Hello Everyone,

Following World War II until 1991, the United States engaged in a cold war with the Soviet Union. This resulted in a massive buildup of nuclear arms on both sides. Today visitors to the South Dakota Air and Space Museum near Rapid City and to Minuteman Missile Historical Site near South Dakota’s Badlands see vestiges of how our country protected itself.

SOUTH DAKOTA AIR AND SPACE MUSEUM

OUTSIDE AIR PARK

Located adjacent to Ellsworth Air Force Base, this museum gives a great overview of aviation history from World War II through the present day. The National Museum of the United States Air Force owns all the exhibits. Staffed by volunteers, it is regarded as the state’s aerospace museum.

The outdoor air park is filled with World War II, Korean, Vietnamese, Cold War, and present day aircraft. You can get close to 25 planes including the currently flown B-1B Lancer. Besides aircraft, such missiles are displayed as a Martin Titan I, Bell Labs NIKE-Ajax, and the Boeing Minuteman II.

A B-25 Mitchell bomber is displayed. These were used in the Doolittle Raid in April 1942 when sixteen of them took off from an aircraft carrier in the Pacific Ocean to bomb Tokyo and other targets then land in China. This mission lifted the morale of Americans after Pearl Harbor and the fall of the Philippines. Crews for this raid were selected from four squadrons at Columbia Army Air Field in South Carolina. Today, two of these squadrons are based at Ellsworth.

The VB-25J Mitchell was General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s personal plane in 1944 and 1945. He traveled frequently on this aircraft to meet with other leaders, to visit troops at the front, and during the Normandy Invasion. The bomber’s weapons were removed to make room for seating and bunks, a fold-down table, and electronics for communication and navigation. It was bulletproofed and had extra fuel tanks. The windows added, during the time he used it, still remain as does the desk he used.

The North American F-100A Super Saber was used in Vietnam. Pilots used the plane under the call sign “Misty” to fly lower and mark targets, a process usually done by much slower planes. They became known as Forward Air Controllers (FACS) and could work in areas that were too dangerous for slower planes. They used white phosphorus rockets to mark targets with smoke.

The Convair-F-102 Delta Dagger was an American plane that entered service in 1956. Its main purpose was to intercept Soviet strategic bombers during the Cold War. Crews from 23 different Air National Guard squadrons flew and maintained them between 1960 and 1977.

Though small, compared to the B-1 bomber, the Corsair II A-7D had many of the same characteristics. It could stay up a long time without refueling, carried lots of bombs, and dropped them with great accuracy. Each of them carried the same load as three World War II B-25's. They usually returned their pilots home safely. In 12,928 Vietnamese combat missions, only four A-7Ds were lost. That was amazing since they flew close to enemy troops while supporting ground troops.

The C-45 Expedition was considered a jack-of-all-trades. Variants of this airplane trained 90% of our navigators and bombardiers in World War II, carried cameras, and hauled light passengers and cargo. This museum’s plane was built in 1942 as an AT-11 Kansas with a glass nose filled with a bombsight to simulate a bomber. It was remanufactured in 1952, without its glass nose, as a C-45H for light transport duty.

Ten years into the Cold War, Ellsworth Air Force Base had the nation’s most effective heavy bombers. To protect the base, the United States Army installed around it a shield of anti-aircraft missiles - Bell Labs NIKE-Ajaxes. A NIKE launch crew had 44 members. However, dozens of soldiers and technicians were on the site.

The four hangars where the museum is located formed a complex near the Ellsworth Air Force Base runway. It had crews and jet fighters of the 54th Fighter-interceptor squadron. During the Cold War, Soviet bombers along our Arctic border probed American and Canadian air space. When an alarm sounded, pilots rushed from their quarters and taxied straight out of the hangar for takeoff.

INSIDE

Inside the two hangars are a variety of exhibits. Displays are a combination of artifacts, photographs, maps, memorabilia, videos, and dioramas. These cover the Cold War, aerospace technology, and the history of Ellsworth Air Force Base. The Aviation Hall of Fame recognizes South Dakota’s top aviation pioneers. You’ll see a simulator, a mock up of a missile control center, a navy trainer, and an army scout trainer.

The army most widely used the Vultee BT-13A Valiant as its basic trainer. It was more complex than the primary trainers used at the time. It had a more powerful engine and was faster and heavier. It required students to use two-way radio communication with the ground and operate landing flaps.

