Hello Everyone,

South of Canton, in the town of Dover, one museum has attracted visitors for decades, The Warther Museum. It’s Mooney Warther’s 64 impeccable carvings which trace the history of steam locomotives that’s the main draw. They start in 250 B.C. with Hero’s Engine and end with the Union Pacific Big Boy Locomotive of 1941. All are hand carved to scale with many moving parts. They were accomplished between 1905 and 1971 when he was between the ages of 20 and 86.

A tour of the house, a building full of incredible button designs, Swiss gardens, and a peek into the Warthers lives contribute to making this a not to be missed wonder in Northeast Ohio. To call it an attraction, fails to give it the dignity that Warthers deserves.

The Smithsonian Institute has appraised Warther’s carvings as priceless. They found his contrast of color, sense of proportion, and attention to detail is what makes the collection a true work of art. They also called it a one of a kind.

In 2016, the local newspaper, The Times Reporter, ran a Reader’s Choice Contest. The museum took third place for Best of the Best People and Places. It has been called a AAA Gem attraction and a 5 Star TripAdviser attraction.

ERNEST “MOONEY” WARTHER

Ernest “Mooney” Warther was born October 30, 1885 in a one-room schoolhouse in Dover, Ohio. He used to tell people that was why he didn’t need much formal education. When he was three, his father died, leaving his mother with five children, twenty cents, and a cow. From age five through fourteen, he herded cows for a penny apiece for area families. That is why he received his nickname “Mooney” from the Swiss word “Moonay” meaning “Bull of the herd.”

At the age of five, while taking the cows out to the pasture, he discovered a rusty jackknife in the field. He took it home and started whittling. When Mooney turned ten, a hobo gave him a block of wood with ten cuts that made a working set of pliers. Mooney sat down and figured out how to make one for himself. By the time he was in his twenties, he could carve a working pliers in under twenty seconds. They became his calling card. He gave one to every child who visited his shop or museum. Pliers are still cut by family members and are available for sale.

In the museum’s theater, you’ll see the walnut plier tree he made in 1913 at age 28. Considered to be his “Grand Finale” of whittling, the sculpture consists of 511 interconnected pliers out of one block of wood. Mooney carved it over 64 days, one hour a day, placing 31,000 cuts into the wood. No shaving was ever removed from it nor are there pins or glue holding it together,

The tree has only been retracted into its closed position once. This was done for Robert Ripley at the 1933 Chicago’s World Fair. The piece was so unique that Ripley of Ripley’s Believe it or Not wanted it for his museum. It has been featured in McGraw-Hill algebra book as an example of perfect geometric progression. You can see it at the museum today. On the wall, visitors view a triple set of pliers with 32 cuts and seven pliers formed from 82 cuts.

Having only a second grade education and no formal art or carving lessons, Warther concentrated on teaching himself. He read every book that he could find and could quote Bible verses. “He would read encyclopedias until they were worn out,” said Jean Nadeau, our guide.

As a teenager, his love for the railroad and steam engines became his focus for carving. He quickly ceased being a stranger to the railroad yards and maintained an extensive library of repair manuals from the roundhouses. These proved invaluable in crafting his intricate models.

He believed steam engines had advanced civilization more than any other invention and were never used for warfare. He also wanted to carve something mechanical and felt strongly that the steam engine satisfied that desire.

He was fourteen when he lied about his age and started working as a scrap bundler at American Sheet and Tin Plate Company, the local steel mill where he worked for 24 years. He eventually worked his way up to head shearsman. The mill, located a mile south of the museum, stopped operating in 1931.

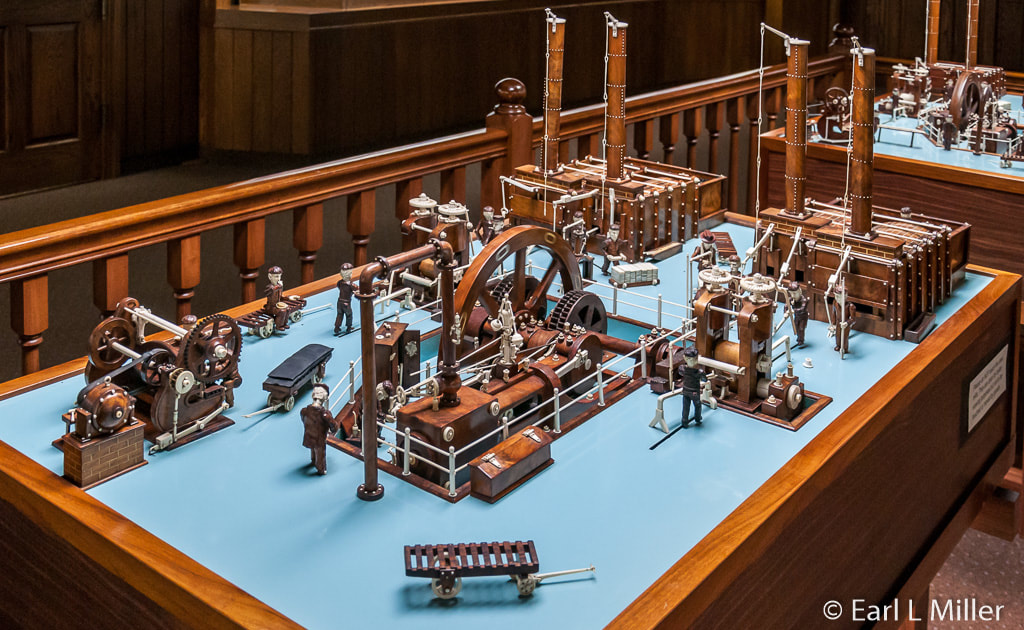

You can see his animated model of this mill complete with 17 figures in the museum’s Early Years Room. It includes a figure of a man eating rhubarb pie and Swiss cheese at lunch because the man always did. Motion is conducted via leather sewing machine belts and a series of pulleys. It was one of five models that he made of this scene. He carved this one in 1952.

Through his reading, he learned ebony and ivory were found inside Egyptian tombs. Wanting his train carvings to permanently last, he used these same materials. Mooney’s motto was “Build everything to last forever.”

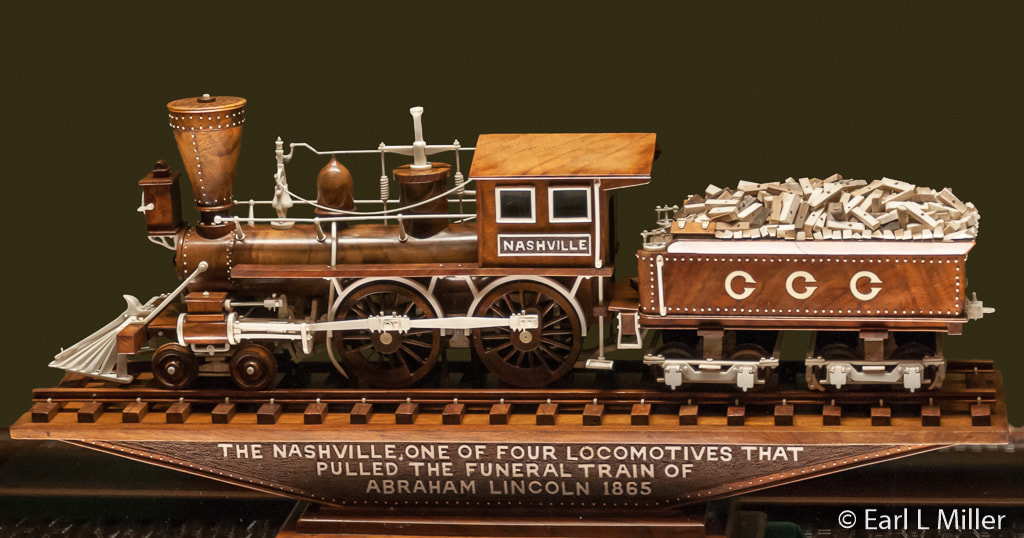

He made his earliest carvings from walnut wood using beef soup bones for white trim. On 14 of these, he later recarved the bone pieces out of ivory. In 1923, he started to purchase ivory. He obtained that material first from chipped billiard balls and then from the tusks of elephants who had died naturally. He used hippopotamus ivory (the finest type available), only once - when he carved Lincoln’s Funeral Train.

