Hello Everyone,

The Lewis and Clark Historic Trail, which is approximately 4,900 miles long, extends over 16 states from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania to the mouth of the Columbia River near present day Astoria, Oregon. Congress established the trail in 1978 as one of four original national historic trails. Along it, many sites, including several visitor centers, beckon to visitors. We explored three of them in Nebraska and Iowa.

NATIONAL HEADQUARTERS OF THE LEWIS AND CLARK TRAIL

The national headquarters for the trail is in Omaha, Nebraska at the National Park Service’s Midwest Regional Office. The building, which houses a public visitor center, was dedicated in 2004 during the expedition’s 200th anniversary celebration.

The Center is the place to obtain brochures on sites along the trail, the national parks, and Omaha. You can shop its bookstore, watch the 28-minute film Lewis and Clark - Corps of Discovery, ask rangers questions, and request assistance with trip planning.

Signboards and a few cases of artifacts add to your visit. This includes a variety of pelts and parts of a bison. Native Americans used all of the bison from the bladder to the hide. You’ll also spot a grizzly pelt and skull. Grizzlies were encountered numerous times by the Corps.

One signboard mentions the five kinds of weaponry the Corps used for defense and their daily hunt for food. It explains muskets, an air rifle, a swivel gun, a blunderbuss, and lead canisters.

The air rifle, Lewis’s own weapon, was demonstrated at Native American council meetings. A swivel gun was a small bronze cannon located on the keelboat’s bow while blunderbusses (heavy shotguns) were on the stern. Blunderbusses were fired for three reasons: signaling, saluting, and celebrations. Lead canisters served two purposes. They each held four pounds of gun powder. Composed of sheet lead, the cans could be melted down and used for bullets.

Another sign describes transportation. The Corps employed bull boats, an iron boat, pirogues, a keelboat, dugout canoes, and horses. Bull boats were made of bison hides stretched over a wooden frame. Pine pitch was used to make the vessels watertight. Horses acquired from the Shoshones enabled the Corps to cross the Rocky Mountains. The Nez Perce taught the Corps to use fire to build canoes from cottonwood and pine trees. These dugouts were up to 33 feet long.

The 200-pound collapsible iron boat was Lewis’s invention. The Corps failed to seal the hides by covering it with tar, causing the boat to sink. This led Clark to design a cart that moved supplies and the other boats overland.

Before leaving on the expedition, Meriwether Lewis shopped in Philadelphia for many of the supplies he would need on the trip including those for mapping. The cartography case includes reproductions of a magnet, needles, and two compasses Lewis would have purchased in 1803.

Many items used on the expedition were lost or destroyed on the journey. However, a silver-plated pocket compass Lewis had bought became his keepsake and ended up in the Smithsonian.

In the same case, you can also see a replica of a map Clark made. He was the first to map the Missouri River in its entirety as well as the Northwest. His maps were used, because of their accuracy, by many who came after him. In 4,000 miles, Clark was only off by 40 miles in his calculations.

The case of trade goods consists of reproductions of a Sioux tobacco pouch, chief’s hat from Fort Clatsop, and wampum purchased by Lewis in 1803. The Corps of Discovery purchased a canoe with a 36-foot strand of wampum beads.

Lewis asked two Clatsop women to make hats for them. Since they were tightly woven of cedar and bear grass and because of their shape, the hats were rain repellent. With the Mandans, the Corps traded medical services and metal artifacts for the corn and other produce the tribe still grows today.

One of the goals of the expedition was to collect animal and plant specimens to send back to Jefferson. A case at the Center houses taxidermied specimens similar to those collected on the trip. You can see a a Yellow-bellied marmot from Idaho and a long-tailed weasel from North Dakota.

Last year, ranger programs occurred in the morning and afternoon during summer months on most days. However, due to decreased staff, the programs were discontinued this year. The Center hopes to resume them in 2020.

DETAILS

During the summer, this visitor center is open daily while during the winter, it is closed on weekends. Summer hours are Monday through Friday from 8:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. and on weekends from 9:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Winter hours are Monday through Friday from 8:00 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Admission is free. The address is 601 Riverfront Drive in Omaha. The phone number is (402) 661-1804. For more information, go to their web site.

MISSOURI RIVER BASIN - LEWIS AND CLARK INTERPRETATIVE TRAIL & VISITOR CENTER

What makes this Center near Nebraska City, Nebraska different from all other museums and centers along the Trail is its unique focus on the Corps of Discovery’s flora, fauna, and scientific discoveries recorded in the journals of Lewis and Clark. You’ll learn about the animals, birds, fish, plants and medicine of the expedition. On three floors, numerous interactive exhibits, superb mounted species in quality dioramas, and bird calls make this an enjoyable experience. During the second Saturday of each month during the summer, the Center has reenactors.

Before entering, step on board a full sized replica of the keelboat Lewis and Clark used. The 55-foot keelboat was 8 feet 4 inches in width. It drew two to 2.5 feet of water when loaded with an estimated 12 to 15 tons of supplies. An enclosure at the stern was Clark’s office. He was responsible for maps and journals.

Built in Pittsburgh, to Lewis’s specifications, it traveled down the Ohio River, picking up Clark in Kentucky. It continued down the Ohio River then up the Mississippi River to the mouth of the Missouri River near St. Louis. On May 21, 1804, the keelboat and two pirogues set out from St. Charles with a crew of 44.The Corps used the keelboat on the expedition until they reached the Mandan village in North Dakota during November of 1804. After Lewis and Clark loaded it with specimens of plants and animals to be sent to President Jefferson, the boat and its crew of 12 men left Fort Mandan on April 2, 1805. That was the same day the permanent party headed west in the pirogues. The keelboat reached St. Louis on May 20, 1805.

