Hello Everyone,

Travelers to Mitchell find it offers more than the Corn Palace. The Dakota Discovery Museum combines art, history, and historic buildings. Mitchell Prehistoric Indian Village is an active archaeological site tracing a civilization from around 1,000 A.D. At Hansen Wheel and Wagon Shop, staff does sales, restorations, and custom work on all kinds of horse drawn carriages.

DAKOTA DISCOVERY MUSEUM

In 1939, Friends of the Middle Border founded a museum which later became the Dakota Discovery Museum. It has always been housed on the Dakota Wesleyan University campus.

On the second floor, you will find art galleries. The main level is dedicated to the Middle Border region (North Dakota, South Dakota, and parts of adjoining spaces) from the early days of the Dakota Territory to the 1930s. On the museum’s grounds, you can view four historic buildings.

Upstairs, you find three galleries. The Leland and Josephine Case Gallery features an original painting by Harvey Dunn entitled Dakota Woman. However, much of that space is used for changing exhibits. A second is devoted to numerous Oscar Howe paintings. Howe was recognized for revolutionizing Native American art.

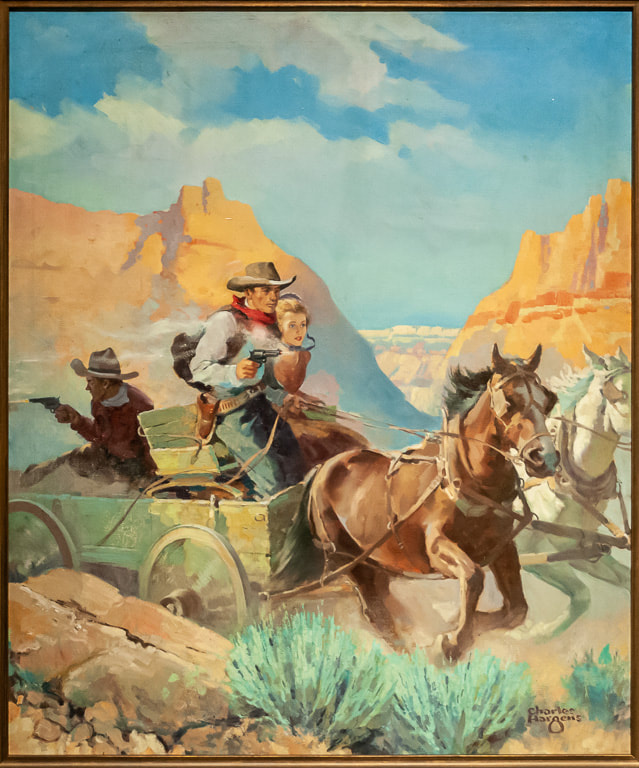

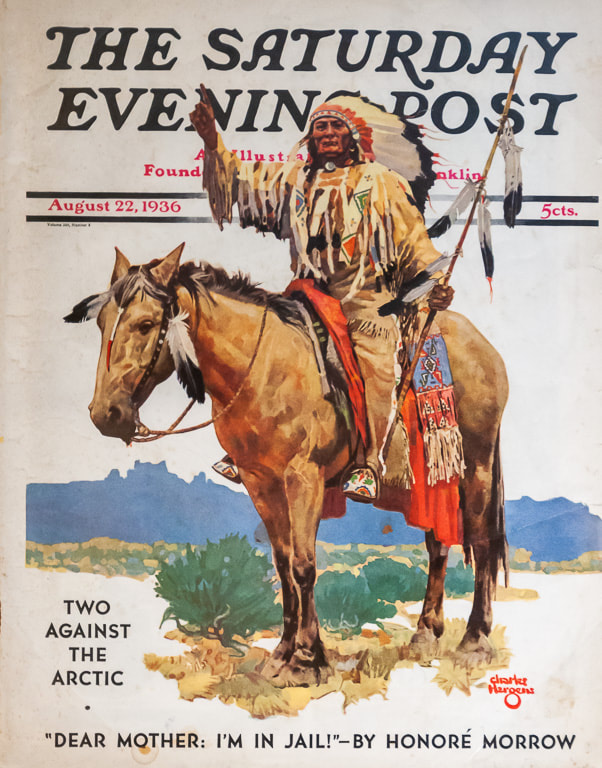

A third is the Charles Hargens Gallery. He was known for his western illustrations capturing life in the West. Most of his illustrations were painted in oil on canvas although he also used pen and ink and tempera on paper.

The magazines for which he did illustrations include The Saturday Evening Post, Collier's, McClure's, Liberty, Gentleman's Quarterly, and Boys Life. He worked on book jackets, magazine illustrations, and advertisements for the Stetson Hat Company and Coca Cola and designed posters for ten years for the Multiple Sclerosis Society. In all, he illustrated more than 300 books and 3,000 magazines.

When he died in 1957, his family honored his wish that his Carversville art studio and many of his Western works be donated to the Dakota Discovery Museum. See these in this gallery today.

Downstairs, visitors explore, through a series of scenes, the traditions of the Plains Indians and early American settlers through life during the 1930s Great Depression. Note the extensive collection of Native American beadwork, an authentic tipi, and a conestoga wagon. Check out information on the Plains Indians as well as the fur trade. A claim shanty represents the Homestead Settlement Act. Commerce in the 1860s covers railroading and ranching. Another reveals the importance of agriculture to the state. The exhibit on the Great Depression of the 1930s includes a replica of Everett F. Cotton’s watch repair shop.

OUTSIDE THE MUSEUM

The historic village contains four buildings. It is reached by going out the front door and walking around the building. Due to lack of staff, guided tours of these buildings are at a minimum.

The 1886 Beckwith House was built by Louis and Mary Beckwith. He and L. O. Gale co-founded the Mitchell Corn Palace. The home was originally located in uptown Mitchell and is on the National Register of Historic Places. It was known as one of the town’s social places.