Mooney used his wife’s broaches and gemstones for smaller details such as lantern lights. For a lot of the trim work, he used mother of pearl and abalone shell. He used Arguto Oilless Bearing Company wood which is naturally oil-impregnated. It solved the problem of lubricating the moving pieces so his carvings would never need oil.

When Warther carved the history of steam locomotives, all parts were created using hand saws, files, eggbeater drills, and his handmade knives. It was not until his mid 70's, when the density of ebony and walnut became a problem for him, that he used his first power tool, a Delta Milwaukee drill press. He pressed the parts together or used pins but never glue since the old glues weren’t permanent. Everything was made to the scale of one-half inch equals one foot. All was done by free hand without a lathe.

Mooney set a goal based on the number of pieces and knowing how much time it would take him to carve that many pieces. There were very few carvings where he missed his goals. He kept drawings, notes, and plans in his personal journals, documenting his days and the progression of his collection. One carving was done at a time.

Viewing the carvings, you’ll quickly discover that he was a mathematical and mechanical genius. His locomotive models are to scale, inside and out, for locomotives and box cars. Such elements as cab interiors and mechanical movements are accurate. All models feature working pistons, flyrods, and wheels powered from underneath by a small electric motor and a sewing machine belt. There are many non motorized moving parts as well. Bells swing. Couplers open and close. The valves on the piping are pinned. Nuts, bolts, and rivets are in ivory. It is said that no engineer ever found any part missing in any way, shape, or form.

At the age of 25, on October 29, 1910, he married Frieda. They had five children. Today many third and fourth generation Warthers are carvers or active with the museum. Among those are granddaughter Carol, who runs the business, and David, a grandson, who has his own museum where he has traced the history of sailing ships.

By the 1920's, Warther carved constantly and was developing a reputation. In 1923, the Cleveland Plain Dealer ran a story about Warther and 15 models he had made. Alfred Smith, president of the New York Central Railroad, was so intrigued that he sent representatives to Dover to meet Warther. Mooney went with them to New York to promote their “Service Progress Special” railroad tour. When people came on board to see his carvings, he would explain why they needed to take the train. He traveled the rails with his collection for six months. Then he lived in New York City for 2-1/2 years while the collection was shown at Grand Central Station. After doing this to get money for his ivory, Warther returned home in 1926.

The railroad offered him $50,000 for his collection and $5,000 a year to live in New York. Henry Ford also proposed to pay him a handsome sum. However, Warther turned these offers down since he never wanted to sell any of his pieces. He did give 17 carvings away. All were returned except for two, and the family knows where they are.

After working for the railroad, Mooney’s brother Fred put the models in the back of a used truck he designed. The special truck had shelving and was on a Graham chassis. Charging ten cents admission to the exhibit, he drove this traveling train museum for 30 years throughout all of the states from 1927 to 1957.

Mooney did not always go on the road with his brother. He remained home carving and making knives for a living.

He had not been satisfied with store-bought knives when he began his carving. They didn’t conform to his hand or hold their edge well when carving such materials as ebony, ivory, and walnut. To satisfy his needs, he designed his own carving knives with 139 interchangeable blades, each with a different cutting profile. Blades were about an inch long, locked into place, and kept in the handle. These are on display at the museum.

In 1902, finding that Mooney’s knives held their sharpness, his mother asked him to make her a paring knife. Mooney made her one for Mothers’ Day. Neighbors soon ordered them. By 1923, he quit his job in the mill and devoted his time to his hobby of carving and to making kitchen knives.

To support his carvings, Warther started the Warther Kitchen Cutlery business which exists at the museum today. His three inch “Old Faithful” paring knife, that he first made in 1905, is a best seller today. The trademark of a swirl on the blade has also continued.

During World War II, he designed 1,100 knives for soldiers. A neighbor asked Mooney to make a knife to protect her husband. Today, during May and September only, you can see a collection of these knives. Twelve are shown with different size blades. Some handles of leather were made on request by specific individuals.

At age 68, he finished making steam engines and refused to carve diesels. He stopped working for four years before turning to historical events such as the carving of the Golden Spike and Lincoln’s funeral train.

On June 8, 1973, Mooney Warther died at the age of 87 due to a stroke. He was working on the Lady Baltimore & Ohio. This unfinished piece can be seen at the museum today.

LOBBY AND SHOP AT THE MUSEUM

The Warthers Museum opened in May 1936. Its first addition was in June 1988 with a building expansion in 2002. Tours last from slightly over an hour to 1-1/2 hours and are held upon request rather than on a regular schedule.

While waiting for the tour, observe the lobby exhibits. You will see a portrait of Mooney carving Abraham Lincoln’s funeral train during 1964-65 as well as photos of him giving pliers to General Omar Bradley and his 1954 meeting with President Nixon. You will also see a bust of Mooney by Walter Senz done in Cleveland in 1963. It was awarded to Warther at Crater Stadium in Dover.

Upon entering the museum, you can peek through the door at Mooney’s 1912 shop. It was in this shop that Mooney built a fireplace so he could temper steel and make knives. The fireplace did not have a bellows. Mooney depended upon its updraft.

On the walls and ceiling, you will find a collection of 5,000 arrowheads and points placed into numerous designs. Eighty-five percent of these are local. Mooney bought, traded, and bartered for them. He also would take weekly walks with his wife, Frieda, and their children through valleys and fields to collect them. Frieda would place these arrowheads into designs which visitors see today.

The shop also contains lots of reference books and a drawer full of various types of sandpaper ranging from coarse to fine. Plenty of tools are placed around the shop as well. He made his own tools with handles to fit his hand so he could work for longer periods of time.

Warther carved 64 steam locomotives at the rate of 1,000 pieces for them a month. It was not uncommon for him to work in the shop for 12 hours a day, six days a week starting at 2:00 or 3:00 a.m. He spent half of the time on carving and half on making knives.

THE EARLY YEARS ROOM

Besides Warther’s animated mill, this room houses some of his early works. Take time to watch the short video in the theater about Mooney’s life.

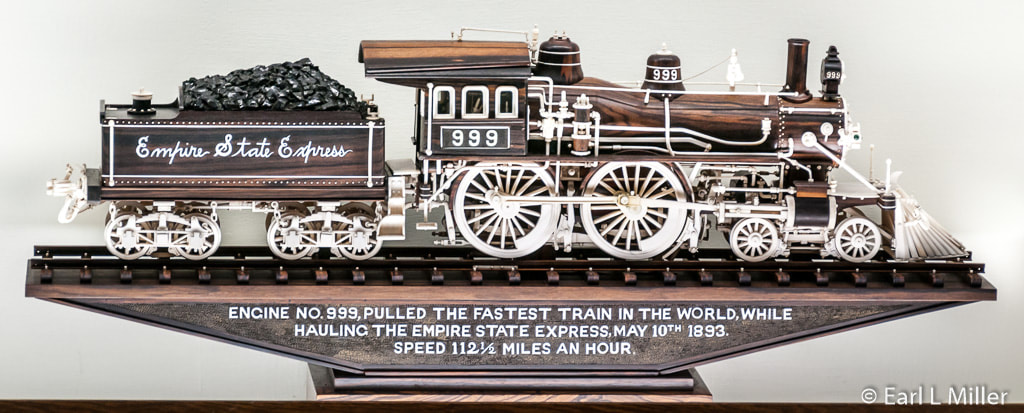

On display, is Mooney’s favorite, the Empire State locomotive #999, which he carved five times out of different materials. The eight- foot model took Mooney one year and four days to carve. Its sits on blocks made of ebony with ivory mortar. He gave his son David one of these as a newlywed present. David picked the pieces apart to show how extensive the model was.

