Hello Everyone,

Sometimes a talent passes from generation to generation. Ernest “Mooney” Warther brilliantly carved the history of steam engines. His son, David, mastered the art of making knives. David II is following in their footsteps but on a different topic. He is transforming the history of sailing ships from the dynasties of Egypt to present day into ebony and antique ivory models. You can watch him as he masterfully carves his latest creation at David Warther Carvings which displays his wonderful ships.

David’s work has received national recognition. The Mariner’s Museum of Newport News, Virginia said, “Extraordinarily exquisite carvings beyond compare.” Mystic Seaport’s curators in Mystic Seaport, Connecticut stated, “ Epitomizes the highest level of achievement in maritime art.” In 1996, he received the Governor’s Award for the Arts, the highest level that can be bestowed on an Ohio artist.

DAVID WARTHER

David is the fifth generation of carvers. His great-great-grandfather was a cabinet maker and woodcarver in Switzerland. His great grandparents immigrated to Dover, Ohio where David was born in 1959. The Warther Museum in Dover displaying Mooney’s exquisite carvings has been drawing crowds for generations.

At the age of three, David began carving from elephant tusk ivory. He carved his first ship at the age of six. It was a Viking longboat made of wood. Since that day, people have always spotted a ship carving on David’s workbench.

He credits his grandfather with allowing him to have the leftover scraps, the use of tools, and plenty of encouragement. His father taught him how to cut up ivory, how to file, and how to sandpaper the base.

David has always loved the beauty of the ship. His aim is to convey man’s progress in shipbuilding over the past 5,000 years. He sees the history of the ship as related to man’s progress on earth and wants to recreate this story in an art form that people can understand.

At age thirteen, he developed a unique hand filing and sanding process for making an ivory “string” for his ships’ riggings. It allowed him to make threads that are .007 of an inch in diameter, twice the thickness of a human hair.

David rests a strip of ivory in a small socket hole that has been drilled into a block of steel. To make the ivory round, he files and sands over the top of the groove with one hand while rotating the ivory with his other hand. The string is then placed into progressively smaller grooves until he achieves the proper size. To make a 9" thread, it takes around 90 minutes. By making a string, the ivory is flexible and easy to incorporate into the carving.

By age 17, David had made a number of smaller ship carvings. These lacked scale, accuracy, and intricate parts. He felt ready to do his first major carving. It took him over a year. It was a scale replica of the three masted bark, Coast Guard Academy training ship, the Eagle. David acquired blueprints and technical drawings from the Academy. Many drawings pertaining to the Eagle were original 1936 German drafts since it was built as a naval training ship for that country. David’s carving consisted of walnut wood trimmed with ebony, ivory, and mother-of-pearl.

After attending high school in Dover, during his late teen years, David studied the history of ship development. He later became a member of the Institute of Nautical Archaeology at Texas A&M University. He did not attend art school.

As he entered his twenties, he became enthralled with carving ships from 3000 B.C. in Egypt to modern times. It was then that he decided to dedicate himself to using ivory. Although no member of the family had done it before him, he decided to use scrimshaw ( ivory engraving) for his details. This method would create fine lines to convey such details as deck planking, doors, and windows.

With scrimshaw, he scores these lines with a handheld stylus on the polished ivory surface exposing a more porous area underneath. Then he applies ink to the area with a Q tip, lets it dry, and wipes off the excess color.

The ink wipes cleanly off the top surface so the ivory remains white. It does attach to the exposed material leaving fine lines and shapes. Styluses are made from sewing needles.

American whalers taught the Eskimos how to use scrimshaw to engrave details onto surface carvings. They would do it on bone, tooth, or ivory with sharp tools then apply a color to make the lines more visible and permanent. If they stippled close together, they got black. If dots were poked further apart, they created shades of grey.

His hull is always made from one piece of ivory. His bases are of ebony in the shape of a blunted pyramid. He has followed this design since he created his ship Eagle. Ancient Greeks created the design of having dark colors on the bottom and light shades on top.

Sections of ivory are cut from the tusks using a band saw. Jeweler saws are then used to cut the sections into rough shapes. Files, sandpaper, and fine scrapers are used to complete the final shaping. Knives are used to carve the figurehead and for intricate fittings of nearly all the parts. For polishing, tiny, spinning buffing wheels are used in a drill press.