The Center’s replica was used as a movie prop for the IMAX movie Lewis and Clark: The Great Journey West. It is unsure that the replica follows the original plan because historians don’t know whether the historical boat’s keel was round or flat. Most think it was round.

Inside the Center, note the sculpture of Thomas Jefferson titled The Naturalist. It greets people at the entrance and was sculpted by Carol A. Grende.

There is also a sculpture of Seaman, who was Lewis’s Newfoundland dog. He saved Lewis’s life twice. He got between him and an 8-1/2 foot grizzly and diverted a bison bull from camp. He also was excellent at hunting squirrels, beavers, and even antelope.

You’ll see a mural of the Nebraska City area in 1804 when trees only grew along the river. Nebraska City became a supply center, a stopping point on the river, that at one time was larger than Omaha. When the transcontinental railroad was built through Omaha/Council Bluffs, Nebraska City lost traffic and the population fell from 12,000 to 5,000.

Inside the Center, visitors find a reproduction of a 32-foot, white pirogue (long, narrow riverboat). It’s the smaller of two pirogues, the other of which was red, used on the expedition to Great Falls, Montana where the Corps made canoes. The only true sketch of the white pirogue was done by Clark in Illinois during the winter of 1803-1804 when he estimated how much equipment the boats could carry.

The white pirogue was to return the first summer with dispatches for President Jefferson. Instead, it traveled further than the other boats and returned to St. Louis in September 1806 as the command vessel. The one at the museum was built in 1999 for the same movie as the keelboat.

Like the original boat, this one was constructed of poplar planks. The original had a stern tiller, a mast, and sails. The men sometimes stretched an awning over the stern to provide shade. Six oarsmen rowed it standing up. A bowman was posted in front to watch for snags and sandbars. A helmsman, in the rear, steered using a tiller as a rudder.

They didn’t always row the boat to propel it. If the wind was right, they used the sails. They also sometimes used poles to push against the river bottom or tied ropes to the boats and towed them along. Youngsters are allowed to board this vessel and pretend to steer it. Look for the badger and cinnamon bear pelts on board.

One interactive is fascinating and I could have spent hours on it. The Center has listed on cards all of the 300 new plants (178) and animals (122) that Lewis and Clark discovered during their expedition. Each card has a picture and notes where each species was encountered, the date, and its natural habitat.

An interactive touchscreen exhibit allows visitors to experience sights and sounds while viewing the migratory territories of each bird species recorded by Lewis and Clark. While hiking the Center’s trails, you’re likely to view many bird varieties along the flyway between Canada and South America.

A third interactive is about dead reckoning. You can estimate how far you are from points by using your vision.

As we learned in Omaha, very few artifacts remain from the expedition. Most are replicas. For example, the captain’s tent you’ll see reveals the size they would have used.

At another interactive, you can scan in cards to learn what plants the Corps discovered on the trail and how they used them. For example, the exceptionally strong wood of the osage orange tree was used for bows and arrows. You’ll find this plant along the trails surrounding the Center.

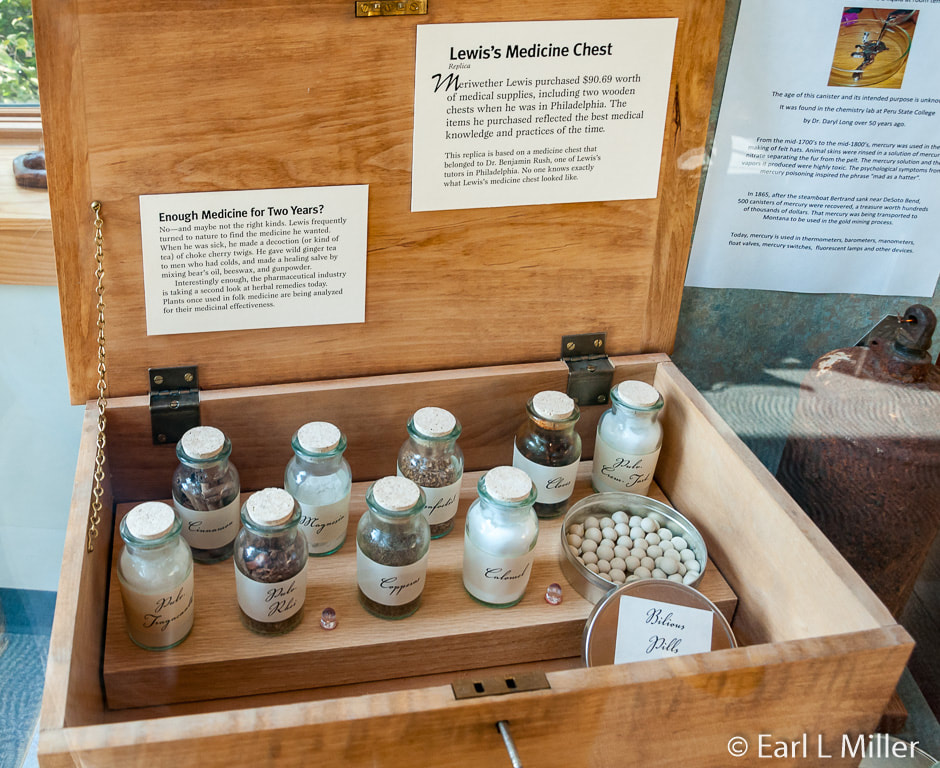

One exhibit deals with medicine. Jefferson did not send a doctor on the expedition but instead relied on Lewis and Clark. Lewis studied under Dr. Benjamin Rush in Philadelphia as well as several other of the nation’s foremost scientists and doctors. On the expedition, he carried two chests full of medicines. You can view a replica of such a chest equipped with the medicines and medical equipment the Corps would have carried.

