Hello Everyone,

Most of the world’s mammoths died out between 10,000 and 12,000 years ago. The Mammoth Site in Hot Springs, South Dakota has the largest collection of Columbian mammoth bones left where they were found (en situ) of any location in the world. It also has the largest collection of mammoths in North America. At this working paleontology site, discovery, excavation, and preparation still take place. Scientists from around the world conduct research here and the public is invited to tour the facility.

HISTORY

If one could time travel back 140,000 years ago to the Hot Springs area, one would find a porous limestone layer under the surface. After many years, when the limestone eroded away, due to ground water moving through it, a large cavern formed. The weight of the sediment on top of this cavern caused its roof to collapse forming a 120 by 150-foot sinkhole. By creating cracks, the collapse also allowed lots of warm artesian water to bubble into this sinkhole, filling it like a swimming pool. The warm water resulted in lush vegetation growing around the edges of this steep-sided pond.

Mammoths are a matriarchal society with young males being expelled once they reach a certain age. These young males are known to be risk takers. It is believed that during the winter, when they faced starvation, they were attracted to this 90 to 95-degree sinkhole for bathing, drinking, and dining on vegetation that existed around the pond year round. Unfortunately, the sinkhole’s sides consisted of very slippery Spearfish shale. Once these young mammoths, mostly ages 12 to 29, waded into the sinkhole, they were trapped to die of drowning, exhaustion, or starvation. Now all that remains are their bones. As of 2019, 58 Columbian mammoths and 3 Woolly Mammoths have been discovered at Mammoth Site.

It is believed that mammoths originated in Africa and dispersed into Europe and Siberia. They entered North America via Siberia and the Bering Land Bridge about a million years ago. They gradually changed into the Ice Age mammals that are now being discovered, becoming extinct after thousands of years. The reason for their extinction is complex. Overkill by mankind, climatic change, and a comet hitting the Earth are the theories espoused.

More than 80 species of animals were attracted to the pit. Some were similar to those found today such as rabbits, moles, coyotes, wolves, and prairie dogs. Others became extinct including the American camel, giant short-faced bear, shrub ox, and two species of llama. Scientists have found fossils of birds, complete fish skeletons, and several species of clams, snail, and slugs. Most of these animals probably died around the sinkhole’s outer edge and had their remains washed into the pit.

Over a period of thousands of years, the sinkhole slowly filled with layers of silt, sand, and some gravel along with the bones of decaying animals. Dissolved minerals from the limestone began to cement it all together. The mud, which had originally trapped the mammoths, entombed and preserved their skeletons. The artesian spring diverted to Fall River and the pond filled with sediment. Water washed away the Spearfish shale and the soils from around the filled pond. This left a hill where the sinkhole once was.

Phil Anderson, who purchased the property in 1974, decided to level the hill and create a housing development. George Hanson, his heavy equipment operator, started to grade the land when his blade struck something that shone white in the sunlight. Upon close observation, he discovered a seven-foot long tusk, sliced in half lengthwise, along with some other bones.

Anderson contacted four colleges about the discovery, but they weren’t interested. His son, Dan, had taken courses in geology and archaeology. Dan contacted his professor, Dr. Larry Agenbroad of Chadron State College in Chadron, Nebraska. When Dr. Agenbroad arrived, he thought there were at least four to six mammoths. Since he was preoccupied with a site in southeastern Arizona, he sent Dr. Jim Mead (currently Mammoth Site’s Director of Research) and several members of his Arizona crew to salvage and stabilize the bones, tusks, teeth, and skull fragments that had been exposed.

In 1975, Dr. Agenbroad and Dr. Mead led a group of volunteer students to start excavating the site. Phil Anderson quickly realized the land’s value and sold it to the Mammoth Site of Hot Springs, SD, Inc. at cost. Mammoth Site became a National Natural Landmark in 1980.

BONEBED

What visitors see is a working paleontology dig site that is unparalleled anywhere in the world. The bones are not fossilized or petrified. They are in their original state and are so very fragile that they can be ground to dust with a finger. Many specimens are left exposed to allow visitors and scientists to see exactly where the bones were uncovered.

Check out the theater for a 10-minute video, Mammoth Trap: The Motion Picture about the site’s history and how the bones are preserved. After seeing the movie, enter the bonebed for a guided tour lasting 30 minutes. These feature a wireless Tour Guide system which enables visitors to have a clear digital sound of what the guide says. If you prefer, you can take the tour yourself by using the self-guided booklet or the smart phone app.

At the base of the stairs, you’ll spot Sinbad, a large fiberglass replica of a Columbian mammoth skeleton. It is a composite of casts molded from the Mammoth Site’s bones and the Huntington mammoth found in Central Utah. Sinbad represents a mammoth that weighed about 20,000 pounds and stood between 12 and 14 feet high. Today’s African and Asian elephants could walk underneath its chin without touching it.