David told us that each pair of tusks is a different shade. Tusks are like fingerprints to elephants. Because of this, he needs to make sure he has enough of the same ivory to complete his piece.

Ebony, which grows in west Africa, has a long history of uses dating back to ancient Egypt. It has a dense, flat texture that can be polished to a very smooth finish, making it highly valuable as an ornamental wood. David purchases it through a local Amish sawmill.

Shells of abalone, that he uses for decoration, have also been used for centuries as decorative items and as a source of mother-of-pearl for buttons, jewelry, and inlays. David cuts his own from shells that have been in his family since childhood.

Before carving, he does extensive research through long relationships with maritime museums, archaeologists, and historians. This enables him to acquire vintage photographs, original blueprints, and detailed schematics. He refers to these while carving to ensure that no detail is overlooked.

David works entirely with antique ivory, ebony, and abalone shell. The ivory he uses is classified as pre-ban and antique ivory. It is purchased or donated from other museums or private collections within the United States. All of this ivory was in this country before the late 1980s international trading ban went into effect. He personally contributes to wildlife conservation efforts regularly.

He is consulted by professionals who deal with antiques, musical instruments, and firearms about the sale and transfer of tusks and carvings. During the evenings, David makes his living by making parts for musical instruments. He carves his ships during the day.

Most of his ships are 8 to 10 inches long. They range in scale from 1/8 to 1/16 of an inch on the model for every foot on the real boat. He uses such tools as saws, files, and knives to create them.

Grandpa Mooney taught him how to use ivory pegs and pins to hold the carving together. Even the simplest of his ships are put together structurally with pegs and pins which takes a lot of extra time but ensures the carvings last forever. The pegs and pins are driven in, cut off, and polished.

He never uses any glue when assembling pieces except for the base. That is because ivory will outlive glue. Eventually, the glue would deteriorate and the carving would fall apart.

He has discovered that one of the most difficult aspects with working with such small parts is holding onto the materials as he shapes them. He will bond some of the smallest pieces on to wild cherry wood while he is carving. Cherry is a very weak wood so once the piece is completed, he can pop it off the handle and shave any remaining wood from the ivory.

During the 1980's, David’s carvings were displayed in major maritime museums in New England. Then in 2003, he opened his first David Warther Carvings. It was located in Sugarcreek, Ohio. David closed it in 2003 to move to an improved facility and concentrate on creating his best work. The new museum opened May 4, 2013.

He is currently working on his 86th piece. It is the Isaac Webb that sailed between New York City and Europe in the 1850's. It brought 800 passengers to Ellis Island. When finished, he hopes to have close to 100 carvings. Because of the level of detail, it can take David from two months to 1-1/2 years to complete a project.

TOUR DAVID WARTHER CARVINGS

The exhibit, with more than 80 ships, takes place in four rooms dedicated to different eras of shipbuilding. A fifth room, the Heritage Room, is dedicated to Mooney’s memory and displays David’s early carvings. The history starts with the Ancient room with its ancient Egyptian, Roman, Phoenician, and Greek ship carvings. The Medieval room features Viking ships. The Age of Exploration houses such ships as the Susan Constant and Mayflower while the Age of Sail contains modern ship carvings. These rooms surround David’s workshop.

The natural history display has a collection of various types of ivory ranging from wooly mammoth tusks and fossil walrus tusks, dating back 20,000 years, to elephant and hippopotamus tusks. It also has teeth from ancient and modern animals: a wooly mammoth, Arctic Narwhal (a whale), and mastodon. Look for a pair of African elephant tusks in the doorway. They weigh 130 pounds each and are the third largest pair of elephant tusks in the United States.

You’ll find the guides friendly and knowledgeable. Many are Amish or Mennonites. They describe how the carvings were constructed, give details on ship features and design, and provide a history of trade routes from the Medieval and Renaissance eras.

We were fortunate that David took time off from his work to explain his carvings and methods. His wife Maryruth took us through the Heritage Room. On a typical tour, David is almost always available to answer questions, greet visitors, and explain his carving techniques.

ANCIENT ROOM

The models in this room date from 3200 B.C. to 650 A.D. They depict ships from the ancient empires of Egypt, Greece, and Rome as well as from lesser known cultures in the Mediterranean Basin.

