Hello Everyone,

Fans of dinosaurs, fossils, rocks, and minerals have two fascinating Black Hills attractions to visit. The Black Hills Institute of Geological Research’s Museum of Natural History in Hill City is loaded with numerous types of fossils, dinosaurs, and many geological specimens. At Rapid City’s Museum of Geology, located at South Dakota School of Mines & Technology, visitors see one area filled with fossils and casts and another containing beautiful ores and minerals from all over the Earth.

BLACK HILLS INSTITUTE OF GEOLOGICAL RESEARCH, INC.

HISTORY

BHI is the largest private corporation in the world specializing in the excavation and preparation of fossils including major dinosaur skeletons. The company’s primary business is supplying professionally prepared fossils, fossil casts, mineral specimens, and related information for research, teaching, and exhibit. These range from the largest dinosaurs to small fossils and mineral collectibles. Their cast replicas are displayed in museums and science centers, zoos and aquariums, and even shopping centers and private homes.

Founded in 1974, it is most famous for excavating and selling replicas of some of the most famous tyrannosaurus rex. “Sue,” the most complete T-rex, is now housed at Chicago’s Field Museum. Visitors can see “Stan,” the second most complete T-rex, at the Institute’s Black Hills Museum of Natural History founded in 1992.

We had the pleasure of meeting Peter Larson, who is president of BHI. He grew up on a ranch near Mission, South Dakota and started rock hunting at age four on his parents’ ranch. He graduated in 1974 from the South Dakota School of Mines with a degree in geology. Later that year, he started the company eventually known as Black Hills Institute of Geological Research, Inc.

Between 1985 and 1990, he collected specimens in Peru as well as fossils in Germany, Switzerland, and England. However, most of the museum’s collection comes from South Dakota, Montana, Wyoming, and Nebraska.

His partners, Bob Farrar and his brother, Neal Larson, joined the company in 1978. Neal left his position in 2018. Peter has written and coauthored many publications on dinosaurs and excavated more T-rex’s than any other paleontologist in the world. In 1990, Peter led the excavation of the T-rex skeleton “Sue.” In 1992, his team helped discover the T-rex named “Stan.” He led colleagues in 2013 to an excavation site in Wyoming where they found remnants of three nearly complete triceratops skeletons.

Another paleontology area for which the Institute has gained attention is in Upper Cretaceous ammonites, an abundant fossil marine invertebrate. Neal Larson has achieved fame as one of the world's premier scientists in the study and identification of these animals and still works on them today.

Bob Farrar’s expertise is in mineralogy. Because of him, the Institute has been able to collect numerous rare minerals, bringing BHI to the attention of mineralogists around the world. Bob and Pete have collaborated with German, Canadian and American researchers, especially in the study of pegmatite phosphate minerals that are native to the Black Hills of South Dakota.

While searching for fossils in South Dakota, the men also developed an interest in local Fairburn agates. Their museum has a wonderful selection of this kind of specimen.

Peter said, “When we collect a fossil like the T-rex, it is important to collect all the plants and animals found at the same site. This helps to reconstruct what was going on at that time in history.”

THE WORK THEY DO

BHI has collected vertebrate and invertebrate fossils in many locations in the United States and globally. Besides dinosaurs, they have discovered reptiles, lizards, and bird fossil specimens. They have uncovered dinosaur skin, brain tumors, and other anatomical features. Besides collecting, they also consult in fossil identification, preservation, restoration, and display.

Their facility houses what they tout as the world’s most extensive research collection of T-rex fossil material. This material and their enormous fossil collection are always available to visiting researchers.

In the United States, their work is seen at such museums as Chicago’s Field Museum; the Smithsonian Natural History Museum in Washington, D.C.; Denver’s Museum of Natural Science; The Los Angeles Museum of Natural History; the Children’s Museum in Indianapolis; the Houston Museum of Natural Science; and the Museum of the Rockies in Bozeman, Montana.

Their work is also displayed at museums worldwide. Some of the places you can see their original fossils and cast reproductions are Tokyo’s National Science Museum; the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Paleontology in Drumheller, Alberta, Canada; the National Museum of Natural History in Leiden, Netherlands; and the National Museum of Wales in Cardiff, Wales.

To see the extent of their work, go to the web site catalog page. It includes original fossils, cast replicas (teeth, claws, and skulls to complete skeletons), educational materials such as books and videos, and fossil collecting and preparation tools and supplies.