When you enter the bonebed, you’ll see life-sized wooden cutouts of both species of mammoths. The Woolly mammoth was smaller and hairier. It weighed about 6 tons and was between 9 and 11 feet in height. It was found in such places as the northern United States and Canada while the Columbian settled in more temperate zones.

On your first stop, your guide will point out how high the sinkhole originally was and where the first bones were found. The entire sinkhole is inside the Mammoth Site. The visible red sediment marking the sinkhole’s perimeter is shale. It is red because of its iron content. Other colors of dirt are called fill sediment. They were washed into the sinkhole over a period of years.

At this stop, you’ll see the location of the artesian spring, the sinkhole’s source. Stop 16 marks the area of the main spring that flowed into the sinkhole.

At the second stop, view a butterfly shaped bone. It is a complete mammoth pelvis. This bone allows scientists to determine the mammoth’s sex. With females, the central area is wider because of the birthing canal. Female bones are also narrower. All mammoths at Mammoth Site have been determined to be males.

Visitors see Columbian mammoth teeth at stop three in the pit. These are important because they provide information on the mammoth’s age, species, and diet. Scientists have learned that mammoths were herbivores. They chewed on about 700 pounds of vegetation daily. Usually they had four functioning teeth in their mouth at one time - two upper and two lower.

An upside down Columbian mammoth skull is viewed at stop number four. On one of his top molars, you’ll see ridges. As their teeth wore down, others replaced them, kind of like being on a conveyor system. Mammoth teeth grew from the back of their jaws and pushed their teeth out the front. Then they either fell out, were spit out, or eaten by the animal.

They had six sets of cheek teeth (molars) throughout their life. They acquired their first three sets of molars by age six. The fourth arrived by age 13, the fifth by 27 years of age, and the last set at age 43. The last set of molars wore away at age 70 resulting in the mammal dying from a reduced ability to eat. The animal’s age could be determined by measuring the length, width, and depth of the tooth because each molar was somewhat larger than the one before it.

At stop five, you will see the skull of a woolly mammoth. Scientists can tell it’s a woolly because the teeth have more ridges on the first four inches of the teeth’s chewing surface. They are also more closely spaced than with the Columbian mammoth.

At this point on your tour, footsteps of Columbian mammoths can be seen on the wall. As the sinkhole aged, it became more mud and clay and less water. When mammoths walked on this mud and clay, their feet would sink in. As the mammoths tried to pull their feet out of the abyss, they created suction and the distortions that you see in these footprints.

A partial skeleton of a mammoth exists at stop six. It has many of the bones from the pelvis down. It’s believed that this animal died belly down at the edge of the sinkhole. It has not been determined what happened to the top half of the mammoth. Unless the remains are found placed together, Mammoth Site staff cannot determine which bones belong to which mammoth since the DNA has been lost.

At number seven in the pit, you’ll find a variety of tools. Commonplace items like paint brushes, chisels, dental picks, trowels, and toothbrushes are used in order to prevent damage to bones. No power tools are used. All specimens are documented using state-of-the-art mapping techniques.

The sediments that the scientists excavate are also important. Part of this consists of the bones of smaller mammals such as rodents, rabbits, fish, and amphibians. Others are shells of snails, clams, insects, and crustaceans. These give clues to the area’s ecology.

The primary excavation at Mammoth Site takes place in the summer when staff holds a Junior Paleontologist Excavation Program, Atlatl throwing class, and Advanced Paleontologist Excavation Program. These run between June 1 and August 15. See their site for details.