One of the oldest ships represented is Pharaoh Cheops' royal ship dated 2600 B.C. He was responsible for building the Great Pyramid of Giza. The craft was his personal luxury yacht that sailed up and down the Nile. It had no sails or oars as men towed it around. Upon his death, it was dismantled and buried in a stone vault, boat grave at the Great Pyramid’s base for his use in the afterlife. It was forgotten until rediscovered by accident in 1953 by a bus driver. It took 20 years to assemble and is now displayed in a museum at the base of the pyramids. David used plans and drawings from Egypt’s Cairo Museum to carve this vessel.

Another is the Royal Ship of Tutankamen dated 1335 B.C. This 88-foot royal yacht was owned by this famous Pharaoh who reigned from 1339 to 1327 B.C. Its hull was highly decorated with large stylized lotus flowers, strips, squares, and other geometric figures. The fore and aft castles (areas raised above the main deck) had royal symbols of the sphinx and bull carved into their side panels.

The Fifth Dynasty Egyptian ship represents an early Egyptian passenger ship. Egyptian ships were meant to travel the Nile and were made of wood.

Eye of the Sun was a Fifth Dynasty cargo vessel dated 2450 B.C. She sailed the Nile with a whole range of cargo for the Egyptians. This commonly included animals, pottery jugs of wine, beer, grains, and dried fruits. Clothing, bricks, wood, ivory tusks, and tools were among other items she carried. The ship sailed upstream with the wind and would return downstream with the current, aided by men with poles and long handled oars from the ship’s sides and front railing.

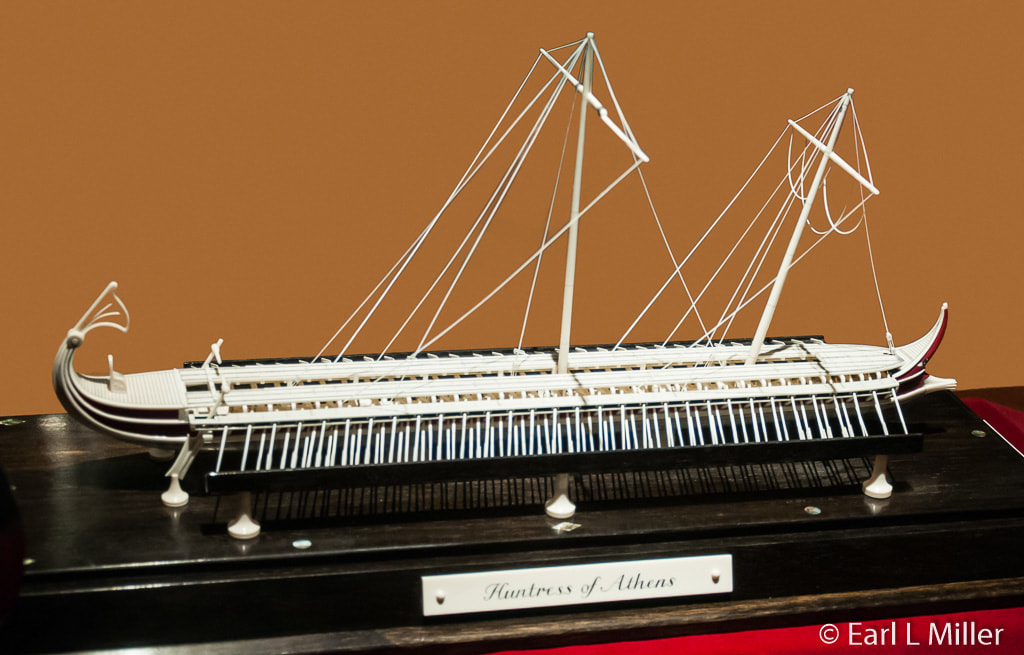

The Huntress of Athens was a 120 foot warship from 330 B.C. It had 170 oarsmen who each worked an oar at three different levels on the ship. Each level had from 27 to 31 oarsmen on each side. On this one, David bolted three pieces of ebony together.