Rush’s Thunderclap pills were laxatives containing mercury. Scientists have found Lewis and Clark camp sites in Montana and Idaho based on the mercury deposits they discovered on the soil of the former latrines.

Native tribes introduced the Corps to native plants and animals for food and medicinal purposes. Lewis had learned this technique from his mother who was a herbalist. She used plants from her garden and the woods to treat the sick in Albemarle County, Virginia. On the journey, Lewis gave wild ginger tea to treat colds and made a salve out of bear’s oil, beeswax, and gunpowder.

Another interactive has cards of different ailments. The challenge is to select a method for treatment. Visitors can choose bleeding, saltpeter, Peruvian bark (contains quinine), sweatbaths, etc.

Stop to watch a 32-minute documentary about Lewis and Clark in the theater.

SECOND FLOOR

On this floor, visitors find mounts placed in action, the way Lewis and Clark would have observed them. This includes a full-sized bison. Signage relates how Indians used the bison which was well suited to life on the plains. These animals trimmed the taller grass and enjoyed wallowing in dust baths to relieve itching. Their calves were nimble at 90 minutes and ran with the herd in a few weeks. The Corps loved bison and ate it all the time.

Other mounts include a black bear and her cub, a bobcat, a wolf, a bull elk, and a grizzly bear that growls at visitors. The bobcat was trapped four miles from the museum while the grizzly was shot six times and kept coming. You can compare black and grizzly bear skulls. You’ll also see a Rocky Mountain goat, a mule deer, and a beaver.

Observe a replica of the grizzly bear claw necklace. It is believed the original necklace was given to Lewis and Clark by an Indian chief. Jefferson sent it to Philadelphia and displayed it in America’s first museum until it closed in 1848. It was “lost” for about 150 years then discovered at Harvard’s Peabody Museum. It had been incorrectly stored with artifacts from the South Pacific.

The expedition fished all along the river. Look for the various types of fish the Corps encountered and read about the methods the Native Americans used to catch them. Lewis & Clark noted 709 kinds of fish including 11 species that were new to science.

BASEMENT

This is the area where children can feel free to explore. They can pop up in holes from the prairie dog town, climb into a tipi, and sit in a canoe. Observe a mounted mule deer, a replica of the blacksmith’s forge, and 1/5 scale models of boats. The map on the floor is based on an original drawing by William Clark.

There is a sculpture map on the wall for the blind. Visitors can feel their way from the Missouri River, over the mountains, down the Columbia River, to the Pacific Ocean. The wood from the Timeless Timber Company, is more than 200 years old. It was recovered from a shipwreck at the bottom of Lake Superior. Artist Terry Hudson made this unique map for the Center.

TRAILS

Take the trail to the 48-foot in diameter Plains Indian Earth Lodge. You can also follow trails through the woods or along the limestone bluffs to the Missouri River Overlook. On the Center’s 2.5 miles of trails across the 79 acres, visitors often find several species of wild animals and birds inhabiting the area. Depending upon the time of day and year, you may spot deer, turkeys, raccoons, or other living creatures.

DETAILS

The Missouri River Basin Lewis & Clark Interpretative Trail and Visitor Center is located at 100 Valmont Drive near Nebraska City, Nebraska. The phone number is (402) 874-9900. Hours vary by season. Summer hours (May 1-September 30) are Monday through Saturday 9:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. and Sunday 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. The rest of the year, the hours are Monday through Saturday 10:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. and Sunday noon to 4:00 p.m. During the winter, the Center is closed Monday and Tuesday. Admissions are adults $5.50, college students and seniors $4.50, students $3.50, children (5 and under) free, and active military and veterans $4.

SIOUX CITY LEWIS AND CLARK INTERPRETATIVE CENTER

This center opened in 2002 to commemorate the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial. It is full of animatronic figures, interactive exhibits, reproductions of military uniforms and equipment, and wonderful hand painted murals. Visitors are invited to get involved by using flip books, stamping stations, a brass-rubbing station, and computers.

Its Keelboat Theatre has three videos on varied expedition themes. The 15 minute film A Visit with William Clark, narrated by Captain Clark, relates the expedition’s goals and the events that occurred. The 30-minute film Searching for York tells the story of York, Clark’s slave, and his contribution to the Corps of Discovery. Two Worlds at Two-Medicine is a 35-minute film about the encounter between expedition members and the Blackfeet tribe where two Blackfeet were killed.

The Center focuses on the events that took place from late July to early September 1804. This involved the illness, death, and burial of Sergeant Charles Floyd, the only member of the Corps to die on the expedition; meetings with Native Americans; and how the Corps dealt with deserter Moses Reed. It was also during this time that a Corps member killed the expedition’s first bison.

The Center adjoins the Betty Strong Encounter Center which deals with the land, rivers, and people of the region. It has photo and art exhibitions, an amphitheater, and areas for outdoor games and events. Its Stanley Evans Auditorium hosts numerous programs ranging from lectures, to theater, movies, and panel discussions. It opened in 2007.

Life-sized bronze sculptures of Plains animals, that the Corps encountered, greet visitors as you approach the Center. The largest is a 2,000-pound bison. Walk around the grounds to view a leaping white-tailed deer, two coyotes, a grizzly bear, a marmot, and an elk. Most impressive is the Spirit of Discovery, a 14-foot bronze sculpture of Lewis and Clark with Lewis’s Newfoundland dog, Seaman. Several gardens display plants the expedition would have encountered. You can’t miss the 30-by-50-foot U.S. flag atop a 150-foot flag pole.