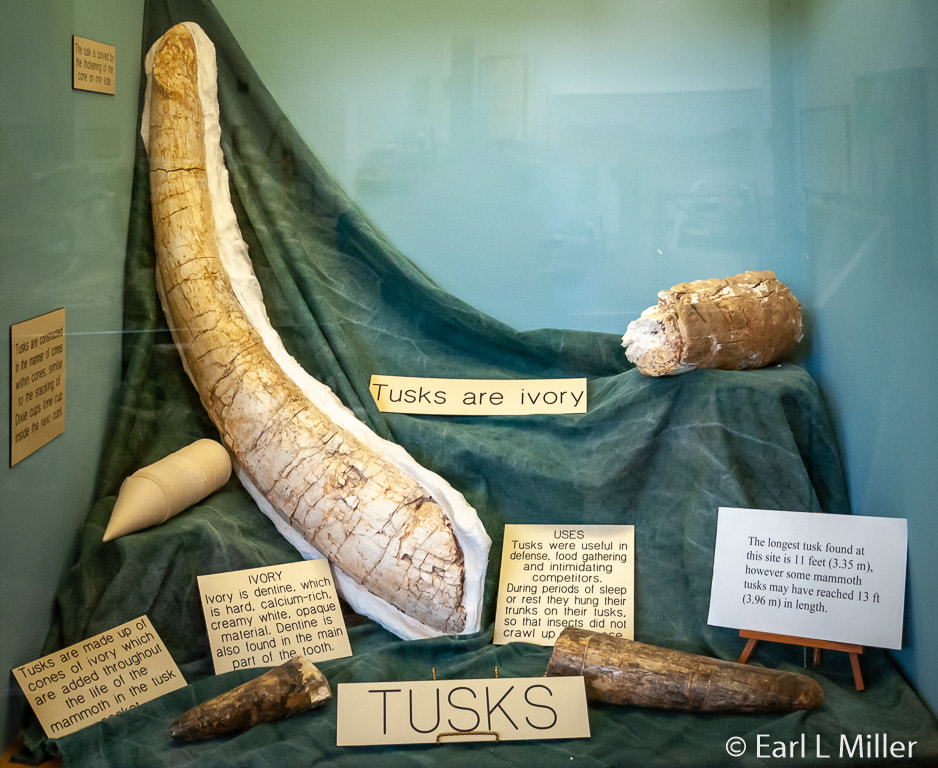

You will find tusks at stop eight. One is straight which is unique. Scientists have discovered 122 tusks which is how they know at least 61 mammoths perished in the sinkhole. They believe the number will increase with further excavation.

Mammoths had milk tusks the first year. Their main tusks grew throughout their lifetime with new layers being added. If the tusks fell out, the animal just started growing them again. The thickness showed scientists if the animal was sick and how well he was eating.

Tusks are a type of teeth that protrude from the upper jaw. They are made up of cones of ivory which are added throughout the mammoth’s life in the tusk socket. Cones were placed within cones similar to the stacking of Dixie cups, one right inside another. Tusks were used for fighting/defense, foraging for food, and mating displays. The longest tusk found at Mammoth Site was 11 feet.

The trunk was used for breathing, smelling, drinking, and food gathering. With over 40,000 muscles and tendons, it also functioned as an extra limb. It could flex, stretch, bend, and twist. The “fingers” at its end could pluck blades of grass. When mammoths slept, they hung their trunks on their tusks so insects didn’t crawl up their noses.

At this point, your guide may point out to you silhouettes modeled after actual animals found at the sinkhole. These are of a giant short-faced bear, Camel, shrub ox, and a large headed llama. You will also see cutouts for size comparison of a Columbia mammoth, woolly mammoth, pygmy mammoth, Asian elephant, and African elephant.

At stop nine, your guide will point out the jaw of a Columbian mammoth. The animal ate by grinding the jaw on the bottom.

A flattened tusk is located at stop 10. In 1983, when the tusk was first excavated, it was found that it had been scraped by the bulldozer in 1974.

At site number 11, you will find the second most complete mammoth. It’s missing the skull. It was first named Marie Antoinette. However, once its pelvis was discovered, it was renamed Murray.

At number 12, you will find the site’s only cast. It is the skull of a giant short-faced bear skeleton. The original was removed from the sinkhole for further studies. If this bear stood on its hind legs, it could reach a two-story window. They traveled at 40 miles per hour. It is believed that the Columbian mammoth was prey for this bear when entrapped in the sinkhole pond.

Skeletal remains of two individuals have been found. One bear they discovered was a young adult. Besides the skull, they found a lower jaw, part of an upper arm bone, one thigh bone, and part of the hip bone. In another place in the bonebed, a complete skeleton of a giant short-faced bear is displayed.

The most complete mammoth skeleton is at stop 13. It is also the oldest at approximately 47 years of age based on the measurements of his teeth. This skeleton is nicknamed Napoleon. He would have stood about 14 feet at the shoulder and weighed between eight and ten tons. Behind him is the youngest specimen. He was 12 years old when he died.

One of the best preserved specimens - a skull called Beauty is at stop 14. The tip of its right tusk has been chipped off. That happened either during excavation or before the animal died. Above it, at spot 15, are the only two skulls discovered with intact tusks.

Core samples were drilled at stop 17 to determine the sinkhole’s depth. Due to time constraints, the South Dakota Geological Survey was unable to dig any further than 67 feet, but they were still turning up bone and ivory fragments at that level. How many mammoths are left to be discovered is unknown at this time. It is estimated that 1,200 bones and fragments are in the pit including those not completely excavated. The current excavation has reached 22 feet. It is estimated that it will take three or more generations to reach the sinkhole’s bottom as its depth is not totally known.