MEDIEVAL ROOM

The carvings in this room are from 820 A.D. to 1500 A.D. They showcase ships from many European nations including England, Germany, the Netherlands, and France. During this period, little ships hugged the coast of Italy delivering cargo. They could be compared to today’s UPS trucks. The Italians made the most beautiful ships 1,000 years ago as their country was a center for art, design, and engineering.

Both the Gotland and the Gokstad are in the Viking Ship Museum in Oslo, Norway. The Gotland, dating from 1225, was the first to have a stern rudder The stern’s decorative ends and posts were removable so that dragon head carvings could be placed there during wartime. The carving has a split hull combining a bottom of ebony with a top of ivory.

The Goksrad was another Viking ship. It was constructed almost entirely of oak in 890 A.D. In 1881, it was found to be in remarkably good condition when discovered in a king’s burial mound in Gotland, Norway. A replica of it, made in 1893, crossed the Atlantic in 28 days.

A third ship in this room is the Oseberg. Built in 820 A.D., it was a pleasure craft used by a Viking Queen during her lifetime as a yacht for local excursions. It became a burial chamber for the queen and her handmaid in 834 A.D.. The ship was discovered in 1904, incredibly well preserved. Currently, it is in the Viking Ship Museum in Oslo.

The Valkyrie was 92 feet. It sailed out of Denmark as an armed merchant ship without cannon in 1370. Her men had bows and arrows, crossbows, and lances to ward off pirates. In time of war, a ship such as this would be required for state service of the merchant who owned her. The dragon on the figurehead and multi-colored designs on the castles indicate this ship was armed. The name Valykrie comes from Norse mythology.

The Loessi, an elegant merchant ship, sailed from Genoa in 1370 A.D. According to David, it represents the epitome of medieval ship building and design. He said that its fine lines and elegant features were seldom seen in other ships from the same time period. For example, it had glass windows, which were very rare, on the cabin’s front.

AGE OF EXPLORATION

The Spanish and Portuguese during the 1400's built ships with multiple masts and stronger hulls as they hoped to reach India and China. The Mataro ship was an early design in this effort. It was followed by the Caravels of the Nina and Pinta and the Naos like the Santa Maria.

During this period, all of the tourist business from Northern Europe to the Mediterranean was church related. The argument was where the wealthy should go next summer. The most popular locale was Jerusalem, followed by Rome, then St. James Burial Place in northern Spain.

Pilgrims chartered ships for the New World which were deadheaded one way. Ships like the Mayflower sailed back empty. The Susan Constant, the largest of three ships which went to Virginia, was a one way ticket for passengers headed for Jamestown but brought back precious minerals to England. The actual ship’s decoration on the hull’s exteriors were painted on. David has recreated them by scrimshawing them.

Vasco da Gama sailed on the Sao Gabriel from Portugal on a two-year journey to India in 1497. He was the first to link Europe and Asia by an ocean route connecting the west with the orient. This opened the way for global discovery and trade among many people.

David’s collection also includes Columbus’s three ships, Hudson’s Half Moon, Captain Cook’s Endeavor, Drake’s Golden Hinde, the H.M.S. Bounty, and the Mayflower.

THE MODERN SHIPS

It’s on David’s showcase of modern ships, more than his other carvings of earlier eras, that his elegant ivory rigging lines are more evident. At the diameter of the thickness of only two human hairs, ivory will bend enough to give him the curved lines he desires in each carving’s superstructure.

One of his carvings is of the U.S.S. Constitution, one of six heavy frigates authorized in 1794 to form the U.S. Navy. She had a 57 year career before retiring as a U.S. Naval training ship. She is the oldest commissioned ship in the Navy. Residing today in Boston Harbor, she is open to the public.

Another is of the Niagara, the relief flagship that Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry captained during the Battle of Lake Erie on September 10, 1813 during the War of 1812. She was one of the nine ships that defeated a British squadron of six vessels. The victory secured the Northwest Territory and lifted the nation’s morale. Her cannon barrels were cast in Pittsburgh while the ship was built near Erie, Pennsylvania.

HERITAGE ROOM

Maryruth, David’s wife, gave us a tour of the Heritage Room which honors David’s grandfather, Mooney Warther. You can see one of the five steel mills Mooney made and a photo of him and his brother at the mill.