The home is of Italianate architecture with Queen Anne details such as a bay window, fish scale shingles, fretwork, and porch posts. Its original exterior colors of sage and dark sage with oxblood red accents are visible today. Many original furnishings remain in the home along with collections of the Beckwith clothing, memorabilia, and handmade needlework.

Built in 1884, the Sheldon County School was on land in another county. The property was donated by Millard Sheldon who constructed it. Patricia Geddes taught the first class in the spring of 1885. The school didn’t provide books so children brought their own from previous schools, borrowed them from parents or siblings, or shared books with other students.

The school also served as a community center with a lyceum conducted every two weeks during the winter. Community members provided recitations, music, and short plays. A debate on a current topic followed a short intermission. It closed in 1944-45 and was moved in 1965 to the museum grounds.

The Farwell Church congregation, organized in 1880, was assigned a regular preacher in 1883. The building, constructed during1908/1909, was originally located 16 miles northeast of Mitchell. It came to the museum in 1989. Its pews are original as is the basic building shape. Renovations have been made to the nave, ceilings, and dividing wall depending upon the congregation’s needs. It has been restored and is available for weddings and Sunday services with all denominations welcome.

When the Milwaukee Road built a railroad between Scotland Junction and Mitchell in 1886, Dimock was one of the stations. This depot dates to 1914 with Charles A. Johnson as agent. When he retired in 1963, the depot was then used on a part time basis by the agent from Parkston. In July 1971,the South Dakota Public Utilities Commission closed and removed the station. It was donated to the museum in 1973.

DETAILS

The address is 1300 McGovern Ave, Mitchell. The telephone number is (605) 996-2122. The museum is currently closed because of the corona virus. Normal hours are Monday through Friday from 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Admissions are seniors (63+) $6, adults $7, youth (ages 6-17) $3, and free under age six.

MITCHELL PREHISTORIC INDIAN VILLAGE

A LITTLE HISTORY

The Mitchell Prehistoric Indian Village is the only archaeological site in South Dakota open to the public. It is located on the bluff above Firesteel Creek near Mitchell. A Dakota Wesleyan University student discovered the site in 1910. W. H. Over, based at the University of South Dakota, mapped it for the first time in 1922.The bluff’s edges started to erode when the valley containing the creek was dammed in 1928 to create Lake Mitchell. During 1937 and 1938, a crew funded by the Works Progress Administration excavated two of the earth lodge depressions.

Dr. Robert Alex, from the University of Wisconsin, did the next professional archaeological work at the Mitchell site in 1970-71. He discovered a lodge whose evidence showed it was destroyed by fire but included remarkable architectural detail. In 1975, the Mitchell Prehistoric Indian Village Preservation Society formed to preserve the site.

In 1983, the Archaeology Lab at Augustana College in Sioux Falls, South Dakota assumed responsibility for the research and creation of an interpretative museum at the site. They were joined in 2003 by the Department of Archaeology at University of Exeter, Exeter, England. Now students from both schools come every summer for the site’s Summer Archaeology Field School.

The Village is special because it is one of the few sites in pristine condition in the Northern Plains that was never plowed or had any significant disturbance. It was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1964.

The public can visit the Boehnen Memorial Museum at the site and watch an active dig during the summer inside the Thomsen Center Archeodome. When funding allows, excavations take place year round. A laboratory and exhibits are also found in the Archeodome. In the museum, visitors discover a full-size reproduction of an earthen lodge, a bison skeleton, and cases of many artifacts found at the site. It’s the location for Shoppe Antiquary, which is the gift shop, and a video on the village.

WHY THIS SITE

Archaeologists believe these ancient people selected this site for a number of reasons. It was close to water which was necessary for drinking and cooking. During the dry times, they could water their crops. The creek also supplied fish and clams.

Since the site was on a bluff, it could serve as a defense against other tribes or against flooding. A palisade in the southwest portion of the village also helped protect it as did a ditch. Since lots of timber exists along riverbanks, the Indians had a good supply of wood to build and heat their homes, fire pottery, and use for such tools as spears and arrows.

WHO WERE THESE PEOPLE

They migrated to the Mitchell site from between 975 and 1100 AD from the eastern edge of what is now Minnesota/Iowa. Why they left is uncertain, but one plausible reason is that they ran out of natural resources, particularly timber. The evidence points to them eventually moving to North Dakota. The Mandans that Lewis and Clark discovered are likely descendants of these people.

They were farmers, gatherers, and hunters, particularly of bison but also of elk and deer. This was done on foot or by driving herds of bison over cliffs or into corrals. When animals were scarce, they survived on the food they grew. Various types of carbonized seeds and corn cobs show the villagers planted corn, soybeans, squash, beans, tobacco, and sunflowers. Corn was eaten fresh, dried, ground in wooden mortars, or leeched to produce hominy. The Amaranthus, a grain crop, was also grown.

They lived as extended families in rectangular shaped, earthen lodges resembling upside down baskets. These were 20 x 40 foot structures, not simultaneously built, housing 12 to 15 people. It is estimated 70 to 80 lodges are buried on the grounds that were homes to 500 to 800 people.

A mixture of mud, clay, or grass was plastered over the framework. Walls were about a foot thick. They had at least one fire ring or hearth for warmth and cooking though most of the cooking was done outdoors. The fire ring implies the presence of a smoke hole in the roof to keep smoke and toxic gases from building up in the home. Almost every lodge had an exterior storage pit large enough to accommodate the bushels of crops they grew.

They used tools similar to those of later tribes. These were made of bone, ceramic, shell, and stone materials. Many were used for farming such as bone hoes, sickles, squash knives, and deer antler rakes. Larger arrow points may have been used as knives, spears, or scrapers. Specially shaped ones could be used as drills, axes, or hammers.

Bone artifacts, mainly from bison, have been found in great numbers at the Mitchell site. Deer bones and those from smaller animals have also been discovered. These included long narrow and pointed awls. Awls were used for piercing holes for purposes such as sewing. Squash knives were made from a bison’s scapula. Utensils were fashioned from antlers and bones. Other bones were used for cutters, scrapers, and fishhooks.