HOW IT IS CAST

When Earl and I visited BHI last year, Peter gave us a complete tour of the facility. In another building, not normally open to visitors, we were able to see the complex process they undergo preparing casts and fossils. When we were there, they were working on the acrocanthosaurus’s lower jaw. It was a large dinosaur found in Oklahoma and is now at the Raleigh, North Carolina State Museum.

The process starts with finding and digging up the fossil. Then it is cleaned and stabilized. The company prepares vertebrate and invertebrate fossils.

They then restore the missing bones and missing pieces of bones or parts. BHI’s staff has developed new methods and materials for molding fossils and producing cast replicas which retain the look and feel of the original fossils. Sometimes bones have to be made from scratch, created by sculpting. At other times, BHI can use casts from other skeletons. When they have only one of a species, what they produce is based on what the fossil’s relatives were like.

Because each bone is unique, it is important to record the information presented by those bones. Thus BHI creates molds and casts of some of those specimens. Molds are made of silicon that faithfully preserve the details of each fossil. Liquid polyurethane is poured into the molds to produce casts of the fossils. When the polyurethane hardens, the casts become scientific replicas with all the measurements and details of the original fossil. Sometimes BHI works with a foundry to make bronze replicas for indoors or outside.

After they make the casts, they can mount entire skeletons. BHI has become the industry leader in creating displays that are easy to transport and assemble. This is accomplished via their modular, freestanding method to mount real and cast large vertebrate skeletons. For example, four people can assemble a full T-rex skeleton in just over an hour. More complicated specimens come with installation instructions.

BHI puts steel inside the cast parts and steel outside on the original fossils. When you tour their museum, this is the way to tell casts from original fossils. If you see a lot of steel supports, you are looking at an original skeleton.

To paint the cast, a base coat of enamel paint is first used. Acrylic paints are used for the exterior coat in order to match the colors with the original bone. Original bones are not painted but all cast bones are.

WHAT VISITORS SEE

Although the floor space devoted to BHI’s Museum of Natural History is modest, the number of specimens visitors see is not. According to AAA, their collection includes more than 900 original fossils and 170 replicas as well as over 500 minerals, meteorites, and agates. On display are 9 T-rex skulls and more than 30 dinosaur skeletons. I recently called BHI and asked a staff member if these numbers were correct and was told “yes.”

Exhibits extend along the walls with the center being occupied by several big impressive dinosaur fossils. Their T-rex “Stan” is the centerpiece. Its skull is so heavy that it can’t be mounted as a cast. It was only after the bones were prepared that BHI staff realized it was the best skull of all the T-rex specimens ever collected. It was not only complete but the bones were in pristine condition.

You will also see “Duffy,” a T-rex discovered in South Dakota by Stan Sacristan. Its excavation was started in 1993. They also have a replica of the T-rex “Sue.”

They have titanothere skulls on display. This animal was related to horses and rhinoceroses. They were similar in size to today’s modern white rhino. It was the first fossil described from the Badlands region. Dr. Hiram Prout wrote about it in 1847 in the American Journal of Science.

Among the many exhibits, we saw the skeleton of a baleen whale, fish fossils, giant ammonites, a Nanotyrannus and a Torosaurus which were large dinosaurs. In cases lining the walls, we also spotted a penguin fossil, ostrich egg, Sauropod egg, duckbill dinosaur, saber-toothed tiger skull, and a crocodile skull. Fossils of animals known today include a beaver, ground squirrel, and camel. They also have skulls of man: a Neanderthal from France and the Nariokotome boy from Kenya.

They have lots of amphibian, marine, and plant fossils. Visitors see sea biscuits, echinoids, ferns, cycads, ammonites, and petrified wood. Their cycad collection is second only to Yale University.

Their minerals have been collected worldwide with a case devoted to South Dakota specimens. Others are exhibited in separate cases by topic. This includes agates, carbonates, crystallized quartz, Peruvian minerals such as pyrite, and rhodochrosite. There are also lots of agates and lapidary creations. They also have a case devoted to meteorites from all over the world.

DETAILS

The gift shop, Everything Prehistoric, is extensive and worth a look. You pass through it on your way into and out of the museum.