The actual locomotive was the fastest one in the world at one time. While hauling the Empire State Express on May 10, 1893, it reached a speed of 112-1/2 miles per hour.

HISTORY ROOM

In this room, you will discover several extensive carvings and can watch a 10 minute video about Warther. These are ones he worked on when he was tracing the evolution of steam from 250 B.C. up to the 1900's. Carvings grew in size from several hundred to several thousand pieces as his work became more intricate.

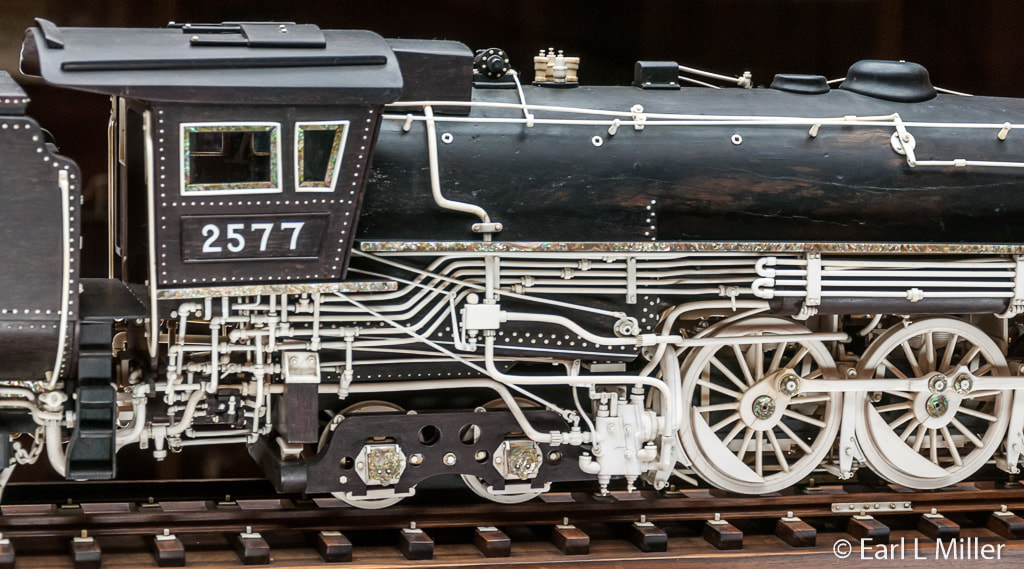

Mooney considered his masterpiece the Great Northern Mountain Type 4-8-4 locomotive which he carved between September 1932 and May 1933. It consisted of 7,752 parts. He used abalone pearl in the wheel covers and on the logo in the cab’s side. The handwriting on the ivory base inlay was his. A lot of its pieces move and the volume of fittings in it is incredible. The actual train was designed and built by the Baldwin Locomotive Works.

The first of his models to use ebony was the New York Central Lines 4-6-4 Hudson type locomotive. The American Locomotive Company designed the engine in 1927 to haul trains providing Limited service. Carved in eight months, it had 7,332 pieces. Warther also created the bases and rails for his pieces.

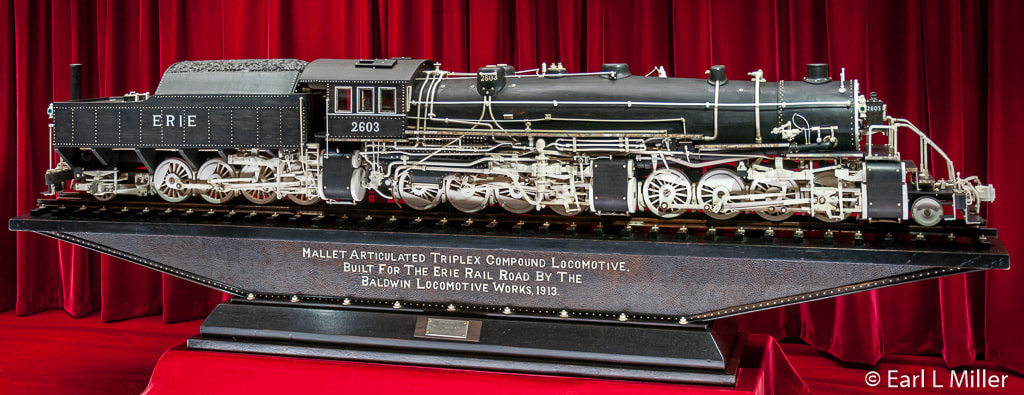

The Mallet Articulated Triplex Compound locomotive consisted of 1,504 pieces. It took him 9-1/2 months to carve and was completed in 1931. The engine was built for the Erie Railroad by the Baldwin Locomotive Works in 1913.

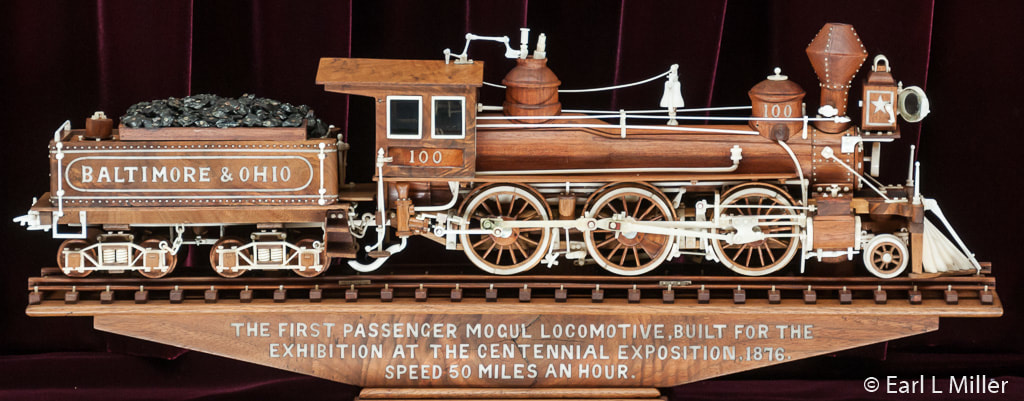

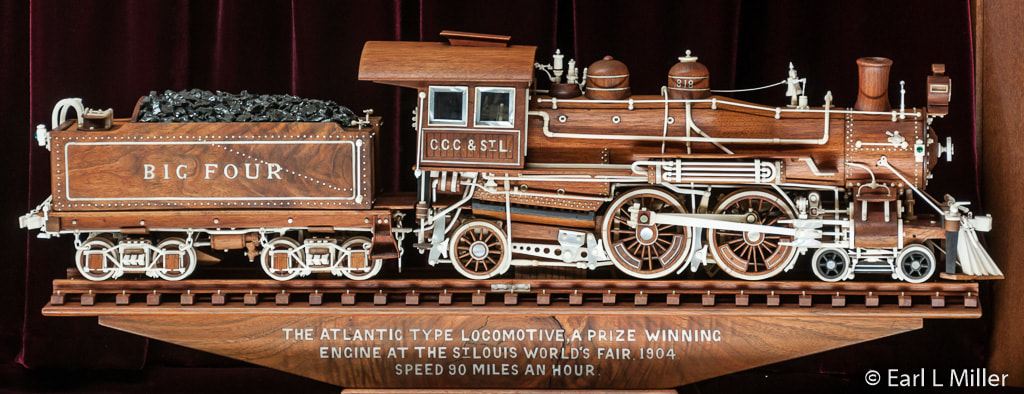

The first passenger Mogul locomotive was built for the 1876 Centennial Exposition. It traveled at 50 mph. The Atlantic Type Locomotive A was a prize winning engine at the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904. Its speed was 90 mph.

