Alyeska acquired it for their Alyeska Pipeline Terminal, completed in 1977. The first oil arrived at 11:02 p.m. on July 28, 1977 and was shipped out four days later on the tanker, Arco Juneau.

PINZON BAR

For many years, the Pinzon Bar was the center for socializing and the unofficial headquarters of Alaska’s Democrat Party. It was owned by Clinton J. Egan, the brother to Alaska’s first elected governor, Bill Egan. It was permanently closed the day of the 1964 earthquake.

At the museum, staff has recreated the 40-foot bar, reported as the longest in the Territory of Alaska. The bar was manufactured in Chicago then brought around South America to the Pacific Coast. It was used in Seattle before being brought to Valdez.

The copper sheet in its front was a remnant of Prohibition. During that period, it became a soda fountain and holes were drilled in the bar for spigots. With the repeal of Prohibition, copper sheeting covered the holes. You can see that copper sheet in the front of the bar today.

EXXON VALDEZ OIL SPILL

On March 24, 1989, the oil tanker Exxon Valdez ran aground on Blight Reef spilling an estimated 10.8 million U.S. gallons of oil into Prince William Sound. This display talks about the ship, the environmental impact and recovery of this spill and Valdez’s role in this tragedy.

HOLLAND AMERICA

On October 4, 1980, Holland America cruise line’s Prisendam's engine room caught fire in the Gulf of Alaska. All 324 passengers and 200 crew abandoned ship and were saved. The Prisendam lifeboat that arrived in Valdez is on display just outside the museum.

AVIATION

Aviation has always been an essential mode of transportation in Alaska with the state home to several well-known bush pilots. Through an interactive map and eight short videos, the museum informs visitors about the Alaskan bush pilot’s heyday while telling their individual stories. A mannequin wears authentic gear from pilots Owen Meals and Robert Campbell Reeve.

GOOD FRIDAY EARTHQUAKE

In this section, the museum tells the story of the Good Friday earthquake, the tsunami which followed, and its devastating effects on Old Valdez. For an expanded display and to see a room full of a detailed model of what Old Valdez looked like, visit the annex on Hazelet.

VALDEZ MUSEUM ON HAZELET

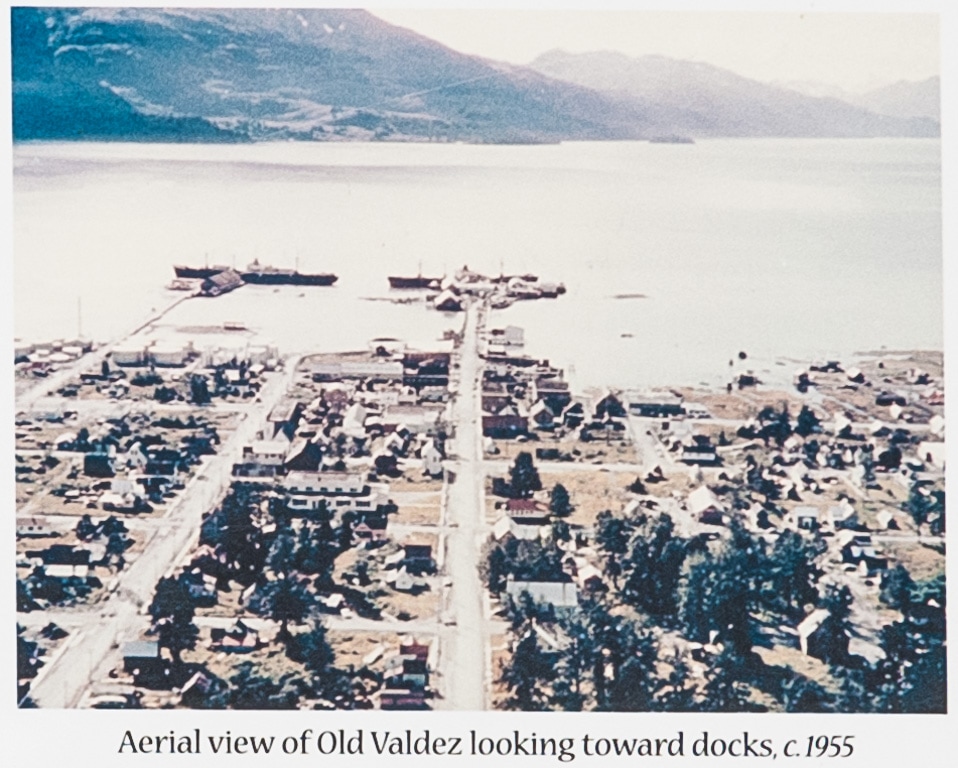

This museum relates the history of the 1964 Good Friday Earthquake which devastated the city of Valdez. The movie “Between the Glacier & The Sea” can be seen at both museums. Produced in 2008, it tells the story of the 1964 Great Alaska Earthquake and its impact on Valdez. It also traces the town’s founding and eventual demise. You’ll see actual footage of the quake’s impact and hear firsthand accounts of its survivors. It’s shown continuously.