It also contains some of the commando knives David’s father made and some kitchen cutlery. The cane is a replica of the one Mooney made for Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

The room houses David’s early ships which his mother kept. He used matchsticks and toothpicks instead of ivory for rigging on these. You can also view the Corsair he made after crafting his first ship.

DETAILS

You will find this 10,000 square foot museum between the villages of Sugarcreek and Walnut Creek, Ohio at 1775 State Route 39. The telephone number is (330) 852-6096. Admission is $10 for adults; $5 for ages 5-18, and free for under age 5. Hours from April through October are Monday through Saturday 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. They are open during the winter from 10:00 a.m. to 4:00 Thursday through Saturday. Closed year round on Sunday. Visit David's web site to see even more carvings.

Sometimes a talent passes from generation to generation. Ernest “Mooney” Warther brilliantly carved the history of steam engines. His son, David, mastered the art of making knives. David II is following in their footsteps but on a different topic. He is transforming the history of sailing ships from the dynasties of Egypt to present day into ebony and antique ivory models. You can watch him as he masterfully carves his latest creation at David Warther Carvings which displays his wonderful ships.

David’s work has received national recognition. The Mariner’s Museum of Newport News, Virginia said, “Extraordinarily exquisite carvings beyond compare.” Mystic Seaport’s curators in Mystic Seaport, Connecticut stated, “ Epitomizes the highest level of achievement in maritime art.” In 1996, he received the Governor’s Award for the Arts, the highest level that can be bestowed on an Ohio artist.

DAVID WARTHER

David is the fifth generation of carvers. His great-great-grandfather was a cabinet maker and woodcarver in Switzerland. His great grandparents immigrated to Dover, Ohio where David was born in 1959. The Warther Museum in Dover displaying Mooney’s exquisite carvings has been drawing crowds for generations.

At the age of three, David began carving from elephant tusk ivory. He carved his first ship at the age of six. It was a Viking longboat made of wood. Since that day, people have always spotted a ship carving on David’s workbench.

He credits his grandfather with allowing him to have the leftover scraps, the use of tools, and plenty of encouragement. His father taught him how to cut up ivory, how to file, and how to sandpaper the base.

David has always loved the beauty of the ship. His aim is to convey man’s progress in shipbuilding over the past 5,000 years. He sees the history of the ship as related to man’s progress on earth and wants to recreate this story in an art form that people can understand.

At age thirteen, he developed a unique hand filing and sanding process for making an ivory “string” for his ships’ riggings. It allowed him to make threads that are .007 of an inch in diameter, twice the thickness of a human hair.

David rests a strip of ivory in a small socket hole that has been drilled into a block of steel. To make the ivory round, he files and sands over the top of the groove with one hand while rotating the ivory with his other hand. The string is then placed into progressively smaller grooves until he achieves the proper size. To make a 9" thread, it takes around 90 minutes. By making a string, the ivory is flexible and easy to incorporate into the carving.

By age 17, David had made a number of smaller ship carvings. These lacked scale, accuracy, and intricate parts. He felt ready to do his first major carving. It took him over a year. It was a scale replica of the three masted bark, Coast Guard Academy training ship, the Eagle. David acquired blueprints and technical drawings from the Academy. Many drawings pertaining to the Eagle were original 1936 German drafts since it was built as a naval training ship for that country. David’s carving consisted of walnut wood trimmed with ebony, ivory, and mother-of-pearl.

After attending high school in Dover, during his late teen years, David studied the history of ship development. He later became a member of the Institute of Nautical Archaeology at Texas A&M University. He did not attend art school.

As he entered his twenties, he became enthralled with carving ships from 3000 B.C. in Egypt to modern times. It was then that he decided to dedicate himself to using ivory. Although no member of the family had done it before him, he decided to use scrimshaw ( ivory engraving) for his details. This method would create fine lines to convey such details as deck planking, doors, and windows.

With scrimshaw, he scores these lines with a handheld stylus on the polished ivory surface exposing a more porous area underneath. Then he applies ink to the area with a Q tip, lets it dry, and wipes off the excess color.

The ink wipes cleanly off the top surface so the ivory remains white. It does attach to the exposed material leaving fine lines and shapes. Styluses are made from sewing needles.

American whalers taught the Eskimos how to use scrimshaw to engrave details onto surface carvings. They would do it on bone, tooth, or ivory with sharp tools then apply a color to make the lines more visible and permanent. If they stippled close together, they got black. If dots were poked further apart, they created shades of grey.