Another carving was of the 1941 Union Pacific Big Boy built by American Locomotive Works. Completed on Mooney’s 68th birthday. When he finished this one, he announced he had completed carving the evolution of steam. Currently, the city of Cheyenne, Wyoming is rebuilding an American locomotive. It will weigh 604 tons.

Warther did many smaller historic models, too, that can be seen in this room. Among the earliest associated with steam engines are Hero’s engine from 250 B.C. in Alexandria, Egypt and Whirling Aeolipile from Greece’s first century A.D.

Others include Leonardo Da Vinci’s steam engine from Milan, Italy in the late 15th century, Branca’s steam turbine from Rome in 1629, and James Watts condensing engine from London in 1774. On display is a model of Sir Isaac Newton’s proposed locomotive in 1680 and Newcomen’s Atmospheric engine from England in 1705. He also carved Trevithick’s locomotive which was built in South Wales and was the first engine to run on rails in 1803. It had a speed of 5 miles per hour.

Others are DeWitt Clinton’s first locomotive of the New York Central Railroad dated 1831 and Old Ironsides, a model of Baldwin’s first locomotive in 1832. The carving of James Milholland’s Illinois locomotive, from 1852, the first passenger engine to burn anthracite coal, is also found. The Atlantic type locomotive was a prize winning engine at the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904. It had a speed of 90 miles per hour.

Mooney also carved three elephants. One is on display as is the cane he carved for Lindbergh. He also made walking canes and other gifts for Roosevelt, Omar Bradley,our last five star general Eisenhower, and Nixon.

IVORY ROOM

Ivory models are housed here. This includes his “Great Events in American Railroad History” done between the ages of 72 and 85. Among these are the Great Locomotive Chase of the Civil War, the Casey Jones locomotive, and the first passenger train, the John Bull.

It is also the home of his unfinished Lady Baltimore on which he was working when he died. The B&O was the first passenger train. It was exhibited at the 1876 Centennial Exposition and had a speed of 50 miles per hour.

Perhaps, the most famous one is Warther’s Lincoln’s funeral train. Mooney chose Lincoln as a father figure. Perhaps, that was because he lost his own father at so young an age. He liked Lincoln’s philosophy and read every book on his hero.

Taking one year to carve, everything about the Lincoln funeral train is historically correct. Mooney finished it on the 100th anniversary of the assassination in 1885. He has Lincoln lying in a coffin. The presidential seal has scrimshaw engraved in the ivory oval. There are mother of pearl accents at the bottom of each car.

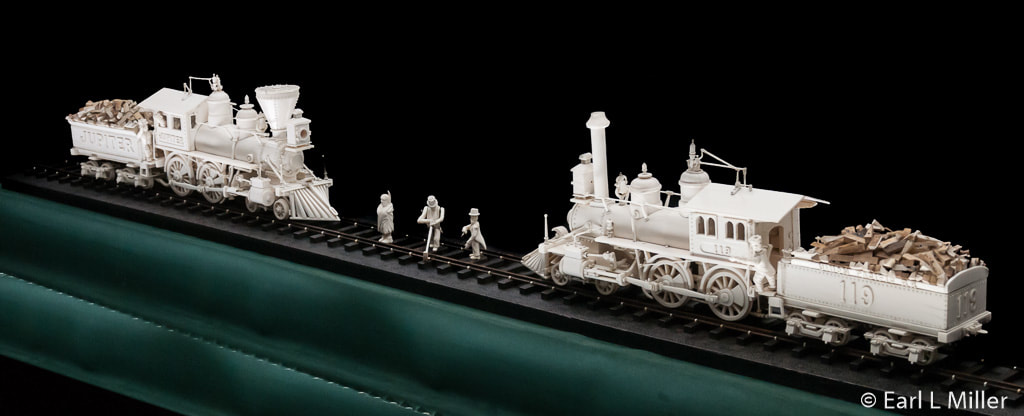

Mooney also carved the Golden Spike event though it is not historically accurate. He had President Grant smoking a cigar though Grant was never there. Mooney commented, “He should have been there.”

He also has a Native American in the scene. None were present. Mooney stated that in respect for the Native Americans he placed an Indian there since it was their territory. His spike is gold, which he received from a dentist, Dr. O. K. Brown.

One model he did, the #999, was eight feet long and weighed 81 pounds. It was made up of 11,000 pieces with 4,000 of those making up the bridge on which it sat. He did it at the age of 76. It took him a year and four days.

WARTHER HOME

Outside the museum, you will find a burnt brick home moved into by the Warthers in 1912. Their oldest daughter, Florence, lived there until 2005. The home has been restored to the 1920's. Visitors only see the downstairs portion of the kitchen, dining room, library, and parlor since the three bedrooms upstairs aren’t on the tour. Most of the pieces belonged to the family. Almost all woodwork is original.

The parlor is typical early 1900s with a radio receiver, spinning wheel, doll carriage, and Victrola. They never had a television as Mooney felt it was too time consuming. The stove and sink dominate the kitchen. A table glides open to widen and become different sizes.

Mooney soon discovered that it was too cold to work in the shop he had built. He moved his tools inside and set up his carving in the library. He had his models all over the house. In 1951, he built the brick building known as the button house and took his carvings there.

BUTTON HOUSE

Frieda Warther was born in Switzerland in 1890. The family moved to Dover when she was four years old. Being the oldest girl of 13 children, she earned the gift of her mother’s button box, a European tradition that gave the eldest daughter a box full of buttons and sewing tools. She collected many buttons from girls who gave away their mothers’ boxes.