It had been built on a glacial moraine that liquefied when the earthquake struck causing a large section of the delta (about 4,000 feet long by 600 feet wide) to slump into the waters of Port Valdez. This sent most of the town’s port facilities to the bottom displacing a large amount of water and causing a local tsunami. The town had no warning, and all 32 people on the dock were killed. They had been on the city’s main freight dock to help with and watch the unloading of the SS Chena, a supply ship. No deaths occurred elsewhere in town.

The combined effects of the earthquake and the 30 to 40-foot tsunami destroyed most of the waterfront and caused damage for three to four blocks inland. These forces caused the Union Oil Company tanks to rupture, starting a fire that spread across the remaining waterfront. Smaller waves from the tsunami fortunately had minimal effect.

Residents lived in town until 1967 as a new site was prepared on more stable ground under the guidance of the Army Corps of Engineers. Private contractors built the new community - first a port and harbor with a ferry terminal then businesses and homes. They transported 54 houses and buildings by truck to the new site to reestablish new Valdez. A new elementary school and hospital were constructed.

The fire department played a final role in closing Old Valdez. Fearing squatters and trespassers, Old Town’s remaining structures were razed in a controlled burn in 1967. This allowed a training opportunity for firefighters throughout Alaska.

The centerpiece of this museum is the 1:20 model of Old Town Valdez as it appeared before the massive 1964 earthquake. This extensive model consists of 11 pods. If they were pushed together, it would be an exact replica of Valdez on a weekday when the S. S. Chena docked in town. Walking between the pods is like walking down the streets in the former town.

It was prepared in 1997 by scale model artist, Sue Fowler. According to the booklet Remembering Old Valdez, “Fowler used 500 x-acto blades, 10 gallons of sifted sand, four bags of yarrow, five gallons of glue, two quarts of rubber cement, eight bags of lichen, four cans of spray paint, and sheets and sheets of mat board to create the town model depicting Valdez as it was in the Summer of 1963.”

As her reference, she used five volumes of maps and archived photographs detailing the 350 buildings standing after the earthquake. Fowler also used slides, 8mm movies, and documents with first-hand accounts from people who lived in Old Town. She then spent a year building the model’s stores and houses. An average house took five hours to build while buildings took between eight and twelve hours. The model contains more than 400 buildings and 60 city blocks.

Details include window boxes, period automobiles, pets, and signs. She used dried yarrow to create her cottonwood and made spruce trees out of furnace filters. She used local lichen and gravel from the Old Town site to create her ground cover. Finishing details of miniatures and accessories were pre-ordered. Markers on the buildings were added in 2012 noting what buildings relocated to new Valdez.

You’ll want to check out the Held House, an actual top portion of an original house from Old Valdez. It contains artifacts and furnishings from Old Town. Firefighting equipment and vehicles are also on exhibit. The city’s fire department was run from 1901 until 1967 by volunteers. Displayed vehicles include a 1942 Ford fire truck, a 1923 Ford Model T Chemical Truck, and a 1953 Willys Jeep.

Other exhibits include an interactive earthquake exhibit consisting of an operating seismograph, computer simulations, and a shake table. A huge billboard provides information on the earthquake’s tragic effects in various Alaskan towns and villages.

For example, in Anchorage, damage was done to 30 city blocks which were mostly downtown. A landslide devastated 130 acres of residential property at Turnagain Heights destroying 85 homes. Nine people were killed including one at the airport.

Seward was among those hit hardest by the tsunami. The town shook violently within 30 seconds of the quake destroying much of the waterfront which collapsed and fell into the sea. Wakes were up to 30 feet high. The Standard Oil Company dockside fuel tanks blew up. The tsunami acted liked a wall of fire spreading across the water destroying the Texaco Petroleum facilities. It burned the Alaska Railway docks, the electrical plant, and many homes. Much of the town was destroyed by a combination of fire and water. Twelve died.

In Whittier, three tsunami waves hit the town in quick succession. The first wasn’t particularly destructive, but the second and third reached heights of 40 feet carrying boulders, weighing up to two tons, some 125 feet inland. Thirteen were killed.

Chenega, the largest occupied native village in Prince William Sound, was destroyed by tsunami waves as high as 90 feet. They killed 23 of 68 villagers. Only the school and one house remained intact.