The Stinson L-5 “Sentinel” was the second most widely used Army Air Force liaison aircraft. Unarmed ones with short field takeoff and landing capability were used for reconnaissance, removing litter patients from front line areas, and delivering supplies to isolated units. They also laid communications wire, spotted enemy targets for attack aircraft, and transported personnel to remote areas. They served as light bombers in Asia and the Pacific remaining in service as late as 1955.

In the Cold War area, an AGM-28A “Hound Dog” is on display. It was an air-to-ground supersonic nuclear missile designed to destroy heavily defended ground targets. They were carried under each wing of a modified B-52 bomber. It was typically launched at 45,000 feet, climbed to over 56,000 feet, cruised to the target area, and dove to detonate. Between 1950-1963, North American Aviation built approximately 700 of these missiles. The last was removed from the Air Force inventory in 1978. They were nicknamed after Elvis Presley’s hit song “Hound Dog.”

Visitors also see an F-106 interactive aircraft cockpit and an F-16 interactive aircraft cockpit. A space gallery displays U.S. space flight and rocketry history from the Titan through the Saturn V. Look for the Lansat satellite hanging from the ceiling and the Bell helicopter in back.

ELLSWORTH AIR FORCE BASE HISTORY

The museum was the site of the community airport in 1942. When the air force was created in 1947, it was renamed Rapid City Air Force Base. In 1948, it was changed to General Weaver Air Force Base for six months before regaining its name Rapid City Air Force Base.

Originally, it was a center to train crews of bombers - the first B-17 flying fortresses. In later decades, the arsenal included the B-29 Superfortress, B-36 Peacemaker, the B-52 Stratofortress, and the B-1B Lancer. From the 1960s to the 1990s, the KC-135 tankers and EC-135 airborne command post aircraft were also stationed at this base.

With the Berlin airlift in 1948-1949, candy became a major morale booster. Allied aircraft crews, that included Lt. Colonel Chuck Childs of Rapid City, delivered food and supplies. Approaching Tempelhog Airport, Americans dropped parachutes bearing chocolate and other candy upon Berlin’s children. The aviators became known as “Candy Bombers” delivering 23 tons of sweets donated by American children and candy companies.

In 1953, an RB-36 Peacemaker bomber was testing the air defense system, flying at night at an extremely low altitude off the coast of Maine. The plane had 28 on board while it was designed for 24 people. They weren’t using a navigation system. Their incorrect calculations blew the plane off 20 miles to the northeast. The plane crashed into a hill near Nut Cove, Newfoundland. General Richard E. Ellsworth was on board. All were killed. President Eisenhower renamed Rapid City Air Force Base in 1953 to honor the general.

In the 1960s, Ellsworth housed the 44th Strategic Mission under the Strategic Air Command (SAC). It was home base for all missile launch crews as well as maintenance and support staff within the 66th, 67th, and 68th strategic missile squadrons. The 44th mission was deactivated in 1994 along with other SAC facilities due to the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START) of 1991 between the Soviet Union and the United States.

Four other air force bases were also involved with missiles in the early 60's. These were located at Minot, North Dakota; Malstrom, Montana; Cheyenne, Wyoming; and Grand Forks, North Dakota.

Ellsworth is still inspected periodically by Russian officials to confirm compliance with the treaty. U.S. officials also inspect Russian bases under the theory of “Trust but Verify.”

Approximately 3,000 people are stationed here. The base is the home of the systemwide Air Force Financial Center. Pilots fly drones out of here.

DETAILS

The museum is located seven miles east of Rapid City on Interstate I-90 just outside the entrance to Ellsworth Air Force Base. Its address is 2890 Rushmore Drive, Ellsworth AFB. The telephone number is (605) 385-5189.

Admission is free. From Memorial Day through Labor Day, the hours are 8:30 a.m. to 6:30 p.m. daily. Hours the rest of the year are 9:00 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Closed on Sundays.

TOURING A MINUTEMAN II SILO

You can visit the Ellsworth Air Force Base Minuteman II missile site. It’s the only Minuteman II silo in the nation allowing the public inside the structure. It was used to train crews between the 1960s and the 1990s to install missiles into silos and to maintain them. The silo includes an inert missile.

No bags of any size are permitted and it is essential to have a VALID ID such as a driver’s license or a passport. A security stop is made at the Ellsworth Air Force Base Visitor Center. The tour is only available to U.S. citizens and resident aliens.