His hull is always made from one piece of ivory. His bases are of ebony in the shape of a blunted pyramid. He has followed this design since he created his ship Eagle. Ancient Greeks created the design of having dark colors on the bottom and light shades on top.

Sections of ivory are cut from the tusks using a band saw. Jeweler saws are then used to cut the sections into rough shapes. Files, sandpaper, and fine scrapers are used to complete the final shaping. Knives are used to carve the figurehead and for intricate fittings of nearly all the parts. For polishing, tiny, spinning buffing wheels are used in a drill press.

David told us that each pair of tusks is a different shade. Tusks are like fingerprints to elephants. Because of this, he needs to make sure he has enough of the same ivory to complete his piece.

Ebony, which grows in west Africa, has a long history of uses dating back to ancient Egypt. It has a dense, flat texture that can be polished to a very smooth finish, making it highly valuable as an ornamental wood. David purchases it through a local Amish sawmill.

Shells of abalone, that he uses for decoration, have also been used for centuries as decorative items and as a source of mother-of-pearl for buttons, jewelry, and inlays. David cuts his own from shells that have been in his family since childhood.

Before carving, he does extensive research through long relationships with maritime museums, archaeologists, and historians. This enables him to acquire vintage photographs, original blueprints, and detailed schematics. He refers to these while carving to ensure that no detail is overlooked.

David works entirely with antique ivory, ebony, and abalone shell. The ivory he uses is classified as pre-ban and antique ivory. It is purchased or donated from other museums or private collections within the United States. All of this ivory was in this country before the late 1980s international trading ban went into effect. He personally contributes to wildlife conservation efforts regularly.

He is consulted by professionals who deal with antiques, musical instruments, and firearms about the sale and transfer of tusks and carvings. During the evenings, David makes his living by making parts for musical instruments. He carves his ships during the day.

Most of his ships are 8 to 10 inches long. They range in scale from 1/8 to 1/16 of an inch on the model for every foot on the real boat. He uses such tools as saws, files, and knives to create them.

Grandpa Mooney taught him how to use ivory pegs and pins to hold the carving together. Even the simplest of his ships are put together structurally with pegs and pins which takes a lot of extra time but ensures the carvings last forever. The pegs and pins are driven in, cut off, and polished.

He never uses any glue when assembling pieces except for the base. That is because ivory will outlive glue. Eventually, the glue would deteriorate and the carving would fall apart.

He has discovered that one of the most difficult aspects with working with such small parts is holding onto the materials as he shapes them. He will bond some of the smallest pieces on to wild cherry wood while he is carving. Cherry is a very weak wood so once the piece is completed, he can pop it off the handle and shave any remaining wood from the ivory.

During the 1980's, David’s carvings were displayed in major maritime museums in New England. Then in 2003, he opened his first David Warther Carvings. It was located in Sugarcreek, Ohio. David closed it in 2003 to move to an improved facility and concentrate on creating his best work. The new museum opened May 4, 2013.

He is currently working on his 86th piece. It is the Isaac Webb that sailed between New York City and Europe in the 1850's. It brought 800 passengers to Ellis Island. When finished, he hopes to have close to 100 carvings. Because of the level of detail, it can take David from two months to 1-1/2 years to complete a project.

TOUR DAVID WARTHER CARVINGS

The exhibit, with more than 80 ships, takes place in four rooms dedicated to different eras of shipbuilding. A fifth room, the Heritage Room, is dedicated to Mooney’s memory and displays David’s early carvings. The history starts with the Ancient room with its ancient Egyptian, Roman, Phoenician, and Greek ship carvings. The Medieval room features Viking ships. The Age of Exploration houses such ships as the Susan Constant and Mayflower while the Age of Sail contains modern ship carvings. These rooms surround David’s workshop.

The natural history display has a collection of various types of ivory ranging from wooly mammoth tusks and fossil walrus tusks, dating back 20,000 years, to elephant and hippopotamus tusks. It also has teeth from ancient and modern animals: a wooly mammoth, Arctic Narwhal (a whale), and mastodon. Look for a pair of African elephant tusks in the doorway. They weigh 130 pounds each and are the third largest pair of elephant tusks in the United States.