You will find the Valdez Museum & Historical Archive at 217 Egan Drive and on 436 Hazelet Street. From mid May to mid September, hours are 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. daily. In the winter, Egan is openTuesday to Sunday 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. while Hazelet is by appointment. The telephone number at Egan is (907) 835-2764 while the phone number at Hazelet is (907) 835-5407. Admission to both museums is $8 for adults, $6 for seniors (ages 60+), $5 for ages 14-17, and free for ages 13 and under.

After this museum, you can visit Old Town Valdez, located four miles from town. Most is marshland since all that remains are dock pilings, the post office foundation, and gravel roads. The post office, now a memorial, has signs displaying the names of earthquake victims. Historical markers indicate the former locations of Hotel Valdez and the old Klip Joint, the town’s only barber shop. Signs explain through text and photos Old Town's history.

MAXINE AND JESSE WHITNEY MUSEUM

Though small in size, this museum is touted to contain one of the largest collections of Alaska Native art and artifacts in the world. It also has an outstanding collection of wildlife taxidermy specimens.

It contains the collection of the Whitneys, who came to Alaska in 1947. By traveling to various Native villages through the Alaska territory, Maxine Whitney purchased items directly from artists to sell in her gift shop. She assumed ownership of Fairbanks’ Eskimo Museum in 1969 and continued collecting until the mid 1980's. Whitney donated her entire collection in 1998 to Prince William Sound Community College under the stipulation that everything would stay together. The current museum site opened in May 2008.

The Whitneys collected mammoth bones, teeth, and tusks from collection sites, where they were exposed by the large machinery. Many of these bones were fossilized and in various conditions. The Narwhale tusk is 95 inches long. Narwhales have one, rarely two tusks protruding from their mouth.

Maxine collected many arrow heads. These range in size from tiny bird points to larger game points. Some come from the Midwest as well as Alaska. Most are of red or grey chert, basalt, obsidian, and shale.

Taxidermy mounts consist of a moose, black bear, grizzly bear, polar bear, musk ox, and bison. Others are of a red fox, wolves, lynx, marten, sled dogs, mountain lion, a caribou, and a bearded seal. Even a Tundra swan, two snow geese, and Dall sheep are represented. Of particular interest is the moose who stands 8 feet tall and whose antlers span 5 feet 8 inches across. He is among the largest mounted moose in existence. He’s the museum mascot.

The museum also contains many animal furs including a beaver, wolf, muskrat, and fox. Seal skins are also here including the spotted seal, ribbon seal, and harbor seal. These animals are now protected since the 1972 Marine Mammal Protection Act prohibits hunting of these creatures.

Native American artifacts range from totem poles and basketry to ulu knives, halibut hooks, a small fish wheel, and sewing kits. Alaska Natives carried sewing kits since they didn’t have tailors or department stores. They were made of leather, baleen, and ivory.

You will also find fishing net weights or sinkers, a seal oil lamp, and balls used as playthings. One mug was made from the jawbone of a walrus while another dated to prehistoric times. The collection has numerous containers made from grasses, bark, and other plant fibers. It also has native boats, a kayak, and a model of a fishing wheel.

Clothing can also be found here. You can view a Tlingit jacket, Athabascan dance boots, a diaper made from seal skin, Eskimo moose skin pants, and a moose gut bag. The museum contains a number of masks which for native cultures had many different uses. Some were used in ceremonies while others were tourist items. Some were made of whale bone while others were surrounded by fur.