Tours leave from the museum and are on a first-come, first-serve basis. They take from an hour to an hour-and-a-half. Four tours are given each day Monday through Friday from mid-May to mid-September. They’re scheduled at 9:15 a.m., 11:15 a.m., 12:15 p.m., and 2:15 p.m. Bus tours are $10 for adults, $7 for children ages 11-17, and $5 for children ages five to ten.

TOPSIDE

The major part of your time will be spent at the missile training site. Your tour guide will explain about the three vehicles in the parking lot before you head inside to see the actual missile.

These vehicles were part of a slow convoy, going 40 mph between Ellsworth and the missile control centers, twice a week, to bring missiles for maintenance. Private security forces traveled in front while the sheriff’s department or state police followed. A Huey helicopter escorted the entire team. It was a three-day operation - one day over, one day back, and one day at Ellsworth.

The black van, called the Beast Keeper, was used by the security force to reach the silo within minutes. It’s an armored vehicle on a Dodge pickup frame. Ellsworth was the only base to use these vehicles as all other bases used Dodge pickup trucks for their security forces.

The large 80-foot semi truck on the site was one of five that transported the propellant stages of the missile. They were brought to the site, a trap door opened at the trailer’s bottom, the missile stood up at a 90-degree angle, and then downloaded into the silo. Propellant stages were 46 feet long. They built the truck that size because they anticipated the next generation of missiles to be larger. However, Minuteman II and III fit well inside.

The truck was kept at 55 degrees and 15 percent humidity which was ideal for the solid rocket fuel. If the propellant became too hot, it had the consistency of a wax candle. If it was too cold, it would crack. If the truck temperature would not stabilize, an ancillary environmental unit was used.

GM built the tractor while Seth constructed the trailer. It had a V12 gasoline engine, shag carpet in the cab which acted to deaden sound, and very little suspension since it was built low to the ground. In the early 60s when these vehicles were built, not a lot of cars had air conditioning. The government took the Pontiac’s air conditioning and adapted it to the truck.

After the missile was in place, staff brought the guidance system and warheads forward in an electronic control van. They then downloaded those on top of the missile. A skirt on the vehicle kept the weather out when they had the door open and kept the Russian satellite from spying on the crew when they worked inside the van.

Your guide will point out that you are standing on the silo door consisting of 80 tons of concrete. It could tolerate anything but a direct hit from another missile. When the crew wanted to open this door so they could get the missile in and out of the silo, they had to crank it with a jack which took up to an hour. There was no motor on the door.

During a launch, they would want the door off quickly. Down below there are tanks and a cable system that would throw this door off in three seconds. On one of the earlier launches there was a problem. The door went through the fence behind the property ripping the barrier up. This fouled the launch. The fence now breaks away at the end of the property.

You’ll also see a tall white pole. It’s an antenna to communicate with the flying command post if the air force wanted to launch a missile from an aircraft. The top of the pole is a motion detector and was the only security they had on this site. The whole area was under motion detection. Jackrabbits caused a lot of false alarms as did people who came to the fence to look at the site.

DOWNSTAIRS

The tour now enters the silo and heads down two flights of stairs. The silo is 80 feet long while the missile is only 56-foot long leaving a large gap underneath. This was done because the structure was designed for a Minuteman I missile. They expected that Minuteman II would be longer. A Minuteman II is in the silo now.

Active silos were located anywhere from five to ten miles away from a launch control center. You can visit one of each of these and a visitor center at Minuteman National Historic Site It is located about 50 miles from Ellsworth Air Force Base and will be covered in part two of this article.

The missile is in three parts. The white part is its guidance system. Right above the green ring is where the warhead was connected. It was a single 1.2 megaton warhead, 25 times more powerful than what we dropped on Hiroshima. The green section was full of solid rocket fuel in three propellant stages. It could travel 7,000 miles at 15,000 mph. From the time it launched to when it reached the target was about 15 minutes.

Each missile had a specific target. By using Celestial navigation via the North Star, the location of where the missile was in South Dakota and where it was going in the world could be determined. This could take up to 24 hours depending on the earth’s rotation and the star system. Once the coordinates were in the missile, it was ready to go at a moment’s notice. With all of the 150 missiles, once the targets were determined, unless there was a strategic change, they were highly unlikely to change.