PREPARATION LAB

After your guided tour, feel free to walk around and view the site again. Photographs are encouraged. You may then want to view their preparation lab downstairs via viewing windows. We were told by our guide that one hour in the field equates to ten hours in the lab doing curative work.

During excavation, the sinkhole’s sediment is bagged and tagged with the locality and mapping coordinates. These bags, weighing up to 40 pounds, are taken outside where they are washed over a series of smaller and smaller screens. The process separates the smaller rocks and fossils from the sinkhole sediments.

When the majority of sediment rinses away, grains of gravel are left. While the concentrate is still wet, it is checked for tiny fossils, then dried, bagged again, and stored in the Mammoth Site laboratory. Lab technicians later handpick through the concentrate to find micro fauna, tiny fossil teeth, bones, and shells. These specimens are carefully analyzed and their data precisely recorded. Micro faunas are important findings since they provide clues as to their former environments.

Unlike dinosaur bones, mammoth bones at the Mammoth Site are not petrified or turned to stone. They have had their original organic material leached out by water so are very dry. All have been treated with preservatives to protect them from damage and deterioration. Mammoth Site has used different preservatives over the years. The first, one called Glytol, turned the bones brownish and made them look dirty. The current one, Peraloid D72, seeps in without discoloration. It provides a natural color as if a preservative wasn’t on it.

Most bones have been left in place. Sometimes they are removed for more complete scientific study, preservation concerns, or to gain access to deeper areas of the excavation.

Before removal, they are positioned on a small dirt pedestal. A plaster field jacket, similar to a cast for a broken arm, is placed around the bone for protection. After the plaster hardens, the bone is cut away from the pedestal and taken to the laboratory downstairs.

In the lab, the bones are identified then gently cleaned, repaired, and treated with preservative. Most of the work is done by hand. Using air tools that are like miniature jackhammers, hard sediment crust is chipped away from the bone. The work can be like doing a jigsaw puzzle since shape, color, and textures provide clues as to where the pieces of bone fit.

Peraloid is mixed with ethanol and applied to the bone’s interior. This consolidates and hardens the bone from the inside out. Some require gallons of this liquid and may take months to be fully preserved. Once the bone is stabilized, it is numbered, catalogued, and stored.

Its new home is the bone storage vault where it is studied by Mammoth site paleontologists as well as from other institutions and universities. All specimens are stored here on the site. Sometimes the molding and casting department creates replicas of these bones to send to scientists and educators from across the globe.

OTHER RESEARCH

The Exhibit Hall will give you insight into the research Mammoth Site is conducting worldwide. The focus is on the Ice Age. Their paleontologists work in conjunction with Wind Cave National Park at Persistence Cave. They are prospecting for Ice Age faunas from other Black Hills areas where they are finding bison remains among many other species.

They are also conducting research worldwide in such places as caves in the western Grand Canyon, sinkholes on various Bahama islands, shelters and alluvial deposits on the Northern Channel Islands, and caves in the Great Basin of Nevada. Other explorations include alluvial deposits in Sonora (Mexico) and Texas and caves in Western Australia and southernmost China. While most of the hands-on research is on proboscideans (i.e. elephants and mammoths), another major interest is understanding the history of bison.

The Mammoth Site Microfaunal Lab has a modern comparative skeleton collection of mammals, lizards, snakes, frogs, and salamanders. They also have a dung collection. Dung is studied because it helps understand the past fauna along with the animals’ diet and environment. By using sophisticated lab techniques, dung can indicate who made it, when, what the animal ate, and what the local environment was like at the time. Scientists have found 98% of the dung consists of grasses, seeds, and rushes. No mammoth dung has been found at Mammoth Site because it decayed in the sinkhole’s warm water.

EXHIBIT HALL ABOUT THE ICE AGE

In the Hall, visitors find replicas of baby woolly mammoths, Dima and Lyuba and a skeletal replica of Napoleon, a Columbian mammoth.

You’ll easily spot the mammoth hut composed of 121 mammoth bone replicas. The real huts can be seen on the plains of the Ukraine, Poland, and the Czech Republic. No evidence of these has appeared in North America.

Some huts were built 27,000 years ago. Those in the Ukraine date between 12,000 and 19,000 years. Some villages had up to six bone huts occupied by as many as 40 people. The houses may have served as a semi permanent base camp. Many contained storage pits, hearths, and stone tool debris.

One side of the room is devoted to bison. It includes a map where they were found and some skulls. The Clovis culture existed in North America at the end of the last Ice Age. They used a spear point to hunt and butcher mammoths, mastodons, bison, horses, and camels. Wallboards depict their various hunting methods including corralling them and also driving them over a buffalo jump.