Black Hills Institute is located at 117 E Main Street in Hill City, South Dakota. Their telephone number is (605) 574-3919. From Memorial Day through Labor Day, hours are 9:30 a.m. to 6:30 p.m. The rest of the year, the hours are 9:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. They are closed on Sunday year round. Admission is $7.50 for adults (16 and older), $6 for seniors, veterans, and U.S. Military (must ask for discount), $4 for children ages 6-15, and free for those ages five and younger. With every paid admission, visitors receive a year-long pass. Ask BHI employees about this.

MUSEUM OF GEOLOGY

A LITTLE HISTORY

Rapid City’s Museum of Geology has been collecting and displaying specimens since 1885 when the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology was founded. The school was one of a group of land grant universities.

The first assortment, a group of rocks from the Black Hills, started the collection now consisting of half a million specimens. As the collections expanded, the museum changed locations. About 75 years ago, collections were moved to their present site on the third floor of the O’Harra Building, the campus’s main administration building, with their laboratory moved to a separate building about eight years ago. They have always taught students through field work and lab work. One of their expeditions, the Pig Dig in the Badlands, led to the discovery of 27,000 bones.

The museum is considered a leader in conserving South Dakota’s rich geology and paleontology heritage. It does this by collecting, housing, and researching the state’s, particularly the Black Hills’s rich resources, with the Middle and Late Cretaceous periods being the museum’s strengths. It is the oldest continually operated museum in South Dakota.

Today’s visitors find fascinating mounted skeletons of dinosaurs, mammals, marine reptiles, and fish in one room. That includes rare fossils from the White River Badlands with many arranged in dioramas reflecting the period when they lived. Specimens of vertebrates and invertebrates are exhibited.

The vertebrate paleontology collection consists of specimens ranging from the Ordovician through the Pleistocene periods. It’s a time frame spanning nearly 400 million years. Most specimens came from deposits of the Cretaceous Western Interior Seaway and the Eocene-Oligocene of the White River Group in the northern Great Plains.

About half of their collection belongs to others: the federal government, state of South Dakota, and tribal. They are a repository for these. The ones belonging to Native Americans have a blessing ceremony. We were told that Pine Ridge Reservation has some of the best fossils.

They have several fish fossils and ammonites including a placenticeras, octopus, and squid. You will see a plesiosaur which was a long-necked marine reptile. It had fins, swam, and ate fish.

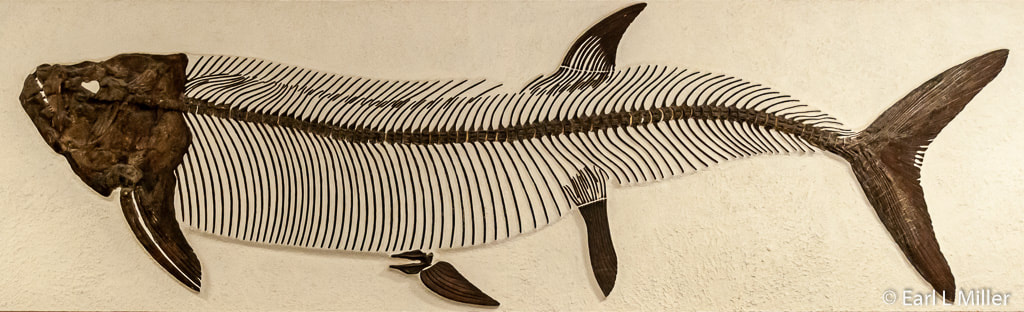

The xiphactinus audak or “Bulldog Fish” is the longest known fossil of teleosts or bony fish. The most primitive teleosts lived during the middle of the Jurassic Period, 160 million years ago. More than 20,000 species are alive today.

Their alligator fossil is similar to today’s alligator found in the southeastern United States since these animals have been around for 250 million years. This fossil’s presence in the Badlands indicates more temperate conditions previously existed in the area.

Visitors note the 29-foot mosasaurus which is a large marine lizard that existed during the Cretaceous period. They were carnivorous - dining mainly on fish and reptiles.

Dinosaurs and mammals are well represented. They have a cast of a T-rex skull whose original is at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Visitors will also see the state fossil, the triceratops horridus. The triceratops, a horned dinosaur, was one of the last major groups of dinosaurs to appear on Earth. They were common in the late Cretaceous period. Its huge head exceeded that of any other land animal. It was a herbivore that used its horn for defense.