To cook their foods, stones heated in the fire were dropped in round bottom pots containing water. Pots weren’t placed on the fire directly. Decorations were often drawn on the pot’s surface by using a pointed object, perhaps of wood or stone. Pottery, seeds, and foodstuffs were among the most actively traded items.

In 2015, on the site’s Archaeology Awareness Days, the excavation team found the first ever unbroken ceramic vessel. All pottery before that, since 1910, had been in pieces. Fortunately, archaeologists could form a complete impression from a pot’s fragment.

You can see a “bull-boat” at the Archeodome. They were constructed by stretching the hide of a bull bison over a wooden frame of branches. They hauled people and goods. Sometimes they were strung together to support large loads. Look for the dog and travois in the museum. Dogs were used to haul goods before the Spanish brought horses.

Weaponry improved because of trade. Early spears and lances gave way to spear-throwers and atlatls. Others consisted of bows and arrows and stone knives. Arrowheads, like pottery, reveal the influence of other cultures. Those at the Mitchell site had a variety of styles. They were made from various materials such as flints of different shades.

The site was once a major bison processing center. During the cold months, the bone grease was extracted from bison bones for the manufacture of pemmican. It was then mixed with dried meat pounded almost to a powder, dried grains, and dried chokeberries or other dried berries. It had a shelf life of at least eight years. It was an important trade item for the villagers as well as used for snacks and as a winter food.

Trade networks spread across the continent. Arrow points have been found from Canada, copper from the Great Lakes, and obsidian and lava from regions west of South Dakota. Local mollusk shells and decorative seashells from the Gulf of Mexico have been excavated on the Mitchell site. This indicates they traded with tribes from those areas. Shells were used for decorating clothing or as jewelry. Making beads was common in late Stone Age sites. The Mitchell people produced tubular and flat disc shell beads.

Archaeologists are now employing new tools besides trowels, picks, and brushes. Among these are computers and electron microscopes. Electric resistance, magnetism, and radar are currently used to explore buried sites without digging. It is hoped that radiocarbon dating, soil and mineral analysis, and newer ways to use DNA will increase the knowledge of these scientists.

What won’t be discovered at the site are wood and other vegetable materials. For example, archaeologists find arrow points but no arrows. Post holes exist but no poles. Fibers and skins are also erased by time leaving little evidence of what those at the Mitchell site wore. Only the most durable materials remain - stone, baked clay, and bone.

VISITING THE SITE

In the summer, take a guided tour of the museum and the Archeodome by knowledgeable guides. Look for the chart explaining how each part of the bison was used by those who lived at the site. Visitors also see a diorama of the village and can explore a reconstructed lodge.

The museum’s cases contain lots of items excavated at the Archeodome. These include needles, awls, buttons, arrowheads, and fish hooks. Ask your guide about the Atlatl, the throwing spear. We were fortunate enough to have our guide, Dennis Scott, demonstrate it for us.

On the way to the Archeodome , Dennis pointed out the Flame of Wisdom statue by Leonard Nierman in 1999. Made of stainless steel, it was presented on this building’s dedication.

Audry’s Garden is the newest exhibit. It showcases the native plants that the villagers used for foods, medicines, dyes, and ceremonies, It consists of 36 different species. Flowering occurs from late March through late fall. Information plaques identify each plant and its uses.

The Archeodome, erected in 1999, is one of a handful of enclosed archaeological teaching and research facilities in the country. The exposed earthen floor is where the dig occurs. Exploration occurs where no lodges are known to exist. As of 2018, archaeologists were exploring caches at the four or five-foot level. A wealth of artifacts is expected to be located 10 to 12 feet below today’s ground level. At this rate, according to Dennis, the excavation will take about 50 years. So far, archaeologists have discovered 1.5 million artifacts on the site during the 20 years of excavation.

All findings are placed into pails in ziploc containers to be taken to the laboratory and processed. All bags are numbered. Particular attention is paid to the artifact’s location which is mapped on a grid. Important information about the past may be revealed in minor changes or soil color and texture. For example, areas of light clay may indicate evidence of burrowing animals. Ash concentrations represent materials cleaned out of fire hearths.

At the Archeodome, visitors find cases of artifacts. One includes a bone fish hook, a knife handle, and a projectile point. Another consists of bone tools while a third has chipped stones used as scrapers, drills, projectile points, and knives. Three contain maize. Nearby is a video of the 2017 excavation. Mississippian pottery such as a reconstructed pot and ceramic discs are also on view.

Children enjoy the “Kids Dig” in the Archeodome. They learn how archaeologists sort bone, stone, and ceramic artifacts. They can excavate plastic arrowheads and turn them into the gift shop for a real arrowhead.

SPECIAL EVENTS

In mid-June, the students from Exeter University arrive. You can watch their excavations. Archaeology Days are scheduled for June 27 and 28 in 2020. It’s the site’s biggest event of the year showcasing archaeology awareness, primitive technology, and Native American culture. The second annual Native American Lore and Culture Day will be held July 25, 2020. Visitors learn how to make corn husk dolls, play ancient Lakota games, make pottery, listen to storytellers, and more.

DETAILS:

The Mitchell Prehistoric Indian Village is located at 3200 Indian Village Road in Mitchell. The telephone number is (605) 996-5473. They are closed now because of the virus. They are usually open Monday through Saturday from April to May and September to November 15 from 9:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. with the last tour at 5:30. From Memorial Day to Labor Day, their normal schedule is Monday through Saturday 8:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m. and Sunday 10:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. Admissions are adults $6, seniors (60 up) $5, students (13-18) $4. For ages 12 and under, it’s free.

HANSEN WHEEL AND WAGON SHOP

WHAT DOES THIS COMPANY DO

Have you ever wondered where a lot of horse drawn vehicles you see in museums and living history farms come from? The premier custom builder, restorer, and seller of these vehicles is Hansen Wheel and Wagon Shop. They have worked with stagecoaches, chuck wagons, hitch wagons, freight wagons, and many more. It’s a company motivated by a love of history and a desire to preserve our heritage. The company is rurally located just off SD Highway 37 between Mitchell and Letcher, South Dakota.

