Hello Everyone,

U.S. Highway 101 runs from Mexico to Canada including Oregon’s 400 mile coast. Because of this highway, throngs of visitors easily travel there to the Coast each year. As you drive this route, you can stop at overlooks with outstanding scenery, pass over beautiful bridges, and, journey through seaside towns, each with their own personality. This wasn’t always the case.

HISTORY OF OREGON COAST HIGHWAY

The area’s first residents, the Alsea Indians, used canoes to travel across the bays and estuaries. Settlers used muddy wagon trails or beaches to accommodate stagecoaches and wagons or traveled by train. They used ferries as their means of water transportation. Communities remained isolated from each other, and travel was not easy.

The use of river barges and scows grew in the 1890s, and by 1900 wagons gave way to automobiles. The number of automobiles grew tremendously in a short period of time. For example, in 1916, Waldport had three autos, but by 1930, they were commonplace. Roads were “planked” with wood, crushed rock, or shell material to make them passable. Often, the beach was still the only north-to-south route.

Ferries were still used. In 1920, Waldport had two. This sometimes resulted in passengers waiting three to four hours to cross. A public clamor arose for bridges and highway access to the Oregon Coast.

On March 4, 1933, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt called for an ambitious public works relief program to rescue the economy. At that time, Oregon had a highly regarded engineer, Conde B. McCullough, who was serving as bridge engineer for the Oregon State Highway Department (OSHD). Because of his reputation and his close personal ties with the director of the U.S. Bureau of Public Roads, Oregon obtained the resources to complete U.S. Highway 101 by 1936.

McCullough was born in the South Dakota Territory in 1887 and moved to Iowa as a small boy. His experience with a job on the section gang, maintaining portions of the Illinois Central Railroad’s track, led to his interest in engineering. He graduated from Iowa State College in 1910 and went to work for the Marsh Bridge Company. A year later, he joined the Iowa State Highway Commission (ISHC). McCullough drafted plans for small bridges and culverts for use in Iowa’s counties with the state becoming a leader in road development.

During the early days of road and bridge construction, it was common for corrupt and incompetent construction companies to build substandard bridges, roads, and culverts. The situation was so prevalent that it became scandalous. In 1913, the Iowa Legislature, to overcome this situation, required its counties to follow road and bridge designs prepared by the ISHC.

In 1916, McCullough became an assistant professor of civil engineering and sole structural engineering professor at what is now Oregon State University. He stayed on the faculty for only three years. In 1919, he became the state bridge engineer for the Oregon State Highway Department (OSHD).

His first priorities, in building the state’s major highways, were completing the Pacific Highway, which connected Oregon with Washington and California, and the Columbia River Highway.

Ben Jones was a leader of the lobbying effort to build a highway on the Oregon Coast. In 1919, as an Oregon State Representative, he wrote the first bill authorizing the construction of the Oregon Coast Highway. It was also known as the Oregon Roosevelt Coast Military Highway Act.

The measure appropriated $2,500,000, contingent upon a similar amount paid by the federal government, to construct a military highway from Astoria, Oregon to the California border. The $2,500,000 was to be paid for with bonds. Oregonians passed the measure by a 2-1 vote. Matching federal funds failed to materialize.

When construction began in 1921, only a handful of segments of north-to-south aligned roads existed. Coos Bay was connected to Crescent City in Northern California. In the north, another road, created in 1914, linked Tillamook to Astoria. Hardly any roads ran north to south on the Central Coast. Funding had been a serious problem.

Major challenges were the two tunnels on U.S. Highway 101 at Arch Cape and Heceta Head. It took more time than expected to prepare for the tunnel site because basalt at Arch Cape and the other headlands fractured easily. Millions of years ago, when the lava cooled, it cooled rapidly which made these basalt formations more brittle than other basalt formations. It was hard to calibrate how much explosives to use since overuse often fractured the rocks even more.

McCullough and his staff designed and built 600 bridges in his first six years at OSHD. Most of these were short reinforced-concrete spans that crossed smaller streams. By tackling the smaller streams first, it led the OSHD to stitch together miles of paved roads.

His first significant bridge was the Old Young’s Bay Bridge, a mile-and-a-half south of Astoria, completed in 1921. His second bridge, finished in 1924, crossed the Lewis & Clark River, a short distance west of Old Young’s Bay Bridge. This allowed automobiles to access beach resorts on the Northern Oregon Coast.

Next McCullough completed bridges at Depoe Bay, Rocky Creek in Lincoln County, and Soapstone Creek. The bridge at Rocky Creek was renamed the Ben Jones Memorial Bridge after Ben Jones, who died in 1925 of a heart attack. His Wilson River Bridge near Tillamook, finished in 1931, was the first reinforced-concrete, tied arch span constructed in the United States.