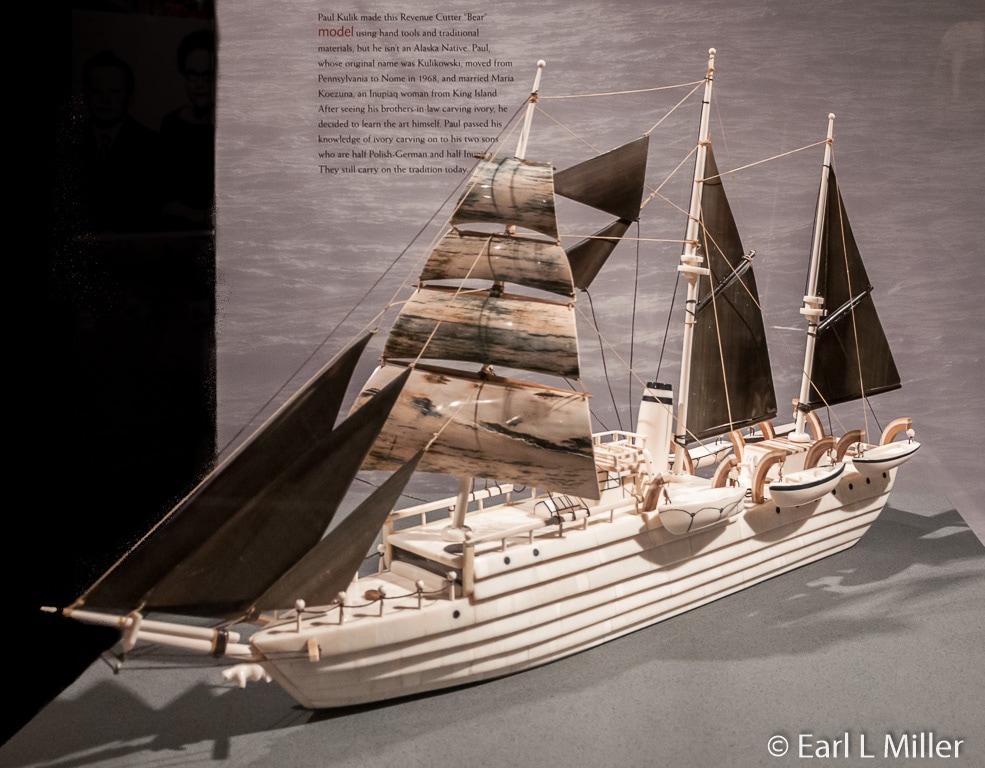

The Paul Kulik History of Transportation collection should not be missed. He was an electrician who moved from Pennsylvania to Alaska in the 1960's. He married an Inupiaq woman and started carving ivory after watching his brothers-in-law making a living from this art. Mrs. Whitney commissioned this collection. It includes a man walking on snow shoes, a five dog sled team, a “Jenny Biplane,” and a snow machine. His model of the Revenue Cutter, “Bear” included mitered pieces of ivory that were layered over a full walrus tusk. The sails were mostly baleen.

The couch made from moose antlers grabbed my attention. I would have been tempted to take it home if it had been for sale.

The Maxine and Jesse Whitney Museum is located at Prince William Sound College at 303 Lowe Street. Their telephone number is (907) 834-1690. Admission is free. From Memorial Day weekend to Labor Day weekend, hours are 9:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m. daily. The rest of the year they are open by appointment only.

Valdez, the terminus of the Trans-Alaska pipeline, has become popular with tourists. If you're headed to this town of around 3,800 in population, take the time to explore its three quality museums. Each has a different slant.

VALDEZ MUSEUM & HISTORICAL ARCHIVE

The Valdez Museum (VMHA), whose exhibits cover 12,700 square feet of space, is divided into two buildings which are four blocks apart. The museum on Egan traces the heritage and culture of Valdez, the Copper River Valley, and Prince William Sound from the Native Americans to modern times. It does this through permanent exhibits consisting of artifacts, textiles, photographs, and documents. Its annex at Hazelet relates the story of Old Valdez which was devastated during the 1964 Good Friday earthquake.

Exhibits at Egan tell such stories as native cultures, early exploration, the gold rush, the founding of Valdez, mining, and the Richardson Highway. They also relate the pipeline’s history, the Exxon Valdez oil spill, and the history of Alaskan Bush pilots. On display are two restored turn-of-the-century fire engines and a lighthouse lens from Prince William Sound as well as the recreation of a prospector’s cabin and an early Valdez parlor.

UP FRONT

Near the museum’s entrance are two permanently displayed, fully restored vehicles: an 1886 Gleason & Bailey hand pumper fire engine and a 1907 Ahrens steam water pumper. Adjacent space is usually devoted to a temporary art show of some type.

You’ll also see a Fresnel lens from the Hinchinbrook Lighthouse built in 1910. The light marked the entrance to Prince William Sound and was located 88 miles from Valdez. Due to earthquake damage in the late 1920s, the lighthouse was replaced in 1934. A two- headed aero beacon replaced the lens in 1967. By 1974, the lighthouse beam was fully automated. The lens produced a white flash every five seconds and was seen as far away as 22 miles.

NATIVE CULTURES

The museum has dedicated 600 feet to its Alaska Native Gallery. Through permanent and temporary exhibits, it includes antiquities and contemporary Alaska native artwork. It also interprets the history and culture of those who made Prince William Sound and Copper River Basin. One display covers salmon fishing in the Sound. Be sure to watch the video on the fish wheel and observe the fishing equipment.

While Alaskan natives did not have a permanent home in the area before Valdez’s founding by white settlers, they did use the land for hunting and fishing. Prince William Sound and the Copper River Basin were occupied by several different cultures.