Minuteman III missiles use GPS and computers. They are active within a matter of seconds. Cheyenne, Wyoming; Malstrom, Montana; and Minot, North Dakota have a total of 450 of these missiles today. At the height of the Cold War, there were twelve hundred missiles in silos throughout the United States.

MAINTENANCE OF MISSILES

No actual maintenance was done outside in the field where the missiles were stored. They were always brought back to Ellsworth Air Force Base. Two teams came out. One removed the guidance system and the warhead. The second crew removed the repellant stages. They would come out in the separate vehicles mentioned above. At no time was the missile transported whole for safety reasons.

The maintenance cage will be pointed out to you. It was not normally inside the silo but was something the maintenance crew would bring with them. Once the cage was in place and safety lines attached, the cage could go 360 degrees around the silo all the way to the bottom. This provided access to any point in the missile.

Once the propellant stages were in place, they were serviced at Ellsworth but not replaced. The crew took the guidance system and warhead off and brought it back to Ellsworth Air Force Base to make sure all the guidance systems were working properly. These ran continuously and were kept programmed and ready to go. The crew checked the systems out and replaced whatever parts these needed.

Your guide will also point out a concrete hatch. It was a security device that prevented anyone from getting into the silo. This was the only way in and out of the silo outside of operating that heavy concrete door. Since the door could take an hour to reach the fully opened position, all people and equipment came down via this plug.

PROJECT

In South Dakota, the entire missile project consisted of constructing 150 silos and 15 launch facilities in the western portion of the state. Each launch control facility was responsible for 10 missiles. It cost $300 million to build with missiles priced at a million dollars apiece.

In 1991 the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty between President George W. Bush and Mikhail Gorbachev led to Minuteman missile units beginning to shut down. The last missiles in South Dakota were removed and the 44th Strategic Mission under SAC inactivated in 1994.

Today, where these missile sites once were, you can see patches of land surrounded by fences that had encircled these silos. The government returned the land to ranchers but did not include any money to remove these enclosures. They left this up to the ranchers. The concrete for them goes down about eight feet for each post while the fence goes three feet below the ground. It’s a giant operation to get these fences down.

Landowners are restricted from digging down more than two feet for two reasons. The Russians want to put a satellite over the area and make sure the United Sates is not digging a silo again. PCP contaminants from the cabling that blew off from the silos are found below the soil. Unfortunately, this makes this land useless.

In part two, readers will visit Minuteman Missile Historical Site to learn about a site housing another missile in a silo and take a tour of a former underground launch control center. They’ll also visit a visitor center at the historical site with extensive exhibits on all aspects of this arms race.

Following World War II until 1991, the United States engaged in a cold war with the Soviet Union. This resulted in a massive buildup of nuclear arms on both sides. Today visitors to the South Dakota Air and Space Museum near Rapid City and to Minuteman Missile Historical Site near South Dakota’s Badlands see vestiges of how our country protected itself.

SOUTH DAKOTA AIR AND SPACE MUSEUM

OUTSIDE AIR PARK

Located adjacent to Ellsworth Air Force Base, this museum gives a great overview of aviation history from World War II through the present day. The National Museum of the United States Air Force owns all the exhibits. Staffed by volunteers, it is regarded as the state’s aerospace museum.

The outdoor air park is filled with World War II, Korean, Vietnamese, Cold War, and present day aircraft. You can get close to 25 planes including the currently flown B-1B Lancer. Besides aircraft, such missiles are displayed as a Martin Titan I, Bell Labs NIKE-Ajax, and the Boeing Minuteman II.

A B-25 Mitchell bomber is displayed. These were used in the Doolittle Raid in April 1942 when sixteen of them took off from an aircraft carrier in the Pacific Ocean to bomb Tokyo and other targets then land in China. This mission lifted the morale of Americans after Pearl Harbor and the fall of the Philippines. Crews for this raid were selected from four squadrons at Columbia Army Air Field in South Carolina. Today, two of these squadrons are based at Ellsworth.

The VB-25J Mitchell was General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s personal plane in 1944 and 1945. He traveled frequently on this aircraft to meet with other leaders, to visit troops at the front, and during the Normandy Invasion. The bomber’s weapons were removed to make room for seating and bunks, a fold-down table, and electronics for communication and navigation. It was bulletproofed and had extra fuel tanks. The windows added, during the time he used it, still remain as does the desk he used.