You’ll find the guides friendly and knowledgeable. Many are Amish or Mennonites. They describe how the carvings were constructed, give details on ship features and design, and provide a history of trade routes from the Medieval and Renaissance eras.

We were fortunate that David took time off from his work to explain his carvings and methods. His wife Maryruth took us through the Heritage Room. On a typical tour, David is almost always available to answer questions, greet visitors, and explain his carving techniques.

ANCIENT ROOM

The models in this room date from 3200 B.C. to 650 A.D. They depict ships from the ancient empires of Egypt, Greece, and Rome as well as from lesser known cultures in the Mediterranean Basin.

One of the oldest ships represented is Pharaoh Cheops' royal ship dated 2600 B.C. He was responsible for building the Great Pyramid of Giza. The craft was his personal luxury yacht that sailed up and down the Nile. It had no sails or oars as men towed it around. Upon his death, it was dismantled and buried in a stone vault, boat grave at the Great Pyramid’s base for his use in the afterlife. It was forgotten until rediscovered by accident in 1953 by a bus driver. It took 20 years to assemble and is now displayed in a museum at the base of the pyramids. David used plans and drawings from Egypt’s Cairo Museum to carve this vessel.

Another is the Royal Ship of Tutankamen dated 1335 B.C. This 88-foot royal yacht was owned by this famous Pharaoh who reigned from 1339 to 1327 B.C. Its hull was highly decorated with large stylized lotus flowers, strips, squares, and other geometric figures. The fore and aft castles (areas raised above the main deck) had royal symbols of the sphinx and bull carved into their side panels.

The Fifth Dynasty Egyptian ship represents an early Egyptian passenger ship. Egyptian ships were meant to travel the Nile and were made of wood.

Eye of the Sun was a Fifth Dynasty cargo vessel dated 2450 B.C. She sailed the Nile with a whole range of cargo for the Egyptians. This commonly included animals, pottery jugs of wine, beer, grains, and dried fruits. Clothing, bricks, wood, ivory tusks, and tools were among other items she carried. The ship sailed upstream with the wind and would return downstream with the current, aided by men with poles and long handled oars from the ship’s sides and front railing.

The Huntress of Athens was a 120 foot warship from 330 B.C. It had 170 oarsmen who each worked an oar at three different levels on the ship. Each level had from 27 to 31 oarsmen on each side. On this one, David bolted three pieces of ebony together.

MEDIEVAL ROOM

The carvings in this room are from 820 A.D. to 1500 A.D. They showcase ships from many European nations including England, Germany, the Netherlands, and France. During this period, little ships hugged the coast of Italy delivering cargo. They could be compared to today’s UPS trucks. The Italians made the most beautiful ships 1,000 years ago as their country was a center for art, design, and engineering.

Both the Gotland and the Gokstad are in the Viking Ship Museum in Oslo, Norway. The Gotland, dating from 1225, was the first to have a stern rudder The stern’s decorative ends and posts were removable so that dragon head carvings could be placed there during wartime. The carving has a split hull combining a bottom of ebony with a top of ivory.

The Goksrad was another Viking ship. It was constructed almost entirely of oak in 890 A.D. In 1881, it was found to be in remarkably good condition when discovered in a king’s burial mound in Gotland, Norway. A replica of it, made in 1893, crossed the Atlantic in 28 days.

A third ship in this room is the Oseberg. Built in 820 A.D., it was a pleasure craft used by a Viking Queen during her lifetime as a yacht for local excursions. It became a burial chamber for the queen and her handmaid in 834 A.D.. The ship was discovered in 1904, incredibly well preserved. Currently, it is in the Viking Ship Museum in Oslo.

The Valkyrie was 92 feet. It sailed out of Denmark as an armed merchant ship without cannon in 1370. Her men had bows and arrows, crossbows, and lances to ward off pirates. In time of war, a ship such as this would be required for state service of the merchant who owned her. The dragon on the figurehead and multi-colored designs on the castles indicate this ship was armed. The name Valykrie comes from Norse mythology.

The Loessi, an elegant merchant ship, sailed from Genoa in 1370 A.D. According to David, it represents the epitome of medieval ship building and design. He said that its fine lines and elegant features were seldom seen in other ships from the same time period. For example, it had glass windows, which were very rare, on the cabin’s front.