The Lang-Ferguson site in southwestern South Dakota is the state’s only known Clovis mammoth butchery site. It is 13,100 years old. The site contains the remains of an adult and a juvenile mammoth butchered by the Clovis along a small pond. A knife flaked from the juvenile mammoth’s bones and three Clovis spear points were discovered nearby.

DETAILS

The Mammoth Site of Hot Springs is located at 1800 US 18 Bypass in Hot Springs. Its telephone number is (605) 745-6017. It is open year round with 30 minute guided tours. Plan on at least 90 minutes here. Since hours vary throughout the year with the last tour occurring one hour before closing, check the site before you go. Admission is $11.05 for adults, $9.04 for seniors, and $8.03 for children and active or retired military.

Most of the world’s mammoths died out between 10,000 and 12,000 years ago. The Mammoth Site in Hot Springs, South Dakota has the largest collection of Columbian mammoth bones left where they were found (en situ) of any location in the world. It also has the largest collection of mammoths in North America. At this working paleontology site, discovery, excavation, and preparation still take place. Scientists from around the world conduct research here and the public is invited to tour the facility.

HISTORY

If one could time travel back 140,000 years ago to the Hot Springs area, one would find a porous limestone layer under the surface. After many years, when the limestone eroded away, due to ground water moving through it, a large cavern formed. The weight of the sediment on top of this cavern caused its roof to collapse forming a 120 by 150-foot sinkhole. By creating cracks, the collapse also allowed lots of warm artesian water to bubble into this sinkhole, filling it like a swimming pool. The warm water resulted in lush vegetation growing around the edges of this steep-sided pond.

Mammoths are a matriarchal society with young males being expelled once they reach a certain age. These young males are known to be risk takers. It is believed that during the winter, when they faced starvation, they were attracted to this 90 to 95-degree sinkhole for bathing, drinking, and dining on vegetation that existed around the pond year round. Unfortunately, the sinkhole’s sides consisted of very slippery Spearfish shale. Once these young mammoths, mostly ages 12 to 29, waded into the sinkhole, they were trapped to die of drowning, exhaustion, or starvation. Now all that remains are their bones. As of 2019, 58 Columbian mammoths and 3 Woolly Mammoths have been discovered at Mammoth Site.

It is believed that mammoths originated in Africa and dispersed into Europe and Siberia. They entered North America via Siberia and the Bering Land Bridge about a million years ago. They gradually changed into the Ice Age mammals that are now being discovered, becoming extinct after thousands of years. The reason for their extinction is complex. Overkill by mankind, climatic change, and a comet hitting the Earth are the theories espoused.

More than 80 species of animals were attracted to the pit. Some were similar to those found today such as rabbits, moles, coyotes, wolves, and prairie dogs. Others became extinct including the American camel, giant short-faced bear, shrub ox, and two species of llama. Scientists have found fossils of birds, complete fish skeletons, and several species of clams, snail, and slugs. Most of these animals probably died around the sinkhole’s outer edge and had their remains washed into the pit.

Over a period of thousands of years, the sinkhole slowly filled with layers of silt, sand, and some gravel along with the bones of decaying animals. Dissolved minerals from the limestone began to cement it all together. The mud, which had originally trapped the mammoths, entombed and preserved their skeletons. The artesian spring diverted to Fall River and the pond filled with sediment. Water washed away the Spearfish shale and the soils from around the filled pond. This left a hill where the sinkhole once was.

Phil Anderson, who purchased the property in 1974, decided to level the hill and create a housing development. George Hanson, his heavy equipment operator, started to grade the land when his blade struck something that shone white in the sunlight. Upon close observation, he discovered a seven-foot long tusk, sliced in half lengthwise, along with some other bones.

Anderson contacted four colleges about the discovery, but they weren’t interested. His son, Dan, had taken courses in geology and archaeology. Dan contacted his professor, Dr. Larry Agenbroad of Chadron State College in Chadron, Nebraska. When Dr. Agenbroad arrived, he thought there were at least four to six mammoths. Since he was preoccupied with a site in southeastern Arizona, he sent Dr. Jim Mead (currently Mammoth Site’s Director of Research) and several members of his Arizona crew to salvage and stabilize the bones, tusks, teeth, and skull fragments that had been exposed.

In 1975, Dr. Agenbroad and Dr. Mead led a group of volunteer students to start excavating the site. Phil Anderson quickly realized the land’s value and sold it to the Mammoth Site of Hot Springs, SD, Inc. at cost. Mammoth Site became a National Natural Landmark in 1980.

BONEBED

What visitors see is a working paleontology dig site that is unparalleled anywhere in the world. The bones are not fossilized or petrified. They are in their original state and are so very fragile that they can be ground to dust with a finger. Many specimens are left exposed to allow visitors and scientists to see exactly where the bones were uncovered.