The bronthotheres resemble rhinoceroses more than horses or tapirs but are relatives of all three groups. The museum’s skeleton is one of the very few relatively complete ones ever found. Scientists have been interested in it because it shows arthritis in its shoulder.

A Gompothetrium, which is like an elephant; a Nimravid (which looks like a saber-toothed tiger); camels; three-toed horses; and tortoises for which the Badlands are famous are also displayed. Camels were abundant in North America until near the end of the Ice Age. The one exhibited was among the earliest known. It strongly resembles the characteristics of today’s camels. The major difference was that early camels had a small stature.

We were told that their most famous fossil is the oreodont. What makes this specimen special is that this oreodont was pregnant with twins. It is the only mounted specimen of a fossil with unborn young. Some of the oreodont’s characteristics were like a pig (short, four toes) while others resembled a sheep (tooth structure). They are not closely related to any living animal.

Their invertebrate paleontology collection has specimens from nearly every type of invertebrate animals. Collections include insects, mollusks, and arthropods. The Cretaceous and Cenozoic periods are well represented.

The geological history of the horse started 55 million years ago with an animal, the hyracotherium, the size of a small dog. Its teeth and feet were much different than those of today’s horse. The museum displays the skeleton of the Mesohippus which was much smaller than the domestic horse. It had three toes rather than one hoof on its foot. Its teeth could only handle soft leaves and shoots while the modern horse’s teeth are designed to chew rough prairie grasses.

The collection of several hundred fossil plants consists primarily of Jurassic to the late Pleistocene age. Their signature specimens in this category are 120 million-year-old fossil cycads from the Dakota Sandstone near Edgemont, South Dakota. It is one of the largest collections from the former Fossil Cycad National Monument. Other fossils include leaves, seeds, and petrified wood.

MINERAL COLLECTION

Their mineral collection consists of minerals of all types and meteorites. It encompasses over 75,000 specimens collected from all over the world for more than a century. Some are from countries that have since limited the export of certain minerals. Visitors find a fluorescent mineral room and a South Dakota room displaying minerals collected in South Dakota. Some come from mines that have closed such as the Homestake Mine in Lead, South Dakota.

Visitors will see sedimentary deposits, metamorphic deposits, vein and replacement deposits, geodes, and agates. The agate is the state gem. They also have ore from the Homestake Gold Mine and signage relating the mine’s history. Rocks are classified by their chemical composition: halides, sulfosalts, oxides, carbonates, and sulfides.

A new interactive exhibit, a hand-sized seismometer box called Raspberry Shake, measures movement in real-time. It provides visitors with an understanding of where earthquakes occur, what causes them, and about the movement under their feet. The display allows visitors to jump up and down on the floor and see the seismic waves they create in real-time on a monitor. They will learn how even the smallest movement is recorded in seismic waves. It also features a collection of geographic maps of different regions of the world. The map relates how old the events are with the larger the circle around one of these earthquakes, the larger the event.

ESPECIALLY FAMILY ORIENTED

A major goal is to provide science education. They have a Kid’s Area where children can play with casts and other educational toys. It features an eight-foot fossil track activity, upgraded exhibits, and kid’s furniture.

Each week, on Thursdays at 2:00 p.m., the museum has youngsters join them for a geology or paleontology themed story. Besides reading an age appropriate book, youngsters will participate in a related activity such as coloring, drawing, or making a puzzle.

Special family events are held throughout the year. Two very popular annual events are the Dinosaur Eggstravaganza held in April. Youngsters can uncover all there is to know about dinosaurs and how paleontologists dig up fossils. The Annual Night at the Museum is a Halloween event providing a safe place for children to trick-or-treat while participating in educational games and activities. To check out what is being offered during your stay in Rapid City, check out their web site.

Tours are provided for visitors of the museum during normal business hours. These are scheduled in advance by emailing [email protected].

DETAILS

The Museum Gift Shop and Bookstore contains such items as educational toys, rock and mineral samples, and geology reference books and guides.

The Museum of Geology is located in the center of the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology. The collections and research facility are located in the Paleontology Research Laboratory and are not open for public tours. Exhibits and public programs can be found at 501 E. Saint Joseph Street. The museum telephone number is (605) 394-2467. Winter hours are Monday through Saturday 8:30 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. and during the summer Monday through Saturday from 9:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. Admission is free with donations appreciated.