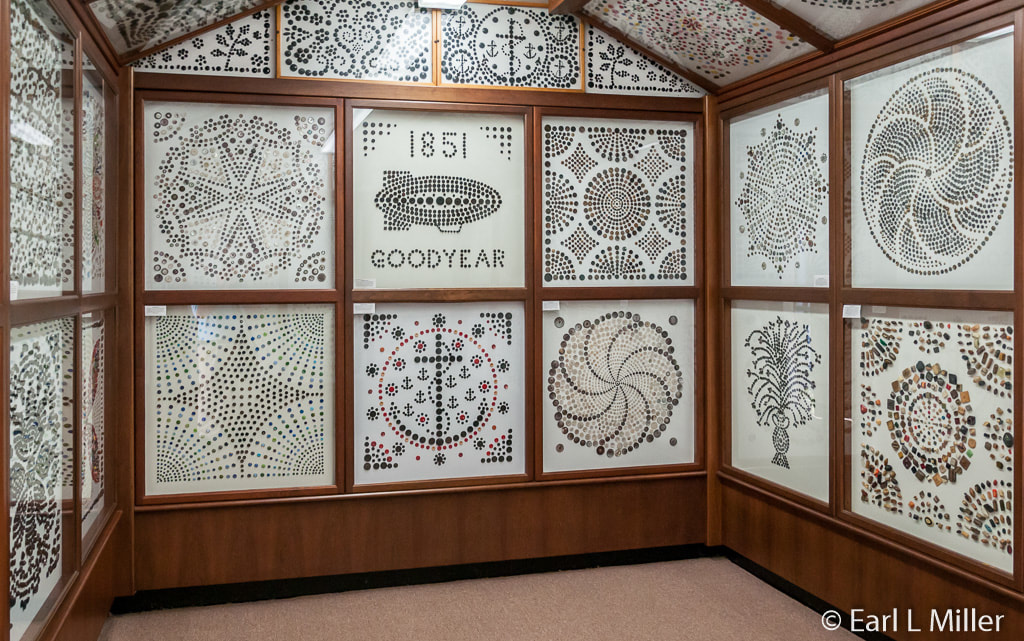

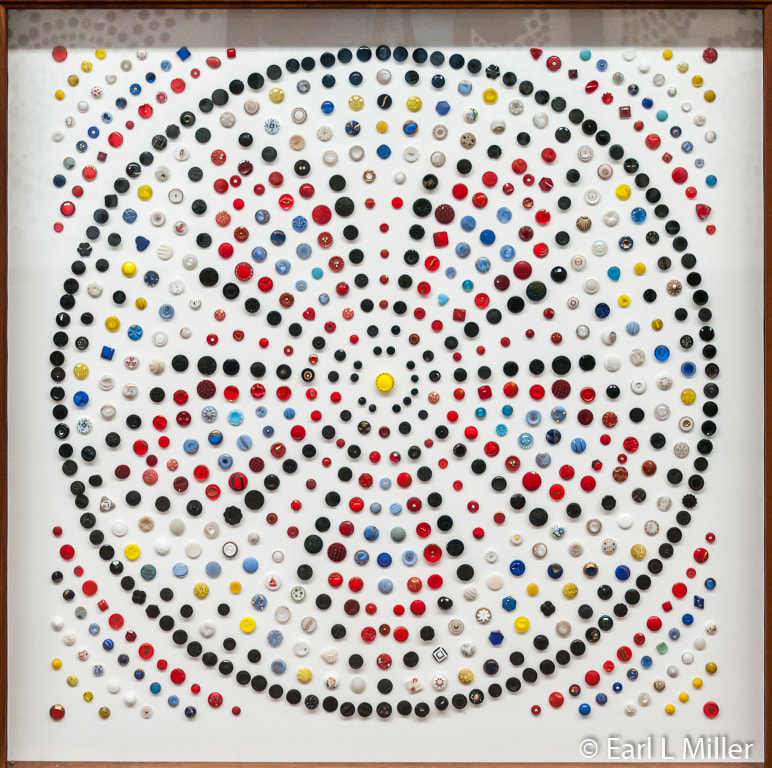

In addition to creating designs with arrowheads, Frieda collected over 130,000 buttons between the ages of nine and 90. You’ll find 73,000 are mounted at the museum’s button house. Before being placed into designs, these were separated by size, color, and style.

By the 1950's, when the children had grown up, Frieda set up the dining room to make her button designs. She used paper drawings and a homemade compass to design her layouts, Then she would take squares of Marlite, drill holes, and attach her button design on the Marlite using dental floss, carpet thread, and some glue. Visitors see holes in the dining room table today where she drilled too deeply.

Her 47 designs can be seen covering all four walls of the Button House. They’re composed of buttons of various types. In 1992, David, the Warther's youngest son, redid these. They’re now attached by colored wires to Corian counter top material

The buttons are of various types. The calico buttons are made to look like cloth and come in hundreds of designs. Celluloid buttons were created from the late 1800's to the 1920's. They are a composite of plastic and plant-based resin. Her cameo buttons represent such women as Egyptian queens, Lady Liberty, and Queen Elizabeth the Second.

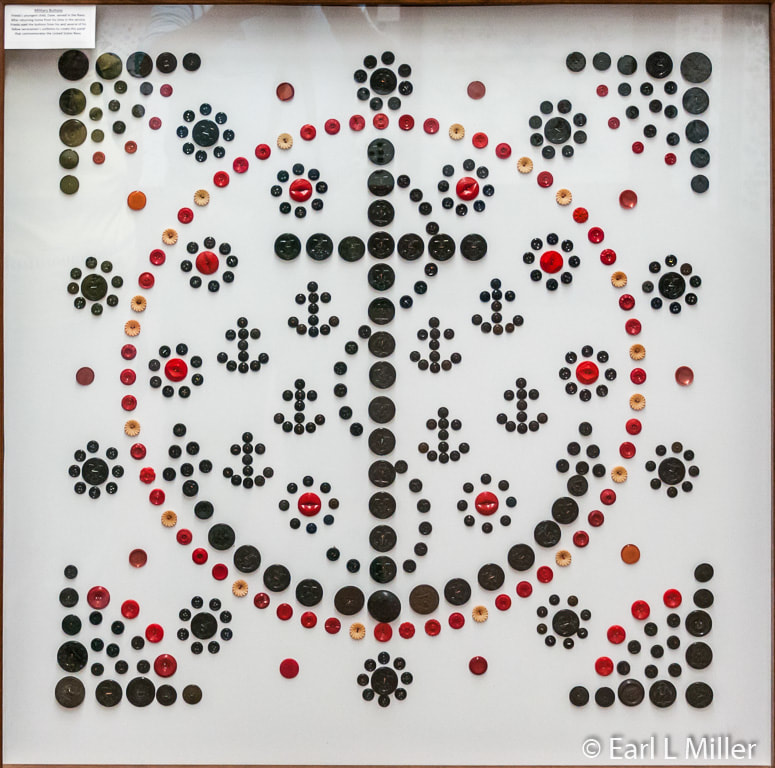

Brass buttons had to go through a process so they would not tarnish and deteriorate. Horse bridle buttons came from horse bridles. One design is made of Goodyear rubber buttons. Before Goodyear made tires, they made buttons. David was in the Navy. Buttons from his and other servicemen’s uniforms are in a design commemorating the armed services.

GARDEN

Outside the button house, visitors find Swiss style gardens. These are maintained by the Warther family. While the children were growing up, she had a vegetable patch from which she canned the produce to feed her family throughout the year. Later these gardens became the home of perennials. These beds, Swiss-styled, still contain some of the original plants.

Besides being an avid gardener, Frieda supported her husband on all his endeavors including traveling to see him while he was on the road. She had strong passions for educating others and helping her community of Dover. At her home, she held wreath-making classes, flower arranging, and jewelry making. Frieda was a 4-H leader, Sunday school teacher, and founder of the Dover Garden Club.

Visitors also see a grape arbor in the center of the garden, which was the family’s favorite spot to gather each Sunday. The adults visited while the children played on the homemade playground or in the sandbox. It was common to have ice cream there. Built in 1916, the original vine is still present as is the cement table Mooney salvaged.

It is part of the eight acres of park. Families can enjoy picnics on the grounds; play on an authentic hand-car, steam engine or the 1927 B&O caboose; and enjoy the gazebo’s shade.

KNIFE SHOP

Take the ramp to the knife shop’s gift store. It carries all types of Warther knives, cutting boards, and kitchen decor. The newest knives are a paring knife with a bird’s beak and a 7-inch Sanku. The Sanku has an upward tip and is a little more versatile than French knives.

Each knife goes through 32 manufacturing processes making them very high quality. It’s the last knife-making company in the United States to hand-grind their knives. The company provides free sharpening of every knife it sells.

Celebrities from both Bushes to Reagan have been known to purchase Warther knives. Others are Ted Kennedy, Condoleezza Rice, Perry Como, Frank Lloyd Wright, and the Timken family.

When Mooney’s son, David, returned from World War II, he took over E. Warther & Sons knife making business. David later expanded the company in the 1950's by tapping into corporate gift programs at such firms as Ford, Hedrich Blessing, and Timken. He incorporated the business in 1954 as E. Warther & Sons, Inc. It was also David who dedicated his life to creating the present museum layout to showcase his father’s life and works. Members of the family’s third and fourth generation, such as Steven Cunningham, President of Warther Cutlery, work in the knife shop.

DETAILS:

The Warther Museum is located at 331 Karl Avenue, Dover, Ohio. Their telephone number is (330) 343-7513. It’s open daily during January and February from 10:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. and the rest of the year from 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Their admission prices are adults $13.50, students (6-17) $5. The final tour takes place an hour before closing. Parking is free.

For those who visit Dover in November, enjoy their 25th Tree Festival which is open to the public and raises funds for the community’s local hospital. It runs from Saturday, November 10 from 11:00 a.m. to 8:00 p.m. through Sunday, November 18, closing at 5:00 p.m. Come see the myriad of Christmas trees and their ornaments inside the museum prepared by individuals and organizations. All are for sale. Warthers decorates the grounds. Admission is $5 for adults.

FREE NOTIFICATION SERVICE

If you want to be notified of new articles, go to the Contact Form on this web site. To sign up, it’s required to provide your NAME, CITY, and STATE along with your request. Personal information and emails are never given out, \and there is no charge for this service.