The five animatronic mannequins are outstanding. They are made of silicone with their movements controlled by a computer. Thomas Jefferson instructs Lewis and Clark to search for a direct water route to the Pacific Ocean. He further tells them to observe and record information about the people, natural resources, and obstacles they encounter. Lewis and Clark give the eulogy at Floyd’s burial. Floyd sits on top of a crate near the river relating his experience with the expedition. Seaman barks at a prairie dog and wags his tail.

Lewis and Clark had wanted to meet with representatives from the Omaha tribe. However, they never found these Native Americans. The Omahas had been ravaged by smallpox and may have deliberately avoided the Corps. Instead, Lewis and Clark had a council with the Otoes and Missouris. President Jefferson was curious about Indian cultures and instructed them to find out about their languages, traditions, foods, and trade goods.

Moses Reed was supposed to return to camp to retrieve a knife but ended up stealing a rifle and ammunition then deserting. He was returned to camp two days before Floyd’s death and court martialed on August 18, 1804. His punishment was to run a gauntlet four times, suffering up to 500 whip lashes. The soldiers had to hit him or be punished themselves. He returned to St. Louis on the keelboat and was then discharged.

Learn about medicine on the trip. Most remedies were aimed at cleansing the body of “unhealthy fluids” via laxatives and emetics (induced vomiting). Bloodletting was also popular. You’ll see a case with such items as a bleeding bowl, saw for amputations, bullet probe for extracting a lead ball from a gunshot wound, and tooth key for pulling teeth.

Another display features weaponry with a 1792/94 contract rifle, 1795 musket with bayonet, musket balls, and a soldier’s knapsack.

Animals are represented by a prairie rattlesnake, bison skull, and pronghorn antelope skull and horns. In the plant room, visitors discover framed paintings of 20 plants the Corps would have found.

You will learn more about the keelboat. Corporal Richard Warfington was entrusted with returning the boat. On its return to St. Louis, the boat picked up Arikara, Sioux, Omaha, Otoe, and Missouri chiefs who had agreed to meet with President Jefferson. It carried other cargo besides soil, plant, mineral, and animal specimens such as maps, journals, and Indian materials.

It also carried a live prairie dog listed as “a living, burrowing squirrel of the prairie.” The crew kept the animal alive and in captivity until April 1805 when it was sent to President Jefferson. It was later sent to Philadelphia’s Museum of Natural History to be exhibited.

Visitors will enjoy the flip books. One is on York’s contributions. Another on dead reckoning provides exercises you can do. A third is on encountering the Otoes.

One segment of the Center focuses on traditional games. It includes more than two dozen traditional Lakota games presented by Lakota artist Mike Marshall of Rosebud, South Dakota. The Buffalo Robe exhibit highlights the role of the buffalo to Native Americans. The buffalo was the primary source of food, clothing, and shelter for Native Americans. It was also central to traditional beliefs and rituals of many Indian groups.

A Wall of Honor lists the contributions of each member of the Corps as well as Sacagawea; her French-Canadian husband, Toussaint Charbonneau; and their son, born during the expedition, Jean Baptiste.

One popular fun activity is to decide on your role in the expedition. You can be Lewis, Clark, York, a boatman, a private, a sergeant, etc. Your tasks are described. You decide what you want to be and that is your first stamp. At each of the next six exhibits, everyone receives the same stamp regardless of the occupation they choose. Your last stamp is Seaman’s paw print.

CHARLES FLOYD

Charles Floyd was born in Kentucky around 1782. He joined the Corps in 1803 attending to the Captains’ quarters and the expedition’s stores while at Camp DuBois. He was one of three sergeants on the expedition.

On July 31, he complained of being sick but felt better the next day. On August 19, he fell ill again and never recovered, dying on August 20. Lewis called it bilious colic, but it’s likely he suffered a ruptured appendix. In the 1800's, this ailment was an automatic death sentence. Floyd was the only member of the expedition to die and the first United States soldier to die west of the Mississippi River.

He was buried on top of Floyd’s Bluff with full Honors of War. A cedar post marked the spot. Two years later, when the expedition returned, the men visited the site and found the grave had been disturbed. They restored the grave and replaced the fallen marker. In the years that followed, the Missouri River eroded the bluff and the end of the grave, washing away the cedar post.

In 1857, concerned citizens placed the remains they found in a walnut coffin. They buried it 600 feet back from the river and marked the grave. In 1893, Floyd’s journal, which he had kept his entire time with the Corps, was found. When it was published in 1894, it renewed interest in the soldier and his gravesite. The grave had been obliterated by cattle trampling on it and souvenir hunters removing the wooden markers. It was located after considerable effort on Memorial Day 1895.

His remains were placed in two earthenware urns and reburied on August 20, 1895. A marble slab was placed over the grave. The Floyd Memorial Association was formed that year to honor him with a permanent monument. Construction took about a year with work done by the Army Corps of Engineers.

The structure was dedicated May 30, 1901. It’s a 100-foot tall obelisk of Kettle River sandstone, resembling the Washington Monument in Washington, D.C. It’s located at a park overlooking the Missouri River. The monument was the first National Historic Landmark designated by the National Park Service and the United States Department of the Interior. The Center has a 20-foot model of this monument.

Following Floyd’s death, Lewis and Clark wanted Patrick Gass to assume Floyd’s post and rank of sergeant.The Corps held an election, and their endorsement was confirmed. This was the first election west of the Mississippi River. Upon Lewis’s recommendation, Floyd was awarded a land grant that was deeded to his brothers and sisters.