The North American F-100A Super Saber was used in Vietnam. Pilots used the plane under the call sign “Misty” to fly lower and mark targets, a process usually done by much slower planes. They became known as Forward Air Controllers (FACS) and could work in areas that were too dangerous for slower planes. They used white phosphorus rockets to mark targets with smoke.

The Convair-F-102 Delta Dagger was an American plane that entered service in 1956. Its main purpose was to intercept Soviet strategic bombers during the Cold War. Crews from 23 different Air National Guard squadrons flew and maintained them between 1960 and 1977.

Though small, compared to the B-1 bomber, the Corsair II A-7D had many of the same characteristics. It could stay up a long time without refueling, carried lots of bombs, and dropped them with great accuracy. Each of them carried the same load as three World War II B-25's. They usually returned their pilots home safely. In 12,928 Vietnamese combat missions, only four A-7Ds were lost. That was amazing since they flew close to enemy troops while supporting ground troops.

The C-45 Expedition was considered a jack-of-all-trades. Variants of this airplane trained 90% of our navigators and bombardiers in World War II, carried cameras, and hauled light passengers and cargo. This museum’s plane was built in 1942 as an AT-11 Kansas with a glass nose filled with a bombsight to simulate a bomber. It was remanufactured in 1952, without its glass nose, as a C-45H for light transport duty.

Ten years into the Cold War, Ellsworth Air Force Base had the nation’s most effective heavy bombers. To protect the base, the United States Army installed around it a shield of anti-aircraft missiles - Bell Labs NIKE-Ajaxes. A NIKE launch crew had 44 members. However, dozens of soldiers and technicians were on the site.

The four hangars where the museum is located formed a complex near the Ellsworth Air Force Base runway. It had crews and jet fighters of the 54th Fighter-interceptor squadron. During the Cold War, Soviet bombers along our Arctic border probed American and Canadian air space. When an alarm sounded, pilots rushed from their quarters and taxied straight out of the hangar for takeoff.

INSIDE

Inside the two hangars are a variety of exhibits. Displays are a combination of artifacts, photographs, maps, memorabilia, videos, and dioramas. These cover the Cold War, aerospace technology, and the history of Ellsworth Air Force Base. The Aviation Hall of Fame recognizes South Dakota’s top aviation pioneers. You’ll see a simulator, a mock up of a missile control center, a navy trainer, and an army scout trainer.

The army most widely used the Vultee BT-13A Valiant as its basic trainer. It was more complex than the primary trainers used at the time. It had a more powerful engine and was faster and heavier. It required students to use two-way radio communication with the ground and operate landing flaps.

The Stinson L-5 “Sentinel” was the second most widely used Army Air Force liaison aircraft. Unarmed ones with short field takeoff and landing capability were used for reconnaissance, removing litter patients from front line areas, and delivering supplies to isolated units. They also laid communications wire, spotted enemy targets for attack aircraft, and transported personnel to remote areas. They served as light bombers in Asia and the Pacific remaining in service as late as 1955.

In the Cold War area, an AGM-28A “Hound Dog” is on display. It was an air-to-ground supersonic nuclear missile designed to destroy heavily defended ground targets. They were carried under each wing of a modified B-52 bomber. It was typically launched at 45,000 feet, climbed to over 56,000 feet, cruised to the target area, and dove to detonate. Between 1950-1963, North American Aviation built approximately 700 of these missiles. The last was removed from the Air Force inventory in 1978. They were nicknamed after Elvis Presley’s hit song “Hound Dog.”

Visitors also see an F-106 interactive aircraft cockpit and an F-16 interactive aircraft cockpit. A space gallery displays U.S. space flight and rocketry history from the Titan through the Saturn V. Look for the Lansat satellite hanging from the ceiling and the Bell helicopter in back.

ELLSWORTH AIR FORCE BASE HISTORY

The museum was the site of the community airport in 1942. When the air force was created in 1947, it was renamed Rapid City Air Force Base. In 1948, it was changed to General Weaver Air Force Base for six months before regaining its name Rapid City Air Force Base.

Originally, it was a center to train crews of bombers - the first B-17 flying fortresses. In later decades, the arsenal included the B-29 Superfortress, B-36 Peacemaker, the B-52 Stratofortress, and the B-1B Lancer. From the 1960s to the 1990s, the KC-135 tankers and EC-135 airborne command post aircraft were also stationed at this base.