Working with the Federal Bureau of Public Roads, McCullough continued to design and construct bridges along the Coast. One of these was the Cape Creek Bridge, 12 miles north of Florence. The federal government paid for two thirds of that one. Completed in 1932, it was a 619-foot long, two-tiered, reinforced-concrete, arched structure. McCullough had always been favorable to European architectural influences. The famous Roman Aqueduct near Nimes, France was his influence on this bridge.

In 1927, the State of Oregon took over the private services that ferried cars and people across major river/estuary crossings on the Oregon Coast. These were at Gold Beach, North Bend/Coos Bay, Reedsport, Florence, Waldport, and Newport. The state-operated ferries ran nonstop for 16 hours a day, carrying from eight to 32 cars per crossing. However, the service could be time consuming and unpredictable. It became obvious that these six areas had to be spanned with bridges.

The Isaac Patterson Bridge, located on the Rogue River, was constructed first for two reasons: Rogue River conditions made the ferry crossing unreliable and the bridge would attract California visitors. When finished in August 1931, it was 1,898 feet long with a series of seven reinforced-concrete arches.

It was the first bridge in the United States to utilize the Freyssinet method of arch decentering (precompression) and stress adjustment of arch ribs. The method, introduced by French engineer Eugene Freyssinet, reduced the size of arch ribs, needing less concrete and reinforcing steel to construct the bridge. Freyssinet's method was instrumental in the development of the widespread use of prestressing techniques in concrete construction today.

McCullough and his staff designed the five other bridges in three months. One bridge, the Yaquina Bay Bridge in Newport, presented a major challenge. Swift currents required a continuous 100-hour pour of 2,200 yards of concrete. When the pour began, it continued for 24 hours a day, no matter what the weather conditions were.

Controversy developed when timber companies lobbied to have the coastal bridges made out of wood. McCullough prevailed and the five bridges were constructed of steel and concrete. However, large amounts of lumber were used to build the scaffolding and concrete forms needed to build the bridges.

Work was heavily labor intensive. Hundreds of people were put to work. Among those were members of the Civilian Conservation Corps who did stonework at a number of places such as Cape Perpetua and Heceta Head/Sea Lion Caves.

Finally, on September 6, 1936, the last of the six great coastal bridges, the Yaquina Bay Bridge, was opened to traffic. It was the last link of the Oregon Coast Highway. The total cost of the five coastal bridges built between 1933 and 1936 was $6 million. The total cost of building U.S. Highway 101 was $25 million. It took fifteen years to construct.

The round Romanesque arch remained a constant theme in McCullough’s bridges. But other architectural elements were present as well. In his five last bridges, he turned to Gothic themes for bridge approaches, the railings, and other components. At the Yaquina Bay Bridge and the bridge in North Bend/Coos Bay, one sees towering Gothic (pointed, vertical) arches for the main piers. The cantilevered steel structure of the Coos Bay/North Bend Bridge closely mirrors Portland’s Gothic style St. John’s Bridge which he deeply admired.

McCullough also wove Art Deco designs into all six major coastal bridges. The most celebrated Art Deco design was the sunburst crown of New York City’s Chrysler Building, which he used frequently on pylons, obelisks, piers, and flat surfaces.

McCullough didn’t just build beautiful bridges on the Coast. He built them all over Oregon. He also took a leave of absence in 1936 from OSHD to spend 17 months in Central America to build bridges for the Pan American Highway. His goal was to always combine function with form and grace.

Upon his return in 1937, he learned his job of bridge engineer had been given to his subordinate. He became an administrator which did not please him. He clashed with his superior, Robert Baldcock, when the idea of steel-reinforced concrete construction techniques, which McCullough and others pioneered, led to a new idea in bridge construction design - pre-stressed reinforced-concrete girder spans.

Denied from designing bridges during the last ten years of his career, McCullough wrote books on engineering. He also participated in developing a master plan for Salem, Oregon which changed the face of Oregon’s Capitol city. He died of a massive stroke on May 5, 1946. On August 27, 1947, McCullough’s favorite structure, the bridge in North Bend/Coos Bay, was renamed the Conde B. McCullough Memorial Bridge.

Only one of his major coastal bridges, the Alsea Bay Bridge, had to be destroyed and replaced with a new structure. The first bridge, constructed in 1936, was 3,011 feet long, It had a reinforced-concrete combination deck and through arches. Years of irreversible corrosion to the steel reinforcements, brought on by the Pacific coastal environment of rain, wind, and salt, led to its demolishment in 1991. A new one was completed the same year.