DETAILS

The Center is located at 900 Larsen Park Road, exit 149 off I-29. The phone number is (712) 224-5242. Admission is free. Hours are 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m., Tuesday through Friday, and from noon to 5:00 p.m. on Saturday and Sunday. It is closed on Mondays.

The Sergeant Floyd Monument is found at 2601 S. Lewis Boulevard in Sioux City, Iowa. It is open 24 hours a day.

The Lewis and Clark Historic Trail, which is approximately 4,900 miles long, extends over 16 states from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania to the mouth of the Columbia River near present day Astoria, Oregon. Congress established the trail in 1978 as one of four original national historic trails. Along it, many sites, including several visitor centers, beckon to visitors. We explored three of them in Nebraska and Iowa.

NATIONAL HEADQUARTERS OF THE LEWIS AND CLARK TRAIL

The national headquarters for the trail is in Omaha, Nebraska at the National Park Service’s Midwest Regional Office. The building, which houses a public visitor center, was dedicated in 2004 during the expedition’s 200th anniversary celebration.

The Center is the place to obtain brochures on sites along the trail, the national parks, and Omaha. You can shop its bookstore, watch the 28-minute film Lewis and Clark - Corps of Discovery, ask rangers questions, and request assistance with trip planning.

Signboards and a few cases of artifacts add to your visit. This includes a variety of pelts and parts of a bison. Native Americans used all of the bison from the bladder to the hide. You’ll also spot a grizzly pelt and skull. Grizzlies were encountered numerous times by the Corps.

One signboard mentions the five kinds of weaponry the Corps used for defense and their daily hunt for food. It explains muskets, an air rifle, a swivel gun, a blunderbuss, and lead canisters.

The air rifle, Lewis’s own weapon, was demonstrated at Native American council meetings. A swivel gun was a small bronze cannon located on the keelboat’s bow while blunderbusses (heavy shotguns) were on the stern. Blunderbusses were fired for three reasons: signaling, saluting, and celebrations. Lead canisters served two purposes. They each held four pounds of gun powder. Composed of sheet lead, the cans could be melted down and used for bullets.

Another sign describes transportation. The Corps employed bull boats, an iron boat, pirogues, a keelboat, dugout canoes, and horses. Bull boats were made of bison hides stretched over a wooden frame. Pine pitch was used to make the vessels watertight. Horses acquired from the Shoshones enabled the Corps to cross the Rocky Mountains. The Nez Perce taught the Corps to use fire to build canoes from cottonwood and pine trees. These dugouts were up to 33 feet long.

The 200-pound collapsible iron boat was Lewis’s invention. The Corps failed to seal the hides by covering it with tar, causing the boat to sink. This led Clark to design a cart that moved supplies and the other boats overland.

Before leaving on the expedition, Meriwether Lewis shopped in Philadelphia for many of the supplies he would need on the trip including those for mapping. The cartography case includes reproductions of a magnet, needles, and two compasses Lewis would have purchased in 1803.

Many items used on the expedition were lost or destroyed on the journey. However, a silver-plated pocket compass Lewis had bought became his keepsake and ended up in the Smithsonian.

In the same case, you can also see a replica of a map Clark made. He was the first to map the Missouri River in its entirety as well as the Northwest. His maps were used, because of their accuracy, by many who came after him. In 4,000 miles, Clark was only off by 40 miles in his calculations.

The case of trade goods consists of reproductions of a Sioux tobacco pouch, chief’s hat from Fort Clatsop, and wampum purchased by Lewis in 1803. The Corps of Discovery purchased a canoe with a 36-foot strand of wampum beads.

Lewis asked two Clatsop women to make hats for them. Since they were tightly woven of cedar and bear grass and because of their shape, the hats were rain repellent. With the Mandans, the Corps traded medical services and metal artifacts for the corn and other produce the tribe still grows today.

One of the goals of the expedition was to collect animal and plant specimens to send back to Jefferson. A case at the Center houses taxidermied specimens similar to those collected on the trip. You can see a a Yellow-bellied marmot from Idaho and a long-tailed weasel from North Dakota.

Last year, ranger programs occurred in the morning and afternoon during summer months on most days. However, due to decreased staff, the programs were discontinued this year. The Center hopes to resume them in 2020.

DETAILS

During the summer, this visitor center is open daily while during the winter, it is closed on weekends. Summer hours are Monday through Friday from 8:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. and on weekends from 9:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Winter hours are Monday through Friday from 8:00 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Admission is free. The address is 601 Riverfront Drive in Omaha. The phone number is (402) 661-1804. For more information, go to their web site.

MISSOURI RIVER BASIN - LEWIS AND CLARK INTERPRETATIVE TRAIL & VISITOR CENTER

What makes this Center near Nebraska City, Nebraska different from all other museums and centers along the Trail is its unique focus on the Corps of Discovery’s flora, fauna, and scientific discoveries recorded in the journals of Lewis and Clark. You’ll learn about the animals, birds, fish, plants and medicine of the expedition. On three floors, numerous interactive exhibits, superb mounted species in quality dioramas, and bird calls make this an enjoyable experience. During the second Saturday of each month during the summer, the Center has reenactors.

Before entering, step on board a full sized replica of the keelboat Lewis and Clark used. The 55-foot keelboat was 8 feet 4 inches in width. It drew two to 2.5 feet of water when loaded with an estimated 12 to 15 tons of supplies. An enclosure at the stern was Clark’s office. He was responsible for maps and journals.