Check out the theater for a 10-minute video, Mammoth Trap: The Motion Picture about the site’s history and how the bones are preserved. After seeing the movie, enter the bonebed for a guided tour lasting 30 minutes. These feature a wireless Tour Guide system which enables visitors to have a clear digital sound of what the guide says. If you prefer, you can take the tour yourself by using the self-guided booklet or the smart phone app.

At the base of the stairs, you’ll spot Sinbad, a large fiberglass replica of a Columbian mammoth skeleton. It is a composite of casts molded from the Mammoth Site’s bones and the Huntington mammoth found in Central Utah. Sinbad represents a mammoth that weighed about 20,000 pounds and stood between 12 and 14 feet high. Today’s African and Asian elephants could walk underneath its chin without touching it.

When you enter the bonebed, you’ll see life-sized wooden cutouts of both species of mammoths. The Woolly mammoth was smaller and hairier. It weighed about 6 tons and was between 9 and 11 feet in height. It was found in such places as the northern United States and Canada while the Columbian settled in more temperate zones.

On your first stop, your guide will point out how high the sinkhole originally was and where the first bones were found. The entire sinkhole is inside the Mammoth Site. The visible red sediment marking the sinkhole’s perimeter is shale. It is red because of its iron content. Other colors of dirt are called fill sediment. They were washed into the sinkhole over a period of years.

At this stop, you’ll see the location of the artesian spring, the sinkhole’s source. Stop 16 marks the area of the main spring that flowed into the sinkhole.

At the second stop, view a butterfly shaped bone. It is a complete mammoth pelvis. This bone allows scientists to determine the mammoth’s sex. With females, the central area is wider because of the birthing canal. Female bones are also narrower. All mammoths at Mammoth Site have been determined to be males.

Visitors see Columbian mammoth teeth at stop three in the pit. These are important because they provide information on the mammoth’s age, species, and diet. Scientists have learned that mammoths were herbivores. They chewed on about 700 pounds of vegetation daily. Usually they had four functioning teeth in their mouth at one time - two upper and two lower.

An upside down Columbian mammoth skull is viewed at stop number four. On one of his top molars, you’ll see ridges. As their teeth wore down, others replaced them, kind of like being on a conveyor system. Mammoth teeth grew from the back of their jaws and pushed their teeth out the front. Then they either fell out, were spit out, or eaten by the animal.

They had six sets of cheek teeth (molars) throughout their life. They acquired their first three sets of molars by age six. The fourth arrived by age 13, the fifth by 27 years of age, and the last set at age 43. The last set of molars wore away at age 70 resulting in the mammal dying from a reduced ability to eat. The animal’s age could be determined by measuring the length, width, and depth of the tooth because each molar was somewhat larger than the one before it.

At stop five, you will see the skull of a woolly mammoth. Scientists can tell it’s a woolly because the teeth have more ridges on the first four inches of the teeth’s chewing surface. They are also more closely spaced than with the Columbian mammoth.

At this point on your tour, footsteps of Columbian mammoths can be seen on the wall. As the sinkhole aged, it became more mud and clay and less water. When mammoths walked on this mud and clay, their feet would sink in. As the mammoths tried to pull their feet out of the abyss, they created suction and the distortions that you see in these footprints.

A partial skeleton of a mammoth exists at stop six. It has many of the bones from the pelvis down. It’s believed that this animal died belly down at the edge of the sinkhole. It has not been determined what happened to the top half of the mammoth. Unless the remains are found placed together, Mammoth Site staff cannot determine which bones belong to which mammoth since the DNA has been lost.

At number seven in the pit, you’ll find a variety of tools. Commonplace items like paint brushes, chisels, dental picks, trowels, and toothbrushes are used in order to prevent damage to bones. No power tools are used. All specimens are documented using state-of-the-art mapping techniques.

The sediments that the scientists excavate are also important. Part of this consists of the bones of smaller mammals such as rodents, rabbits, fish, and amphibians. Others are shells of snails, clams, insects, and crustaceans. These give clues to the area’s ecology.

The primary excavation at Mammoth Site takes place in the summer when staff holds a Junior Paleontologist Excavation Program, Atlatl throwing class, and Advanced Paleontologist Excavation Program. These run between June 1 and August 15. See their site for details.

You will find tusks at stop eight. One is straight which is unique. Scientists have discovered 122 tusks which is how they know at least 61 mammoths perished in the sinkhole. They believe the number will increase with further excavation.

Mammoths had milk tusks the first year. Their main tusks grew throughout their lifetime with new layers being added. If the tusks fell out, the animal just started growing them again. The thickness showed scientists if the animal was sick and how well he was eating.