With the Berlin airlift in 1948-1949, candy became a major morale booster. Allied aircraft crews, that included Lt. Colonel Chuck Childs of Rapid City, delivered food and supplies. Approaching Tempelhog Airport, Americans dropped parachutes bearing chocolate and other candy upon Berlin’s children. The aviators became known as “Candy Bombers” delivering 23 tons of sweets donated by American children and candy companies.

In 1953, an RB-36 Peacemaker bomber was testing the air defense system, flying at night at an extremely low altitude off the coast of Maine. The plane had 28 on board while it was designed for 24 people. They weren’t using a navigation system. Their incorrect calculations blew the plane off 20 miles to the northeast. The plane crashed into a hill near Nut Cove, Newfoundland. General Richard E. Ellsworth was on board. All were killed. President Eisenhower renamed Rapid City Air Force Base in 1953 to honor the general.

In the 1960s, Ellsworth housed the 44th Strategic Mission under the Strategic Air Command (SAC). It was home base for all missile launch crews as well as maintenance and support staff within the 66th, 67th, and 68th strategic missile squadrons. The 44th mission was deactivated in 1994 along with other SAC facilities due to the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START) of 1991 between the Soviet Union and the United States.

Four other air force bases were also involved with missiles in the early 60's. These were located at Minot, North Dakota; Malstrom, Montana; Cheyenne, Wyoming; and Grand Forks, North Dakota.

Ellsworth is still inspected periodically by Russian officials to confirm compliance with the treaty. U.S. officials also inspect Russian bases under the theory of “Trust but Verify.”

Approximately 3,000 people are stationed here. The base is the home of the systemwide Air Force Financial Center. Pilots fly drones out of here.

DETAILS

The museum is located seven miles east of Rapid City on Interstate I-90 just outside the entrance to Ellsworth Air Force Base. Its address is 2890 Rushmore Drive, Ellsworth AFB. The telephone number is (605) 385-5189.

Admission is free. From Memorial Day through Labor Day, the hours are 8:30 a.m. to 6:30 p.m. daily. Hours the rest of the year are 9:00 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Closed on Sundays.

TOURING A MINUTEMAN II SILO

You can visit the Ellsworth Air Force Base Minuteman II missile site. It’s the only Minuteman II silo in the nation allowing the public inside the structure. It was used to train crews between the 1960s and the 1990s to install missiles into silos and to maintain them. The silo includes an inert missile.

No bags of any size are permitted and it is essential to have a VALID ID such as a driver’s license or a passport. A security stop is made at the Ellsworth Air Force Base Visitor Center. The tour is only available to U.S. citizens and resident aliens.

Tours leave from the museum and are on a first-come, first-serve basis. They take from an hour to an hour-and-a-half. Four tours are given each day Monday through Friday from mid-May to mid-September. They’re scheduled at 9:15 a.m., 11:15 a.m., 12:15 p.m., and 2:15 p.m. Bus tours are $10 for adults, $7 for children ages 11-17, and $5 for children ages five to ten.

TOPSIDE

The major part of your time will be spent at the missile training site. Your tour guide will explain about the three vehicles in the parking lot before you head inside to see the actual missile.

These vehicles were part of a slow convoy, going 40 mph between Ellsworth and the missile control centers, twice a week, to bring missiles for maintenance. Private security forces traveled in front while the sheriff’s department or state police followed. A Huey helicopter escorted the entire team. It was a three-day operation - one day over, one day back, and one day at Ellsworth.

The black van, called the Beast Keeper, was used by the security force to reach the silo within minutes. It’s an armored vehicle on a Dodge pickup frame. Ellsworth was the only base to use these vehicles as all other bases used Dodge pickup trucks for their security forces.

The large 80-foot semi truck on the site was one of five that transported the propellant stages of the missile. They were brought to the site, a trap door opened at the trailer’s bottom, the missile stood up at a 90-degree angle, and then downloaded into the silo. Propellant stages were 46 feet long. They built the truck that size because they anticipated the next generation of missiles to be larger. However, Minuteman II and III fit well inside.

The truck was kept at 55 degrees and 15 percent humidity which was ideal for the solid rocket fuel. If the propellant became too hot, it had the consistency of a wax candle. If it was too cold, it would crack. If the truck temperature would not stabilize, an ancillary environmental unit was used.