The second bridge at the site is 2,910 feet long with a 450-foot main space. It has a latex concrete deck and thicker than normal piers to try and thwart corrosion. Its life expectancy is 75 to 100 years. It has his signature - a large graceful arch. A viewing area at the bridge’s south end displays several of the original Art Deco pylons, spires, and railings from the original bridge

ALSEA BAY HISTORIC INTERPRETATIVE CENTER

A stop at Waldport’s Alsea Bay Historic Interpretative Center teaches visitors, via a time line all around one room, a lesson about Waldport and the state’s transportation history. It also has displays celebrating McCullough and information on the many bridges he built. Among the exhibits are an extensive model of the Alsea Bay Bridge, photos of the bridge’s construction, and a map of Oregon bridges exceeding 500 feet long. In a play area, children can build bridges.

The center was built in 1991 by the Oregon Department of Transportation, as part of the new bridge construction project, to memorialize the original 1936 bridge. If you visit, be sure to ask staff to play the 20-minute video about the bridge’s demolition and replacement.

Operated by the Oregon Parks and Recreation Department, the center shares space with Waldport Chamber of Commerce so it’s a great place to get brochures and ask questions about the area and the whole Coast. During the summer, bridge tours, led by a park naturalist, take place at 2:00 p.m. The tour covers the story of the bridge’s replacement. Guides from the department also lead clamming and crabbing demonstrations during the visitor season. Locations and times vary with the tides. Check the schedule usually posted at the interpretative center.

The interpretative center is located at the south end of the bridge. Admission is free. Summer hours are 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. daily. It is closed during the winter season on Sundays and Mondays. The telephone number is (541) 563-2002. The address is 320 NW Pacific Coast Highway in Waldport.

MORE ON YAQUINA BAY BRIDGE

Having spent ten days based in Newport, we frequently traveled over the Yaquina Bay Bridge, whose completion in 1936 meant the construction of U.S. Highway 101 was over. It spans Yaquina Bay south of Newport. Approximately 220 men were employed to construct the bridge.

It’s a combination of steel and concrete arches. The main span of the 3,223-foot structure is a 600-foot steel through arch with the two lane road penetrating the arch’s middle. It’s flanked by two identical 350-foot steel deck arches with five concrete deck arches of diminishing size extending to the south landing. The piers are supported by timber pilings driven to a depth of about 70 feet.

It uses Art Deco and Art Moderne design motifs as well as elements of Gothic architecture. Gothic influence is seen in the balustrade which features small pointed arches. A balustrade is a low wall placed at the sides of bridges made of a row of short posts topped by a long rail. Pedestrian plazas are at the bridge’s ends which allows views of the bridge. Access to the parks is at the landings by the stairways.

The bridge has become a symbol of the Oregon Coast and a favorite of photographers. An average of 16,000 vehicles cross it each day with more than 20,000 vehicles using it daily during the peak summer season. Placed on the National Register of Historic Places on August 5, 2005, it was one of eleven of McCullough’s bridges receiving that honor that year.

YACHATS’ COVERED BRIDGE

Though not a McCullough bridge, covered bridge fans might want to make a side trip at the seaside community of Yachats. At 42 feet, one of the state's shortest bridges, the Yachats Covered Bridge, is still open to vehicular traffic. Since the weight limit is eight tons and there is little turn around space, it is closed to RVs and large trucks.

Built in 1938, at a cost of $1,500, by Otis Hamer, its timber construction is of Queenpost Truss style. The bridge’s flared sides result from buttresses underneath its siding. Ribbon openings under the roof-line allow light to enter the inside at the bridge’s center. Its red color makes it different. Looking around, I was intrigued by the belted black cattle in the pasture next door. Area children call them Oreo cows for the white stripe circling their midsection.

Since the covered span is the only access for area families, the bridge roof was removed to allow a mobile home to cross in the early 1980s. The bridge was restored then rededicated to Lincoln County on December 16, 1989. Trusses and approaches were replaced and a new roof and siding added.

You can reach this bridge by driving east from Yachats seven miles on Yachats River Road. Turn left just beyond a cement bridge. Drive two miles up the north fork of Yachats River on a well maintained gravel road to come to the bridge.

CAPE PERPETUA

Run by the U.S. Forest Service, the Cape Perpetua area, two miles south of Yachats on Highway 101, has overlooks and a visitor center worthy of exploring. Its 2,700 acres are recognized as a National Scenic Area. Camping, picnicking, hiking, sightseeing, and whale watching are available.

The center is open seven days a week most of the year. Summer hours are 9:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. daily. It offers short nature and overview movies shown on demand in the theater, a bookstore, and a staff willing to answer questions. Exhibits are on the cultural history and natural aspects of the area. You can see displays on whale watching, the native people, and the area’s fish and flora. Activities are free but a valid federal recreation pass is needed for parking.