Fans of dinosaurs, fossils, rocks, and minerals have two fascinating Black Hills attractions to visit. The Black Hills Institute of Geological Research’s Museum of Natural History in Hill City is loaded with numerous types of fossils, dinosaurs, and many geological specimens. At Rapid City’s Museum of Geology, located at South Dakota School of Mines & Technology, visitors see one area filled with fossils and casts and another containing beautiful ores and minerals from all over the Earth.

BLACK HILLS INSTITUTE OF GEOLOGICAL RESEARCH, INC.

HISTORY

BHI is the largest private corporation in the world specializing in the excavation and preparation of fossils including major dinosaur skeletons. The company’s primary business is supplying professionally prepared fossils, fossil casts, mineral specimens, and related information for research, teaching, and exhibit. These range from the largest dinosaurs to small fossils and mineral collectibles. Their cast replicas are displayed in museums and science centers, zoos and aquariums, and even shopping centers and private homes.

Founded in 1974, it is most famous for excavating and selling replicas of some of the most famous tyrannosaurus rex. “Sue,” the most complete T-rex, is now housed at Chicago’s Field Museum. Visitors can see “Stan,” the second most complete T-rex, at the Institute’s Black Hills Museum of Natural History founded in 1992.

We had the pleasure of meeting Peter Larson, who is president of BHI. He grew up on a ranch near Mission, South Dakota and started rock hunting at age four on his parents’ ranch. He graduated in 1974 from the South Dakota School of Mines with a degree in geology. Later that year, he started the company eventually known as Black Hills Institute of Geological Research, Inc.

Between 1985 and 1990, he collected specimens in Peru as well as fossils in Germany, Switzerland, and England. However, most of the museum’s collection comes from South Dakota, Montana, Wyoming, and Nebraska.

His partners, Bob Farrar and his brother, Neal Larson, joined the company in 1978. Neal left his position in 2018. Peter has written and coauthored many publications on dinosaurs and excavated more T-rex’s than any other paleontologist in the world. In 1990, Peter led the excavation of the T-rex skeleton “Sue.” In 1992, his team helped discover the T-rex named “Stan.” He led colleagues in 2013 to an excavation site in Wyoming where they found remnants of three nearly complete triceratops skeletons.

Another paleontology area for which the Institute has gained attention is in Upper Cretaceous ammonites, an abundant fossil marine invertebrate. Neal Larson has achieved fame as one of the world's premier scientists in the study and identification of these animals and still works on them today.

Bob Farrar’s expertise is in mineralogy. Because of him, the Institute has been able to collect numerous rare minerals, bringing BHI to the attention of mineralogists around the world. Bob and Pete have collaborated with German, Canadian and American researchers, especially in the study of pegmatite phosphate minerals that are native to the Black Hills of South Dakota.

While searching for fossils in South Dakota, the men also developed an interest in local Fairburn agates. Their museum has a wonderful selection of this kind of specimen.

Peter said, “When we collect a fossil like the T-rex, it is important to collect all the plants and animals found at the same site. This helps to reconstruct what was going on at that time in history.”

THE WORK THEY DO

BHI has collected vertebrate and invertebrate fossils in many locations in the United States and globally. Besides dinosaurs, they have discovered reptiles, lizards, and bird fossil specimens. They have uncovered dinosaur skin, brain tumors, and other anatomical features. Besides collecting, they also consult in fossil identification, preservation, restoration, and display.

Their facility houses what they tout as the world’s most extensive research collection of T-rex fossil material. This material and their enormous fossil collection are always available to visiting researchers.

In the United States, their work is seen at such museums as Chicago’s Field Museum; the Smithsonian Natural History Museum in Washington, D.C.; Denver’s Museum of Natural Science; The Los Angeles Museum of Natural History; the Children’s Museum in Indianapolis; the Houston Museum of Natural Science; and the Museum of the Rockies in Bozeman, Montana.

Their work is also displayed at museums worldwide. Some of the places you can see their original fossils and cast reproductions are Tokyo’s National Science Museum; the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Paleontology in Drumheller, Alberta, Canada; the National Museum of Natural History in Leiden, Netherlands; and the National Museum of Wales in Cardiff, Wales.

To see the extent of their work, go to the web site catalog page. It includes original fossils, cast replicas (teeth, claws, and skulls to complete skeletons), educational materials such as books and videos, and fossil collecting and preparation tools and supplies.