One group is the Ahtna, an Athabascan tribe who prefer to call themselves “Copper River Natives.” That is because Ahtna refers to a specific region. The Eyaks also live in the Copper River Delta. Although they have their own distinct language and culture, they have often associated with such Northwest Coast tribes as the Tlingit and Ahtna through trade. The Alutilq refer to themselves as Sugpiaq and live around Prince William Sound and the Alaska Peninsula. They are a maritime people sharing cultural traits with the Aleut and Yup’iks.

EXPLORATION

Alaska became a prime spot for exploration in the 18th century. By 1785, the Russians had established a foothold in Prince William Sound by constructing a trading post on Hinchinbrook Island. Spain and England sent explorers and established commercial ventures of their own to secure their claims. The Spanish explorer Fidalgo named Valdez in 1790 after the Spanish naval officer Antonio Valdés y Fernández Bazán. Italy, Denmark, France, and Germany participated by sending seamen and scientists as part of these expeditions.

Until 1867, when the United States purchased Alaska from Russia, the U.S. failed to explore the territory. It was after the Alaska Commercial Company took over the Russian America Company’s holdings that American prospectors, trappers, fishermen, and military personnel settled the coastal regions. In the 1880s, the United States government started reconnaissance missions to the Alaskan interior.

GOLD RUSH

While prospectors had previously traveled the Calced Trail, White Pass Trail, or gone by boat via the Yukon River to St. Michael’s, others preferred a shorter route to the Alaskan interior. The Pacific Steam Whaling Company, who operated a cannery at Orca Bay (modern Cordova) and a small trading post at Port Valdez, saw an opportunity for financial gain by bringing prospectors north. They advertised an “All-America Route” running from Valdez to the interior via the Valdez Glacier and Klutina River.

Although it was a scam to lure prospectors off the Klondike Gold Rush, newspapers and outfitters heralded this announcement. Unfortunately, the glacier trail was twice as long and steep as reported. Crossing was treacherous and ended in a land where gold was not easily discovered. Many men died, including a number from scurvy, attempting the crossing.

In 1898, more than 4,000 prospectors crossed the Valdez Glacier at the head of Port Valdez. Their destinations ranged from the Klondike gold fields in the Yukon to Alaska’s Copper River area. All came via Valdez to use this “All-America Route.”

The first arrivals found Valdez consisted of a few tents. Since no towns or camps had been established, the miners set up a series of temporary camps where they stopped for meals and shelter along their journey. After they reached the interior, they set up a few small villages with Copper Venter being the largest. Most returned to Valdez via the same route in the fall. By March 1898, Valdez had a tent city of 700 to 900 inhabitants.

In this museum section, you’ll see samples of gold and quartz and a collection of miners’ tools.

MINING and TRAVERSING THE GLACIER

The Valdez Museum’s mining exhibit includes artifacts from hard rock and placer mining. Take time to view the 1920's interior of the miner’s cabin. The display, refurbished in 2011, has “A Scent of Gold,” an interactive scratch and sniff booklet. If you scratch the stickers you can smell gunpowder, a wood stove, and tanned leather. The cabin’s exterior has three-dimensional models describing the methods of cabin construction. Visitors will also see a touchable display of pelts.

Very few prospectors were successful. By 1910, hard-rock mining run by corporations eclipsed panning for gold along the river beds. One was the Cliff Gold Mining Company which ran the Cliff Mine off the glacier moraine of Shoup Glacier. The mine operated until 1942. Towns sprang up in Prince William Sound such as McCarthy, a company town serving Kennecott Mining Company in the Wrangell Mountains.

Placer mining did continue. Prospectors’ cabins can still be found in the backwoods along the Copper River Basin today.

P.S. HUNT

Hunt was a gold rush prospector who came to Valdez in 1898. He started a commercial photography business in 1901. Like others, he shot portraits, but he also photographed every gathering, ship, business, and residence. In all, he took thousands of photographs of Valdez during the entire period he lived there before leaving to work on the Alaska Railroad in 1916.

Because of Hunt, Valdez has almost a complete visual history of the first 20 years of its existence. Since his shots are dated and captioned, his subjects have been identified. You can see several of his photographs at the museum.

RAILROADS

From 1901 to 1909, the possibility of a railroad formation caused great interest in Valdez. Two railroads competed against each other. The Copper River & Northwestern Railway carved its route through Keystone Canyon. Backed by the Guggenheim and Morgan families, they had the means to do it. Alaska Home Railway organized by H. D. Reynolds vowed to build a locally-sponsored railroad.