Doug Hansen and his wife Holly started the company in 1978. Doug’s mother was a horsewoman who wanted her son to make a hitch for her buggy. She then asked Doug to restore the buggy. He did research at local firms and borrowed tools from them to accomplish this task. He also learned to repair wheels. People from the area starting bringing him their buggies and a business started.

The staff of 12 consists of skilled craftsmen who pay meticulous attention to details. They come with skills then are trained into a special skill: wheelwright, wainwright (wagon builder), painter, or upholsterer. One gentleman does restoration.

“It matters to us to do it right,” said Doug. “That’s what we built our reputation on. But it’s also a responsibility for the craft that we’re representing because if we do it wrong, we’re polluting. It’s not how we do it but how they did it, and that’s what we need to replicate.”

For custom vehicles, their goal is to maintain the durability and style of the original design. At the same time, they incorporate the client’s wishes for design elements.

Restoration starts with careful research and documentation about the original vehicles and makers. For example, the original color, striping, and trim on these vehicles indicate the manufacturer and the era that they were built. These can be sometimes hard to identify because of the erosion of design details.

Hansen Wheel and Wagon Shop craftsmen use authentic materials and construction, adding finishes that define the original maker’s art. They restore the vehicle to look as original as possible. Historic horse-drawn vehicles were once stripped of their original paint, decoration, and trim during the restoration process. It’s now recognized that it’s important to preserve what remains in order to keep the vehicle’s value.

During restoration, craftsmen find blacksmith marks, a serial number, and occasionally a date. At other times, the date is unknown. One manufacturer, Peter Schuttler, stamped a date on his wagons. However, on the Schuttlers, it is unknown if the date applied to when the wagons went into the drying shed or rolled off the assembly line. The earliest Schuttler that Doug worked on was an 1883 freight wagon used at Lead’s Homestake Mine. It was for a museum at Deadwood.

The shop also carries an inventory of more than 40 horse drawn vehicles manufactured between 1850 and 1911. In August of 2018, we visited the wagon barn where a quarter of the vehicles was Hansen’s private collection. Of the remaining ones there, half were in for restoration and half in the inventory for sale.

In addition, to the above, they do axle repair and build and replace wagon wheel components that have deteriorated. We watched Tim Hoffman, one of their craftsmen, build a 57-inch wheel for a Civil War cannon. It was a complex procedure. We learned pioneers used rawhide to repair their wheels.

Being a complete shop, besides carrying extensive wagon and buggy parts, they also supply horse harnesses for hitching and driving. This company has been a consultant and appraiser of horse drawn vehicles for many companies.

THEIR CLIENTS

They have done work for numerous museums, historical societies, theme parks, corporations, and individuals. You can see a list of these on their site under clients.

For Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village in Dearborn, Michigan, they constructed an authentic delivery wagon for daily use and restored large circus wagon wheels. They did restorations on several vehicles and repair and wheel work on others for Grant’s Farm-Anheuser Busch in Grantwood, Missouri. They have done lots of work for Wells Fargo Banks. They restored an Abbott Downing Concord Coach for display in their Minneapolis Museum. They also built a number of replica Concord coaches for Wells Fargo to use for display and in parades.

You can see some of their work on our web site. For the Great Platte River Archway, they constructed the Conestoga wagon, covered wagon, and Mormon Handcart that we show in our photos on November 29, 2018. They also supplied a lot of the period props. In our Deadwood article October 10, 2019, look for the ore mining wagon and stagecoach photos at Days of ‘76 Museum. This museum used Hansen Wheel and Wagon Shop to evaluate and restore 50 vehicles for their exhibits.

Their horse drawn vehicles have also been rented or purchased for movie productions. They can supply horse drawn vehicles, wood wagon wheels, and western props. They built a stagecoach for use in the movie Hateful Eight. For a film company in Germany, they provided a chuck wagon to use in their movie Gold about the Canadian frontier.

TOURS

Due to the corona virus, Hansen Wheel and Wagon Shop is not currently doing tours and they are rethinking whether to continue them. On past tours, visitors watched craftsmen at work including a wheelwright, blacksmith, and coach maker. It included a visit to the wagon barn of more than 30 historic horse drawn vehicles where the history of many was explained. The tours lasted an hour and took place Monday through Friday from 8:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. It cost $15 per person with a minimum of $60.

Readers can learn about the various types of horse drawn vehicles on this company’s web site. After frequently asked questions, you find fascinating information about all kinds of vehicles.

WHAT WE SAW

Since vehicles are constantly being restored or sold, it’s most likely that what we saw is no longer on their property. However, this will give you some idea of how varied they are.

We visited the main shop where we saw a bobsled sleigh being restored. Craftsmen take paint down by layers to get to the original paint. Since it was originally varnish over paint, they were going down to the varnish layer then replicating the original color and design. They have an upholstery shop and try to use the original wool fabric if their client wants it.

They were adding bows and canvas across the top of a Mitchell wagon besides adding a chuck box. This wagon was dated to the 1920's. They also added a seat as one was missing.

We then visited the upholstery shop. We saw a rare bobsleigh as it had four seats and was used for touring. It was going to a resort in Michigan.

On view was a Yellowstone coach for Cheyenne Frontier Days Museum in Cheyenne, Wyoming. On one side they had left the original paint, they redid the other side to match. Ardis Nelson, in charge of marketing for Hansen Wheel and Wagon Shop, advised us that they do a lot of work for this museum. Ardis added that they also do work for Donner Memorial Pass, the Smithsonian, and a lot of historical societies. Their forte is to be historically accurate.

We next saw a surrey where they were replicating the pattern of the original upholstery and making new leather seats. They have also redone the dash and fenders.

They had three vehicles in the field. These were an original Eastern style conestoga prairie wagon, a 1901 army escort wagon, and a surrey.