HOW IT IS CAST

When Earl and I visited BHI last year, Peter gave us a complete tour of the facility. In another building, not normally open to visitors, we were able to see the complex process they undergo preparing casts and fossils. When we were there, they were working on the acrocanthosaurus’s lower jaw. It was a large dinosaur found in Oklahoma and is now at the Raleigh, North Carolina State Museum.

The process starts with finding and digging up the fossil. Then it is cleaned and stabilized. The company prepares vertebrate and invertebrate fossils.

They then restore the missing bones and missing pieces of bones or parts. BHI’s staff has developed new methods and materials for molding fossils and producing cast replicas which retain the look and feel of the original fossils. Sometimes bones have to be made from scratch, created by sculpting. At other times, BHI can use casts from other skeletons. When they have only one of a species, what they produce is based on what the fossil’s relatives were like.

Because each bone is unique, it is important to record the information presented by those bones. Thus BHI creates molds and casts of some of those specimens. Molds are made of silicon that faithfully preserve the details of each fossil. Liquid polyurethane is poured into the molds to produce casts of the fossils. When the polyurethane hardens, the casts become scientific replicas with all the measurements and details of the original fossil. Sometimes BHI works with a foundry to make bronze replicas for indoors or outside.

After they make the casts, they can mount entire skeletons. BHI has become the industry leader in creating displays that are easy to transport and assemble. This is accomplished via their modular, freestanding method to mount real and cast large vertebrate skeletons. For example, four people can assemble a full T-rex skeleton in just over an hour. More complicated specimens come with installation instructions.

BHI puts steel inside the cast parts and steel outside on the original fossils. When you tour their museum, this is the way to tell casts from original fossils. If you see a lot of steel supports, you are looking at an original skeleton.

To paint the cast, a base coat of enamel paint is first used. Acrylic paints are used for the exterior coat in order to match the colors with the original bone. Original bones are not painted but all cast bones are.

WHAT VISITORS SEE

Although the floor space devoted to BHI’s Museum of Natural History is modest, the number of specimens visitors see is not. According to AAA, their collection includes more than 900 original fossils and 170 replicas as well as over 500 minerals, meteorites, and agates. On display are 9 T-rex skulls and more than 30 dinosaur skeletons. I recently called BHI and asked a staff member if these numbers were correct and was told “yes.”

Exhibits extend along the walls with the center being occupied by several big impressive dinosaur fossils. Their T-rex “Stan” is the centerpiece. Its skull is so heavy that it can’t be mounted as a cast. It was only after the bones were prepared that BHI staff realized it was the best skull of all the T-rex specimens ever collected. It was not only complete but the bones were in pristine condition.

You will also see “Duffy,” a T-rex discovered in South Dakota by Stan Sacristan. Its excavation was started in 1993. They also have a replica of the T-rex “Sue.”

They have titanothere skulls on display. This animal was related to horses and rhinoceroses. They were similar in size to today’s modern white rhino. It was the first fossil described from the Badlands region. Dr. Hiram Prout wrote about it in 1847 in the American Journal of Science.

Among the many exhibits, we saw the skeleton of a baleen whale, fish fossils, giant ammonites, a Nanotyrannus and a Torosaurus which were large dinosaurs. In cases lining the walls, we also spotted a penguin fossil, ostrich egg, Sauropod egg, duckbill dinosaur, saber-toothed tiger skull, and a crocodile skull. Fossils of animals known today include a beaver, ground squirrel, and camel. They also have skulls of man: a Neanderthal from France and the Nariokotome boy from Kenya.

They have lots of amphibian, marine, and plant fossils. Visitors see sea biscuits, echinoids, ferns, cycads, ammonites, and petrified wood. Their cycad collection is second only to Yale University.

Their minerals have been collected worldwide with a case devoted to South Dakota specimens. Others are exhibited in separate cases by topic. This includes agates, carbonates, crystallized quartz, Peruvian minerals such as pyrite, and rhodochrosite. There are also lots of agates and lapidary creations. They also have a case devoted to meteorites from all over the world.

DETAILS

The gift shop, Everything Prehistoric, is extensive and worth a look. You pass through it on your way into and out of the museum.