South of Canton, in the town of Dover, one museum has attracted visitors for decades, The Warther Museum. It’s Mooney Warther’s 64 impeccable carvings which trace the history of steam locomotives that’s the main draw. They start in 250 B.C. with Hero’s Engine and end with the Union Pacific Big Boy Locomotive of 1941. All are hand carved to scale with many moving parts. They were accomplished between 1905 and 1971 when he was between the ages of 20 and 86.

A tour of the house, a building full of incredible button designs, Swiss gardens, and a peek into the Warthers lives contribute to making this a not to be missed wonder in Northeast Ohio. To call it an attraction, fails to give it the dignity that Warthers deserves.

The Smithsonian Institute has appraised Warther’s carvings as priceless. They found his contrast of color, sense of proportion, and attention to detail is what makes the collection a true work of art. They also called it a one of a kind.

In 2016, the local newspaper, The Times Reporter, ran a Reader’s Choice Contest. The museum took third place for Best of the Best People and Places. It has been called a AAA Gem attraction and a 5 Star TripAdviser attraction.

ERNEST “MOONEY” WARTHER

Ernest “Mooney” Warther was born October 30, 1885 in a one-room schoolhouse in Dover, Ohio. He used to tell people that was why he didn’t need much formal education. When he was three, his father died, leaving his mother with five children, twenty cents, and a cow. From age five through fourteen, he herded cows for a penny apiece for area families. That is why he received his nickname “Mooney” from the Swiss word “Moonay” meaning “Bull of the herd.”

At the age of five, while taking the cows out to the pasture, he discovered a rusty jackknife in the field. He took it home and started whittling. When Mooney turned ten, a hobo gave him a block of wood with ten cuts that made a working set of pliers. Mooney sat down and figured out how to make one for himself. By the time he was in his twenties, he could carve a working pliers in under twenty seconds. They became his calling card. He gave one to every child who visited his shop or museum. Pliers are still cut by family members and are available for sale.

In the museum’s theater, you’ll see the walnut plier tree he made in 1913 at age 28. Considered to be his “Grand Finale” of whittling, the sculpture consists of 511 interconnected pliers out of one block of wood. Mooney carved it over 64 days, one hour a day, placing 31,000 cuts into the wood. No shaving was ever removed from it nor are there pins or glue holding it together,

The tree has only been retracted into its closed position once. This was done for Robert Ripley at the 1933 Chicago’s World Fair. The piece was so unique that Ripley of Ripley’s Believe it or Not wanted it for his museum. It has been featured in McGraw-Hill algebra book as an example of perfect geometric progression. You can see it at the museum today. On the wall, visitors view a triple set of pliers with 32 cuts and seven pliers formed from 82 cuts.

Having only a second grade education and no formal art or carving lessons, Warther concentrated on teaching himself. He read every book that he could find and could quote Bible verses. “He would read encyclopedias until they were worn out,” said Jean Nadeau, our guide.

As a teenager, his love for the railroad and steam engines became his focus for carving. He quickly ceased being a stranger to the railroad yards and maintained an extensive library of repair manuals from the roundhouses. These proved invaluable in crafting his intricate models.

He believed steam engines had advanced civilization more than any other invention and were never used for warfare. He also wanted to carve something mechanical and felt strongly that the steam engine satisfied that desire.

He was fourteen when he lied about his age and started working as a scrap bundler at American Sheet and Tin Plate Company, the local steel mill where he worked for 24 years. He eventually worked his way up to head shearsman. The mill, located a mile south of the museum, stopped operating in 1931.

You can see his animated model of this mill complete with 17 figures in the museum’s Early Years Room. It includes a figure of a man eating rhubarb pie and Swiss cheese at lunch because the man always did. Motion is conducted via leather sewing machine belts and a series of pulleys. It was one of five models that he made of this scene. He carved this one in 1952.

Through his reading, he learned ebony and ivory were found inside Egyptian tombs. Wanting his train carvings to permanently last, he used these same materials. Mooney’s motto was “Build everything to last forever.”

He made his earliest carvings from walnut wood using beef soup bones for white trim. On 14 of these, he later recarved the bone pieces out of ivory. In 1923, he started to purchase ivory. He obtained that material first from chipped billiard balls and then from the tusks of elephants who had died naturally. He used hippopotamus ivory (the finest type available), only once - when he carved Lincoln’s Funeral Train.

Mooney used his wife’s broaches and gemstones for smaller details such as lantern lights. For a lot of the trim work, he used mother of pearl and abalone shell. He used Arguto Oilless Bearing Company wood which is naturally oil-impregnated. It solved the problem of lubricating the moving pieces so his carvings would never need oil.

When Warther carved the history of steam locomotives, all parts were created using hand saws, files, eggbeater drills, and his handmade knives. It was not until his mid 70's, when the density of ebony and walnut became a problem for him, that he used his first power tool, a Delta Milwaukee drill press. He pressed the parts together or used pins but never glue since the old glues weren’t permanent. Everything was made to the scale of one-half inch equals one foot. All was done by free hand without a lathe.

Mooney set a goal based on the number of pieces and knowing how much time it would take him to carve that many pieces. There were very few carvings where he missed his goals. He kept drawings, notes, and plans in his personal journals, documenting his days and the progression of his collection. One carving was done at a time.

Viewing the carvings, you’ll quickly discover that he was a mathematical and mechanical genius. His locomotive models are to scale, inside and out, for locomotives and box cars. Such elements as cab interiors and mechanical movements are accurate. All models feature working pistons, flyrods, and wheels powered from underneath by a small electric motor and a sewing machine belt. There are many non motorized moving parts as well. Bells swing. Couplers open and close. The valves on the piping are pinned. Nuts, bolts, and rivets are in ivory. It is said that no engineer ever found any part missing in any way, shape, or form.

At the age of 25, on October 29, 1910, he married Frieda. They had five children. Today many third and fourth generation Warthers are carvers or active with the museum. Among those are granddaughter Carol, who runs the business, and David, a grandson, who has his own museum where he has traced the history of sailing ships.

By the 1920's, Warther carved constantly and was developing a reputation. In 1923, the Cleveland Plain Dealer ran a story about Warther and 15 models he had made. Alfred Smith, president of the New York Central Railroad, was so intrigued that he sent representatives to Dover to meet Warther. Mooney went with them to New York to promote their “Service Progress Special” railroad tour. When people came on board to see his carvings, he would explain why they needed to take the train. He traveled the rails with his collection for six months. Then he lived in New York City for 2-1/2 years while the collection was shown at Grand Central Station. After doing this to get money for his ivory, Warther returned home in 1926.

The railroad offered him $50,000 for his collection and $5,000 a year to live in New York. Henry Ford also proposed to pay him a handsome sum. However, Warther turned these offers down since he never wanted to sell any of his pieces. He did give 17 carvings away. All were returned except for two, and the family knows where they are.

After working for the railroad, Mooney’s brother Fred put the models in the back of a used truck he designed. The special truck had shelving and was on a Graham chassis. Charging ten cents admission to the exhibit, he drove this traveling train museum for 30 years throughout all of the states from 1927 to 1957.

Mooney did not always go on the road with his brother. He remained home carving and making knives for a living.

He had not been satisfied with store-bought knives when he began his carving. They didn’t conform to his hand or hold their edge well when carving such materials as ebony, ivory, and walnut. To satisfy his needs, he designed his own carving knives with 139 interchangeable blades, each with a different cutting profile. Blades were about an inch long, locked into place, and kept in the handle. These are on display at the museum.

In 1902, finding that Mooney’s knives held their sharpness, his mother asked him to make her a paring knife. Mooney made her one for Mothers’ Day. Neighbors soon ordered them. By 1923, he quit his job in the mill and devoted his time to his hobby of carving and to making kitchen knives.

To support his carvings, Warther started the Warther Kitchen Cutlery business which exists at the museum today. His three inch “Old Faithful” paring knife, that he first made in 1905, is a best seller today. The trademark of a swirl on the blade has also continued.