Built in Pittsburgh, to Lewis’s specifications, it traveled down the Ohio River, picking up Clark in Kentucky. It continued down the Ohio River then up the Mississippi River to the mouth of the Missouri River near St. Louis. On May 21, 1804, the keelboat and two pirogues set out from St. Charles with a crew of 44.The Corps used the keelboat on the expedition until they reached the Mandan village in North Dakota during November of 1804. After Lewis and Clark loaded it with specimens of plants and animals to be sent to President Jefferson, the boat and its crew of 12 men left Fort Mandan on April 2, 1805. That was the same day the permanent party headed west in the pirogues. The keelboat reached St. Louis on May 20, 1805.

The Center’s replica was used as a movie prop for the IMAX movie Lewis and Clark: The Great Journey West. It is unsure that the replica follows the original plan because historians don’t know whether the historical boat’s keel was round or flat. Most think it was round.

Inside the Center, note the sculpture of Thomas Jefferson titled The Naturalist. It greets people at the entrance and was sculpted by Carol A. Grende.

There is also a sculpture of Seaman, who was Lewis’s Newfoundland dog. He saved Lewis’s life twice. He got between him and an 8-1/2 foot grizzly and diverted a bison bull from camp. He also was excellent at hunting squirrels, beavers, and even antelope.

You’ll see a mural of the Nebraska City area in 1804 when trees only grew along the river. Nebraska City became a supply center, a stopping point on the river, that at one time was larger than Omaha. When the transcontinental railroad was built through Omaha/Council Bluffs, Nebraska City lost traffic and the population fell from 12,000 to 5,000.

Inside the Center, visitors find a reproduction of a 32-foot, white pirogue (long, narrow riverboat). It’s the smaller of two pirogues, the other of which was red, used on the expedition to Great Falls, Montana where the Corps made canoes. The only true sketch of the white pirogue was done by Clark in Illinois during the winter of 1803-1804 when he estimated how much equipment the boats could carry.

The white pirogue was to return the first summer with dispatches for President Jefferson. Instead, it traveled further than the other boats and returned to St. Louis in September 1806 as the command vessel. The one at the museum was built in 1999 for the same movie as the keelboat.

Like the original boat, this one was constructed of poplar planks. The original had a stern tiller, a mast, and sails. The men sometimes stretched an awning over the stern to provide shade. Six oarsmen rowed it standing up. A bowman was posted in front to watch for snags and sandbars. A helmsman, in the rear, steered using a tiller as a rudder.

They didn’t always row the boat to propel it. If the wind was right, they used the sails. They also sometimes used poles to push against the river bottom or tied ropes to the boats and towed them along. Youngsters are allowed to board this vessel and pretend to steer it. Look for the badger and cinnamon bear pelts on board.

One interactive is fascinating and I could have spent hours on it. The Center has listed on cards all of the 300 new plants (178) and animals (122) that Lewis and Clark discovered during their expedition. Each card has a picture and notes where each species was encountered, the date, and its natural habitat.

An interactive touchscreen exhibit allows visitors to experience sights and sounds while viewing the migratory territories of each bird species recorded by Lewis and Clark. While hiking the Center’s trails, you’re likely to view many bird varieties along the flyway between Canada and South America.

A third interactive is about dead reckoning. You can estimate how far you are from points by using your vision.

As we learned in Omaha, very few artifacts remain from the expedition. Most are replicas. For example, the captain’s tent you’ll see reveals the size they would have used.

At another interactive, you can scan in cards to learn what plants the Corps discovered on the trail and how they used them. For example, the exceptionally strong wood of the osage orange tree was used for bows and arrows. You’ll find this plant along the trails surrounding the Center.

One exhibit deals with medicine. Jefferson did not send a doctor on the expedition but instead relied on Lewis and Clark. Lewis studied under Dr. Benjamin Rush in Philadelphia as well as several other of the nation’s foremost scientists and doctors. On the expedition, he carried two chests full of medicines. You can view a replica of such a chest equipped with the medicines and medical equipment the Corps would have carried.

Rush’s Thunderclap pills were laxatives containing mercury. Scientists have found Lewis and Clark camp sites in Montana and Idaho based on the mercury deposits they discovered on the soil of the former latrines.

Native tribes introduced the Corps to native plants and animals for food and medicinal purposes. Lewis had learned this technique from his mother who was a herbalist. She used plants from her garden and the woods to treat the sick in Albemarle County, Virginia. On the journey, Lewis gave wild ginger tea to treat colds and made a salve out of bear’s oil, beeswax, and gunpowder.

Another interactive has cards of different ailments. The challenge is to select a method for treatment. Visitors can choose bleeding, saltpeter, Peruvian bark (contains quinine), sweatbaths, etc.

Stop to watch a 32-minute documentary about Lewis and Clark in the theater.

SECOND FLOOR

On this floor, visitors find mounts placed in action, the way Lewis and Clark would have observed them. This includes a full-sized bison. Signage relates how Indians used the bison which was well suited to life on the plains. These animals trimmed the taller grass and enjoyed wallowing in dust baths to relieve itching. Their calves were nimble at 90 minutes and ran with the herd in a few weeks. The Corps loved bison and ate it all the time.

Other mounts include a black bear and her cub, a bobcat, a wolf, a bull elk, and a grizzly bear that growls at visitors. The bobcat was trapped four miles from the museum while the grizzly was shot six times and kept coming. You can compare black and grizzly bear skulls. You’ll also see a Rocky Mountain goat, a mule deer, and a beaver.