We met with Doug in the wagon barn where he discussed the types of vehicles we were seeing. We saw a yellow wagon which Doug said was a water or sprinkler wagon. It had a sprinkler on the back to control dust.

On the site was a streetcar used in the movie Meet Me in St. Louis. It was purchased at an auction and was being sold to a gentleman in Louisiana.

We saw a covered wagon that was 120 years old. The California stage wagon was part of Doug’s permanent collection and dated from the California gold rush. An 1870 light stagecoach had a unique design as it was lighter than most stagecoaches. A sleigh, delivery wagon, springboard, buckboard, three seater surrey, chuck wagon, and stagecoach could also be seen at the barn.

DETAILS

Hansen Wheel and Wagon Shop is located at 40979 245th Street, Letcher, South Dakota. Their telephone number is (605) 996-8754. Hours are Monday through Friday 8:00 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. After the corona virus is over, call them to see if they will be running tours.

Travelers to Mitchell find it offers more than the Corn Palace. The Dakota Discovery Museum combines art, history, and historic buildings. Mitchell Prehistoric Indian Village is an active archaeological site tracing a civilization from around 1,000 A.D. At Hansen Wheel and Wagon Shop, staff does sales, restorations, and custom work on all kinds of horse drawn carriages.

DAKOTA DISCOVERY MUSEUM

In 1939, Friends of the Middle Border founded a museum which later became the Dakota Discovery Museum. It has always been housed on the Dakota Wesleyan University campus.

On the second floor, you will find art galleries. The main level is dedicated to the Middle Border region (North Dakota, South Dakota, and parts of adjoining spaces) from the early days of the Dakota Territory to the 1930s. On the museum’s grounds, you can view four historic buildings.

Upstairs, you find three galleries. The Leland and Josephine Case Gallery features an original painting by Harvey Dunn entitled Dakota Woman. However, much of that space is used for changing exhibits. A second is devoted to numerous Oscar Howe paintings. Howe was recognized for revolutionizing Native American art.

A third is the Charles Hargens Gallery. He was known for his western illustrations capturing life in the West. Most of his illustrations were painted in oil on canvas although he also used pen and ink and tempera on paper.

The magazines for which he did illustrations include The Saturday Evening Post, Collier's, McClure's, Liberty, Gentleman's Quarterly, and Boys Life. He worked on book jackets, magazine illustrations, and advertisements for the Stetson Hat Company and Coca Cola and designed posters for ten years for the Multiple Sclerosis Society. In all, he illustrated more than 300 books and 3,000 magazines.

When he died in 1957, his family honored his wish that his Carversville art studio and many of his Western works be donated to the Dakota Discovery Museum. See these in this gallery today.

Downstairs, visitors explore, through a series of scenes, the traditions of the Plains Indians and early American settlers through life during the 1930s Great Depression. Note the extensive collection of Native American beadwork, an authentic tipi, and a conestoga wagon. Check out information on the Plains Indians as well as the fur trade. A claim shanty represents the Homestead Settlement Act. Commerce in the 1860s covers railroading and ranching. Another reveals the importance of agriculture to the state. The exhibit on the Great Depression of the 1930s includes a replica of Everett F. Cotton’s watch repair shop.

OUTSIDE THE MUSEUM

The historic village contains four buildings. It is reached by going out the front door and walking around the building. Due to lack of staff, guided tours of these buildings are at a minimum.

The 1886 Beckwith House was built by Louis and Mary Beckwith. He and L. O. Gale co-founded the Mitchell Corn Palace. The home was originally located in uptown Mitchell and is on the National Register of Historic Places. It was known as one of the town’s social places.

The home is of Italianate architecture with Queen Anne details such as a bay window, fish scale shingles, fretwork, and porch posts. Its original exterior colors of sage and dark sage with oxblood red accents are visible today. Many original furnishings remain in the home along with collections of the Beckwith clothing, memorabilia, and handmade needlework.

Built in 1884, the Sheldon County School was on land in another county. The property was donated by Millard Sheldon who constructed it. Patricia Geddes taught the first class in the spring of 1885. The school didn’t provide books so children brought their own from previous schools, borrowed them from parents or siblings, or shared books with other students.

The school also served as a community center with a lyceum conducted every two weeks during the winter. Community members provided recitations, music, and short plays. A debate on a current topic followed a short intermission. It closed in 1944-45 and was moved in 1965 to the museum grounds.

The Farwell Church congregation, organized in 1880, was assigned a regular preacher in 1883. The building, constructed during1908/1909, was originally located 16 miles northeast of Mitchell. It came to the museum in 1989. Its pews are original as is the basic building shape. Renovations have been made to the nave, ceilings, and dividing wall depending upon the congregation’s needs. It has been restored and is available for weddings and Sunday services with all denominations welcome.

When the Milwaukee Road built a railroad between Scotland Junction and Mitchell in 1886, Dimock was one of the stations. This depot dates to 1914 with Charles A. Johnson as agent. When he retired in 1963, the depot was then used on a part time basis by the agent from Parkston. In July 1971,the South Dakota Public Utilities Commission closed and removed the station. It was donated to the museum in 1973.

DETAILS

The address is 1300 McGovern Ave, Mitchell. The telephone number is (605) 996-2122. The museum is currently closed because of the corona virus. Normal hours are Monday through Friday from 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Admissions are seniors (63+) $6, adults $7, youth (ages 6-17) $3, and free under age six.

MITCHELL PREHISTORIC INDIAN VILLAGE

A LITTLE HISTORY

The Mitchell Prehistoric Indian Village is the only archaeological site in South Dakota open to the public. It is located on the bluff above Firesteel Creek near Mitchell. A Dakota Wesleyan University student discovered the site in 1910. W. H. Over, based at the University of South Dakota, mapped it for the first time in 1922.The bluff’s edges started to erode when the valley containing the creek was dammed in 1928 to create Lake Mitchell. During 1937 and 1938, a crew funded by the Works Progress Administration excavated two of the earth lodge depressions.