During World War II, he designed 1,100 knives for soldiers. A neighbor asked Mooney to make a knife to protect her husband. Today, during May and September only, you can see a collection of these knives. Twelve are shown with different size blades. Some handles of leather were made on request by specific individuals.

At age 68, he finished making steam engines and refused to carve diesels. He stopped working for four years before turning to historical events such as the carving of the Golden Spike and Lincoln’s funeral train.

On June 8, 1973, Mooney Warther died at the age of 87 due to a stroke. He was working on the Lady Baltimore & Ohio. This unfinished piece can be seen at the museum today.

LOBBY AND SHOP AT THE MUSEUM

The Warthers Museum opened in May 1936. Its first addition was in June 1988 with a building expansion in 2002. Tours last from slightly over an hour to 1-1/2 hours and are held upon request rather than on a regular schedule.

While waiting for the tour, observe the lobby exhibits. You will see a portrait of Mooney carving Abraham Lincoln’s funeral train during 1964-65 as well as photos of him giving pliers to General Omar Bradley and his 1954 meeting with President Nixon. You will also see a bust of Mooney by Walter Senz done in Cleveland in 1963. It was awarded to Warther at Crater Stadium in Dover.

Upon entering the museum, you can peek through the door at Mooney’s 1912 shop. It was in this shop that Mooney built a fireplace so he could temper steel and make knives. The fireplace did not have a bellows. Mooney depended upon its updraft.

On the walls and ceiling, you will find a collection of 5,000 arrowheads and points placed into numerous designs. Eighty-five percent of these are local. Mooney bought, traded, and bartered for them. He also would take weekly walks with his wife, Frieda, and their children through valleys and fields to collect them. Frieda would place these arrowheads into designs which visitors see today.

The shop also contains lots of reference books and a drawer full of various types of sandpaper ranging from coarse to fine. Plenty of tools are placed around the shop as well. He made his own tools with handles to fit his hand so he could work for longer periods of time.

Warther carved 64 steam locomotives at the rate of 1,000 pieces for them a month. It was not uncommon for him to work in the shop for 12 hours a day, six days a week starting at 2:00 or 3:00 a.m. He spent half of the time on carving and half on making knives.

THE EARLY YEARS ROOM

Besides Warther’s animated mill, this room houses some of his early works. Take time to watch the short video in the theater about Mooney’s life.

On display, is Mooney’s favorite, the Empire State locomotive #999, which he carved five times out of different materials. The eight- foot model took Mooney one year and four days to carve. Its sits on blocks made of ebony with ivory mortar. He gave his son David one of these as a newlywed present. David picked the pieces apart to show how extensive the model was.

The actual locomotive was the fastest one in the world at one time. While hauling the Empire State Express on May 10, 1893, it reached a speed of 112-1/2 miles per hour.

HISTORY ROOM

In this room, you will discover several extensive carvings and can watch a 10 minute video about Warther. These are ones he worked on when he was tracing the evolution of steam from 250 B.C. up to the 1900's. Carvings grew in size from several hundred to several thousand pieces as his work became more intricate.

Mooney considered his masterpiece the Great Northern Mountain Type 4-8-4 locomotive which he carved between September 1932 and May 1933. It consisted of 7,752 parts. He used abalone pearl in the wheel covers and on the logo in the cab’s side. The handwriting on the ivory base inlay was his. A lot of its pieces move and the volume of fittings in it is incredible. The actual train was designed and built by the Baldwin Locomotive Works.

The first of his models to use ebony was the New York Central Lines 4-6-4 Hudson type locomotive. The American Locomotive Company designed the engine in 1927 to haul trains providing Limited service. Carved in eight months, it had 7,332 pieces. Warther also created the bases and rails for his pieces.

The Mallet Articulated Triplex Compound locomotive consisted of 1,504 pieces. It took him 9-1/2 months to carve and was completed in 1931. The engine was built for the Erie Railroad by the Baldwin Locomotive Works in 1913.

The first passenger Mogul locomotive was built for the 1876 Centennial Exposition. It traveled at 50 mph. The Atlantic Type Locomotive A was a prize winning engine at the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904. Its speed was 90 mph.

Another carving was of the 1941 Union Pacific Big Boy built by American Locomotive Works. Completed on Mooney’s 68th birthday. When he finished this one, he announced he had completed carving the evolution of steam. Currently, the city of Cheyenne, Wyoming is rebuilding an American locomotive. It will weigh 604 tons.

Warther did many smaller historic models, too, that can be seen in this room. Among the earliest associated with steam engines are Hero’s engine from 250 B.C. in Alexandria, Egypt and Whirling Aeolipile from Greece’s first century A.D.

Others include Leonardo Da Vinci’s steam engine from Milan, Italy in the late 15th century, Branca’s steam turbine from Rome in 1629, and James Watts condensing engine from London in 1774. On display is a model of Sir Isaac Newton’s proposed locomotive in 1680 and Newcomen’s Atmospheric engine from England in 1705. He also carved Trevithick’s locomotive which was built in South Wales and was the first engine to run on rails in 1803. It had a speed of 5 miles per hour.

Others are DeWitt Clinton’s first locomotive of the New York Central Railroad dated 1831 and Old Ironsides, a model of Baldwin’s first locomotive in 1832. The carving of James Milholland’s Illinois locomotive, from 1852, the first passenger engine to burn anthracite coal, is also found. The Atlantic type locomotive was a prize winning engine at the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904. It had a speed of 90 miles per hour.

Mooney also carved three elephants. One is on display as is the cane he carved for Lindbergh. He also made walking canes and other gifts for Roosevelt, Omar Bradley,our last five star general Eisenhower, and Nixon.

IVORY ROOM

Ivory models are housed here. This includes his “Great Events in American Railroad History” done between the ages of 72 and 85. Among these are the Great Locomotive Chase of the Civil War, the Casey Jones locomotive, and the first passenger train, the John Bull.

It is also the home of his unfinished Lady Baltimore on which he was working when he died. The B&O was the first passenger train. It was exhibited at the 1876 Centennial Exposition and had a speed of 50 miles per hour.

Perhaps, the most famous one is Warther’s Lincoln’s funeral train. Mooney chose Lincoln as a father figure. Perhaps, that was because he lost his own father at so young an age. He liked Lincoln’s philosophy and read every book on his hero.

Taking one year to carve, everything about the Lincoln funeral train is historically correct. Mooney finished it on the 100th anniversary of the assassination in 1885. He has Lincoln lying in a coffin. The presidential seal has scrimshaw engraved in the ivory oval. There are mother of pearl accents at the bottom of each car.

Mooney also carved the Golden Spike event though it is not historically accurate. He had President Grant smoking a cigar though Grant was never there. Mooney commented, “He should have been there.”

He also has a Native American in the scene. None were present. Mooney stated that in respect for the Native Americans he placed an Indian there since it was their territory. His spike is gold, which he received from a dentist, Dr. O. K. Brown.

One model he did, the #999, was eight feet long and weighed 81 pounds. It was made up of 11,000 pieces with 4,000 of those making up the bridge on which it sat. He did it at the age of 76. It took him a year and four days.

WARTHER HOME

Outside the museum, you will find a burnt brick home moved into by the Warthers in 1912. Their oldest daughter, Florence, lived there until 2005. The home has been restored to the 1920's. Visitors only see the downstairs portion of the kitchen, dining room, library, and parlor since the three bedrooms upstairs aren’t on the tour. Most of the pieces belonged to the family. Almost all woodwork is original.

The parlor is typical early 1900s with a radio receiver, spinning wheel, doll carriage, and Victrola. They never had a television as Mooney felt it was too time consuming. The stove and sink dominate the kitchen. A table glides open to widen and become different sizes.

Mooney soon discovered that it was too cold to work in the shop he had built. He moved his tools inside and set up his carving in the library. He had his models all over the house. In 1951, he built the brick building known as the button house and took his carvings there.