Black Hills Institute is located at 117 E Main Street in Hill City, South Dakota. Their telephone number is (605) 574-3919. From Memorial Day through Labor Day, hours are 9:30 a.m. to 6:30 p.m. The rest of the year, the hours are 9:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. They are closed on Sunday year round. Admission is $7.50 for adults (16 and older), $6 for seniors, veterans, and U.S. Military (must ask for discount), $4 for children ages 6-15, and free for those ages five and younger. With every paid admission, visitors receive a year-long pass. Ask BHI employees about this.

MUSEUM OF GEOLOGY

A LITTLE HISTORY

Rapid City’s Museum of Geology has been collecting and displaying specimens since 1885 when the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology was founded. The school was one of a group of land grant universities.

The first assortment, a group of rocks from the Black Hills, started the collection now consisting of half a million specimens. As the collections expanded, the museum changed locations. About 75 years ago, collections were moved to their present site on the third floor of the O’Harra Building, the campus’s main administration building, with their laboratory moved to a separate building about eight years ago. They have always taught students through field work and lab work. One of their expeditions, the Pig Dig in the Badlands, led to the discovery of 27,000 bones.

The museum is considered a leader in conserving South Dakota’s rich geology and paleontology heritage. It does this by collecting, housing, and researching the state’s, particularly the Black Hills’s rich resources, with the Middle and Late Cretaceous periods being the museum’s strengths. It is the oldest continually operated museum in South Dakota.

Today’s visitors find fascinating mounted skeletons of dinosaurs, mammals, marine reptiles, and fish in one room. That includes rare fossils from the White River Badlands with many arranged in dioramas reflecting the period when they lived. Specimens of vertebrates and invertebrates are exhibited.

The vertebrate paleontology collection consists of specimens ranging from the Ordovician through the Pleistocene periods. It’s a time frame spanning nearly 400 million years. Most specimens came from deposits of the Cretaceous Western Interior Seaway and the Eocene-Oligocene of the White River Group in the northern Great Plains.

About half of their collection belongs to others: the federal government, state of South Dakota, and tribal. They are a repository for these. The ones belonging to Native Americans have a blessing ceremony. We were told that Pine Ridge Reservation has some of the best fossils.

They have several fish fossils and ammonites including a placenticeras, octopus, and squid. You will see a plesiosaur which was a long-necked marine reptile. It had fins, swam, and ate fish.

The xiphactinus audak or “Bulldog Fish” is the longest known fossil of teleosts or bony fish. The most primitive teleosts lived during the middle of the Jurassic Period, 160 million years ago. More than 20,000 species are alive today.

Their alligator fossil is similar to today’s alligator found in the southeastern United States since these animals have been around for 250 million years. This fossil’s presence in the Badlands indicates more temperate conditions previously existed in the area.

Visitors note the 29-foot mosasaurus which is a large marine lizard that existed during the Cretaceous period. They were carnivorous - dining mainly on fish and reptiles.

Dinosaurs and mammals are well represented. They have a cast of a T-rex skull whose original is at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Visitors will also see the state fossil, the triceratops horridus. The triceratops, a horned dinosaur, was one of the last major groups of dinosaurs to appear on Earth. They were common in the late Cretaceous period. Its huge head exceeded that of any other land animal. It was a herbivore that used its horn for defense.

The bronthotheres resemble rhinoceroses more than horses or tapirs but are relatives of all three groups. The museum’s skeleton is one of the very few relatively complete ones ever found. Scientists have been interested in it because it shows arthritis in its shoulder.

A Gompothetrium, which is like an elephant; a Nimravid (which looks like a saber-toothed tiger); camels; three-toed horses; and tortoises for which the Badlands are famous are also displayed. Camels were abundant in North America until near the end of the Ice Age. The one exhibited was among the earliest known. It strongly resembles the characteristics of today’s camels. The major difference was that early camels had a small stature.

We were told that their most famous fossil is the oreodont. What makes this specimen special is that this oreodont was pregnant with twins. It is the only mounted specimen of a fossil with unborn young. Some of the oreodont’s characteristics were like a pig (short, four toes) while others resembled a sheep (tooth structure). They are not closely related to any living animal.

Their invertebrate paleontology collection has specimens from nearly every type of invertebrate animals. Collections include insects, mollusks, and arthropods. The Cretaceous and Cenozoic periods are well represented.