Dr. Robert Alex, from the University of Wisconsin, did the next professional archaeological work at the Mitchell site in 1970-71. He discovered a lodge whose evidence showed it was destroyed by fire but included remarkable architectural detail. In 1975, the Mitchell Prehistoric Indian Village Preservation Society formed to preserve the site.

In 1983, the Archaeology Lab at Augustana College in Sioux Falls, South Dakota assumed responsibility for the research and creation of an interpretative museum at the site. They were joined in 2003 by the Department of Archaeology at University of Exeter, Exeter, England. Now students from both schools come every summer for the site’s Summer Archaeology Field School.

The Village is special because it is one of the few sites in pristine condition in the Northern Plains that was never plowed or had any significant disturbance. It was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1964.

The public can visit the Boehnen Memorial Museum at the site and watch an active dig during the summer inside the Thomsen Center Archeodome. When funding allows, excavations take place year round. A laboratory and exhibits are also found in the Archeodome. In the museum, visitors discover a full-size reproduction of an earthen lodge, a bison skeleton, and cases of many artifacts found at the site. It’s the location for Shoppe Antiquary, which is the gift shop, and a video on the village.

WHY THIS SITE

Archaeologists believe these ancient people selected this site for a number of reasons. It was close to water which was necessary for drinking and cooking. During the dry times, they could water their crops. The creek also supplied fish and clams.

Since the site was on a bluff, it could serve as a defense against other tribes or against flooding. A palisade in the southwest portion of the village also helped protect it as did a ditch. Since lots of timber exists along riverbanks, the Indians had a good supply of wood to build and heat their homes, fire pottery, and use for such tools as spears and arrows.

WHO WERE THESE PEOPLE

They migrated to the Mitchell site from between 975 and 1100 AD from the eastern edge of what is now Minnesota/Iowa. Why they left is uncertain, but one plausible reason is that they ran out of natural resources, particularly timber. The evidence points to them eventually moving to North Dakota. The Mandans that Lewis and Clark discovered are likely descendants of these people.

They were farmers, gatherers, and hunters, particularly of bison but also of elk and deer. This was done on foot or by driving herds of bison over cliffs or into corrals. When animals were scarce, they survived on the food they grew. Various types of carbonized seeds and corn cobs show the villagers planted corn, soybeans, squash, beans, tobacco, and sunflowers. Corn was eaten fresh, dried, ground in wooden mortars, or leeched to produce hominy. The Amaranthus, a grain crop, was also grown.

They lived as extended families in rectangular shaped, earthen lodges resembling upside down baskets. These were 20 x 40 foot structures, not simultaneously built, housing 12 to 15 people. It is estimated 70 to 80 lodges are buried on the grounds that were homes to 500 to 800 people.

A mixture of mud, clay, or grass was plastered over the framework. Walls were about a foot thick. They had at least one fire ring or hearth for warmth and cooking though most of the cooking was done outdoors. The fire ring implies the presence of a smoke hole in the roof to keep smoke and toxic gases from building up in the home. Almost every lodge had an exterior storage pit large enough to accommodate the bushels of crops they grew.

They used tools similar to those of later tribes. These were made of bone, ceramic, shell, and stone materials. Many were used for farming such as bone hoes, sickles, squash knives, and deer antler rakes. Larger arrow points may have been used as knives, spears, or scrapers. Specially shaped ones could be used as drills, axes, or hammers.

Bone artifacts, mainly from bison, have been found in great numbers at the Mitchell site. Deer bones and those from smaller animals have also been discovered. These included long narrow and pointed awls. Awls were used for piercing holes for purposes such as sewing. Squash knives were made from a bison’s scapula. Utensils were fashioned from antlers and bones. Other bones were used for cutters, scrapers, and fishhooks.

To cook their foods, stones heated in the fire were dropped in round bottom pots containing water. Pots weren’t placed on the fire directly. Decorations were often drawn on the pot’s surface by using a pointed object, perhaps of wood or stone. Pottery, seeds, and foodstuffs were among the most actively traded items.

In 2015, on the site’s Archaeology Awareness Days, the excavation team found the first ever unbroken ceramic vessel. All pottery before that, since 1910, had been in pieces. Fortunately, archaeologists could form a complete impression from a pot’s fragment.

You can see a “bull-boat” at the Archeodome. They were constructed by stretching the hide of a bull bison over a wooden frame of branches. They hauled people and goods. Sometimes they were strung together to support large loads. Look for the dog and travois in the museum. Dogs were used to haul goods before the Spanish brought horses.

Weaponry improved because of trade. Early spears and lances gave way to spear-throwers and atlatls. Others consisted of bows and arrows and stone knives. Arrowheads, like pottery, reveal the influence of other cultures. Those at the Mitchell site had a variety of styles. They were made from various materials such as flints of different shades.

The site was once a major bison processing center. During the cold months, the bone grease was extracted from bison bones for the manufacture of pemmican. It was then mixed with dried meat pounded almost to a powder, dried grains, and dried chokeberries or other dried berries. It had a shelf life of at least eight years. It was an important trade item for the villagers as well as used for snacks and as a winter food.

Trade networks spread across the continent. Arrow points have been found from Canada, copper from the Great Lakes, and obsidian and lava from regions west of South Dakota. Local mollusk shells and decorative seashells from the Gulf of Mexico have been excavated on the Mitchell site. This indicates they traded with tribes from those areas. Shells were used for decorating clothing or as jewelry. Making beads was common in late Stone Age sites. The Mitchell people produced tubular and flat disc shell beads.

Archaeologists are now employing new tools besides trowels, picks, and brushes. Among these are computers and electron microscopes. Electric resistance, magnetism, and radar are currently used to explore buried sites without digging. It is hoped that radiocarbon dating, soil and mineral analysis, and newer ways to use DNA will increase the knowledge of these scientists.

What won’t be discovered at the site are wood and other vegetable materials. For example, archaeologists find arrow points but no arrows. Post holes exist but no poles. Fibers and skins are also erased by time leaving little evidence of what those at the Mitchell site wore. Only the most durable materials remain - stone, baked clay, and bone.