GM built the tractor while Seth constructed the trailer. It had a V12 gasoline engine, shag carpet in the cab which acted to deaden sound, and very little suspension since it was built low to the ground. In the early 60s when these vehicles were built, not a lot of cars had air conditioning. The government took the Pontiac’s air conditioning and adapted it to the truck.

After the missile was in place, staff brought the guidance system and warheads forward in an electronic control van. They then downloaded those on top of the missile. A skirt on the vehicle kept the weather out when they had the door open and kept the Russian satellite from spying on the crew when they worked inside the van.

Your guide will point out that you are standing on the silo door consisting of 80 tons of concrete. It could tolerate anything but a direct hit from another missile. When the crew wanted to open this door so they could get the missile in and out of the silo, they had to crank it with a jack which took up to an hour. There was no motor on the door.

During a launch, they would want the door off quickly. Down below there are tanks and a cable system that would throw this door off in three seconds. On one of the earlier launches there was a problem. The door went through the fence behind the property ripping the barrier up. This fouled the launch. The fence now breaks away at the end of the property.

You’ll also see a tall white pole. It’s an antenna to communicate with the flying command post if the air force wanted to launch a missile from an aircraft. The top of the pole is a motion detector and was the only security they had on this site. The whole area was under motion detection. Jackrabbits caused a lot of false alarms as did people who came to the fence to look at the site.

DOWNSTAIRS

The tour now enters the silo and heads down two flights of stairs. The silo is 80 feet long while the missile is only 56-foot long leaving a large gap underneath. This was done because the structure was designed for a Minuteman I missile. They expected that Minuteman II would be longer. A Minuteman II is in the silo now.

Active silos were located anywhere from five to ten miles away from a launch control center. You can visit one of each of these and a visitor center at Minuteman National Historic Site It is located about 50 miles from Ellsworth Air Force Base and will be covered in part two of this article.

The missile is in three parts. The white part is its guidance system. Right above the green ring is where the warhead was connected. It was a single 1.2 megaton warhead, 25 times more powerful than what we dropped on Hiroshima. The green section was full of solid rocket fuel in three propellant stages. It could travel 7,000 miles at 15,000 mph. From the time it launched to when it reached the target was about 15 minutes.

Each missile had a specific target. By using Celestial navigation via the North Star, the location of where the missile was in South Dakota and where it was going in the world could be determined. This could take up to 24 hours depending on the earth’s rotation and the star system. Once the coordinates were in the missile, it was ready to go at a moment’s notice. With all of the 150 missiles, once the targets were determined, unless there was a strategic change, they were highly unlikely to change.

Minuteman III missiles use GPS and computers. They are active within a matter of seconds. Cheyenne, Wyoming; Malstrom, Montana; and Minot, North Dakota have a total of 450 of these missiles today. At the height of the Cold War, there were twelve hundred missiles in silos throughout the United States.

MAINTENANCE OF MISSILES

No actual maintenance was done outside in the field where the missiles were stored. They were always brought back to Ellsworth Air Force Base. Two teams came out. One removed the guidance system and the warhead. The second crew removed the repellant stages. They would come out in the separate vehicles mentioned above. At no time was the missile transported whole for safety reasons.