Tusks are a type of teeth that protrude from the upper jaw. They are made up of cones of ivory which are added throughout the mammoth’s life in the tusk socket. Cones were placed within cones similar to the stacking of Dixie cups, one right inside another. Tusks were used for fighting/defense, foraging for food, and mating displays. The longest tusk found at Mammoth Site was 11 feet.

The trunk was used for breathing, smelling, drinking, and food gathering. With over 40,000 muscles and tendons, it also functioned as an extra limb. It could flex, stretch, bend, and twist. The “fingers” at its end could pluck blades of grass. When mammoths slept, they hung their trunks on their tusks so insects didn’t crawl up their noses.

At this point, your guide may point out to you silhouettes modeled after actual animals found at the sinkhole. These are of a giant short-faced bear, Camel, shrub ox, and a large headed llama. You will also see cutouts for size comparison of a Columbia mammoth, woolly mammoth, pygmy mammoth, Asian elephant, and African elephant.

At stop nine, your guide will point out the jaw of a Columbian mammoth. The animal ate by grinding the jaw on the bottom.

A flattened tusk is located at stop 10. In 1983, when the tusk was first excavated, it was found that it had been scraped by the bulldozer in 1974.

At site number 11, you will find the second most complete mammoth. It’s missing the skull. It was first named Marie Antoinette. However, once its pelvis was discovered, it was renamed Murray.

At number 12, you will find the site’s only cast. It is the skull of a giant short-faced bear skeleton. The original was removed from the sinkhole for further studies. If this bear stood on its hind legs, it could reach a two-story window. They traveled at 40 miles per hour. It is believed that the Columbian mammoth was prey for this bear when entrapped in the sinkhole pond.

Skeletal remains of two individuals have been found. One bear they discovered was a young adult. Besides the skull, they found a lower jaw, part of an upper arm bone, one thigh bone, and part of the hip bone. In another place in the bonebed, a complete skeleton of a giant short-faced bear is displayed.

The most complete mammoth skeleton is at stop 13. It is also the oldest at approximately 47 years of age based on the measurements of his teeth. This skeleton is nicknamed Napoleon. He would have stood about 14 feet at the shoulder and weighed between eight and ten tons. Behind him is the youngest specimen. He was 12 years old when he died.

One of the best preserved specimens - a skull called Beauty is at stop 14. The tip of its right tusk has been chipped off. That happened either during excavation or before the animal died. Above it, at spot 15, are the only two skulls discovered with intact tusks.

Core samples were drilled at stop 17 to determine the sinkhole’s depth. Due to time constraints, the South Dakota Geological Survey was unable to dig any further than 67 feet, but they were still turning up bone and ivory fragments at that level. How many mammoths are left to be discovered is unknown at this time. It is estimated that 1,200 bones and fragments are in the pit including those not completely excavated. The current excavation has reached 22 feet. It is estimated that it will take three or more generations to reach the sinkhole’s bottom as its depth is not totally known.

PREPARATION LAB

After your guided tour, feel free to walk around and view the site again. Photographs are encouraged. You may then want to view their preparation lab downstairs via viewing windows. We were told by our guide that one hour in the field equates to ten hours in the lab doing curative work.

During excavation, the sinkhole’s sediment is bagged and tagged with the locality and mapping coordinates. These bags, weighing up to 40 pounds, are taken outside where they are washed over a series of smaller and smaller screens. The process separates the smaller rocks and fossils from the sinkhole sediments.

When the majority of sediment rinses away, grains of gravel are left. While the concentrate is still wet, it is checked for tiny fossils, then dried, bagged again, and stored in the Mammoth Site laboratory. Lab technicians later handpick through the concentrate to find micro fauna, tiny fossil teeth, bones, and shells. These specimens are carefully analyzed and their data precisely recorded. Micro faunas are important findings since they provide clues as to their former environments.

Unlike dinosaur bones, mammoth bones at the Mammoth Site are not petrified or turned to stone. They have had their original organic material leached out by water so are very dry. All have been treated with preservatives to protect them from damage and deterioration. Mammoth Site has used different preservatives over the years. The first, one called Glytol, turned the bones brownish and made them look dirty. The current one, Peraloid D72, seeps in without discoloration. It provides a natural color as if a preservative wasn’t on it.

Most bones have been left in place. Sometimes they are removed for more complete scientific study, preservation concerns, or to gain access to deeper areas of the excavation.

Before removal, they are positioned on a small dirt pedestal. A plaster field jacket, similar to a cast for a broken arm, is placed around the bone for protection. After the plaster hardens, the bone is cut away from the pedestal and taken to the laboratory downstairs.