The geological history of the horse started 55 million years ago with an animal, the hyracotherium, the size of a small dog. Its teeth and feet were much different than those of today’s horse. The museum displays the skeleton of the Mesohippus which was much smaller than the domestic horse. It had three toes rather than one hoof on its foot. Its teeth could only handle soft leaves and shoots while the modern horse’s teeth are designed to chew rough prairie grasses.

The collection of several hundred fossil plants consists primarily of Jurassic to the late Pleistocene age. Their signature specimens in this category are 120 million-year-old fossil cycads from the Dakota Sandstone near Edgemont, South Dakota. It is one of the largest collections from the former Fossil Cycad National Monument. Other fossils include leaves, seeds, and petrified wood.

MINERAL COLLECTION

Their mineral collection consists of minerals of all types and meteorites. It encompasses over 75,000 specimens collected from all over the world for more than a century. Some are from countries that have since limited the export of certain minerals. Visitors find a fluorescent mineral room and a South Dakota room displaying minerals collected in South Dakota. Some come from mines that have closed such as the Homestake Mine in Lead, South Dakota.

Visitors will see sedimentary deposits, metamorphic deposits, vein and replacement deposits, geodes, and agates. The agate is the state gem. They also have ore from the Homestake Gold Mine and signage relating the mine’s history. Rocks are classified by their chemical composition: halides, sulfosalts, oxides, carbonates, and sulfides.

A new interactive exhibit, a hand-sized seismometer box called Raspberry Shake, measures movement in real-time. It provides visitors with an understanding of where earthquakes occur, what causes them, and about the movement under their feet. The display allows visitors to jump up and down on the floor and see the seismic waves they create in real-time on a monitor. They will learn how even the smallest movement is recorded in seismic waves. It also features a collection of geographic maps of different regions of the world. The map relates how old the events are with the larger the circle around one of these earthquakes, the larger the event.

ESPECIALLY FAMILY ORIENTED

A major goal is to provide science education. They have a Kid’s Area where children can play with casts and other educational toys. It features an eight-foot fossil track activity, upgraded exhibits, and kid’s furniture.

Each week, on Thursdays at 2:00 p.m., the museum has youngsters join them for a geology or paleontology themed story. Besides reading an age appropriate book, youngsters will participate in a related activity such as coloring, drawing, or making a puzzle.

Special family events are held throughout the year. Two very popular annual events are the Dinosaur Eggstravaganza held in April. Youngsters can uncover all there is to know about dinosaurs and how paleontologists dig up fossils. The Annual Night at the Museum is a Halloween event providing a safe place for children to trick-or-treat while participating in educational games and activities. To check out what is being offered during your stay in Rapid City, check out their web site.

Tours are provided for visitors of the museum during normal business hours. These are scheduled in advance by emailing [email protected].

DETAILS

The Museum Gift Shop and Bookstore contains such items as educational toys, rock and mineral samples, and geology reference books and guides.

The Museum of Geology is located in the center of the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology. The collections and research facility are located in the Paleontology Research Laboratory and are not open for public tours. Exhibits and public programs can be found at 501 E. Saint Joseph Street. The museum telephone number is (605) 394-2467. Winter hours are Monday through Saturday 8:30 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. and during the summer Monday through Saturday from 9:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. Admission is free with donations appreciated.

Black Hills Institute

Dinosaur Cast of Acrocanthosaurus

What a Mold Looks Like

Molds for Large Bones

How Steel is Put Inside the Skeleton

Making a Dinosaur Display - Stegosaurus

Peter Larson Holding the Jaws of an Oreodont

Skull of "Stan" T-Rex

Skull of "Jane" Nanotyrannus Lancensis

Replica of "Sue" T-Rex

Overall of the BHI Museum featuring "Billy" the Torosaurus

Fish Fossil at BHI

Large Ammonites at BHI

Nephrite Jade at BHI

Actinolite at BHI

Overall View of the Museum of Geology

Plesiosaur at Museum of Geology

Modern Alligator and Crocodile Limbs at Museum of Geology

Bulldog Fish at Museum of Geology

Fossil Crabs at the Museum of Geology

Tortoise at the Museum of Geology

Pregnant Oreodont with Twins at the Museum of Geology - Only Such Mounted Specimen

False Saber-Toothed Cat, Dinictis Felina, Member of Nimravidae Family

Goethite at the Museum of Geology

Enargite at the Museum of Geology

Geode at the Museum of Geology

Montomeryite at the Museum of Geology