AGE OF EXPLORATION

The Spanish and Portuguese during the 1400's built ships with multiple masts and stronger hulls as they hoped to reach India and China. The Mataro ship was an early design in this effort. It was followed by the Caravels of the Nina and Pinta and the Naos like the Santa Maria.

During this period, all of the tourist business from Northern Europe to the Mediterranean was church related. The argument was where the wealthy should go next summer. The most popular locale was Jerusalem, followed by Rome, then St. James Burial Place in northern Spain.

Pilgrims chartered ships for the New World which were deadheaded one way. Ships like the Mayflower sailed back empty. The Susan Constant, the largest of three ships which went to Virginia, was a one way ticket for passengers headed for Jamestown but brought back precious minerals to England. The actual ship’s decoration on the hull’s exteriors were painted on. David has recreated them by scrimshawing them.

Vasco da Gama sailed on the Sao Gabriel from Portugal on a two-year journey to India in 1497. He was the first to link Europe and Asia by an ocean route connecting the west with the orient. This opened the way for global discovery and trade among many people.

David’s collection also includes Columbus’s three ships, Hudson’s Half Moon, Captain Cook’s Endeavor, Drake’s Golden Hinde, the H.M.S. Bounty, and the Mayflower.

THE MODERN SHIPS

It’s on David’s showcase of modern ships, more than his other carvings of earlier eras, that his elegant ivory rigging lines are more evident. At the diameter of the thickness of only two human hairs, ivory will bend enough to give him the curved lines he desires in each carving’s superstructure.

One of his carvings is of the U.S.S. Constitution, one of six heavy frigates authorized in 1794 to form the U.S. Navy. She had a 57 year career before retiring as a U.S. Naval training ship. She is the oldest commissioned ship in the Navy. Residing today in Boston Harbor, she is open to the public.

Another is of the Niagara, the relief flagship that Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry captained during the Battle of Lake Erie on September 10, 1813 during the War of 1812. She was one of the nine ships that defeated a British squadron of six vessels. The victory secured the Northwest Territory and lifted the nation’s morale. Her cannon barrels were cast in Pittsburgh while the ship was built near Erie, Pennsylvania.

HERITAGE ROOM

Maryruth, David’s wife, gave us a tour of the Heritage Room which honors David’s grandfather, Mooney Warther. You can see one of the five steel mills Mooney made and a photo of him and his brother at the mill.

It also contains some of the commando knives David’s father made and some kitchen cutlery. The cane is a replica of the one Mooney made for Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

The room houses David’s early ships which his mother kept. He used matchsticks and toothpicks instead of ivory for rigging on these. You can also view the Corsair he made after crafting his first ship.

DETAILS

You will find this 10,000 square foot museum between the villages of Sugarcreek and Walnut Creek, Ohio at 1775 State Route 39. The telephone number is (330) 852-6096. Admission is $10 for adults; $5 for ages 5-18, and free for under age 5. Hours from April through October are Monday through Saturday 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. They are open during the winter from 10:00 a.m. to 4:00 Thursday through Saturday. Closed year round on Sunday. Visit David's web site to see even more carvings.

David Warther Museum

David Carving a Piece

David Doing Scrimshaw

Natural History Display of Various Types of Ivory

Third Largest Pair of Elephant Tusks in the United States

The First Ship David Carved

A Corsair, The First Airplane David Carved

Royal Ship of Pharaoh Cheops, His Own Personal Luxury Yacht

Fifth Dynasty Traveling Ship. an Early Egyptian Passenger Ship

Eye of the Sun, a Fifth Dynasty Cargo Ship

Huntress of Aherns, a 120 Foot Warship from 330 B.C.

Gokstad, a Viking Ship Found in the Viking Museum in Oslo

Gotland, Another Viking Ship Found in the Viking Ship Museum in Oslo

Oseberg, A Pleasure Craft Used by a Viking Queen Then Later a Burial Chamber

Mayflower

Susan Constant, Essential in Bringing People to Jamestown

Columbus's Three Ships

Sao Gabriel, Vasco da Gama's Ship From Portugal to India

U.S.S. Constitution, One of Six Frigates in 1794 That Became the U.S. Navy