VISITING THE SITE

In the summer, take a guided tour of the museum and the Archeodome by knowledgeable guides. Look for the chart explaining how each part of the bison was used by those who lived at the site. Visitors also see a diorama of the village and can explore a reconstructed lodge.

The museum’s cases contain lots of items excavated at the Archeodome. These include needles, awls, buttons, arrowheads, and fish hooks. Ask your guide about the Atlatl, the throwing spear. We were fortunate enough to have our guide, Dennis Scott, demonstrate it for us.

On the way to the Archeodome , Dennis pointed out the Flame of Wisdom statue by Leonard Nierman in 1999. Made of stainless steel, it was presented on this building’s dedication.

Audry’s Garden is the newest exhibit. It showcases the native plants that the villagers used for foods, medicines, dyes, and ceremonies, It consists of 36 different species. Flowering occurs from late March through late fall. Information plaques identify each plant and its uses.

The Archeodome, erected in 1999, is one of a handful of enclosed archaeological teaching and research facilities in the country. The exposed earthen floor is where the dig occurs. Exploration occurs where no lodges are known to exist. As of 2018, archaeologists were exploring caches at the four or five-foot level. A wealth of artifacts is expected to be located 10 to 12 feet below today’s ground level. At this rate, according to Dennis, the excavation will take about 50 years. So far, archaeologists have discovered 1.5 million artifacts on the site during the 20 years of excavation.

All findings are placed into pails in ziploc containers to be taken to the laboratory and processed. All bags are numbered. Particular attention is paid to the artifact’s location which is mapped on a grid. Important information about the past may be revealed in minor changes or soil color and texture. For example, areas of light clay may indicate evidence of burrowing animals. Ash concentrations represent materials cleaned out of fire hearths.

At the Archeodome, visitors find cases of artifacts. One includes a bone fish hook, a knife handle, and a projectile point. Another consists of bone tools while a third has chipped stones used as scrapers, drills, projectile points, and knives. Three contain maize. Nearby is a video of the 2017 excavation. Mississippian pottery such as a reconstructed pot and ceramic discs are also on view.

Children enjoy the “Kids Dig” in the Archeodome. They learn how archaeologists sort bone, stone, and ceramic artifacts. They can excavate plastic arrowheads and turn them into the gift shop for a real arrowhead.

SPECIAL EVENTS

In mid-June, the students from Exeter University arrive. You can watch their excavations. Archaeology Days are scheduled for June 27 and 28 in 2020. It’s the site’s biggest event of the year showcasing archaeology awareness, primitive technology, and Native American culture. The second annual Native American Lore and Culture Day will be held July 25, 2020. Visitors learn how to make corn husk dolls, play ancient Lakota games, make pottery, listen to storytellers, and more.

DETAILS:

The Mitchell Prehistoric Indian Village is located at 3200 Indian Village Road in Mitchell. The telephone number is (605) 996-5473. They are closed now because of the virus. They are usually open Monday through Saturday from April to May and September to November 15 from 9:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. with the last tour at 5:30. From Memorial Day to Labor Day, their normal schedule is Monday through Saturday 8:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m. and Sunday 10:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. Admissions are adults $6, seniors (60 up) $5, students (13-18) $4. For ages 12 and under, it’s free.

HANSEN WHEEL AND WAGON SHOP

WHAT DOES THIS COMPANY DO

Have you ever wondered where a lot of horse drawn vehicles you see in museums and living history farms come from? The premier custom builder, restorer, and seller of these vehicles is Hansen Wheel and Wagon Shop. They have worked with stagecoaches, chuck wagons, hitch wagons, freight wagons, and many more. It’s a company motivated by a love of history and a desire to preserve our heritage. The company is rurally located just off SD Highway 37 between Mitchell and Letcher, South Dakota.

Doug Hansen and his wife Holly started the company in 1978. Doug’s mother was a horsewoman who wanted her son to make a hitch for her buggy. She then asked Doug to restore the buggy. He did research at local firms and borrowed tools from them to accomplish this task. He also learned to repair wheels. People from the area starting bringing him their buggies and a business started.

The staff of 12 consists of skilled craftsmen who pay meticulous attention to details. They come with skills then are trained into a special skill: wheelwright, wainwright (wagon builder), painter, or upholsterer. One gentleman does restoration.

“It matters to us to do it right,” said Doug. “That’s what we built our reputation on. But it’s also a responsibility for the craft that we’re representing because if we do it wrong, we’re polluting. It’s not how we do it but how they did it, and that’s what we need to replicate.”

For custom vehicles, their goal is to maintain the durability and style of the original design. At the same time, they incorporate the client’s wishes for design elements.

Restoration starts with careful research and documentation about the original vehicles and makers. For example, the original color, striping, and trim on these vehicles indicate the manufacturer and the era that they were built. These can be sometimes hard to identify because of the erosion of design details.

Hansen Wheel and Wagon Shop craftsmen use authentic materials and construction, adding finishes that define the original maker’s art. They restore the vehicle to look as original as possible. Historic horse-drawn vehicles were once stripped of their original paint, decoration, and trim during the restoration process. It’s now recognized that it’s important to preserve what remains in order to keep the vehicle’s value.

During restoration, craftsmen find blacksmith marks, a serial number, and occasionally a date. At other times, the date is unknown. One manufacturer, Peter Schuttler, stamped a date on his wagons. However, on the Schuttlers, it is unknown if the date applied to when the wagons went into the drying shed or rolled off the assembly line. The earliest Schuttler that Doug worked on was an 1883 freight wagon used at Lead’s Homestake Mine. It was for a museum at Deadwood.

The shop also carries an inventory of more than 40 horse drawn vehicles manufactured between 1850 and 1911. In August of 2018, we visited the wagon barn where a quarter of the vehicles was Hansen’s private collection. Of the remaining ones there, half were in for restoration and half in the inventory for sale.