Observe a replica of the grizzly bear claw necklace. It is believed the original necklace was given to Lewis and Clark by an Indian chief. Jefferson sent it to Philadelphia and displayed it in America’s first museum until it closed in 1848. It was “lost” for about 150 years then discovered at Harvard’s Peabody Museum. It had been incorrectly stored with artifacts from the South Pacific.

The expedition fished all along the river. Look for the various types of fish the Corps encountered and read about the methods the Native Americans used to catch them. Lewis & Clark noted 709 kinds of fish including 11 species that were new to science.

BASEMENT

This is the area where children can feel free to explore. They can pop up in holes from the prairie dog town, climb into a tipi, and sit in a canoe. Observe a mounted mule deer, a replica of the blacksmith’s forge, and 1/5 scale models of boats. The map on the floor is based on an original drawing by William Clark.

There is a sculpture map on the wall for the blind. Visitors can feel their way from the Missouri River, over the mountains, down the Columbia River, to the Pacific Ocean. The wood from the Timeless Timber Company, is more than 200 years old. It was recovered from a shipwreck at the bottom of Lake Superior. Artist Terry Hudson made this unique map for the Center.

TRAILS

Take the trail to the 48-foot in diameter Plains Indian Earth Lodge. You can also follow trails through the woods or along the limestone bluffs to the Missouri River Overlook. On the Center’s 2.5 miles of trails across the 79 acres, visitors often find several species of wild animals and birds inhabiting the area. Depending upon the time of day and year, you may spot deer, turkeys, raccoons, or other living creatures.

DETAILS

The Missouri River Basin Lewis & Clark Interpretative Trail and Visitor Center is located at 100 Valmont Drive near Nebraska City, Nebraska. The phone number is (402) 874-9900. Hours vary by season. Summer hours (May 1-September 30) are Monday through Saturday 9:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. and Sunday 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. The rest of the year, the hours are Monday through Saturday 10:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. and Sunday noon to 4:00 p.m. During the winter, the Center is closed Monday and Tuesday. Admissions are adults $5.50, college students and seniors $4.50, students $3.50, children (5 and under) free, and active military and veterans $4.

SIOUX CITY LEWIS AND CLARK INTERPRETATIVE CENTER

This center opened in 2002 to commemorate the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial. It is full of animatronic figures, interactive exhibits, reproductions of military uniforms and equipment, and wonderful hand painted murals. Visitors are invited to get involved by using flip books, stamping stations, a brass-rubbing station, and computers.

Its Keelboat Theatre has three videos on varied expedition themes. The 15 minute film A Visit with William Clark, narrated by Captain Clark, relates the expedition’s goals and the events that occurred. The 30-minute film Searching for York tells the story of York, Clark’s slave, and his contribution to the Corps of Discovery. Two Worlds at Two-Medicine is a 35-minute film about the encounter between expedition members and the Blackfeet tribe where two Blackfeet were killed.

The Center focuses on the events that took place from late July to early September 1804. This involved the illness, death, and burial of Sergeant Charles Floyd, the only member of the Corps to die on the expedition; meetings with Native Americans; and how the Corps dealt with deserter Moses Reed. It was also during this time that a Corps member killed the expedition’s first bison.

The Center adjoins the Betty Strong Encounter Center which deals with the land, rivers, and people of the region. It has photo and art exhibitions, an amphitheater, and areas for outdoor games and events. Its Stanley Evans Auditorium hosts numerous programs ranging from lectures, to theater, movies, and panel discussions. It opened in 2007.

Life-sized bronze sculptures of Plains animals, that the Corps encountered, greet visitors as you approach the Center. The largest is a 2,000-pound bison. Walk around the grounds to view a leaping white-tailed deer, two coyotes, a grizzly bear, a marmot, and an elk. Most impressive is the Spirit of Discovery, a 14-foot bronze sculpture of Lewis and Clark with Lewis’s Newfoundland dog, Seaman. Several gardens display plants the expedition would have encountered. You can’t miss the 30-by-50-foot U.S. flag atop a 150-foot flag pole.

The five animatronic mannequins are outstanding. They are made of silicone with their movements controlled by a computer. Thomas Jefferson instructs Lewis and Clark to search for a direct water route to the Pacific Ocean. He further tells them to observe and record information about the people, natural resources, and obstacles they encounter. Lewis and Clark give the eulogy at Floyd’s burial. Floyd sits on top of a crate near the river relating his experience with the expedition. Seaman barks at a prairie dog and wags his tail.

Lewis and Clark had wanted to meet with representatives from the Omaha tribe. However, they never found these Native Americans. The Omahas had been ravaged by smallpox and may have deliberately avoided the Corps. Instead, Lewis and Clark had a council with the Otoes and Missouris. President Jefferson was curious about Indian cultures and instructed them to find out about their languages, traditions, foods, and trade goods.

Moses Reed was supposed to return to camp to retrieve a knife but ended up stealing a rifle and ammunition then deserting. He was returned to camp two days before Floyd’s death and court martialed on August 18, 1804. His punishment was to run a gauntlet four times, suffering up to 500 whip lashes. The soldiers had to hit him or be punished themselves. He returned to St. Louis on the keelboat and was then discharged.

Learn about medicine on the trip. Most remedies were aimed at cleansing the body of “unhealthy fluids” via laxatives and emetics (induced vomiting). Bloodletting was also popular. You’ll see a case with such items as a bleeding bowl, saw for amputations, bullet probe for extracting a lead ball from a gunshot wound, and tooth key for pulling teeth.

Another display features weaponry with a 1792/94 contract rifle, 1795 musket with bayonet, musket balls, and a soldier’s knapsack.

Animals are represented by a prairie rattlesnake, bison skull, and pronghorn antelope skull and horns. In the plant room, visitors discover framed paintings of 20 plants the Corps would have found.