On September 25, 1907, a shootout occurred between the two companies with one death and several injuries. That event ended Valdez’s hope of being the railroad link from the tidewater to the Kennecott Copper Mine. The Guggenheims selected Cordova instead. The mine was one of the richest copper ore deposits on the continent.

PARLOR

After the Gold Rush, Valdez’s population dropped from 7,000 in the 1910's to around 1,000 in 1920. Valdezans still took pride in their home adding such amenities as electricity, telephones, and radios. A parlor was a common feature with many containing a piano. You can see a replica of such a parlor at the museum.

VALDEZ TRAIL - RICHARDSON HIGHWAY

Before the Richardson Trail, all trails traversed parts of Canada. The U. S. Army sought an alternative route to Alaska’s interior which was an "All America Trail." By 1901, they constructed a 5-foot wide horse pack trail to the Yukon’s Eagle City. Named for Major Wilds Preston Richardson, first president of the Alaska Board of Road Commissioners, it became known as the “Richardson Trail.” With the trail leading through Keystone Canyon and Thompson Pass, the transport of supplies, mail, and people became easier between Valdez and Fairbanks.

In 1916, the Alaska Board of Road Commissioners surfaced the road with gravel and also re-graded it providing improved access for vehicles. However, it wasn’t suitable for private drivers until the late 1920s. This two-lane highway, known as the Richardson Highway, runs today 371 miles from Valdez to Fairbanks.

This museum section also covers early tourism. Food, lodging, and transportation services were offered at the turn of the century. By the 1920's, residents had businesses catering to tourists. It took two days to travel from Fairbanks to Valdez.

FORT LISCUM

In 1890, Adam Swan established a small trading post which he called Swanport. It was the jumping off place for prospectors who headed across the Valdez Glacier. Fort Liscum, a military reservation, was established east of Swanport in 1900.

During the 1930's, Andrew and Oma Belle Day bought the army facilities and named it Dayville. They established a farm, fish cannery, sawmill, one room school, and general store. In 1969, Alyeska acquired it for their Alyeska Pipeline Terminal, completed in 1977. The first oil arrived at 11:02 p.m. on July 28, 1977 and was shipped out four days later on the tanker, Arco Juneau.

PINZON BAR

For many years, the Pinzon Bar was the center for socializing and the unofficial headquarters of Alaska’s Democrat Party. It was owned by Clinton J. Egan, the brother to Alaska’s first elected governor, Bill Egan. It was permanently closed the day of the 1964 earthquake.

At the museum, staff has recreated the 40-foot bar, reported as the longest in the Territory of Alaska. The bar was manufactured in Chicago then brought around South America to the Pacific Coast. It was used in Seattle before being brought to Valdez.

The copper sheet in its front was a remnant of Prohibition. During that period, it became a soda fountain and holes were drilled in the bar for spigots. With the repeal of Prohibition, copper sheeting covered the holes. You can see that copper sheet in the front of the bar today.

EXXON VALDEZ OIL SPILL

On March 24, 1989, the oil tanker Exxon Valdez ran aground on Blight Reef spilling an estimated 10.8 million U.S. gallons of oil into Prince William Sound. This display talks about the ship, the environmental impact and recovery of this spill and Valdez’s role in this tragedy.

HOLLAND AMERICA

On October 4, 1980, Holland America cruise line’s Prisendam's engine room caught fire in the Gulf of Alaska. All 324 passengers and 200 crew abandoned ship and were saved. The Prisendam lifeboat that arrived in Valdez is on display just outside the museum.

AVIATION

Aviation has always been an essential mode of transportation in Alaska with the state home to several well-known bush pilots. Through an interactive map and eight short videos, the museum informs visitors about the Alaskan bush pilot’s heyday while telling their individual stories. A mannequin wears authentic gear from pilots Owen Meals and Robert Campbell Reeve.

GOOD FRIDAY EARTHQUAKE

In this section, the museum tells the story of the Good Friday earthquake, the tsunami which followed, and its devastating effects on Old Valdez. For an expanded display and to see a room full of a detailed model of what Old Valdez looked like, visit the annex on Hazelet.

VALDEZ MUSEUM ON HAZELET

This museum relates the history of the 1964 Good Friday Earthquake which devastated the city of Valdez. The movie “Between the Glacier & The Sea” can be seen at both museums. Produced in 2008, it tells the story of the 1964 Great Alaska Earthquake and its impact on Valdez. It also traces the town’s founding and eventual demise. You’ll see actual footage of the quake’s impact and hear firsthand accounts of its survivors. It’s shown continuously.