In addition, to the above, they do axle repair and build and replace wagon wheel components that have deteriorated. We watched Tim Hoffman, one of their craftsmen, build a 57-inch wheel for a Civil War cannon. It was a complex procedure. We learned pioneers used rawhide to repair their wheels.

Being a complete shop, besides carrying extensive wagon and buggy parts, they also supply horse harnesses for hitching and driving. This company has been a consultant and appraiser of horse drawn vehicles for many companies.

THEIR CLIENTS

They have done work for numerous museums, historical societies, theme parks, corporations, and individuals. You can see a list of these on their site under clients.

For Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village in Dearborn, Michigan, they constructed an authentic delivery wagon for daily use and restored large circus wagon wheels. They did restorations on several vehicles and repair and wheel work on others for Grant’s Farm-Anheuser Busch in Grantwood, Missouri. They have done lots of work for Wells Fargo Banks. They restored an Abbott Downing Concord Coach for display in their Minneapolis Museum. They also built a number of replica Concord coaches for Wells Fargo to use for display and in parades.

You can see some of their work on our web site. For the Great Platte River Archway, they constructed the Conestoga wagon, covered wagon, and Mormon Handcart that we show in our photos on November 29, 2018. They also supplied a lot of the period props. In our Deadwood article October 10, 2019, look for the ore mining wagon and stagecoach photos at Days of ‘76 Museum. This museum used Hansen Wheel and Wagon Shop to evaluate and restore 50 vehicles for their exhibits.

Their horse drawn vehicles have also been rented or purchased for movie productions. They can supply horse drawn vehicles, wood wagon wheels, and western props. They built a stagecoach for use in the movie Hateful Eight. For a film company in Germany, they provided a chuck wagon to use in their movie Gold about the Canadian frontier.

TOURS

Due to the corona virus, Hansen Wheel and Wagon Shop is not currently doing tours and they are rethinking whether to continue them. On past tours, visitors watched craftsmen at work including a wheelwright, blacksmith, and coach maker. It included a visit to the wagon barn of more than 30 historic horse drawn vehicles where the history of many was explained. The tours lasted an hour and took place Monday through Friday from 8:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. It cost $15 per person with a minimum of $60.

Readers can learn about the various types of horse drawn vehicles on this company’s web site. After frequently asked questions, you find fascinating information about all kinds of vehicles.

WHAT WE SAW

Since vehicles are constantly being restored or sold, it’s most likely that what we saw is no longer on their property. However, this will give you some idea of how varied they are.

We visited the main shop where we saw a bobsled sleigh being restored. Craftsmen take paint down by layers to get to the original paint. Since it was originally varnish over paint, they were going down to the varnish layer then replicating the original color and design. They have an upholstery shop and try to use the original wool fabric if their client wants it.

They were adding bows and canvas across the top of a Mitchell wagon besides adding a chuck box. This wagon was dated to the 1920's. They also added a seat as one was missing.

We then visited the upholstery shop. We saw a rare bobsleigh as it had four seats and was used for touring. It was going to a resort in Michigan.

On view was a Yellowstone coach for Cheyenne Frontier Days Museum in Cheyenne, Wyoming. On one side they had left the original paint, they redid the other side to match. Ardis Nelson, in charge of marketing for Hansen Wheel and Wagon Shop, advised us that they do a lot of work for this museum. Ardis added that they also do work for Donner Memorial Pass, the Smithsonian, and a lot of historical societies. Their forte is to be historically accurate.

We next saw a surrey where they were replicating the pattern of the original upholstery and making new leather seats. They have also redone the dash and fenders.

They had three vehicles in the field. These were an original Eastern style conestoga prairie wagon, a 1901 army escort wagon, and a surrey.

We met with Doug in the wagon barn where he discussed the types of vehicles we were seeing. We saw a yellow wagon which Doug said was a water or sprinkler wagon. It had a sprinkler on the back to control dust.

On the site was a streetcar used in the movie Meet Me in St. Louis. It was purchased at an auction and was being sold to a gentleman in Louisiana.

We saw a covered wagon that was 120 years old. The California stage wagon was part of Doug’s permanent collection and dated from the California gold rush. An 1870 light stagecoach had a unique design as it was lighter than most stagecoaches. A sleigh, delivery wagon, springboard, buckboard, three seater surrey, chuck wagon, and stagecoach could also be seen at the barn.

DETAILS

Hansen Wheel and Wagon Shop is located at 40979 245th Street, Letcher, South Dakota. Their telephone number is (605) 996-8754. Hours are Monday through Friday 8:00 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. After the corona virus is over, call them to see if they will be running tours.

Dakota Discovery Museum

Charles Hargens

The Studio of Charles Hargens

Untitled by Charles Hargens

A Saturday Evening Post Cover by Charles Hargens

Sioux Riders by Oscar Howe

Boehnen Memorial Museum and Visitors Center

One of the Scenes at the Museum - Bison Roaming the Area

How the Village's Lodges Might Have Been Laid Out

Full Size Reproduction of An Earthen Lodge

Reproduction of the Interior of a Lodge

Flame of Wisdom Statue by Leonard Nierman

Thomsen Center Archeodome Where the Excavations are Taking Place

Overview of Excavation Site

Close Up of Excavation

Showing Artifacts at Dig

Bull Boat the Villagers Would Have Used for Transportation

Bone Artifacts That Have been Excavated

Chipped Stone Artifacts Found at the Site

Fragments of Mississippian Pottery

This Building Houses Hansen Wheel and Wagon Shop's Offices and Major Shop

Tim Hoffman Creating a 57" Wheel for a Cannon

Upholstery Shop

Ardis Nelson, in Charge of Marketing, Shows the Upholstery Tools

Rare Four Seater Bobsleigh That Was Being Restored in the Upholstery Shop

Surrey They Were Restoring

Making A New Seat for the Surrey

Wagon Barn

Closer View of Some of Their Wheels

Trolley That Was in the Movie Meet Me in St. Louis

Some of the Wagons in the Wagon Barn

Doug Hansen Pointing Out One of His Wagons

Conestoga Freight Wagon Out in the Field