BUTTON HOUSE

Frieda Warther was born in Switzerland in 1890. The family moved to Dover when she was four years old. Being the oldest girl of 13 children, she earned the gift of her mother’s button box, a European tradition that gave the eldest daughter a box full of buttons and sewing tools. She collected many buttons from girls who gave away their mothers’ boxes.

In addition to creating designs with arrowheads, Frieda collected over 130,000 buttons between the ages of nine and 90. You’ll find 73,000 are mounted at the museum’s button house. Before being placed into designs, these were separated by size, color, and style.

By the 1950's, when the children had grown up, Frieda set up the dining room to make her button designs. She used paper drawings and a homemade compass to design her layouts, Then she would take squares of Marlite, drill holes, and attach her button design on the Marlite using dental floss, carpet thread, and some glue. Visitors see holes in the dining room table today where she drilled too deeply.

Her 47 designs can be seen covering all four walls of the Button House. They’re composed of buttons of various types. In 1992, David, the Warther's youngest son, redid these. They’re now attached by colored wires to Corian counter top material

The buttons are of various types. The calico buttons are made to look like cloth and come in hundreds of designs. Celluloid buttons were created from the late 1800's to the 1920's. They are a composite of plastic and plant-based resin. Her cameo buttons represent such women as Egyptian queens, Lady Liberty, and Queen Elizabeth the Second.

Brass buttons had to go through a process so they would not tarnish and deteriorate. Horse bridle buttons came from horse bridles. One design is made of Goodyear rubber buttons. Before Goodyear made tires, they made buttons. David was in the Navy. Buttons from his and other servicemen’s uniforms are in a design commemorating the armed services.

GARDEN

Outside the button house, visitors find Swiss style gardens. These are maintained by the Warther family. While the children were growing up, she had a vegetable patch from which she canned the produce to feed her family throughout the year. Later these gardens became the home of perennials. These beds, Swiss-styled, still contain some of the original plants.

Besides being an avid gardener, Frieda supported her husband on all his endeavors including traveling to see him while he was on the road. She had strong passions for educating others and helping her community of Dover. At her home, she held wreath-making classes, flower arranging, and jewelry making. Frieda was a 4-H leader, Sunday school teacher, and founder of the Dover Garden Club.

Visitors also see a grape arbor in the center of the garden, which was the family’s favorite spot to gather each Sunday. The adults visited while the children played on the homemade playground or in the sandbox. It was common to have ice cream there. Built in 1916, the original vine is still present as is the cement table Mooney salvaged.

It is part of the eight acres of park. Families can enjoy picnics on the grounds; play on an authentic hand-car, steam engine or the 1927 B&O caboose; and enjoy the gazebo’s shade.

KNIFE SHOP

Take the ramp to the knife shop’s gift store. It carries all types of Warther knives, cutting boards, and kitchen decor. The newest knives are a paring knife with a bird’s beak and a 7-inch Sanku. The Sanku has an upward tip and is a little more versatile than French knives.

Each knife goes through 32 manufacturing processes making them very high quality. It’s the last knife-making company in the United States to hand-grind their knives. The company provides free sharpening of every knife it sells.

Celebrities from both Bushes to Reagan have been known to purchase Warther knives. Others are Ted Kennedy, Condoleezza Rice, Perry Como, Frank Lloyd Wright, and the Timken family.

When Mooney’s son, David, returned from World War II, he took over E. Warther & Sons knife making business. David later expanded the company in the 1950's by tapping into corporate gift programs at such firms as Ford, Hedrich Blessing, and Timken. He incorporated the business in 1954 as E. Warther & Sons, Inc. It was also David who dedicated his life to creating the present museum layout to showcase his father’s life and works. Members of the family’s third and fourth generation, such as Steven Cunningham, President of Warther Cutlery, work in the knife shop.

DETAILS:

The Warther Museum is located at 331 Karl Avenue, Dover, Ohio. Their telephone number is (330) 343-7513. It’s open daily during January and February from 10:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. and the rest of the year from 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Their admission prices are adults $13.50, students (6-17) $5. The final tour takes place an hour before closing. Parking is free.

For those who visit Dover in November, enjoy their 25th Tree Festival which is open to the public and raises funds for the community’s local hospital. It runs from Saturday, November 10 from 11:00 a.m. to 8:00 p.m. through Sunday, November 18, closing at 5:00 p.m. Come see the myriad of Christmas trees and their ornaments inside the museum prepared by individuals and organizations. All are for sale. Warthers decorates the grounds. Admission is $5 for adults.

FREE NOTIFICATION SERVICE

If you want to be notified of new articles, go to the Contact Form on this web site. To sign up, it’s required to provide your NAME, CITY, and STATE along with your request. Personal information and emails are never given out, \and there is no charge for this service.

Entrance to Warthers Museum

Statue of Mooney by Walter Senz

Mooney's Shop

Mooney's Workshop Next to the House

Close up of One of the Arrowhead Designs

Mill Scene of American Steel and Tin Company

In Early Years Room - Empire State Express Which He Carved Five Times

Overall View of the History Room

Great Northern Locomotive - 7,752 Parts

The Great Northern Close Up

New York Central

Mallet Type by American Locomotive Works for the Union Pacific Railroad

Mallet Articulated Triplex Compound Locomotive

The First Passenger Mogul

Atlantic Type Locomotive A

DeWitt Clinton

Branca's Steam Turbine DaVinci's Steam Engine Whirling Aeolipile from Greece

James Milholland's Illinois

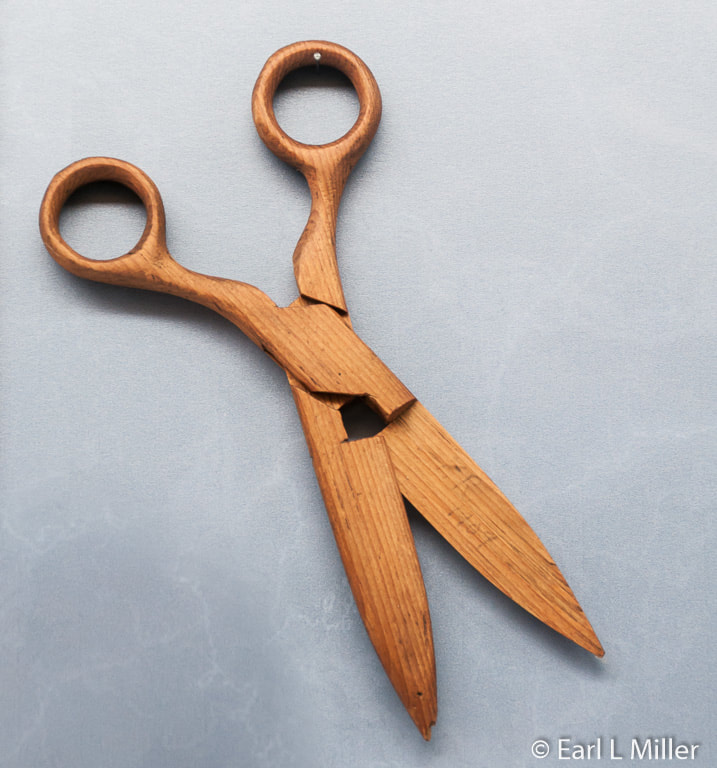

A Scissors From One Piece of Wood

Ivory Room - The Golden Spike

Lincoln's Funeral Train

The Nashville, Pulled Lincoln's Funeral Train

The Baltimore and Ohio - The Last Train Mooney Was Working On

The Warther Home

The Dining Room Where Freida Made Her Button Designs

Button House

Interior of the Button House

Close Up of One of Freida's Many Designs in the Button House

Frieda's Design to Honor the United States Navy

The Garden Where the Warther Family Liked to Relax

Making Cutting Boards in the Knife Shop

Sharpening Knives