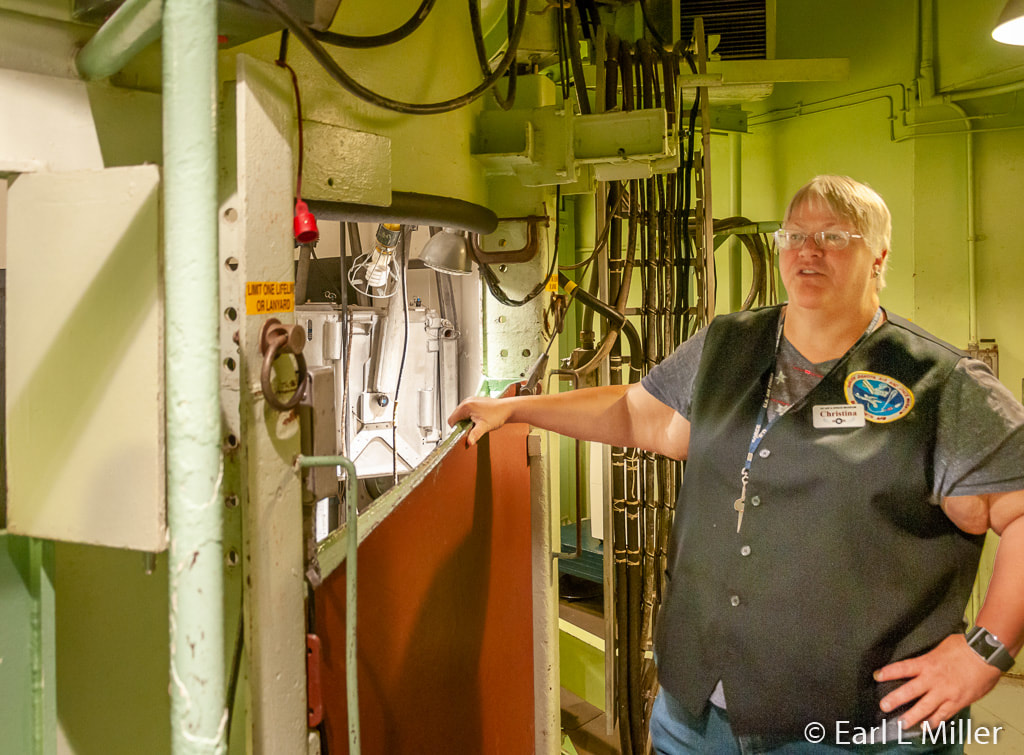

The maintenance cage will be pointed out to you. It was not normally inside the silo but was something the maintenance crew would bring with them. Once the cage was in place and safety lines attached, the cage could go 360 degrees around the silo all the way to the bottom. This provided access to any point in the missile.

Once the propellant stages were in place, they were serviced at Ellsworth but not replaced. The crew took the guidance system and warhead off and brought it back to Ellsworth Air Force Base to make sure all the guidance systems were working properly. These ran continuously and were kept programmed and ready to go. The crew checked the systems out and replaced whatever parts these needed.

Your guide will also point out a concrete hatch. It was a security device that prevented anyone from getting into the silo. This was the only way in and out of the silo outside of operating that heavy concrete door. Since the door could take an hour to reach the fully opened position, all people and equipment came down via this plug.

PROJECT

In South Dakota, the entire missile project consisted of constructing 150 silos and 15 launch facilities in the western portion of the state. Each launch control facility was responsible for 10 missiles. It cost $300 million to build with missiles priced at a million dollars apiece.

In 1991 the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty between President George W. Bush and Mikhail Gorbachev led to Minuteman missile units beginning to shut down. The last missiles in South Dakota were removed and the 44th Strategic Mission under SAC inactivated in 1994.

Today, where these missile sites once were, you can see patches of land surrounded by fences that had encircled these silos. The government returned the land to ranchers but did not include any money to remove these enclosures. They left this up to the ranchers. The concrete for them goes down about eight feet for each post while the fence goes three feet below the ground. It’s a giant operation to get these fences down.

Landowners are restricted from digging down more than two feet for two reasons. The Russians want to put a satellite over the area and make sure the United Sates is not digging a silo again. PCP contaminants from the cabling that blew off from the silos are found below the soil. Unfortunately, this makes this land useless.

In part two, readers will visit Minuteman Missile Historical Site to learn about a site housing another missile in a silo and take a tour of a former underground launch control center. They’ll also visit a visitor center at the historical site with extensive exhibits on all aspects of this arms race.

Approaching the South Dakota Air and Space Museum

South Dakota Air and Space Museum's Entrance

B-25 Mitchell Bomber - Eisenhower's Personal Plane

Convair C-131D Samaritan

North American F-100A Super Saber

Convair-F-102 Delta Dagger

Corsair II A-7D

C-45 Expedition

Bell Labs NIKE-Ajax Missile

Korean War Artifacts

Vultee BT-13A Valiant

Stinson L-5 “Sentinel”

Bell Helicopter

AGM-28A “Hound Dog”

B-52 Stratofortress

The Beast Keeper

Transported the Propellant Part of the Missile

Transported the Guidance System and Warheads

From Top to Bottom - Warhead, Guidance System, Missile Propellant Area

Our Guide Christina Campbell Demonstrating The Maintenance Area

Maintenance Cage from the Other Side - How Propellant was Added to the Missile

The Escape Route Out of the Silo