It had been built on a glacial moraine that liquefied when the earthquake struck causing a large section of the delta (about 4,000 feet long by 600 feet wide) to slump into the waters of Port Valdez. This sent most of the town’s port facilities to the bottom displacing a large amount of water and causing a local tsunami. The town had no warning, and all 32 people on the dock were killed. They had been on the city’s main freight dock to help with and watch the unloading of the SS Chena, a supply ship. No deaths occurred elsewhere in town.

The combined effects of the earthquake and the 30 to 40-foot tsunami destroyed most of the waterfront and caused damage for three to four blocks inland. These forces caused the Union Oil Company tanks to rupture, starting a fire that spread across the remaining waterfront. Smaller waves from the tsunami fortunately had minimal effect.

Residents lived in town until 1967 as a new site was prepared on more stable ground under the guidance of the Army Corps of Engineers. Private contractors built the new community - first a port and harbor with a ferry terminal then businesses and homes. They transported 54 houses and buildings by truck to the new site to reestablish new Valdez. A new elementary school and hospital were constructed.

The fire department played a final role in closing Old Valdez. Fearing squatters and trespassers, Old Town’s remaining structures were razed in a controlled burn in 1967. This allowed a training opportunity for firefighters throughout Alaska.

The centerpiece of this museum is the 1:20 model of Old Town Valdez as it appeared before the massive 1964 earthquake. This extensive model consists of 11 pods. If they were pushed together, it would be an exact replica of Valdez on a weekday when the S. S. Chena docked in town. Walking between the pods is like walking down the streets in the former town.

It was prepared in 1997 by scale model artist, Sue Fowler. According to the booklet Remembering Old Valdez, “Fowler used 500 x-acto blades, 10 gallons of sifted sand, four bags of yarrow, five gallons of glue, two quarts of rubber cement, eight bags of lichen, four cans of spray paint, and sheets and sheets of mat board to create the town model depicting Valdez as it was in the Summer of 1963.”

As her reference, she used five volumes of maps and archived photographs detailing the 350 buildings standing after the earthquake. Fowler also used slides, 8mm movies, and documents with first-hand accounts from people who lived in Old Town. She then spent a year building the model’s stores and houses. An average house took five hours to build while buildings took between eight and twelve hours. The model contains more than 400 buildings and 60 city blocks.

Details include window boxes, period automobiles, pets, and signs. She used dried yarrow to create her cottonwood and made spruce trees out of furnace filters. She used local lichen and gravel from the Old Town site to create her ground cover. Finishing details of miniatures and accessories were pre-ordered. Markers on the buildings were added in 2012 noting what buildings relocated to new Valdez.

You’ll want to check out the Held House, an actual top portion of an original house from Old Valdez. It contains artifacts and furnishings from Old Town. Firefighting equipment and vehicles are also on exhibit. The city’s fire department was run from 1901 until 1967 by volunteers. Displayed vehicles include a 1942 Ford fire truck, a 1923 Ford Model T Chemical Truck, and a 1953 Willys Jeep.

Other exhibits include an interactive earthquake exhibit consisting of an operating seismograph, computer simulations, and a shake table. A huge billboard provides information on the earthquake’s tragic effects in various Alaskan towns and villages.

For example, in Anchorage, damage was done to 30 city blocks which were mostly downtown. A landslide devastated 130 acres of residential property at Turnagain Heights destroying 85 homes. Nine people were killed including one at the airport.

Seward was among those hit hardest by the tsunami. The town shook violently within 30 seconds of the quake destroying much of the waterfront which collapsed and fell into the sea. Wakes were up to 30 feet high. The Standard Oil Company dockside fuel tanks blew up. The tsunami acted liked a wall of fire spreading across the water destroying the Texaco Petroleum facilities. It burned the Alaska Railway docks, the electrical plant, and many homes. Much of the town was destroyed by a combination of fire and water. Twelve died.

In Whittier, three tsunami waves hit the town in quick succession. The first wasn’t particularly destructive, but the second and third reached heights of 40 feet carrying boulders, weighing up to two tons, some 125 feet inland. Thirteen were killed.

Chenega, the largest occupied native village in Prince William Sound, was destroyed by tsunami waves as high as 90 feet. They killed 23 of 68 villagers. Only the school and one house remained intact.

You will find the Valdez Museum & Historical Archive at 217 Egan Drive and on 436 Hazelet Street. From mid May to mid September, hours are 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. daily. In the winter, Egan is openTuesday to Sunday 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. while Hazelet is by appointment. The telephone number at Egan is (907) 835-2764 while the phone number at Hazelet is (907) 835-5407. Admission to both museums is $8 for adults, $6 for seniors (ages 60+), $5 for ages 14-17, and free for ages 13 and under.