In the lab, the bones are identified then gently cleaned, repaired, and treated with preservative. Most of the work is done by hand. Using air tools that are like miniature jackhammers, hard sediment crust is chipped away from the bone. The work can be like doing a jigsaw puzzle since shape, color, and textures provide clues as to where the pieces of bone fit.

Peraloid is mixed with ethanol and applied to the bone’s interior. This consolidates and hardens the bone from the inside out. Some require gallons of this liquid and may take months to be fully preserved. Once the bone is stabilized, it is numbered, catalogued, and stored.

Its new home is the bone storage vault where it is studied by Mammoth site paleontologists as well as from other institutions and universities. All specimens are stored here on the site. Sometimes the molding and casting department creates replicas of these bones to send to scientists and educators from across the globe.

OTHER RESEARCH

The Exhibit Hall will give you insight into the research Mammoth Site is conducting worldwide. The focus is on the Ice Age. Their paleontologists work in conjunction with Wind Cave National Park at Persistence Cave. They are prospecting for Ice Age faunas from other Black Hills areas where they are finding bison remains among many other species.

They are also conducting research worldwide in such places as caves in the western Grand Canyon, sinkholes on various Bahama islands, shelters and alluvial deposits on the Northern Channel Islands, and caves in the Great Basin of Nevada. Other explorations include alluvial deposits in Sonora (Mexico) and Texas and caves in Western Australia and southernmost China. While most of the hands-on research is on proboscideans (i.e. elephants and mammoths), another major interest is understanding the history of bison.

The Mammoth Site Microfaunal Lab has a modern comparative skeleton collection of mammals, lizards, snakes, frogs, and salamanders. They also have a dung collection. Dung is studied because it helps understand the past fauna along with the animals’ diet and environment. By using sophisticated lab techniques, dung can indicate who made it, when, what the animal ate, and what the local environment was like at the time. Scientists have found 98% of the dung consists of grasses, seeds, and rushes. No mammoth dung has been found at Mammoth Site because it decayed in the sinkhole’s warm water.

EXHIBIT HALL ABOUT THE ICE AGE

In the Hall, visitors find replicas of baby woolly mammoths, Dima and Lyuba and a skeletal replica of Napoleon, a Columbian mammoth.

You’ll easily spot the mammoth hut composed of 121 mammoth bone replicas. The real huts can be seen on the plains of the Ukraine, Poland, and the Czech Republic. No evidence of these has appeared in North America.

Some huts were built 27,000 years ago. Those in the Ukraine date between 12,000 and 19,000 years. Some villages had up to six bone huts occupied by as many as 40 people. The houses may have served as a semi permanent base camp. Many contained storage pits, hearths, and stone tool debris.

One side of the room is devoted to bison. It includes a map where they were found and some skulls. The Clovis culture existed in North America at the end of the last Ice Age. They used a spear point to hunt and butcher mammoths, mastodons, bison, horses, and camels. Wallboards depict their various hunting methods including corralling them and also driving them over a buffalo jump.

The Lang-Ferguson site in southwestern South Dakota is the state’s only known Clovis mammoth butchery site. It is 13,100 years old. The site contains the remains of an adult and a juvenile mammoth butchered by the Clovis along a small pond. A knife flaked from the juvenile mammoth’s bones and three Clovis spear points were discovered nearby.

DETAILS

The Mammoth Site of Hot Springs is located at 1800 US 18 Bypass in Hot Springs. Its telephone number is (605) 745-6017. It is open year round with 30 minute guided tours. Plan on at least 90 minutes here. Since hours vary throughout the year with the last tour occurring one hour before closing, check the site before you go. Admission is $11.05 for adults, $9.04 for seniors, and $8.03 for children and active or retired military.

Exterior of Mammoth Site

Area Near the Gift Shop

Entrance to Bonebed

Sinbad

Columbian Mammoth Molars at Stop 3

Paleontologist Tools at Stop Seven

Close Up of Mammoth Bone Found at Stop Seven

Some of the Tusks at Stop Eight

Close Up of the Tusks at Stop Eight

Giant Short-Faced Bear Replica

Flattened Tusk at Stop 10

Murray at Stop 11

Murray's Neck Bones at Stop 11

Paleontologist at Work

The Most Complete Mammoth Skeleton Found - Stop 13

Beauty - A Skull That is One of the Best Preserved Specimens - Stop 14

One of Two Skulls Found With Tusks Intact - Stop 15

Spring Conduit Area - Stop 16

Preparation Lab

Mammoth Molars in Exhibit Hall

Mammoth Tusks in Exhibit Hall

Dima, A Baby Woolly Mammoth Replica, in the Exhibit Hall

Napoleon and Overview of the Exhibit Hall

Mammoth Hut in the Exhibit Hall

Bison Skull from Their Bison Display in the Exhibit Hall