Check the schedule at the center for ranger led programs. In 2015, these took place on Saturdays and Sundays at 11:00 a.m., 1:00 p.m., and 3:00 p.m. Field rangers were in the field daily except Wednesday from June 1 to September 4. Ranger led hikes occurred on Mondays at noon. Call them at (541) 750-7000 to hear this year’s plans.

From the visitor center, take Overlook Road two miles to the top of the mountain. It’s the highest point you can drive to on the Oregon Coast. On a clear day, it’s touted that you can see 70 miles of Oregon coastline and as far as 37 miles out to sea.

You can get a panoramic ocean and headland view from near the parking lot. It’s also ideal for whale watching. But if you’re into hiking, take the half mile loop trail from the parking lot to the West Shelter viewpoint. The CCC stone masons built the shelter in the 1930s. It served as a coastal lookout point during World War II. A large coastal gun was temporarily installed there as was radar to take advantage of the promontory’s height.

Another hike is the Giant Spruce Trail (2 miles round trip). The Sitka Spruce at the end of the trail is nearly 600 years old, more than 185 feet tall, and has a 40-foot circumference. It has been designated as an Oregon Heritage Tree.

There are other hikes as well - 11 different trails for a total of 27 miles. Many of these interconnect with one another. The Captain Cook Trail, which is handicapped accessible, leads from the visitor center to skirt the shoreline.

DEVIL’S CHURN

While at Cape Perpetua, be sure to take in the misnamed Devil’s Churn which is more of a funnel than a churn. Wave action carved into the basalt shoreline of Cape Perpetua a deep chasm which likely started as a narrow fracture or collapsed lava tube. Over thousands of years of wave pounding, it’s now more than 80 feet wide where it opens at the ocean. It funnels the waves’ energy, then compresses them, constantly building pressure. This results in dramatic explosions, up to several hundred feet into the air, of sea and foam. The sight and sound resembles a whale spouting.

In many cases, the explosions come from near its mouth. You are more likely to see them during the winter and spring since the summer and fall have Devil’s Churn in a more mild mood.

You can see it well from the parking lot 50 feet above the site. If you prefer and are very careful, you can take the scenic path to the parking lot’s bottom. However, it’s essential to stay away from ledges at all times. If the waves are churning, stay clear of the bottom, as this site often tosses logs and other debris into the air. During calmer moments and low tides, it’s possible to notice the crevice goes beneath the rock and then the rock face opens again. This is especially dangerous to go near since this is where much of the debris is lobbed.

For those brave enough to take the main path down to the Devil’s Churn, they’ll find a beach and some park benches. It provides views to the top of Cape Perpetua.

SPOUTING HORN AND THOR’S WELL

You can also visit the spouting horn at Cook’s Chasm. At high tides or during winter storms, this gaping sinkhole shoots waves to a height of 20 feet high. However, approaching it is dangerous since sharp rocks are everywhere and a strong water surge could suck you into the abyss.

Thor’s Well, in the nearby plateau, is another that acts like a salt water fountain. It, too, is driven by the power of the ocean’s tides. It also can be dangerous, particularly at a high tide and during winter storms.

Both are best seen approximately an hour before a high tide to an hour after a high tide. How spectacularly the waves shoot into the air is related to the height of the high tide and the direction and size of the swells.

NEPTUNE STATE SCENIC VIEWPOINT

Three miles south of Yachats, close to Cape Perpetua, visitors find a series of four viewpoints. We stopped at the northernmost which doesn’t have a name. It offers access to a small isolated beach and dramatic camera shots. Another stop, to the south, is Strawberry Hill providing excellent ocean views and a series of stairs leading down to tide pools and sandy beaches. On sunny days, you might see harbor seals enjoying themselves on the rocks just off shore. It’s also ideal for bird watching.

U.S. Highway 101 runs from Mexico to Canada including Oregon’s 400 mile coast. Because of this highway, throngs of visitors easily travel there to the Coast each year. As you drive this route, you can stop at overlooks with outstanding scenery, pass over beautiful bridges, and, journey through seaside towns, each with their own personality. This wasn’t always the case.

HISTORY OF OREGON COAST HIGHWAY

The area’s first residents, the Alsea Indians, used canoes to travel across the bays and estuaries. Settlers used muddy wagon trails or beaches to accommodate stagecoaches and wagons or traveled by train. They used ferries as their means of water transportation. Communities remained isolated from each other, and travel was not easy.

The use of river barges and scows grew in the 1890s, and by 1900 wagons gave way to automobiles. The number of automobiles grew tremendously in a short period of time. For example, in 1916, Waldport had three autos, but by 1930, they were commonplace. Roads were “planked” with wood, crushed rock, or shell material to make them passable. Often, the beach was still the only north-to-south route.

Ferries were still used. In 1920, Waldport had two. This sometimes resulted in passengers waiting three to four hours to cross. A public clamor arose for bridges and highway access to the Oregon Coast.