After this museum, you can visit Old Town Valdez, located four miles from town. Most is marshland since all that remains are dock pilings, the post office foundation, and gravel roads. The post office, now a memorial, has signs displaying the names of earthquake victims. Historical markers indicate the former locations of Hotel Valdez and the old Klip Joint, the town’s only barber shop. Signs explain through text and photos Old Town's history.

MAXINE AND JESSE WHITNEY MUSEUM

Though small in size, this museum is touted to contain one of the largest collections of Alaska Native art and artifacts in the world. It also has an outstanding collection of wildlife taxidermy specimens.

It contains the collection of the Whitneys, who came to Alaska in 1947. By traveling to various Native villages through the Alaska territory, Maxine Whitney purchased items directly from artists to sell in her gift shop. She assumed ownership of Fairbanks’ Eskimo Museum in 1969 and continued collecting until the mid 1980's. Whitney donated her entire collection in 1998 to Prince William Sound Community College under the stipulation that everything would stay together. The current museum site opened in May 2008.

The Whitneys collected mammoth bones, teeth, and tusks from collection sites, where they were exposed by the large machinery. Many of these bones were fossilized and in various conditions. The Narwhale tusk is 95 inches long. Narwhales have one, rarely two tusks protruding from their mouth.

Maxine collected many arrow heads. These range in size from tiny bird points to larger game points. Some come from the Midwest as well as Alaska. Most are of red or grey chert, basalt, obsidian, and shale.

Taxidermy mounts consist of a moose, black bear, grizzly bear, polar bear, musk ox, and bison. Others are of a red fox, wolves, lynx, marten, sled dogs, mountain lion, a caribou, and a bearded seal. Even a Tundra swan, two snow geese, and Dall sheep are represented. Of particular interest is the moose who stands 8 feet tall and whose antlers span 5 feet 8 inches across. He is among the largest mounted moose in existence. He’s the museum mascot.

The museum also contains many animal furs including a beaver, wolf, muskrat, and fox. Seal skins are also here including the spotted seal, ribbon seal, and harbor seal. These animals are now protected since the 1972 Marine Mammal Protection Act prohibits hunting of these creatures.

Native American artifacts range from totem poles and basketry to ulu knives, halibut hooks, a small fish wheel, and sewing kits. Alaska Natives carried sewing kits since they didn’t have tailors or department stores. They were made of leather, baleen, and ivory.

You will also find fishing net weights or sinkers, a seal oil lamp, and balls used as playthings. One mug was made from the jawbone of a walrus while another dated to prehistoric times. The collection has numerous containers made from grasses, bark, and other plant fibers. It also has native boats, a kayak, and a model of a fishing wheel.

Clothing can also be found here. You can view a Tlingit jacket, Athabascan dance boots, a diaper made from seal skin, Eskimo moose skin pants, and a moose gut bag. The museum contains a number of masks which for native cultures had many different uses. Some were used in ceremonies while others were tourist items. Some were made of whale bone while others were surrounded by fur.

The Paul Kulik History of Transportation collection should not be missed. He was an electrician who moved from Pennsylvania to Alaska in the 1960's. He married an Inupiaq woman and started carving ivory after watching his brothers-in-law making a living from this art. Mrs. Whitney commissioned this collection. It includes a man walking on snow shoes, a five dog sled team, a “Jenny Biplane,” and a snow machine. His model of the Revenue Cutter, “Bear” included mitered pieces of ivory that were layered over a full walrus tusk. The sails were mostly baleen.

The couch made from moose antlers grabbed my attention. I would have been tempted to take it home if it had been for sale.

The Maxine and Jesse Whitney Museum is located at Prince William Sound College at 303 Lowe Street. Their telephone number is (907) 834-1690. Admission is free. From Memorial Day weekend to Labor Day weekend, hours are 9:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m. daily. The rest of the year they are open by appointment only.

Valdez Museum on Egan

Fire Fighting Equipment at the Museum's Front - 1907 Aherns Steam Water Pumper

Interior of the Replica 1920's Miner's Cabin

First President of the Alaska Board of Road Commissioners

Historic Signs from Richardson Highway

40 Foot Pinzon Bar - Longest in the Territory of Alaska

Interior of Valdez Museum Annex on Hazelet

Historic Sign at Old Town Site

Close Up of Sign - Showing Aerial Perspective of Old Town

Another Historic Sign at Old Town Site

Mascot of the Maxine and Jesse Whitney Museum

Polar Bear

Musk Ox

Lynx

Alaska Native Boats, Kayak, and Fish Wheel Models

Athabascan Dance Boots

Part of Paul Kulik History of Transportation Collection

Paul Kulik's Model of the Revenue Cutter "Bear"

Moose Antler Furniture