You will learn more about the keelboat. Corporal Richard Warfington was entrusted with returning the boat. On its return to St. Louis, the boat picked up Arikara, Sioux, Omaha, Otoe, and Missouri chiefs who had agreed to meet with President Jefferson. It carried other cargo besides soil, plant, mineral, and animal specimens such as maps, journals, and Indian materials.

It also carried a live prairie dog listed as “a living, burrowing squirrel of the prairie.” The crew kept the animal alive and in captivity until April 1805 when it was sent to President Jefferson. It was later sent to Philadelphia’s Museum of Natural History to be exhibited.

Visitors will enjoy the flip books. One is on York’s contributions. Another on dead reckoning provides exercises you can do. A third is on encountering the Otoes.

One segment of the Center focuses on traditional games. It includes more than two dozen traditional Lakota games presented by Lakota artist Mike Marshall of Rosebud, South Dakota. The Buffalo Robe exhibit highlights the role of the buffalo to Native Americans. The buffalo was the primary source of food, clothing, and shelter for Native Americans. It was also central to traditional beliefs and rituals of many Indian groups.

A Wall of Honor lists the contributions of each member of the Corps as well as Sacagawea; her French-Canadian husband, Toussaint Charbonneau; and their son, born during the expedition, Jean Baptiste.

One popular fun activity is to decide on your role in the expedition. You can be Lewis, Clark, York, a boatman, a private, a sergeant, etc. Your tasks are described. You decide what you want to be and that is your first stamp. At each of the next six exhibits, everyone receives the same stamp regardless of the occupation they choose. Your last stamp is Seaman’s paw print.

CHARLES FLOYD

Charles Floyd was born in Kentucky around 1782. He joined the Corps in 1803 attending to the Captains’ quarters and the expedition’s stores while at Camp DuBois. He was one of three sergeants on the expedition.

On July 31, he complained of being sick but felt better the next day. On August 19, he fell ill again and never recovered, dying on August 20. Lewis called it bilious colic, but it’s likely he suffered a ruptured appendix. In the 1800's, this ailment was an automatic death sentence. Floyd was the only member of the expedition to die and the first United States soldier to die west of the Mississippi River.

He was buried on top of Floyd’s Bluff with full Honors of War. A cedar post marked the spot. Two years later, when the expedition returned, the men visited the site and found the grave had been disturbed. They restored the grave and replaced the fallen marker. In the years that followed, the Missouri River eroded the bluff and the end of the grave, washing away the cedar post.

In 1857, concerned citizens placed the remains they found in a walnut coffin. They buried it 600 feet back from the river and marked the grave. In 1893, Floyd’s journal, which he had kept his entire time with the Corps, was found. When it was published in 1894, it renewed interest in the soldier and his gravesite. The grave had been obliterated by cattle trampling on it and souvenir hunters removing the wooden markers. It was located after considerable effort on Memorial Day 1895.

His remains were placed in two earthenware urns and reburied on August 20, 1895. A marble slab was placed over the grave. The Floyd Memorial Association was formed that year to honor him with a permanent monument. Construction took about a year with work done by the Army Corps of Engineers.

The structure was dedicated May 30, 1901. It’s a 100-foot tall obelisk of Kettle River sandstone, resembling the Washington Monument in Washington, D.C. It’s located at a park overlooking the Missouri River. The monument was the first National Historic Landmark designated by the National Park Service and the United States Department of the Interior. The Center has a 20-foot model of this monument.

Following Floyd’s death, Lewis and Clark wanted Patrick Gass to assume Floyd’s post and rank of sergeant.The Corps held an election, and their endorsement was confirmed. This was the first election west of the Mississippi River. Upon Lewis’s recommendation, Floyd was awarded a land grant that was deeded to his brothers and sisters.

DETAILS

The Center is located at 900 Larsen Park Road, exit 149 off I-29. The phone number is (712) 224-5242. Admission is free. Hours are 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m., Tuesday through Friday, and from noon to 5:00 p.m. on Saturday and Sunday. It is closed on Mondays.

The Sergeant Floyd Monument is found at 2601 S. Lewis Boulevard in Sioux City, Iowa. It is open 24 hours a day.

National Headquarters of the Lewis and Clark Trail

Variety of Pelts Representing Animals Lewis and Clark Would Have Seen

Grizzly Bear Skull

Cartography Case

Trade Goods Case

Missouri River Basin - Lewis and Clark Interpretative Trail and Visitor Center

Replica From IMAX Movie of Lewis and Clark's Keelboat

Statue of Thomas Jefferson The Naturalist by C. A. Grende

Replica of White Pirogue

Replica of Lewis's Medicine Chest

Bison - A Vital Animal to the Native Americans

Trapped Four Miles From the Museum

Grizzly Shot at Six Times and Just Kept Coming

Grizzly Bear Claw Necklace

Children Can Climb Into the Tipi and Canoe in the Museum's Basement Level

Children Enjoy Popping In and Out of the Groundhog Holes

Sioux City Lewis and Clark Interpretative Center With Betty Strong Encounter Center in Background

Spirit of Discovery by Pat Kennedy

One of the Visitor Center's Many Animal Sculptures

Thomas Jefferson - Animatronic Figure

Lewis and Clark Animatronic Figures at Floyd's Burial

Seaman, Lewis's Dog - Another Animatronic Figure

Mural of Moses Reed's Court Martial

Medicine on the Trail

Tribute to Some of the Plants Lewis and Clark Found

Wall of Honor Listing Expedition Members

Floyd Monument in Sioux City, Iowa