On March 4, 1933, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt called for an ambitious public works relief program to rescue the economy. At that time, Oregon had a highly regarded engineer, Conde B. McCullough, who was serving as bridge engineer for the Oregon State Highway Department (OSHD). Because of his reputation and his close personal ties with the director of the U.S. Bureau of Public Roads, Oregon obtained the resources to complete U.S. Highway 101 by 1936.

McCullough was born in the South Dakota Territory in 1887 and moved to Iowa as a small boy. His experience with a job on the section gang, maintaining portions of the Illinois Central Railroad’s track, led to his interest in engineering. He graduated from Iowa State College in 1910 and went to work for the Marsh Bridge Company. A year later, he joined the Iowa State Highway Commission (ISHC). McCullough drafted plans for small bridges and culverts for use in Iowa’s counties with the state becoming a leader in road development.

During the early days of road and bridge construction, it was common for corrupt and incompetent construction companies to build substandard bridges, roads, and culverts. The situation was so prevalent that it became scandalous. In 1913, the Iowa Legislature, to overcome this situation, required its counties to follow road and bridge designs prepared by the ISHC.

In 1916, McCullough became an assistant professor of civil engineering and sole structural engineering professor at what is now Oregon State University. He stayed on the faculty for only three years. In 1919, he became the state bridge engineer for the Oregon State Highway Department (OSHD).

His first priorities, in building the state’s major highways, were completing the Pacific Highway, which connected Oregon with Washington and California, and the Columbia River Highway.

Ben Jones was a leader of the lobbying effort to build a highway on the Oregon Coast. In 1919, as an Oregon State Representative, he wrote the first bill authorizing the construction of the Oregon Coast Highway. It was also known as the Oregon Roosevelt Coast Military Highway Act.

The measure appropriated $2,500,000, contingent upon a similar amount paid by the federal government, to construct a military highway from Astoria, Oregon to the California border. The $2,500,000 was to be paid for with bonds. Oregonians passed the measure by a 2-1 vote. Matching federal funds failed to materialize.

When construction began in 1921, only a handful of segments of north-to-south aligned roads existed. Coos Bay was connected to Crescent City in Northern California. In the north, another road, created in 1914, linked Tillamook to Astoria. Hardly any roads ran north to south on the Central Coast. Funding had been a serious problem.

Major challenges were the two tunnels on U.S. Highway 101 at Arch Cape and Heceta Head. It took more time than expected to prepare for the tunnel site because basalt at Arch Cape and the other headlands fractured easily. Millions of years ago, when the lava cooled, it cooled rapidly which made these basalt formations more brittle than other basalt formations. It was hard to calibrate how much explosives to use since overuse often fractured the rocks even more.

McCullough and his staff designed and built 600 bridges in his first six years at OSHD. Most of these were short reinforced-concrete spans that crossed smaller streams. By tackling the smaller streams first, it led the OSHD to stitch together miles of paved roads.

His first significant bridge was the Old Young’s Bay Bridge, a mile-and-a-half south of Astoria, completed in 1921. His second bridge, finished in 1924, crossed the Lewis & Clark River, a short distance west of Old Young’s Bay Bridge. This allowed automobiles to access beach resorts on the Northern Oregon Coast.

Next McCullough completed bridges at Depoe Bay, Rocky Creek in Lincoln County, and Soapstone Creek. The bridge at Rocky Creek was renamed the Ben Jones Memorial Bridge after Ben Jones, who died in 1925 of a heart attack. His Wilson River Bridge near Tillamook, finished in 1931, was the first reinforced-concrete, tied arch span constructed in the United States.

Working with the Federal Bureau of Public Roads, McCullough continued to design and construct bridges along the Coast. One of these was the Cape Creek Bridge, 12 miles north of Florence. The federal government paid for two thirds of that one. Completed in 1932, it was a 619-foot long, two-tiered, reinforced-concrete, arched structure. McCullough had always been favorable to European architectural influences. The famous Roman Aqueduct near Nimes, France was his influence on this bridge.

In 1927, the State of Oregon took over the private services that ferried cars and people across major river/estuary crossings on the Oregon Coast. These were at Gold Beach, North Bend/Coos Bay, Reedsport, Florence, Waldport, and Newport. The state-operated ferries ran nonstop for 16 hours a day, carrying from eight to 32 cars per crossing. However, the service could be time consuming and unpredictable. It became obvious that these six areas had to be spanned with bridges.

The Isaac Patterson Bridge, located on the Rogue River, was constructed first for two reasons: Rogue River conditions made the ferry crossing unreliable and the bridge would attract California visitors. When finished in August 1931, it was 1,898 feet long with a series of seven reinforced-concrete arches.

It was the first bridge in the United States to utilize the Freyssinet method of arch decentering (precompression) and stress adjustment of arch ribs. The method, introduced by French engineer Eugene Freyssinet, reduced the size of arch ribs, needing less concrete and reinforcing steel to construct the bridge. Freyssinet's method was instrumental in the development of the widespread use of prestressing techniques in concrete construction today.

McCullough and his staff designed the five other bridges in three months. One bridge, the Yaquina Bay Bridge in Newport, presented a major challenge. Swift currents required a continuous 100-hour pour of 2,200 yards of concrete. When the pour began, it continued for 24 hours a day, no matter what the weather conditions were.

Controversy developed when timber companies lobbied to have the coastal bridges made out of wood. McCullough prevailed and the five bridges were constructed of steel and concrete. However, large amounts of lumber were used to build the scaffolding and concrete forms needed to build the bridges.

Work was heavily labor intensive. Hundreds of people were put to work. Among those were members of the Civilian Conservation Corps who did stonework at a number of places such as Cape Perpetua and Heceta Head/Sea Lion Caves.

Finally, on September 6, 1936, the last of the six great coastal bridges, the Yaquina Bay Bridge, was opened to traffic. It was the last link of the Oregon Coast Highway. The total cost of the five coastal bridges built between 1933 and 1936 was $6 million. The total cost of building U.S. Highway 101 was $25 million. It took fifteen years to construct.

The round Romanesque arch remained a constant theme in McCullough’s bridges. But other architectural elements were present as well. In his five last bridges, he turned to Gothic themes for bridge approaches, the railings, and other components. At the Yaquina Bay Bridge and the bridge in North Bend/Coos Bay, one sees towering Gothic (pointed, vertical) arches for the main piers. The cantilevered steel structure of the Coos Bay/North Bend Bridge closely mirrors Portland’s Gothic style St. John’s Bridge which he deeply admired.

McCullough also wove Art Deco designs into all six major coastal bridges. The most celebrated Art Deco design was the sunburst crown of New York City’s Chrysler Building, which he used frequently on pylons, obelisks, piers, and flat surfaces.

McCullough didn’t just build beautiful bridges on the Coast. He built them all over Oregon. He also took a leave of absence in 1936 from OSHD to spend 17 months in Central America to build bridges for the Pan American Highway. His goal was to always combine function with form and grace.

Upon his return in 1937, he learned his job of bridge engineer had been given to his subordinate. He became an administrator which did not please him. He clashed with his superior, Robert Baldcock, when the idea of steel-reinforced concrete construction techniques, which McCullough and others pioneered, led to a new idea in bridge construction design - pre-stressed reinforced-concrete girder spans.

Denied from designing bridges during the last ten years of his career, McCullough wrote books on engineering. He also participated in developing a master plan for Salem, Oregon which changed the face of Oregon’s Capitol city. He died of a massive stroke on May 5, 1946. On August 27, 1947, McCullough’s favorite structure, the bridge in North Bend/Coos Bay, was renamed the Conde B. McCullough Memorial Bridge.

Only one of his major coastal bridges, the Alsea Bay Bridge, had to be destroyed and replaced with a new structure. The first bridge, constructed in 1936, was 3,011 feet long, It had a reinforced-concrete combination deck and through arches. Years of irreversible corrosion to the steel reinforcements, brought on by the Pacific coastal environment of rain, wind, and salt, led to its demolishment in 1991. A new one was completed the same year.

The second bridge at the site is 2,910 feet long with a 450-foot main space. It has a latex concrete deck and thicker than normal piers to try and thwart corrosion. Its life expectancy is 75 to 100 years. It has his signature - a large graceful arch. A viewing area at the bridge’s south end displays several of the original Art Deco pylons, spires, and railings from the original bridge

ALSEA BAY HISTORIC INTERPRETATIVE CENTER

A stop at Waldport’s Alsea Bay Historic Interpretative Center teaches visitors, via a time line all around one room, a lesson about Waldport and the state’s transportation history. It also has displays celebrating McCullough and information on the many bridges he built. Among the exhibits are an extensive model of the Alsea Bay Bridge, photos of the bridge’s construction, and a map of Oregon bridges exceeding 500 feet long. In a play area, children can build bridges.

The center was built in 1991 by the Oregon Department of Transportation, as part of the new bridge construction project, to memorialize the original 1936 bridge. If you visit, be sure to ask staff to play the 20-minute video about the bridge’s demolition and replacement.

Operated by the Oregon Parks and Recreation Department, the center shares space with Waldport Chamber of Commerce so it’s a great place to get brochures and ask questions about the area and the whole Coast. During the summer, bridge tours, led by a park naturalist, take place at 2:00 p.m. The tour covers the story of the bridge’s replacement. Guides from the department also lead clamming and crabbing demonstrations during the visitor season. Locations and times vary with the tides. Check the schedule usually posted at the interpretative center.

The interpretative center is located at the south end of the bridge. Admission is free. Summer hours are 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. daily. It is closed during the winter season on Sundays and Mondays. The telephone number is (541) 563-2002. The address is 320 NW Pacific Coast Highway in Waldport.

MORE ON YAQUINA BAY BRIDGE

Having spent ten days based in Newport, we frequently traveled over the Yaquina Bay Bridge, whose completion in 1936 meant the construction of U.S. Highway 101 was over. It spans Yaquina Bay south of Newport. Approximately 220 men were employed to construct the bridge.

It’s a combination of steel and concrete arches. The main span of the 3,223-foot structure is a 600-foot steel through arch with the two lane road penetrating the arch’s middle. It’s flanked by two identical 350-foot steel deck arches with five concrete deck arches of diminishing size extending to the south landing. The piers are supported by timber pilings driven to a depth of about 70 feet.

It uses Art Deco and Art Moderne design motifs as well as elements of Gothic architecture. Gothic influence is seen in the balustrade which features small pointed arches. A balustrade is a low wall placed at the sides of bridges made of a row of short posts topped by a long rail. Pedestrian plazas are at the bridge’s ends which allows views of the bridge. Access to the parks is at the landings by the stairways.

The bridge has become a symbol of the Oregon Coast and a favorite of photographers. An average of 16,000 vehicles cross it each day with more than 20,000 vehicles using it daily during the peak summer season. Placed on the National Register of Historic Places on August 5, 2005, it was one of eleven of McCullough’s bridges receiving that honor that year.

YACHATS’ COVERED BRIDGE

Though not a McCullough bridge, covered bridge fans might want to make a side trip at the seaside community of Yachats. At 42 feet, one of the state's shortest bridges, the Yachats Covered Bridge, is still open to vehicular traffic. Since the weight limit is eight tons and there is little turn around space, it is closed to RVs and large trucks.

Built in 1938, at a cost of $1,500, by Otis Hamer, its timber construction is of Queenpost Truss style. The bridge’s flared sides result from buttresses underneath its siding. Ribbon openings under the roof-line allow light to enter the inside at the bridge’s center. Its red color makes it different. Looking around, I was intrigued by the belted black cattle in the pasture next door. Area children call them Oreo cows for the white stripe circling their midsection.

Since the covered span is the only access for area families, the bridge roof was removed to allow a mobile home to cross in the early 1980s. The bridge was restored then rededicated to Lincoln County on December 16, 1989. Trusses and approaches were replaced and a new roof and siding added.

You can reach this bridge by driving east from Yachats seven miles on Yachats River Road. Turn left just beyond a cement bridge. Drive two miles up the north fork of Yachats River on a well maintained gravel road to come to the bridge.

CAPE PERPETUA

Run by the U.S. Forest Service, the Cape Perpetua area, two miles south of Yachats on Highway 101, has overlooks and a visitor center worthy of exploring. Its 2,700 acres are recognized as a National Scenic Area. Camping, picnicking, hiking, sightseeing, and whale watching are available.

The center is open seven days a week most of the year. Summer hours are 9:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. daily. It offers short nature and overview movies shown on demand in the theater, a bookstore, and a staff willing to answer questions. Exhibits are on the cultural history and natural aspects of the area. You can see displays on whale watching, the native people, and the area’s fish and flora. Activities are free but a valid federal recreation pass is needed for parking.

Check the schedule at the center for ranger led programs. In 2015, these took place on Saturdays and Sundays at 11:00 a.m., 1:00 p.m., and 3:00 p.m. Field rangers were in the field daily except Wednesday from June 1 to September 4. Ranger led hikes occurred on Mondays at noon. Call them at (541) 750-7000 to hear this year’s plans.

From the visitor center, take Overlook Road two miles to the top of the mountain. It’s the highest point you can drive to on the Oregon Coast. On a clear day, it’s touted that you can see 70 miles of Oregon coastline and as far as 37 miles out to sea.

You can get a panoramic ocean and headland view from near the parking lot. It’s also ideal for whale watching. But if you’re into hiking, take the half mile loop trail from the parking lot to the West Shelter viewpoint. The CCC stone masons built the shelter in the 1930s. It served as a coastal lookout point during World War II. A large coastal gun was temporarily installed there as was radar to take advantage of the promontory’s height.

Another hike is the Giant Spruce Trail (2 miles round trip). The Sitka Spruce at the end of the trail is nearly 600 years old, more than 185 feet tall, and has a 40-foot circumference. It has been designated as an Oregon Heritage Tree.

There are other hikes as well - 11 different trails for a total of 27 miles. Many of these interconnect with one another. The Captain Cook Trail, which is handicapped accessible, leads from the visitor center to skirt the shoreline.

DEVIL’S CHURN

While at Cape Perpetua, be sure to take in the misnamed Devil’s Churn which is more of a funnel than a churn. Wave action carved into the basalt shoreline of Cape Perpetua a deep chasm which likely started as a narrow fracture or collapsed lava tube. Over thousands of years of wave pounding, it’s now more than 80 feet wide where it opens at the ocean. It funnels the waves’ energy, then compresses them, constantly building pressure. This results in dramatic explosions, up to several hundred feet into the air, of sea and foam. The sight and sound resembles a whale spouting.

In many cases, the explosions come from near its mouth. You are more likely to see them during the winter and spring since the summer and fall have Devil’s Churn in a more mild mood.

You can see it well from the parking lot 50 feet above the site. If you prefer and are very careful, you can take the scenic path to the parking lot’s bottom. However, it’s essential to stay away from ledges at all times. If the waves are churning, stay clear of the bottom, as this site often tosses logs and other debris into the air. During calmer moments and low tides, it’s possible to notice the crevice goes beneath the rock and then the rock face opens again. This is especially dangerous to go near since this is where much of the debris is lobbed.

For those brave enough to take the main path down to the Devil’s Churn, they’ll find a beach and some park benches. It provides views to the top of Cape Perpetua.

SPOUTING HORN AND THOR’S WELL

You can also visit the spouting horn at Cook’s Chasm. At high tides or during winter storms, this gaping sinkhole shoots waves to a height of 20 feet high. However, approaching it is dangerous since sharp rocks are everywhere and a strong water surge could suck you into the abyss.

Thor’s Well, in the nearby plateau, is another that acts like a salt water fountain. It, too, is driven by the power of the ocean’s tides. It also can be dangerous, particularly at a high tide and during winter storms.

Both are best seen approximately an hour before a high tide to an hour after a high tide. How spectacularly the waves shoot into the air is related to the height of the high tide and the direction and size of the swells.

NEPTUNE STATE SCENIC VIEWPOINT

Three miles south of Yachats, close to Cape Perpetua, visitors find a series of four viewpoints. We stopped at the northernmost which doesn’t have a name. It offers access to a small isolated beach and dramatic camera shots. Another stop, to the south, is Strawberry Hill providing excellent ocean views and a series of stairs leading down to tide pools and sandy beaches. On sunny days, you might see harbor seals enjoying themselves on the rocks just off shore. It’s also ideal for bird watching.

New Alsea Bay Bridge

Art Deco Pylons, Spires, and Railings from Old Alsea Bay Bridge

McCullough's Use of the Chrysler Building Design

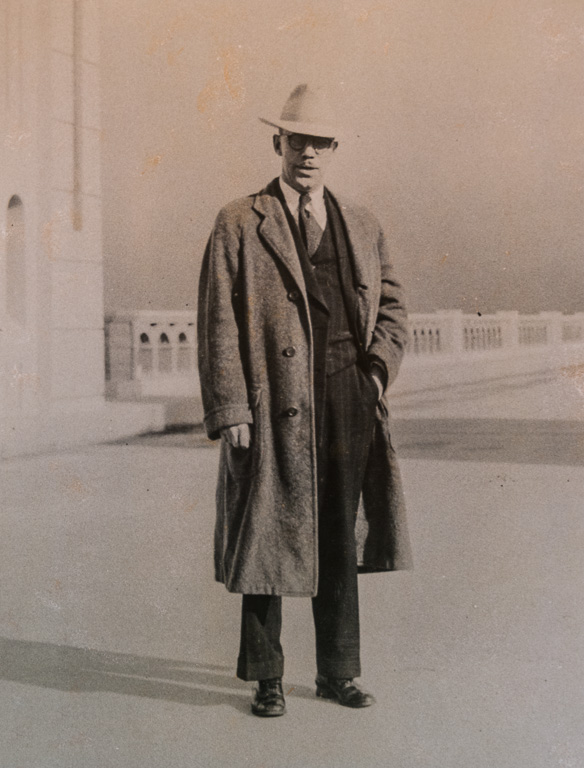

Photograph of Conde B. McCullough in Alsea Bay Historic Interpretative Center

Yaquina Bay Bridge

Another View of Yaquina Bay Bridge

Yachat's Covered Bridge

Highway 101 Crossing Cook's Chasm Near Cape Perpetua

Visitor Center at Cape Perpetua

Highway 101 From Atop the Mountain at Cape Perpetua

Ocean off Cape Perpetua

Another View of Ocean off Cape Perpetua

Devil's Churn at Cape Perpetua

Spouting Horn at Cape Perpetua

Neptune State Scenic Viewpoint

Strawberry Hill at Neptune State Scenic Viewpoint